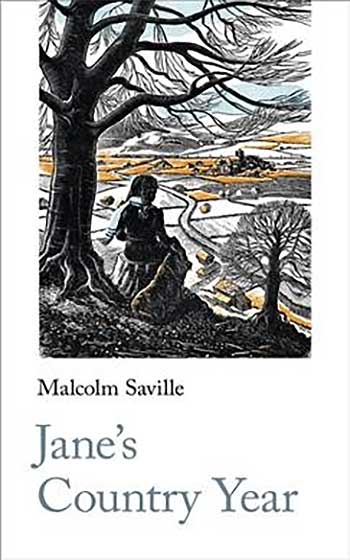

Jane’s Country Year, Malcolm Saville (Handheld Press)

Malcolm Saville’s Lone Pine Five books were part of my growing up, a more literate successor (along with Arthur Ransome’s Swallows & Amazons books) to Enid Blyton’s Famous Five books, which I loved but raced through. Saville never got much recognition for his writing for children, and only recently did I discover the Lone Pine Five paperbacks I collected (and still have) often had a quarter or more of the story removed since their initial hardback publications.

There are several publishers in recent years who have been reprinting out-of-print children’s books, marketing them to nostalgic adults keen to revisit their past, but Handheld Press – who are new to me – are not one of these. Until now they have been reissuing books by the likes of Rose Macaulay, John Buchan, Sylvia Townsend Warner and other authors I have never heard of. But their ‘Handheld Classic 24’ is this stand-alone novel-cum-nature book by Saville.

It’s a beautiful edition, with reproductions of the original illustrations included, and a new foreword contextualising the 1946 story for 21st Century readers. Hazel Sheeky Bird makes links between Saville and the likes of Blyton, notes his critical neglect, but also details how important the likes of Richard Jefferies’ book Bevis was to Saville.

Organised into twelve chapters, one for each month of the year, Jane is sent to recuperate on her uncle’s farm after a long illness in the city. There, she not only becomes well but is introduced to nature, farming, and country life, making new friends and gaining information as she goes. From the first few pages on there is a sense of wonder at the open spaces, the weather, and how people live. Her inquisitiveness is informed by her new friends, the shepherd, the farm labourer – who she at first thinks is a tramp, and the Parson’s family, not to mention her aunt and uncle.

Some of these ‘information drops’ are a little awkward, but they are redeemed by the knowledge a reader gains, and the overall narrative arc; and Bird notes that explanatory notes which were added to later editions have been removed for this edition, which returns the book to its original form. The other slight problem is the sometimes condescending and clichéd description of villagers and workers as plain simple folk, somehow more honest, open and true than the city or town folk who live where Jane and her parents live.

It is also an era where farmers were farmers, not industrial livestock or vegetable producers. Jane’s uncle keeps sheep, grows vegetables, and milks and slaughters his cattle; although he goes to market, works hard and works his employees hard, the focus of his work is what his land can produce to sustain his family and those who work on it, whilst looking after his fields and animals.

Saville did not write this novel as a polemic though, he wanted to tell a story that engaged his readers, and saw the lead character Jane, get well, mature, and learn. The pace is varied as suits the changing seasons, with some wonderful set scenes around events such as first lambing, harvest, the local fair and Christmas, various interactions with other people, and a number of epistolic sections which reproduce Jane’s letters to her (rather distant) parents. The pace is gentle and meandering, the story fairly simple, but Saville sustains the mood of engagement and wonder throughout. The pictures are a genuine bonus, and I greatly enjoyed learning about the recent historical past, however romanticised, and sharing the delight of Jane’s year in the country.

Rupert Loydell

(This review was first published at Tears in the Fence.)