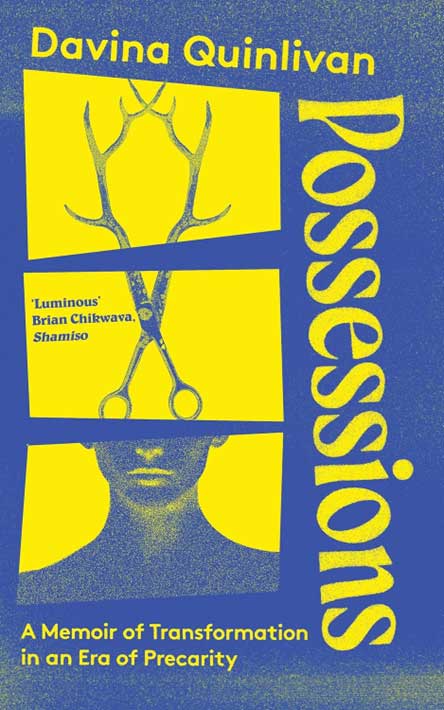

Possessions, Davina Quinlivan (229pp, September Publishing)

Possessions is an almost hallucinogenic, dreamlike memoir. Throughout, the narrator is hyper self-aware and lost in the delusions that friends, authority, fashion and academia want her to conform to. From childhood worries about being ‘other’ and not looking right, to a realisation she is not the ‘academic Barbie’ required by universities for their neoliberal teaching and research, via the struggle to be a good parent and earn enough, Quinlivan navigates familial expectations, feminism, racism, epiphanies and breakdown.

She does so as a kind of contemporary shaman, travelling through time and place, talking to her ancestors, her dead parents, her previous and future self, students and colleagues from long ago and the present, and directly to the reader. Unable to conform to the university system she is meant to be part of, everything is brought to a head during lockdown and the move to online teaching: the ghosts in the machine, the silent, uninvolved and invisible students on Zoom classes, are too much to bear and the world spins and becomes untenable.

The university where she worked (it’s not named, though I can make an informed guess) clearly took a different attitude to my one during lockdown. My institution prioritised student welfare, conversation, contact and wellbeing, our imposed ‘flexible learning’ became just that: flexible. It’s quite a shock to find out that anywhere does 2 hour lectures, in person or online, when studies have shown for decades that 20 minutes of being talked at or to, however entertaining or sprinkled with jokes and visuals, is the maximum most of us can bear. Lectures and seminars require pace and momentum, changes in activity…

So, I was fortunate, and did not have to try to replicate lectures and 2 or 3 hour seminar workshops online. We could start a session, set online breakout rooms up for small discussion groups or initiate writing tasks and then regroup later that day or week to share and review work. We recorded our lectures (in short parts if necessary) and let the students watch them when they were up to it: felt well enough, motivated or could simply find time amongst the chaos of lockdown. We arranged extra tutorials as well as cross-curricular and multi-cohort (year group) support sessions. Quinlivan, it seems, was expected to somehow replicate all her teaching – which seems to have been way above the agreed national maximum contact time – online, even thought she was also home schooling and dealing with her own personal demons, even though she was part-time and on a fixed-term contract.

Sometimes, I find it hard to empathise. In my place of work we simply refused to do more teaching than we should unless student lives or health were in danger. During lockdown, attendance was not monitored (engagement and assessments were), and the word counts of submission were reduced or different forms of assessment introduced. Possessions makes me realise how liberal my place of work really was, how generous and caring it tried to be (and often was).

But I do empathise with the crunch point Quinlivan reaches. I had a kind of breakdown after lockdown ended, when realisation of what we/I’d endured kicked in, and stress and anxiety belatedly arrived as normal timetables and in-person teaching returned. Quinlivan’s experiences are different, and this whole book is self-experiential, birthed from that period of lockdown isolation and digital loneliness. These only accentuate her sense of being lost in the world… How does her Burmese ancestry work in 21st Century Britain? What are the expectations for a woman in a Russell Group university? Why can’t her university management and colleagues cope with intelligent, informed and innovative ideas? How does anyone raised in London deal with the weather, traditions, racism and isolation of living in the British countryside? Why can’t lived experience inform teaching and research?

Unlike other books which formally examine the failings of the neoliberal hijacking of universities (I particularly recommend Peter Fleming’s Dark Academia: How Universities Die), Possessions explores what it feels like to be part of the machine that higher education has become, prioritising money and efficiency over motivational learning and teaching, bullying and persuading its front line staff in the name of streamlining and futureproofing. The idea of teaching students how to think and learn for themselves, of open-ended discussion and debate, has been replaced by ‘how to’ seminars and the yes/no/tickbox answers already prevalent in UK schools. Instead of encouraging wide-ranging reading and understanding, informed debate and open-ended and ever-developing understanding, students are given the idea that there are right and wrong answers, and academic institutions are judged by the percentage of graduates who have certain incomes or managerial levels of employment.

It’s good to reminded how this kind of bullshit is taking its emotional and mental toll on university lecturers and teachers, who mostly want to be doing their jobs because they are passionate and knowledgeable about their subject and want to share that with others, learning and exploring new ideas. Very few think of themselves as oracles of wisdom or receptacles of information that can somehow be imparted or transferred to empty-headed students; good teaching is about enthusing, sharing and encouraging. Quinlivan’s book cuts through the educational crap that politicians and management have produced in the last few decades and reminds us of what is possible, what might be; what our priorities should be. It is at times overwrought and often peculiar, has an unfortunate clunky end chapter about a robot lecturer which is not as funny as it thinks it is, and is mystical and emotional in a way I don’t normally engage with. But is also startlingly original, passionate and powerfully persuasive.

.

Rupert Loydell

.