The man who recently came to fix my bathroom tap told me that his son, aged 14, was so disillusioned with music being made at the current time for people his age that he decided to have a go at the classics of the 1990s. Nirvana, Queens of the Stone Age, Smashing Pumpkins, Red Hot Chilli Peppers – and Dinosaur Jr. Not long later he watched a video on Youtube of Dinosaur Jr as they are now, promoting their new LP. He saw a group of middle aged men skateboarding. He was so disgusted he hasn’t listened to them since.

Time was that one’s music affiliations were tribal – Beatles vs Stones, Mods vs Rockers, Stax soul vs Motown, punks loathing almost everyone, very often themselves specially. Your music of choice was a key part of your identity, and came with clothes, haircuts, posters on the bedroom wall, and all the rest as part of the package. Music was less widely available as a consumer product, and if you bought an LP it was so expensive you almost had to convince yourself you liked it. That world is long gone.

During the lockdowns of 2020 there was much debate about Boris Johnson’s government failing to support the arts. In my experience, Tories have always been committed philistines, so no real surprise there. The real irony for me though was that it’s not just government – or the royal family, or whoever – passively disparaging the arts through their lack of interest – artists also very often fail to support other artists. Someone else’s success – anyone’s – entails your own failure. For the average struggling undiscovered genius mainstream journos are little help. In the 2019 movie How to Build a Girl, the central character, wonderfully played by Beanie Feldstein, gets a job in the 1990s at was clearly meant to be the NME. A cynical staffer there tells her that their remit is to give support to the 20 favoured artists du jour and to blow all other comers off the mountainside. In the intervening 30 years much has changed, but the basic paradigm remains the same. The route for the aspiring chart-topper now is not to work their way up through the clubs playing night after night in dingy toilets and throwing up in the back of the van on the way home, but to do stage school or a course in sound design at Uni, get in a PR team and social media manager and to pin one’s hopes there.

So I decided during the last series of lockdowns that I would support other artists. My friend Richard Cabut, sometime scribe for this august journal, told me that his most-played LP during that period was Dark Jazz, the latest release by my band Necessary Animals. I knew this was not idle and disingenuous flattery – it would not be in him to do that. I also knew that he had really listened. I was dead chuffed.

In a similar way, one of my favourite albums of last year was by Philip Sanderson, founder member of Storm Bugs, avant-garde sound artist, historian of cassette tape culture, visual artist, experimental filmmaker and seasoned tunesmith whose label Snatch Tapes has a series of excellent releases on Bandcamp. Philip and I have shared history. In 1980 we both played on the bill at a punk weekender in Maidstone’s Motcombe Park, organised by my long-term friend and collaborator Dave Arnold. I was in the Good Missionaries (sans Mark Perry by this time), Philip in Storm Bugs.

Thirty years later we collaborated on a series of events for Trash Cannes Festival, where I am creative director. Our last planned event was scuppered by Covid. He did though send me an advance copy of his album Rumble of the Ruins. I was hooked. Now, he has a new collection of his idiosyncratic tunes in the pipeline, due for imminent release.

Trying to describe music in reviews, or make the inevitable comparisons to other artists is not something I warm to, so in a moment of hypocritical cognitive dissonance, I’m going to suggest that Philip is something like a one-man post-punk independent-artist revivalist. His music carries echoes of American avant-garde band the Residents, Brian Eno, John Cale and Anthony Moore. The tracks on both last year’s Rumble of the Ruins and the forthcoming release, Not Even My Closest Friends, weave a sonic web of synths, keyboards, programmed drums and vocal harmonies , with Philip’s very English vocals declaiming a kind of detached bemusement at the world and its many vagaries. The track that inspired the album’s title, Bye, seems to be a phone message from his father – from someone’s father at any rate- imploring the recipient not to give out his phone number, ‘not even to my closest friends’. It’s an intriguing moment in an album that is both uplifting and curiously unsettling. Judging by the number of supporters he has on Bandcamp, it seems Philip has at least a modest fanbase – but this is music that deserves to be more widely heard. Getting oneself heard in a world swamped with music, much of it good, is a conundrum that exercises even hardened music biz veterans.

For Dinosaur Jr, releasing albums in middle age of music that sounds vaguely retro but weighed down by forces imposed by the passage of 30 years, and then making a video of oneself looking utterly ridiculous, probably won’t help. For us ageing bedroom producer -groovers, even the chance to be consciously ignored by a younger audience might seem like a step up, sadly.

Not Even My Closest Friends will be available on release on Bandcamp – https://snatchtapes.bandcamp.com – and a physical release of some kind is allegedly in the pipeline.

I conducted a remote interview with Philip a few days ago:

KR: I first became aware of your work in 1980, when we shared a bill at an

all-day punk event in Motcombe Park in Maidstone. How would you

describe your work with Storm Bugs, and where did things go from

there?

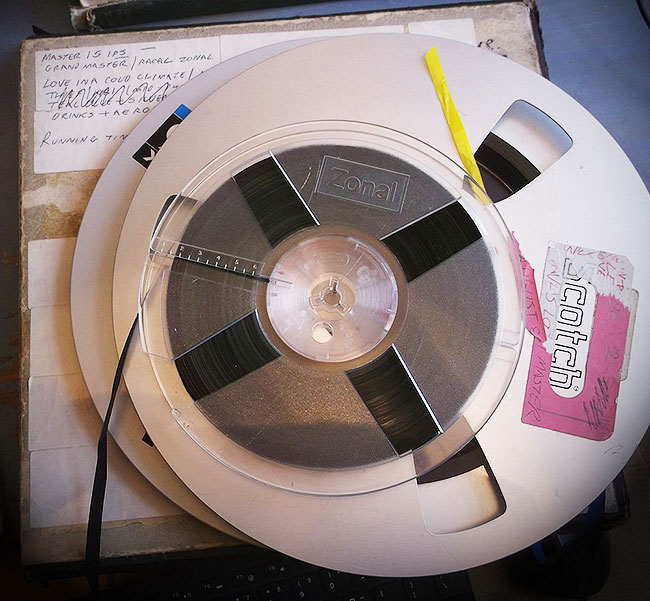

PS: The gig we played with you in Maidstone was something of a one-off as

Storm bugs was very much a studio or bedroom recording project rather

than a band in the regular sense of the word. It was all very DIY with

electronics and circuit bent radios, tape loops and scratched records.

At that time I had access to the Goldsmiths electronic music studio

set up by Hugh Davies and so quite a few of the recordings employed

the full range of equipment found there including VCS3 synthesizers,

sequencers and so on. Overall Storm Bugs would fit loosely into the

industrial/noise category, but with more humour. In 1980 we released

an EP on vinyl and an album on the Snatch Tapes label called A Safe

Substitute, which has recently been re-issued on CD by Klanggalerie.

In the following year, 1981, Storm Bugs had a second single released

called Tin, and then the project went into hibernation. I

began experimenting with different approaches and collaborations; for

example working with a couple of female singers, mixing electronics

with vibraphone and recording soundtracks for friends making short

experimental films. A selection of these tracks was compiled

on the On One of These Bends LP that came out in 2019.

KR: How would you describe your work as a visual artist? What were your

formative influences, and how has it developed over the years?

PS: During the Storm Bugs time I was constantly cutting up magazines and

making collages, and had a strong interest in visual art but aside

from winning second prize in a primary school painting competition had

had no art training. Working on the soundtrack projects for other

people gradually encouraged me to start making Super 8 films and

videos myself. I took a year-long 16 mm course with Paul Bush and got

heavily involved with the London Filmmakers Co-op in London. It was a

great opportunity to see lots of experimental/artist film. With the

help of grants from South East and London Arts board I made a small

number of short moving image pieces and then started working with a

range of electronic circuits to link sound and light together to

create installations. This was in the 1990s and the heyday of the

alternative space in London, and I showed work in a former bus garage,

fire station, church vestry, hat factory, and my own flat to name but

a few unorthodox venues.

In the late 1990s I was back at the Co-op helping with the move to the

Lux centre and began using the Apple computers they had there. I soon

bought my own Mac and this encouraged me to start making single screen

work again and also recording music. I eventually did an MA in fine

art and then a PhD in the noughties – all a little back to front.

KR: Currently, much of popular music seems tied up with self-promotion,

personal brands and a kind of theatrical narcissism [this of course has long been the case for solo pop performers, reaching back to Bowie, and probably further]. The musical

content seems to take a backseat. Is this simply the view of someone

from a generation who thought they invented popular music, or is music

adapting to its social and cultural environment, and the expectations

of a generation rejecting conventional notions of what music is and

how it should be made – or is there something else going on?

PS: About three years ago I was teaching a class of students and whilst we

were looking at some pictures online I noticed a figure in one of the

shots and said idly “oh look Bryan Ferry”. I immediately realised that

nobody in the class had either recognised Ferry or for that matter

knew who he was. I was a little taken aback and then wondered if when

I was 25 would I have recognised artists whose heyday was before I was

born. Buddy Holly and other early Rock N Rollers yes. People from

Dixieland revival probably not. To a lot of people under 30 artists

like Roxy Music or PIL who people of my generation consider to be

significant beyond their status as musicians of the times are no more

relevant than Harry Hump and his Hill Street Hoofers were to us. That

thread or trajectory that starts in the late 1950s with the birth of

Rock n Roll and seemed to lead inexorably onwards, in some way binding

everything together, broke down somewhere in the 1990s, and music

became segmented, atomised and factionalised. There are lots of

paradoxes; simultaneously popular music became ubiquitous, and yet far

less important. In the glory days of the NME, it didn’t seem too

ridiculous to tie intellectual discourse to popular music whereas the

majority of writing that takes place now about music is by the over

50s for the over 50s. In a sense popular music has returned to the

more relaxed cultural role it has pre 1958.

KR: How would you describe the music you are currently making? Where does

it fit with other music being made today?

PS: The music I started making after getting a computer in 1997 was

largely instrumental, in some ways a continuation of what I had been

doing in the late 70s and 1980s, sometimes very self-consciously so. I

had always been interested in the song as a form and gradually the odd

vocal tune began to appear amongst the instrumentals. The song writing

style is a little unorthodox as what generally happens is that I

record a sequencer pattern in a way not dissimilar way to how some of

the Storm Bugs tracks were recorded. I then sing over these,

improvising until a verse and chorus appears. There is then a long and

occasionally torturous process of adding all the parts that turn the

track into something approaching a more recognizable song structure.

There is that term Baroque Pop used to describe some of the lusher

strands of 1960’s pop music and one might characterise the songs on

the new release as Baroque Bedroom Pop.

As to where it fits, that is the question. Though the linear

trajectory of popular music that has broken down the three-minute song has

a history that goes back to the time of the travelling minstrel and in

a way I am trying to connect with that broader seam. I don’t think for

a moment that these numbers will be bothering the charts anytime soon,

but being so out of sync with what is happening may give the songs

a weird longevity. Always out of fashion so to speak. So the audience

is small and select, join up to be in the best of company.

KR: Do you have any gigs planned?

PS; The number of live performances I have done is by most standards tiny

and that stems less from any antipathy to performing as to the music

having come together in the studio rather than through playing per se.

When I have performed live either on my own or as Storm Bugs (with

Steven Ball) I often feel as if I am trying to recreate something. It

is an inexact and slightly naff analogy but it can be rather like

re-painting a picture but in front of an audience. To perform the new

album would need either a well-honed five-piece band or a lot of front

to simply sing along with a full backing track. So the short answer

is no, but after a year spent at home, along with everyone else I’m

keen to get out there and do something visceral.

Keith Rodway

The voice heard on “Bye” is that of Gustav Metzger and is taken from an answer phone message left by him on the night of the Private View for an exhibition called Gustav Metzger is my Dad which took place at Camerawork Gallery in the late 1990s. You can read more about the show here http://stormbugblog.blogspot.com/2005/10/gustav-metzger-is-my-dad.html

Comment by blanket77 on 22 May, 2021 at 8:44 am