Throbbing Gristle – An Endless Discontent’ by Ian Trowell (Intellect Press). December 2023

Alan Rider reports back on ‘An Endless Discontent’, a skilful dissection of the enigma that was Throbbing Gristle.

“Tempting though it is to see TG as a proto punk band ..they, and Coum Transmissions, were a self-consciously arty project of the like punk professed to blow away, but never did”

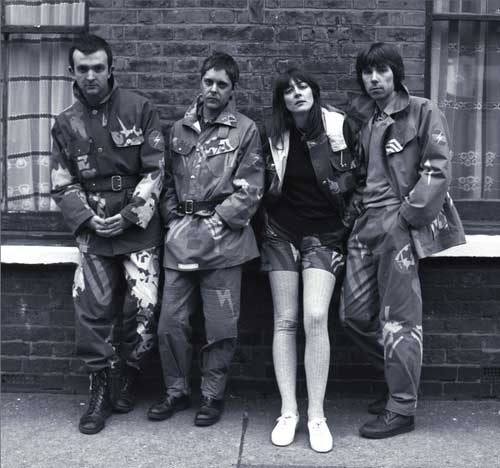

It’s true to say that, with a career that lasted roughly five years from 1977 (though when they actually formed as a unit depends on your definition of that term), existing on the edges of early punk and post-punk, and encompassed around 30 live performances, a handful of self-produced records and tapes issued on their own Industrial Records imprint, and a clutch of pamphlets, manifestos and events, Throbbing Gristle’s influence extends far beyond their short, but highly productive, existence. Over the years there have been multiple reissues and cataloguing of every performance, utterance, image, and press clipping to such an extent it is near impossible to separate myth from reality, not helped by TG agitator-in-chief Genesis P-Orridge’s tendency to exaggerate and obscure. Add to that the influence of the subsequent activities of TG members as they split and scattered into Chris and Cosey, Psychic TV and Coil (along with other multiple spin offs, side projects, and collaborations too numerous and convoluted to mention) and you have an impressive body of work that forms a lasting legacy now that two of the four members of TG have died. The history of TG has been covered many times, most impressively in Simon Ford’s 1999 book on TG and its Performance Art predecessor, Coum Transmissions, ‘Wreckers of Civilisation’, so named after a Tory MPs outraged condemnation of Coum Transmissions 1976 Prostitution show at the ICA. All of this makes Ian Towell’s task in writing a new book capturing the TG story and narrative an unenviable challenge, fraught with dangers, not least from the notoriously fussy and over sensitive body of TG fans/fanatics waiting with knives sharpened to slash away at any inaccuracy, error, or perceived slight to their heroes.

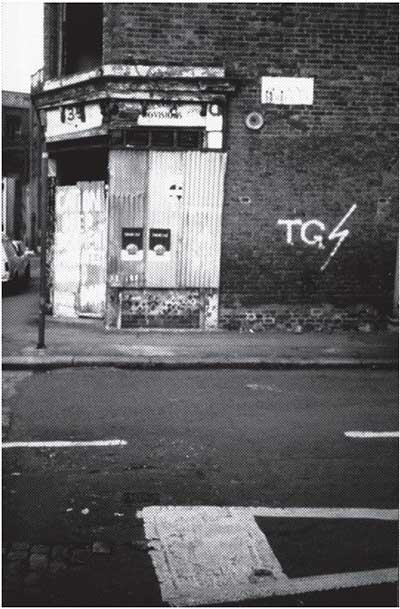

Ian is made of sterner stuff though and approaches this gargantuan task through the lens of place, describing the locations and circumstances surrounding key moments in TG’s evolution and history in order to put them into the context of the times and the geography of both their Hackney ‘Death Factory’ base and regional performances in Wakefield, Sheffield, Derby, and elsewhere, in what he describes as ‘space, place, and being there’. It’s an effective strategy and one that draws you in to the experience of Throbbing Gristle at the time and puts across the bleakness and desperation of the times, where there genuinely seemed ‘No Future’ for a whole generation and the shadow of the Cold War still loomed large. Chapters have titles like ‘Restlessness’, ‘Anti-gig’, and ‘Anachrony in the UK’ which effectively act as shorthand for the trajectory of TG’s evolution. There are sub headings such as ‘Malignant Hum’, ‘Bunker Mentality’ or ‘The World is a War Film’, all of which combine to give you a flavour of Throbbing Gristle’s confrontational stance and genre defining sloganeering. Published in conjunction with the Punk Scholars Network, a collective of like-minded intellectuals and former punks, the style of ‘An Endless Discontent’ is academic in tone, with extensive references and end notes that could have derailed the flow of the book and created a distance between the writer and his subject. Thankfully that is not the case and Ian’s style treads the fine line between an entertaining and compelling telling of the TG story and factual accuracy and scholarly rigour, albeit occasionally lapsing into somewhat impenetrable academic prose in places. Stories such as the infamous Gary Gilmore T Shirt sold by Boy, the Coum transmissions 1976 ICA show and the media reaction to that, and incursions into the Architectural Association, Wakefield College, Derby Ajanta theatre and Sheffield University are all covered in impressive detail, as are numerous press articles and gigs. The Sheffield chapter for example bookends their appearances in the City in Spring 1979 and Summer 1980 as a vehicle to describe the evolution of TG over that year, which was a pivotal one for them, witnessing the release of the album ’20 Jazz Funk Greats’ and performances in Northampton with the fledgling Bauhaus and at London’s YMCA.

Tempting though it is to see TG as a proto punk band simply because they existed within the same orbit at the same time and crossed over with key players in punk like Mark Perry and Crass, is a mistake. They, and Coum Transmissions, were a self-consciously arty project of the like punk professed to blow away (but never did, as early punk was in essence an alternative art movement itself) and never really sat well with the less intellectual pub rock tone of punk. TG themselves may have started out performing at academic and arts institutions in the first instance (although none possessed a formal art school training) but soon progressed on to more conventional rock venues and bills, even playing with Joy Division in support. That contradiction between their high-minded commitment to simultaneously destroy and re-model art and music, and the more humdrum reality and economics of rock performance is one of the defining challenges that ultimately derailed and diluted early industrial music and turned it into the side show we have today.

Analysing and dissecting in print a band like TG was never going to be an easy task. In many ways it was doomed from the start as TG were never a band in the conventional sense and defied categorisation, despite the ‘Industrial’ tag. However, to his credit Ian Trowell has succeeded in producing a book which melds academia and counter culture and comes out with a fascinating insight into a world that blinked into existence only briefly before the mundane world diluted and destroyed it as a unique thing. His knowledge and enthusiasm are infectious in their nature and even discarding the rose-tinted spectacles of nostalgia, it is clear to see that there was something innovative and different going on in those grubby back street locations.

I will leave TG train spotters to pore through the detail picking out any small inaccuracies, of which there are bound to be a few, but for me it brought back memories of that scene, not least of which was how bloody cold it always seemed to be back then and how everyone was always broke! Whether the music produced by TG has stood the test of time is a moot point, but from this distance you cannot deny that they had a huge influence on electronic and industrial music today and ‘An Endless Content’ successfully captures what made TG special. Mission accomplished I’d say.

Interesting what you say about the ambivalent relationship between TG and Punk. TG collaborated with Derek Jarman, who enjoyed a similar relationship with it: his film Jubilee, although denounced by Vivienne Westwood and others as a mockery of Punk, is at the same time a favourite among many punk fans.

Comment by djrivron on 6 January, 2024 at 12:18 pmThe original punk scene was a contradictory beast. Driven by clothes designers like Vivien Westwood, Barrow Boy chancers like Malcolm McClaren and Berni Rhodes, or graphic artists like Jamie Reid and Barney Bubbles, it struggled to maintain that it was a street level movement, at least in the capital. Cosey apparently hated punk and its often clunking pub rock sound wasn’t the revolution that it was portrayed as.

Comment by Alan Rider on 9 January, 2024 at 11:04 pm