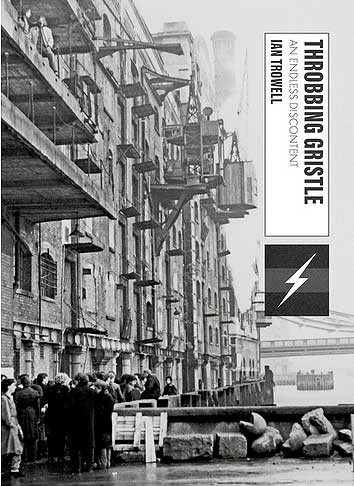

Throbbing Gristle. An Endless Discontent, Ian Trowell (Intellect)

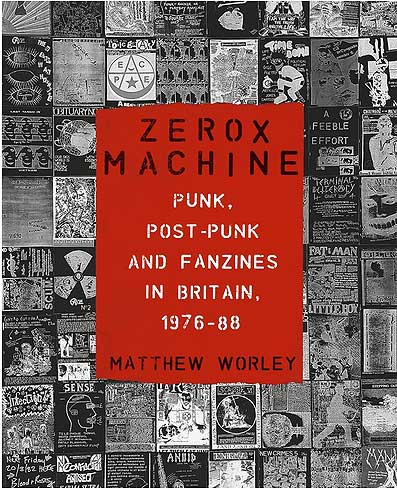

Zerox Machine. Punk, Post-Punk and Fanzines in Britain 1976-88, Matthew Worley (Reaktion)

Neu Klang. The Definitive History of Krautrock, Christopher Dallach (Faber)

Ian Trowell’s book is a marvellous trawl through the alternative and underground music of the late 1970s and early 80s, hung on the story of Throbbing Gristle; more specifically, a number of their live concerts, or performance events, around the UK. It charts their emergence from the art activism of COUM to their demise and aftermath of influence and imitation.

I never had much time for Throbbing Gristle. They were purveyors of easy outrage, recycling long established tropes of noise and improvisation from contemporary classical and avant-garde jazz* with the addition of home-made synthesizers, all framed as explorations of human sexuality, desire, evil and corruption. They set out to shock and pressed all the easy buttons, often pre-empting any genuine response by bullshitting about how provocative they were, what they thought about their own work, and how outraged previous audiences had been.

So we got recycled Charles Manson, Jim Jones, Ian Brady and Myra Hindley images and recordings, bodily fluids, blood, castration, piercings and a lot of freeform rhythmic noise, sometimes with ranting, shouting and screaming over it, all carefully recorded, documented and then sold in limited editions to those fascinated with the so-called extremes of music and human perversion.

Trowell is clearly almost as suspicious about the band’s (particularly Genesis P-Orridge’s) self-aggrandizement as I am but fails to do more than gently insinuate that not all their own recollections and version of history may be based in fact; in a similar manner he also allows much of Malcolm McLaren’s version of things to stand without questioning the hindsight he used to pretend everything he was involved in was all pre-meditated and planned.

So why do I say this book is marvellous? Well, for the way it genuinely captures the time it describes (although it is prone to using that cliché ‘the winter of discontent’ a lot) and for how Trowell uses the different locations of the TG gigs – London, Wakefield, Derby, Sheffield and others – to explore what was going on around the UK, recognising that whilst punk may have expired in London, it was only just happening elsewhere; also, that many different kinds of what we call post-punk were happening.

Throbbing Gristle of course, quickly distanced themselves from any punk flirtations they may have indulged in and, in a similar manner, would only ally themselves with a select few other bands, mostly Cabaret Voltaire, Clock DVA and 23 Skidoo. They wanted nothing to do with the likes of first incarnation Human League, who were just as intriguing as them, and made better use of synthesizers and visuals, let alone bands such as Magazine and Simple Minds who made intriguing post-punk experimental songs. In a similar manner, both Siouxsie and the Banshees and Public Image Limited would be summarily criticised and dismissed.

Throbbing Gristle, it seems, wanted control of everything, despite questioning the very notion of power and control. Having imploded, Psychic TV would emerge to repeat the exercise: noisy gigs, self-publicity, sham outrage and clever marketing; and, again, the selling of everything they could record. The one time I saw them in Manchester they came on hours late, played some pretty basic rhythmic noise, and showed a film they claimed was shocking but was so full of static and distortion it could have been (and probably was) anything. To be honest, Ivor Cutler’s performance in the hall next door, which we snuck into whilst waiting, was far more out there than Psychic TV.

Of course, all the subversive television programmes Psychic TV promised never happened, and the band’s flirtation with sado-masochism and sexual perversion backfired when police raided the P-Orridge’s house in London and they fled to California. The video the police confiscated turned out, of course, to be a bad copy of a Derek Jarman film, and the whole operation part of the satanic abuse nonsense that was around at the time. But it allowed P-Orridge to play the martyr in exile, link up with the aging Timothy Leary, and steer the band into the acid house movement. Meanwhile, he also started The Temple ov Psychic Youth, an occult network of acolytes and fans that relished recycled (Aleister) Crowley-isms as much as recycled noise and dance music, with many adopting the anti-fashion haircut of buzzcut and mullet. (Later of course, there would be reissue after reissue and band reformations, as well as P-Orridge and his partner’s body modifiations towards multi-gendered twins/lovers.)

Although Throbbing Gristle were reviewed and interviewed in the music press of the day – Sounds, NME and Melody Maker – they were particularly adept at utilising the zines that sprang up from the mid 1970s onwards. Zerox Machine (no, I thought it was spelt Xerox too; Zerox is a bar and venue in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne) is a generous selection and accomplished contextualisation of the world of grubby photocopying, bent staples and amateur design, along with the ambitious countercultural attitudes, opinionated writing and conspiratorial claims that went with it.

On the back of cheap photocopying, whether paid for or stolen, and the slowness of the music weeklies to pick up on early punk music, not to mention the do-it-yourself attitude espoused by many bands and editors, zines were everywhere. Whether handwritten, typed, collaged or immaculately designed, someone would be at every ‘alternative’ gig selling a zine in the crowd, outside or at a pub table. Rough Trade Records – in fact alternative record shops everywhere – would have zines piled high; they were immediate, accessible, informative, cheap and hip. They would argue, provoke, declare, offer opinions, reviews and interviews, and go on to be part of the flourishing cassette culture of the time, with bands making home recordings and self-releasing their music, as well as featuring on some of the hundreds of bedroom tape label compilations.

If I sound nostalgic, I am. For the days of anyone-can-do it music, of affordable gigs, of swopping zines and tapes with others around the world, of the opportunity to hear new music in the days before the internet. Gradually, of course, zine culture moved away from music, and digital and print-on-demand printing arrived, along with home computers, changing publishing for ever, in a similar way to how CDRs and Bandcamp changed the way we seek out and listen to music today, making it both more accessible and more disposable. (Although it has also had the reverse effect of bands releasing limited edition cassettes, the rise in popularity of vinyl records, and a focus on short run arty books of fiction and poetry.)

Like Trowell, Worley is brilliant at capturing the diversity, enthusiasm and energy on show in the 12 years of zine culture he covers. Whilst there are, to me, obvious omissions, he has curated a knowing and wide-ranging selection of subject matter, including – of course – the infamous and influential Sniffin’ Glue and the paranoid art-terrorism volumes of Vague, one of my favourite publications from back in the day.

One of the musical genres I should have mentioned as existing before and influencing Throbbing Gristle was, of course, what is still known as krautrock. Neu Klang is a new addition to the many books about the genre but it doesn’t live up to its claim of being ‘the definitive history’. Oral histories, of which this is one, always feel a little bit as though an author has done the research for a book that they can’t be bothered to write; this one certainly does.

Although it gives lots of musical history, returning to post-war Germany, negotiating the effects of Nazism after WW2, discussing jazz influences and questioning the name ‘krautrock’ and the ridiculous way it was applied to just about any music coming out of Germany at the time, it is problematic. Firstly, in that the interviews appear to be contemporary, so that everyone is remembering their own versions of music, events and relationships from long ago; secondly that the apparent conversations between musicians going on are assembled by the author on the page and did not actually occur.

Having explored ‘Post-War Youth’ and ‘Jazz’ in ‘The Fifties’, Dallach creates a discussion of ‘The Sixties’, including sections on long hair, communes, the revolutionary events of 1968, drugs and the early bands Zodiak and Kluster. He then moves onto the largest chapter, ‘The Seventies’, which stretches for 250 pages. Here we get discussions about the usual suspects of Tangerine Dream, Can, Amon Düül, Faust, Kraftwerk and Neu!, along with more obscure bands, as well as opinions about ‘Commercialism’, ‘Moog’, ‘New Paths’, ‘Networks’ and ‘Beyond Germany’. It’s fascinating to see who knew who, influenced or worked with each other and the different reactions to cult status, critical reception and the terrorist politics of the Red Army Faction/Baader-Meinhof Gang.

Whilst I am not accusing those interviewed with Throbbing Gristle type manipulations of their past, the memory does play tricks and we all adapt and reversion our own stories, just as music historians and cultural studies do. Dallach does not appear to question what is said, although he sometimes allows others to appear to do so. I understand that oral histories are designed to work with original material but I’d like to have seen interview material from the 70s woven in to the book alongside the contemporary. But like Throbbing Gristle and Zerox Machine, Neu Klang captures the historical context, the excitement, the social changes happening and the musical exploration that was going on. All three are well worth a read.

Rupert Loydell

* Take a listen to classical music by Luigi Russolo, Pierre Schaeffer, Edgar Varèse, Xenakis, Stockhausen, Ligeti or Morton Subotnick; and jazz from Sun Ra, Ornette Coleman, electric Miles Davis, late John Coltrane. There are also improvising groups such as AMM and the Music Improvisation Company, and precedents in the rock world (in addition to krautrock) such as Red Krayola and possibly even early Pink Floyd, not to mention albums such as Lou Reed’s infamous Metal Machine Music in 1975. All well before Throbbing Gristle ‘invented’ noise or industrial music.

Throbbing Gristle – At the Ajanta Cinema, Derby, 1979

.

There are these too of course! https://internationaltimes.it/zerox-machine-punk-post-punk-and-fanzines-in-britain-1976-88-reaktion-books/

Comment by Alan Rider on 7 April, 2024 at 3:46 pmhttps://internationaltimes.it/the-best-worst-band-in-the-world-throbbing-gristle/