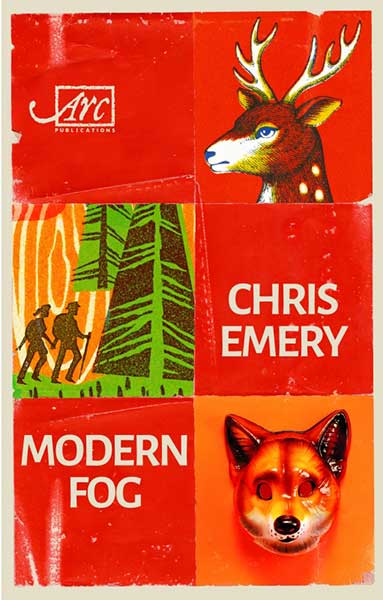

Chris Emery is a poet and director of Salt. He has published four collections of poetry, with the most recent, Modern Fog (2024), being described as a collection of “elegiac, tough-minded poems of marked originality and scope”. With “attentive, atmospheric, musical poems” that “can light up everywhere: seascapes, edgelands, interiors, even a carpark”, his “art is at once earthy, spiritual, dreamlike and exact”.

The Departure (2012) has a series of narrative poems that reveal an astonishing range of personas, from the set of Mission Impossible, an extra from Gojira, porn stars, bombers and executioners — even Charles Bukowski turns up to take a leak. Radio Nostalgia (2005) examines the borders of war, social exile, and manufactured liberty expressed through corporate media, while Dr Mephisto (2001) traces Mephistopheles as he ranges freely through time and space, always a presence wherever there is conflict and suffering and whenever there is work to be done.

Together with his wife, Jennifer, Emery founded and has run Salt since 1999. Their first publications were poetry and they rapidly developed an award-winning international list. In 2008 they won the Nielsen Innovation Award in the IPG’s Independent Publishing Awards for their work in taking poetry to new audiences. They have subsequently expanded to include children’s poetry, Native American poetry, Latin American poetry in translation, poetry criticism, essays, literary companions, biography, theatre studies, writers’ guides and poetry chapbooks as well as a ground-breaking series of eBook novellas.

From 2019 to 2022 Emery was first Director of Operations and later, additionally, Director of Development at The Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham – a major pilgrimage site dating from the eleventh century, situated in rural North Norfolk.

He is currently working on three new full-length collections of poetry:

JE: You are a poet, publisher, and writer, with four collections of poetry, more on the way, plus a significant career in publishing, particularly with Salt. That represents a major achievement in the world of British poetry but your journey to that place has not been straightforward with lots of work destroyed, issues in balancing writing and publishing, plus the challenges of maintaining a small independent publishing company. Could you try to summarise for us the arc of that time with its issues and achievements?

CE: I started writing as a child and the fascination stayed with me through my time at school and on into my creative studies at Leeds Polytechnic in the 1980s. I kept writing through those years at art school. It became more serious during the Nineties, long before I considered publishing as a career – not that that I think of publishing as a career. Through a series of missteps, I ended up as a junior manager at Cambridge University Press and worked my way up the ranks, becoming a director. Certainly, at that time, I was passionate about writing. I mean obsessed with it and being in Cambridge I ended up meeting many of the writers living in that city. That was quite transformative.

I wrote several collections that have never seen the light of day and the work has all been lost. Yet by the start of the new millennium there had been a major shift in what I wanted to write. I was experimenting with these wild pieces that were influenced by manga, European cinema, political theory, grimoires – this mash-up of influences led to a break with tradition and used a range of personae to write in. My debut appeared in 2001. Anyway, after that, I knew I wanted to leave corporate life and set up a publishing house of my own – the plan was to finance a writing life free from too much senior management – of course, it was a terrible mistake. It was desperate for the first five years – no money, no prospects – I mean, nothing changes. But Jen and I hung on. A new darker and more fragmented collection emerged in 2006 and then … well, then Salt swallowed me up, I think.

I think I lost faith in my own experimental writing and what it could achieve; this may be heretical, but I came to see my own practice as old fashioned, even hackneyed, a kind of simulated avant-garde and the last thing I wanted to do was to see my writing life as some form of reenactment of early 20th century experimentation. We had that; it’s in the past. I came to distrust my own innovations and saw them as a cul-de-sac. I wanted to do something different, but I needed a new path. I think my third collection, The Departure, was just that, a move back towards the reader.

JE: You said once that “nothing has had a more lasting impact on my obsessions as a writer than this [convent-run] schooling”. Given your recent role as Operations Director at the Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham, could you tell us about the lasting impact your schooling had and any connections to your recent experiences and poems?

CE: I’m always nervous of documenting one’s origins, I mean we rewrite our lives to fit into our choices, don’t we? I was brought up as a Roman Catholic and I had deep convictions as a child. My primary school was run by the Presentation Sisters – an Irish movement that came to Manchester to care for its poor. The convent was in the school grounds, and the church was on the other side of the school buildings. We sort of grew up between these two symbols of vocation and community. I was thinking about this the other day and I’m certain I began writing there – but it’s all very long ago.

Anyway, we are talking about the Seventies here and there were still vestiges of sectarianism in Manchester; being a Catholic had a sense of being different, being other, and I think this sense of having beliefs that run counter to the world you inhabit fed into my personality and my own narrative. That whole thing of Catholic formation stayed with me, even when I rejected it, and I rejected it absolutely, as so many of us do, though, you know, it was still there as this additional, expansive, signifying world. And I came back to it, of course.

Forty years had passed, but I was walking in Norfolk with my dog and had what I can only describe as a reconversion. The thing about deep convictions is they can be deeply overturned. I was standing looking out over Beeston Regis and All Saints church and the bright sea and sky and was … well, I don’t know what it was; called perhaps. A week later, I had made my confession and was back in my local church to see, to feel, what was happening to me. It was profoundly discomfiting but also emotionally charged. It can only have been a month or two after this that a vacancy appeared at the Anglican Shrine in Walsingham and I eventually applied for and got the job. So, I stepped out of publishing and had the most wonderful time working for the Shrine for three years. It was one of those pivotal moments in my life.

Allowing myself time to fully engage with a spiritual life was transformative. I felt liberated from my own prejudices and I think the experiences working there led me to consider deeply how we impact upon and share this world with each other, both physically and in language – I think it’s true to say that this had a significant effect on how I was writing as much as what I was writing. As I mentioned, I wanted to let the reader in, to enter a shared linguistic realm – I saw my experimentation as a barrier.

You know, so much of my early work was an attempt to use language to foreground the fractures and deceits in our political lives. Suddenly, I was finding other techniques for exploring what I wanted to say in what I hope is a more approachable, even amenable, memorable language. And within all that was something else, a sense of giving people permission to share in what we all recognise as beauty and fragility in our world. Once you do this, open yourself to mystery, a great deal opens for you as a writer.

JE: As you’ve said, your first two collections were experimental in nature and were inspired by your connections to the Cambridge School and the continuing effects of the British Poetry Revival. You also published many of the key figures in the scene. How do you view its influence on you and your writing now and what do you think its eventual significance will be seen to be within the history of twentieth century British poetry?

CE: Actually, there were several collections before I discovered the Cambridge scene – I remember Richard Caddell gently questioning my convictions about experimentation – he was right too, as well. Drew Milne’s work, John Wilkinson’s work made a very deep impression on me. Once I allowed myself to engage, the scene had a huge effect on my writing. I dived in. Publishing came a little later – it was all part of my migration out of corporate life into something more fugitive and romantic. I gave up a career to pursue poetry. I don’t think history will care much for my choices, or my publishing – trade publishers are rarely celebrated in the history of letters. Who was Austen’s editor? Who was Wordsworth’s editor?

Our job as publishers is to allow the best talent to find its readership in time. We never know. What I do know, from the inside is the mechanics of reputation and the fragility of readerships and the appurtenances of fame. Much of what we do is simply dust. But you ask about influence and I do think that there is a powerful influence from the writing I encountered at this time – a sense of finding the boundaries of what can be said, and how to say it. A sense of being inside the saying of things, more than using the language figuratively. The way of saying often being the subject and torment of a poem. How language makes us. And then, the limits of this, how following this path in extremis can lead one away from what we want to achieve. What gets lost is what can be communicated through time.

We’re left with vestiges and fragments, and we create readerships that are vestiges and fragments, I’ll say more about this later. This can be a political aim, of course – the desire to build elite communities of reading; coteries. But this is disordered thinking, at least it is for me.

JE: Which poets have inspired and/or supported you over the years and what has their influence meant for your work?

CE: This is a great, hard question. What I may cite here, I can easily abandon in six months or six hours. I’ve mentioned Milne and Wilkinson, whom I love. I love early Prynne – though I’ve not read him for a decade. I love Ruefle and Mary Oliver. Pitter, Shapiro, Shaughnessy. Popa, Plath and Hughes. Caroline Bird and Hera Lindsay Bird. It all gives me immense pleasure. But I could reach back and say so much more about 17th century lyrics, the Romantics and so on.

However, I think the deepest influences aren’t really poets at all – they’re perhaps painters and filmmakers, composers, and novelists. That world of influence also must refer to the communities we live in: our people, as it were. And the deep land. The sea beyond the shingle bank. Cliff falls. You know, all that stuff that reaches in and rinses us out like a crazy dawn.

JE: As a publisher, what changes do you think have been apparent in British poetry over the course of your career and what excites you about the poetry scene today?

CE: Polyphony. I mean, there’s been an explosion of new talent, and not just from these shores – we had a period of constraint in the range of writers we could see, but from the early Noughties, I think a mix of new types of publishing, greater accessibility to forms of distribution, Amazon to some extent, and the industrialisation of creative writing has led to an exciting expansion of new poets and new forms or writing. Some of it is reaching back to earlier forms of practice, some of it is looking across the Atlantic, some is looking farther afield for its provocations.

There are tens of thousands of poets. Social media has brought many into view and for the people who care about poetry it’s a very exciting and expansive new landscape where many, many forms of practice coexist and try to develop their own readerships. But there’s a cost. What we have also seen is that this rapid nurturing of poetic communities has developed a new insularity – and the whole art has moved away from the larger society that it needs to serve.

The expansion in practice has not led to an expansion in the audience for poetry. And the many poetries we currently have – and that are to be celebrated – are becoming on the one hand more fractured, more etiolated, more disengaged, smaller in outreach, whilst other branches of the art have reached down into aphorism and identity, wellness and, you know, the banal.

Some find followers in their millions; others barely reach fifty people. As the assertion around new voices has taken hold, the critical space has also failed to keep up. There’s such an abundance we cannot address it. I think there is a risk here, for publishers especially, that if we don’t develop audiences, poetry will become a widespread but unread genre. It’s leading to a poetry of low aspiration. But we’re seeing this across the arts and it’s not specific to poets.

JE: How difficult is it in reality to run a small independent publishing company that includes a significant strand of poetry within your publications?

CE: There’s a short answer to this – in the main serious poetry loses money. You have to be able to afford it. This means becoming a publicly funded press, in part coordinated by our Arts Council, who really do terrific work in extremely pressing times, or you finance the genre through your other publishing activity, cross subsidising it. Some fund it by taking no salary and have collaborators who take no salary – keeping the venture as a noble hobby. But if you want to pay people, staff, invest – there are only two models I can see: State subsidy or financing from other publishing activity. We’ve done both, and right now, we need to draw back and build a war chest for any further poetry publishing. That will take time, possibly some years.

JE: Your early work was often written in character and was deliberately not confessional. To what extent has that strand of your work continued and to what extent has your personal life and experience come to feature within aspects of your poetry?

CE: I’m not remotely interested in me or any revelations about me – I mean there’s enough of me in my personal life! The primary purpose for my own art is to explore the Other – the fictions of ourselves, the possibilities and multiplicities of life. The ‘me’ that appears in some of my writing is not biographical, even when there are biographical tropes. As you may gather, I rather jar at the personal. However, I respect it in the work of others – this isn’t a call to arms or manifesto for the abandonment of identity in writing. It can be extremely important for poets to be seen, to have their experience seen, their communities seen – it’s just not important to me. However, I would be deceiving if I made claims that I don’t have some obsessions that travel through my writing – though without wishing to be coy, I think the writer is often poorly placed to see all of this clearly. I recently wanted to write about what it’s like to be leaving middle age and to be in that hinterland – you know, not yet old, but not certainly no long in those middle years. They rush by us, don’t they? And that sense of the eschatological is an important theme in my recent work. Meaning and vocation, the deceit of purpose and the reality of it – what we choose, how we choose to live.

JE: Your four collections all seem very different, with The Departure, in particular, signalling a particular change in style. What factors have contributed to the developments in your work and in what ways is Modern Fog another shift in style and content?

CE: The Departure is almost a pun, isn’t it? It was partly about the physical departure from Cambridge to Norfolk, and more importantly from one life to another. We even changed the business – Salt moved away from poetry into fiction publishing. I look at it now and think of the book as a form of personal exile. Or given my recent experience, perhaps of pilgrimage – that whole notion of moving into a liminal world, a world of exposure and encounter. I wanted to shake off the late-Modernist tropes and try to find a range of voices that could be, well, playful, joyous, comic. It was a move back to the centre of the art from its outer rim. Modern Fog is a hymn to nature, to the Earth and our place in it. It certainly plays with geographic and geological language and familiar bucolic themes – but I hope it extends these with multiple possible meanings and can introduce people to poetry as meditation and even prayer.

JE: Where are your next collections and your current writing taking you?

CE: I’m working on three collections; they all expand on using short story and fictional techniques to place us in times and places that allow us to dream of other ways of living. I’ve started to think that these collections will collide and contract – contraction is always a healthy impulse with poetry. So, we may see something cut back, sewn together, thematically cohesive but certainly it will continue with these themes of what it means to be here and what moral choices we have in sharing the Earth with other species through time in a universe that has no other signs of life. As far as we currently know, the species here is all there is of life, this Earth is it, and it’s not ours. It’s simply not ours.

JE: Your poetry is characterised by unexpected images and unusual phraseology. You said at an earlier stage in your career that you “always like to have surprises in my writing, so I tend to judge a first draft by how many shocks I receive in terms of the vocabulary and sweep.” To what extent has that sense of seeking to provoke continued to inform your work?

CE: Oh, if I’m bored, you certainly will be. All art should provoke emotion, even before any meaning. The poem is itself a space for encounter with the mystery of language; it is, I suppose, its own universe and the challenge is to – let’s say, terraform the planet we create inside the poem! That’s a terrible analogy, but for any writing making the world of the poem feel real is paramount. So, I love creating little challenges for myself, that can be new forms of practice or fresh attempts and models and topics, you know, ‘I’ve never written a poem about dishcloths’ – and off you go writing about dishcloths and what they mean. The simplest provocations are often the best. Writing about late-stage capitalism and disestablishmentarianism – I mean, why bother? But you know, dishcloths. That might be it for a week. The poet has to be personally radical you have to disrupt yourself as well as the world we live in. My advice to poets is this, ‘If you have found a voice, now lose it.’

JE: Of what are you most proud about Modern Fog and of what about Salt?

CE: Goodness, I think seeing it published is simply wonderful. I really didn’t think I would be published again. I don’t sit well in the current fashions and trends for poetry – I’m an outsider, and I’m sixty and still emerging. It’s laughable really. But Modern Fog is a book for my late mother-in-law – actually, more than any other book of mine, it is a book for others I admire and love. Returning to Arc, who published my debut, is also wonderful. A great publishing team with an amazing backlist and history. I really do cherish that. I’m also proud of where it might lead me in the next phase of my creative life.

Salt is entering a new phase in its development – we’re planning to grow it, to do more fiction, move into non-fiction, explore new strands. We’re working with others to develop our business planning and, after twenty-five years in the business, I feel a new hunger to take the press forward, to build it, to do something amazing and to share it.

Modern Fog, Chris Emery, Arc Publications, February 2024, ISBN: 9781911469544

by Jonathan Evens

.