Sweet Dreams. The Story of the New Romantics, Dylan Jones

(680pp, hbck, £20, Faber)

One of the most interesting things about this book is the breadth of Dylan Jones’ coverage and discussion; but this is also problematic. I’m always pleased when authors don’t ring fence themes, topics or movements and look at the edges, where the most interesting things often happen; also when they give social and critical context. Jones does both, he also allows others to offer their opinions and points of view: this is a book of carefully curated quotes from those who were there at the time interspersed with Jones’ own research and opinions.

The book actually starts by covering punk, highlighting the brief flurry of energy and originality that happened mostly in London and Manchester before it fizzled out: the DIY nature of it all reduced to copycat bondage trousers, leather jackets and spitting, the music to recycled pub rock. So far so good but Jones and many others included here, buy into the idea of postpunk being dull, grey and serious– totally missing the innovation, energy and danceability of the likes of Magazine, early Simple Minds, XTC and Gang of Four.

Having written off what punk became and choosing to mostly ignore post-punk allows Jones to buy into the whole myth of 1970s social depression and nihilism that prevails to this day as the central narrative of the decade, and to present a small bunch of dressed-up partygoers in Covent Garden as the saviours of fashion and the music industry, which of course they weren’t.

The 1970s were a fantastic time to grow up in London – it was cheap to live, easy to get casual work, and there was endless live music at pubs and clubs and colleges throughout the city and its suburbs. For me, the 1980s were when Thatcher & co. started stomping on society and life got harder, with people being far too busy worrying about their bank balance and what they looked like in the mirror.

Jones is pretty defensive about any accusations that the likes of Spandau Ballet adopted conservative (or heaven forbid, Conservative) views and attitudes, preferring to use that dreadful word ‘entrepreneur’ as a way of positioning the financial side of the magazines and music that he claims the New Romantic movement produced as survival and innovation rather than business. He doesn’t deign to discuss the fickleness of judging a person by how good-looking or fashionable they are, or the vagaries and problematic ethics of the fashion industry, preferring to constantly reiterate how D.I.Y. and radical all the dressing-up was.

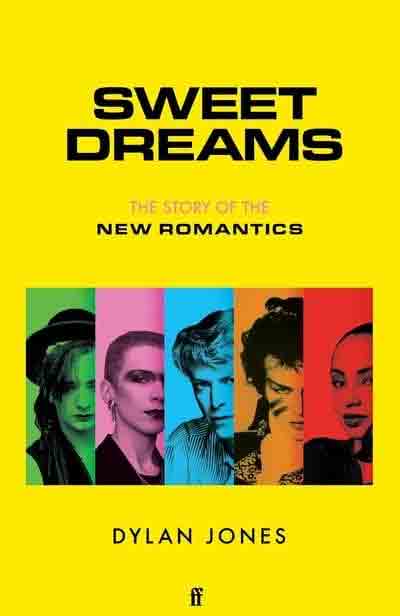

The cover of Sweet Dreams is confusing: none of the five photographs present what I would regard as a New Romantic; I’m pretty sure that I am not alone in regarding the likes of Eurythmics and Sadé as 1980s pop stars. Intelligent pop stars, yes, but little to do with the party people who emerged from Bowie nights and small clubs like Blitz in the late 1970s (whether or not the people involved hung around there). I saw Eurythmics at Keele University the week before their first hit single entered the charts and there was little visually stylish about them; Dave Stewart remains rooted in 70s rock chic to this day. The music was, of course, innovative and highly reliant on krautrock influences and what the band had learnt from Conny Plank (who produced their first album); the band basically used their new toy, a Fairlight, to disrupt and extend the pop sensibilities they had practiced and refined in The Tourists. On this tour aided and abetted by Blondie’s Clem Burke on drums and vocalist Eddie Reader.

Jones is well-informed about music, however, although he sometimes seems to buy into Malcolm Mclaren’s own storytelling, and gives far too much coverage to George Michael and also to Gary Numan, who – for good reason – has always been a musical laughing stock. Numan is not alone, of course, in his recycling of David Bowie, a point which Jones consistently makes throughout this book. Bowie seems to be the godfather of it all, everyone agrees, and he is a presence throughout the whole of this book; as are Roxy Music, although Jones unfortunately chooses to focus on Bryan Ferry and later Roxy rather than the more interesting and experimental early version of the band with Eno.

Elsewhere there are some hilarious quotes, such as Simon le Bon claiming that Duran Duran were an experimental band and Midge Ure going on at some length about how he single-handedly reinvented and saved Ultravox, along with a lot of po-faced seriousness from has-been or would-be pop stars who should know better by now.

But this is a delightful and comprehensive whirl of a book. If it takes fashion and image and pop music more seriously than I do, and perhaps gives space to too many stars and their exaggerations and claims to fame, it is a small price to pay for a wide-ranging and intelligent volume about music, culture and society. It isn’t, of course, just a history of the New Romantics, it’s a history of music and youth culture from the mid 70s to the mid 80s, perhaps even a history of the 70s in the same way that people have said the Sixties didn’t begin till the middle of that decade and carried on until 1974 or ’75. If you have any interest in how Britain moved from hippy ideals to yuppie greed and Thatcherism via punk, or in synth pop, dance music and 1980s soul, then this book is for you.

Rupert Loydell