‘Good authors, too, who once knew better words, now

only use four-letter words, writing prose, anything goes…’

(“Anything Goes” by Cole Porter)

Cinema conjures with light, cinema is ‘a chisel of light cutting into the reality of objects’ according to art theorist Herbert Read.

But it’s always flirted with darkness. As early as the 1820s ‘Magic Lantern Shows’ were evolving from still slides into a variety of ‘moving picture’ projections, with the Praxinoscope, the Zoescope, the Thaumatrope, and the Stroboscope, all devised to fool and seduce the eye by accelerating static images fast enough to blur into motion. They operate on understanding the principle of the persistence of vision, that when different images succeed each other very rapidly, the eye can’t eradicate them quickly enough, so that they merge – which is the basis of cinema.

Previously there’d been strange animation devices such as the phenakistoscope that project a flickering repetition of images in rotation to invest them with the illusion of motion. Eccentric photography pioneer Eadweard Muybridge took sequences of photos in a kind of early stop-motion technique, freezing time to accurately document the movement of galloping horses for the first time. He also, inevitably, took nude studies as scientific research into muscle-tone in human activity. Including naked athletes and dancers, a collotype of two nude boys playing leapfrog (1883), and two unclothed young women, one standing, one seated, in 1887. Sponsorship from the University of Pennsylvania enabled him to involve banks of cameras, the results of which are capable of animation.

In 1888 Étienne-Jules ‘E.J.’ Marey nearly invented movies, with high-speed sixty-images-per-second research into moving images. But it was William Friese-Greene who came up with the concept of perforations along the edge of filmstock, an idea later retrieved by Thomas Edison, who publicly demonstrated his peephole ‘kinetoscope’ viewer-device in New York, 14 April 1894. Then – in 28 December 1895, brothers Louis & Auguste Lumiére inaugurated the showing of moving-pictures in the dark of a Parisian café, graduating from brief naturalistic single-shot movies lasting less than a minute, including ‘L’Arrivée D’un Train à La Ciotat’ which shows a train arriving at a passenger station. It’s said that that the first-night audience fled the café in terror, fearing they’d be mangled by the ‘approaching’ train.

The Lumiére’s considered it a form of education. Wrong.

A professional conjurer and magician by the name of Georges Méliès was at the brother’s historic first screening, and he was quick to spot its potential. If the Lumiére’s photographed the world as it was, and didn’t forsee a mass-future for their technology, Méliès became so obsessed that he made-over his theatre into a picture-palace, devised his own studio and set about reconfiguring himself into a prolific producer of fantasy films, pioneering Special Effects techniques that merged live-action with dream sequences, using time-lapse, dissolves and multiple exposures to create impressively playful Jules Vernian extravaganzas such as ‘A Trip To The Moon’ (1902) and ‘The Impossible Voyage’ (1904).

But from the first moment there was moving film, since the illuminated projection of that first frame, there were nudes onscreen too, igniting a hundred-year war of attrition between suppression, and liberation. Méliès’ Star-Film company delved into the mild ‘stag’ market, with ‘Peeping Tom At The Seaside’, and ‘After The Ball’ in which actress Jeanne d’Alcy is bathed by her maid, although it’s fairly obvious she only strips down to a flesh-coloured leotard! Méliès’ vision only failed when his business collapsed during the ravages of the Great War. In despair he destroyed almost all trace of his work and vanished from history, only to be rediscovered many years later working in a Montparnasse toyshop, when his films were restored as iconic treasures of silent cinema. But elsewhere, the Lumiére brothers had scarcely secured a patent for their cinematograph before ardent monsieurs and mademoiselles were cavorting in Parisian boudoirs for hand-cranked cameras. French cinematographers first produced a short stag-film – ‘Le Coucher De La Mariée’ (‘Bedtime For The Bride’), as early as 1896, a slow striptease produced by Eugène Pirou and directed by Albert Kirchner under the pseudonym ‘Léar’. It was followed by the more visually ambitious 1928 ‘Messe Noire’ (‘Black Mass’), adding delicious blasphemy to the writhing bodies, mild flagellation and the initiation of a willing neophyte into a libertine Satanist cult.

In April 1896 Thomas Edison’s Vitascope launched movies-USA with a dozen filmed shorts intended to accompany live acts in a vaudeville theatre. From there the burgeoning New York film industry dramatically uprooted and crossed the continent before the outbreak of the First World War, to put down deep and enduring roots in California. It was real-estate men in the twenties who erected the familiar ‘Hollywoodland Hills’ sign, to publicise their new housing development. The last four letters of the sign’s first word would only be removed when the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce assumed ownership in the fifties. But by 1932 it had already become a symbol of lost dreams when – according to Dory Previn’s song “Mary C Brown & The Hollywood Sign” ‘she jumped from the letter ‘H’ ‘cos she didn’t become a star, she died in less than a minute-and-a-half, she looked a bit like Hedy Lamarr.’ In reality, it was the fate of young, British-born starlet, Peg Entwistle, who suicided in that manner after her failed marriage to character actor Robert Keith, and a series of filmic-flops.

By contrast, the real Hedy Lamarr became a massive star. Born Hedwig Keisler in Vienna, she began her movie career by skinny-dipping in Gustav Machatý’s Czech-made ‘Extase’ (1933), glimpsed as an elusive nymph naked in a dappled glade. Later in the film, her facial expressions suggesting orgasm were enough to be denounced by Pope Pious XI, while Machatý was promptly signed up by RKO in recognition of his innovative cinematography. Throughout the thirties and forties Lamarr was a sophisticate celebrated as one of the most beautiful Hollywood screen-icons. The Walt Disney studio modelled their ‘Snow White’ on her, just as replicant Rachel in ‘Blade Runner’ (1982) would be modelled on her. Although Hedy died a lonely death, ravaged by time and monstrous plastic surgery, almost a century after her naked beauty was captured in ‘Extase’, we can still admire those film inserts on YouTube.

Hollywood has seldom been interested in minority viewing. It seeks the mainstream, where megabucks assemble to be harvested. If the filmmaker’s primary concern – according to John Boorman, is ‘turning money into light,’ the new moguls instinct was exactly the opposite, to make huge amounts of money from images carved in light. The conundrum was how to tap into the mass-audience’s latent prurience while also getting around the inconvenient obstacle of social prudery? A useful strategy was devised through the convenient guise of ‘exploitation films’, the earliest of them sensationalising revelations from the Rockerfeller Commission report into prostitution and white slavery. Universal Studios released the silent ‘Traffic In Souls’ (1913, aka ‘While New York Sleeps’), ‘A Powerful Photo-Drama Of Today’ which was not only approved by the New York censor, but became a massive hit.

Adept at having it both ways, the ‘former U.S. Government investigator’ Samuel H London simultaneously bigged-up his own morally-uplifting role by founding ‘The Moral Features Film Company’ in order to produce his own ‘The Inside Of The White Slave Traffic’ (1913), with posters graphically showing a respectable young woman about to be accosted by a pimp. Inevitably the film proved another box-office hit. Such duplicity, exploiting seediness by supposedly advocating redeeming moral values, set the tone for what followed. Of course, words are subjective. They take on different meanings within different contexts. Their ambiguity is ripe for manipulative interpretation. During a vindictive separation, Charlie Chaplin’s second wife – Lita Grey, who had worked with Chaplin as a twelve-year-old ‘flirtatious angel’ in ‘The Kid’ (1921), accused him of ‘abnormal, unnatural, perverted and degenerate sexual desire.’ Her description conjurs all manner of unspecific abominations in the way that moral crusaders have always denounced works by employing equally evocative but unspecific trigger-words. It seems she was merely referring to oral sex. No big deal. Like beauty, filth lies in the eye of the beholder.

It was the Movie girls of the 1920s and 1930s who provide the high-profile mirror of sweeping between-the-wars changes. To some – as in James Thurber and E.B. White’s celebrated 1929 treatise ‘Is Sex Necessary?’, the essentially natural balance between male and female first became skewed when flappers began aspiring to equality by smoking, drinking, working, and imagining they have ‘the right to be sexual.’ Seldom overtly taking sides, Hollywood images shoved this dialogue onscreen by evolving their representation of the cutely comical kitten-sexiness of Mack Sennett’s romping beach girls into Marlene Dietrich’s smoky, sultry cabaret siren. Seductresses Veronica Lake took it further, then the one and only Rita Hayworth who ‘gave good face’ (according to Madonna), and the vamp-style bedroom-gowned tease of Harlow, Jean, ‘picture of a beauty queen.’ Her platinum blonde tresses achieved by bleaching her hair and rinsing it with methylene blue to create the desired effect, causing peroxide sales to zoom by thirty-five percent! But ‘they had style they had grace’ in a star-roster that ran from ‘oomph girl’ Ann Sheridan who had ‘a certain indefinable something that commands male interest,’ Carole Lombard – a graduate of the ‘Sennett Bathing Beauties’, and ‘sweater girl’ Lana Turner. While Vaudeville strippers Gypsy Rose Lee and Ann Corio formed one end of a spectrum contrasting the all-American wholesomness of Paulette Goddard, Dorothy Lamour, and Esther Williams. Beneath such high-profile productions, but sometimes filmed after-hours on the same sets, there are tales of explicit stag-films, such as ‘The Casting Couch’ (1923) showing a young Joan Crawford in a minor role as seductive wannabe ‘Gloria’.

With censorship at best muddled, outside the Hollywood village those devious foreigners were further testing the limits of what was deemed permissible. Germaine Dulac’s modest little 1928 film ‘Le Coquille Et Le Clergyman’ was refused a certificate by the British Board of Film Censors because, as one of its examiners observed, ‘this film is so cryptic as to be meaningless. If there is a meaning, it is doubtless objectionable.’ Exactly the same argument would be used to impose an American mid-sixties radio-ban on the Kingsmen single “Louie Louie” – that because the words were incomprehensible, they must therefore be obscene. The mild lesbian undertones of the erotically charged ‘Madchen In Uniform’ (1931), determined it would provoke the ire of censors everywhere. Directed by Austrian actress Leontyne Sagan – a protégé of Max Reinhardt, it was set in an authoritarian Potsdam all-girls boarding school, where it portrays a juvenile crush on the only Teacher prepared to challenge the school’s oppressive system. The incoming Nazis banned the film outright, they correctly identified it as a political rather than a sexual metaphor.

But then – before things could get totally out of control, as puritan protest groups ‘The League Of Civic Purity’ and the ‘Lord’s Day Alliance’ began picketing movie-theatres and editorials launched attacks on the corrupt debauchery of a Hollywood that was intent on undermining the moral values of young America, a thin-faced dour-looking Republican tee-totaller called William Harrison Hays was brought in to ‘clean-up the pictures.’ His Motion Picture Production Code became mandatory from 1 July 1934, but would be effectively enforced until 1967. Subsequently known as the ‘Hays Code’ it operated on ‘the law of compensating values,’ so that the only excuse for portraying ‘deviant’ behaviour was to act as a moral rebuke, that ‘if you sin, you must pay for it.’ It was largely a face-saving operation convened in the wake of the much-publicised trials of comedy-actor Roscoe ‘Fatty’ Arbuckle, unjustly charged with the rape and murder of a girl at a Prohibition-era drinks party, although subsequently vindicated he paid the price in that his career never recovered.

The first cycle of classic Hollywood gangster movies ended when Hays Office censors clamped down on the representation of what Robert Warshow’s celebrated 1948 essay termed “The Gangster As Tragic Hero”. The censors insisted that the FBI should be the heroes. When it came to the portrayal of sexual morality, it led to married couples discretely sleeping in separate single beds. And if couples happened to share a bed – under whatever pretext, they must always lie above the covers, with one foot still firmly placed upon the floor. It’s said that the code even disallowed the word ‘cock’ – as in ‘weathercock’, which has to be rendered ‘weather-rooster’. Maybe the story is apocryphal? because I’ve yet to find the movie-sequence where they actually say ‘weather-rooster’! Oddly, the first major instance of Production Code censorship concerned ‘Tarzan & His Mate’ (1934), a jungle romp in which brief nude scenes were edited out of the film’s master negative, although they didn’t show screen-‘mate’ actress Maureen O’Sullivan, but her body double!

Even cute cartoon flapper Betty Boop was induced to change her coyly seductive image, and began wearing old-fashioned housewife skirts. Although before, and indeed – after the imposition of Hollywood’s moral guidelines, movie-makers and their publicists simply got on with the game of playing cat-and-mouse with the censor. Independent films produced outside the mainstream studio system managed to escape censorial interference and flout the code’s conventions with films such as ‘Child Bride’ (1938), which features a nude ‘skinny-dipping’ scene involving twelve-year-old actress Shirley Mills. Others bypassed the code by touring circus-style in tents with bench-seats, screening different versions of the film as the threat of arrest ebbed and flowed. So that the films were shown with or without the risky bits, and there was a legitimising ‘square-up’ reel shown as a closer, which might contain either a moral lecture or, perhaps, a striptease, if conditions allow.

Dwain Esper (1892-1982) was known as the ‘King of the Celluloid Gypsies’ for touring his daring films and devising what must have been the ultimate combination of moral warning and sensationalism by displaying the preserved cadaver of ‘Elmer the Dope Fiend’ at screenings of his ‘Narcotic’ – although it turned out to be the body of a highwayman purchased from a passing circus. Among quintessential and now hugely-collectible movie-posters are those for Esper’s 1938 film ‘Human Wreckage’ which show a recumbent, scantily-clad young woman, with the straplines ‘A Timely Warning To Parents Of Today’, ‘Sex Ignorance’, ‘It Shows And Tells ALL’, and emphatically ‘Adults Only!’

The lurid movie-posters in the foyer of your local flea-pit, as well as the eye-grabbing glass-fronted display-cabinets outside, were efficiently promoting exposés of the seamy side of sex, drugs, and violence, promising much more than they ever actually delivered, while pretending to deplore it all anyway. ‘The Vice Racket’ (1936) claimed it ‘blasts the truth before your eyes.’ In accordance with the ‘if you sin, you pay’ morality, the duplicity of exploitation is seductive, drawing on the menace of immigration and miscegenation (in the U.S.A.), vice-ridden cities, white slavery, unmarried motherhood, sexually transmitted disease, marijuana, teenage delinquency, beatniks, nudism and wanton women, as well as rape by giant gorillas!

Ironically produced by a campaigning church group in Los Angeles, ‘Protect your Family: Know the Whole Truth’ screamed the foyer posters for ‘The Burning Question’ (1936), a film that warned ‘See… Innocent Youth Victims of Narcotics!’ Show-biz ‘bible’ ‘Variety’ magazine estimated that during the twelve months between 1932 and 1933, no less than 352 out of 440 movies featured ‘some sex slant’, with the hint of female flesh as a persistently consistent ingredient. Of course, the modern liberalisation of sexual attitudes has made such blatant tease redundant… hasn’t it? Well – perhaps not!

The mainstream was also nudging the limits, finding almost imperceptible ways of catering to the lubricious fantasies and erotic daydreams of audiences seated in darkened movie-theatres. Jane Russell found herself locked into a seven-year contract as protégé to obsessively eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes, and was caught up in a famous case of enforcement concerning the western ‘The Outlaw’. It was denied a certificate of approval and kept out of theatres for years because the film’s advertising focused particular attention on ‘Mean! Moody! Magnificent!’ Jane Russell’s spectacularly enhanced bust-line. ‘In my more than ten years of critical examination of motion pictures, I have never seen anything quite so unacceptable as the shots of the breasts of the character of Rio (Russell),’ censor Joseph Ignatius Breen reported to Hays, ‘throughout almost half the picture, the girl’s breasts, which are quite large and prominent, are shockingly emphasized, and in almost every instance are very substantially uncovered.’

Although the initial script was based around the Billy The Kid legend, publicity went to great lengths to showcase Jane’s voluptuous figure, stills show the ‘earthy moll’ lounging in the hay or bending over to pick up bales, ensuring her breasts are fetishised, lit, photographed, and designed to be dreamed about. According to long-standing mythology she wore a specially designed cantilevered underwire bra for the shots – the first of its kind. Hughes had it constructed according to aerodynamic principles especially for the film. She denied the story in her 1988 autobiography, claiming she was given the bra, decided it had a mediocre fit, and wore her own on set instead, merely pulling the straps down. Completed in 1941, the censorship problems concerning the way her ample cleavage was displayed meant it was only granted a limited showing, and it was not until 1946 that Hughes eventually persuaded Breen that her breasts did not violate the code and the film was finally passed for general release. But although Russell was kept busy during the intervening dates doing publicity and achieving fame, the experience making her savvy about the vulgarity of the movie industry. Besides thousands of quips from radio comedians, including Bob Hope who once introduced her as ‘the two and only Jane Russell,’ the photo of her on a haystack glowering with sulky beauty and youthful sensuality, her breasts pushed forcefully up against her bodice, became ubiquitous pin-ups for servicemen during World War II.

Together with Lana Turner and Rita Hayworth, Jane personified the sensuously contoured ‘sweater girl’ look, though her 38D-24-36 measurements and 5’7 height made her more statuesque than her contemporaries. She was the belle idéal of the war years. Not forgetting Betty Grable whose shapely legs – her renowned ‘gams’, helped bolster the wartime morale of Allied troops. But if the main function of photos and facsimiles of girls is to provide fulfilment when the real thing is out of reach, then the mass mobilisation of servicemen, with barrack-room time on their hands provided undreamed-of marketing opportunities for smut-peddlers.

And sure-enough the Girlies’ Golden Age begins in the 1940s, with fan-mags during WW2 as the prime vehicle for distributing official pin-ups to servicemen. War accelerated the great upsurge in girlie interest, with publishers cynically formulating the bright idea that lonely soldiers starved of ‘swell babes’ just might respond to images of healthy, well-bathed morale-boosting, smiling sexy chics. Hell, it was almost a patriotic duty! Dozens of new magazine launches reached the calloused hands and bloodshot eyes of servicemen. Capitalising on their propaganda-potential the U.S. Armed Forces even launched its own contender – the perhaps unfortunately entendrè-prone titled ‘Yank’, which contained regular, though fairly subdued pin-up features of fun-loving and wholesome girls. Yet each issue of the magazine was passed around until it literally fell apart. With photo-spreads ripped from the staples and pinned to barrack-walls, recreation rooms, toilets, aeroplanes, tanks – and, of course, lockers. In a sobering thought, it could have been me in an earlier lifetime, or you in an earlier lifetime, trying to somehow fasten those teasing pin-up pictures to the crumbling walls of some benighted muddy foxholes.

Thus we have the true origin of the pin-up. It soon became such an all-embracing term that it referred not only to the picture but to the girl herself. She becomes a ‘pin-up girl’, then simply a ‘pin-up’. Every man’s magazine worth its cover-price used the term liberally, for it guaranteed a seismic boost in sales. When salacious readers spot covers blaring ‘Pinup Reviews’, ‘Pinup Models’, ‘Pinup Poses’, ‘Pinup Parade’, and just about ‘Pin-up’ anything, they furtively sidle to the pulp mags to get their quota of fresh peeks at the latest dream girlies. Many of the publications leech from Hollywood studio-system PR stills. Few aspirant starlets with half-decent curves managed to escape unphotographed, unpublished while at least partially undraped. In fact, 1940s magazines would included any attractive female – from the discreet charms of the fashion-plate model to the up-front stripper with attitude, who could be beguiled into enticing a burgeoning readership. Millions of copies sold every month through both military and civilian outlets. And those names tell us a lot about the spirit and mood of the time – ‘Wink’, ‘Cutie’, ‘Nifty Titter’, ‘Flirt’, ‘Grin’, ‘Spot’, ‘Hit’, ‘Whisper’, ‘See’, ‘Eyeful’, ‘Click’, ‘Picture-Wise’, ‘Snap’, ‘Burlesk’, ‘Giggles’, ‘Tid-Bits Of Beauty’, ‘Showgirls’, and ‘Glamorous Models’. A few of them show nothing but girlies. And if, as Dorothy Parker quips, ‘brevity is the soul of lingerie,’ then here’s all the evidence you need. Others make it a point of covering social events, crime, sports and entertainment – on the principle of ‘the law of compensating values,’ all of which predictably feature their own share of attractive cuties.

There’s always been a mischievously subversive element to smut. Where mainstream publishers fear to tread, there’s always some do-it-yourself enterprise to supply its grubby needs. Hence the fly-by-night phenomenon of the so-called ‘Tijuana Bibles’, that had little to do with Mexico, and less to do with the gospels. From around the 1920s, but surviving through to more or less the 1950s, and especially in America, these crudely juvenile hand-drawn cheaply reproduced eight-page comic-strips were swopped and circulated through army barracks, naval establishments, bars, factories, in fact anywhere men gathered to bond. They were probably knocked-off secretly after-hours in print-rooms while the foreman’s back was turned. Maybe in batches as low as twenty, but picked up, copied, and done again in the next city under similar circumstances. Anonymous, often pirating copyrighted material in salacious ways, they formed a covert currency simply for the hell of it. Some names survive.

Wesley Morse is celebrated for his ‘World’s Fair’ series. But art credibility was seldom an issue. Anyone who could adequately caricature Popeye & Olive Oyl, or Dagwood & Blondie, add exaggerated sex-organs and show them in energetic action, would qualify. Movie stars were also targets. Others invented their own fantasy worlds, ‘Phil Fumble’ and ‘Iva Snatch’, ‘Pete The Tramp’ or ‘Schnozzle’, in self-contained cartoon exploits such as ‘She Ate A World’s Fair Hot-Dog, And Loved It’, or ‘A Sailor Finds Out If It’s True What They Say About Chinese Girls’. They survive in spirit as the photocopied sketches passed around the office, and later exchanged across the internet. While for those addicts overly concerned about the physical side-effects of such dubious reading material the May 1933 issue of the ‘Wonder Stories’ SF magazine carried an ad for the discretely mail-order-only manual ‘Sexual Truths’ edited by William J Robinson MD PhD – his impressive medical credentials providing legitimacy for chapters on troubling problems such as ‘Sexual Abstinence And Masturbation’ for those not actually doing it, and ‘Prostitution And Infection’ for those who were.

In England the modestly pocket-sized (A5) ‘The Man’ billed itself patriotically as the ‘Empire Magazine For Men’. The two-colour – black-and-orange cover of the April 1942 issue teases with a cartoon French maid propositioned by a lecherous roué. Her employer? She’s out. But ‘Me? Oh, I’m through at eleven.’ He smirks lasciviously beneath his neat moustache. And – despite the fiction and poems within, the cartoon content is by far the magazine’s most flirtatious element. An artist with a nude model signs the bottom corner of a huge blank canvas, ‘I’ll fill in the details some other time.’ A Spiv signs up for the Navy, ‘now, whom do I see about the Sweetheart in every port?’ – this is wartime, but the grammar (‘whom’) remains intact. There’s a ‘We Want Men’ Army recruitment poster, with a caricature geeky spinster brandishing a ‘Me Too’ placard.

While the prose features are sadly defensive, ‘Have We Still Two Sexes’ decries against women-in-trousers. There’s a sense that the gender balance of the world is changing in ways that these ‘Men of Empire’ find threateningly disturbing. Women are intended to be decorative creations who wear as little as possible – but trousers? out-BLOODY-rageous! So these men hide themselves within the comforting confines of their virtual magazine Club where ‘a widely experienced husband,’ the almost-certainly pseudonymous Gilbert Anstruther advises ‘How To Treat, Train, And Trim A Wife.’ Presumably – hopefully, the feature was intended to be tongue-in-cheek? his ‘Let ‘Em Have It’ treat-’em-mean keep-’em-keen theme is illustrated by a man spanking his wife with a strap, and another of him striking her with his belt. Ho-bloody-ho!

Yet even a decade later the long-running ‘Men Only’ still arrived in a discrete digest-size format of dense text pages, its fiction and features broken up by ironically-comic poems as well as shades-of-grey photo-inserts of sensibly-swimsuited ‘glamour models’. It was not alone. Although other competing titles – such as ‘The Standard’, were scarcely more racy, even though it did feature artistically-draped photo-spreads of posed ‘tableau’. ‘In olden days a glimpse of stocking was looked on as something shocking, now heaven knows – anything goes’ comments Cole Porter’s satirical contemporary Pop song. But not quite anything. No Split Beaver Shots. No Open Crotch Shots. Not yet. At least – not among the issues sold above the counter.

But for those who want movement? First there were the flickering images viewed through the ‘Penny Peeps’, the binocular ‘What The Butler Saw’ Arcade crank-handle machines. And then there were ‘Stag Movies’ with names like ‘Frisky Feathers’ or ‘Wiggle Mad’ – illegally filmed well beyond what the Hollywood Hays Code allowed, duplicated and illicitly circulated underground films for strictly male viewing in smoky clubs. Sweet Little T&A movies. Tits and Ass.

And Striptease was hardly a novelty – even since Salome. The amazing Josephine Baker took 1920s Paris by storm. Gypsy Rose Lee – played by Natalie Wood in her eventual Hollywood biopic, captivated America with more tease than strip. While fan-dancing Phyllis Dixey illuminated wartime London. The Minsky Brothers promoted their burgeoning U.S. Burlesque theatre chain, and used it to push the envelope – despite tasselated ‘pasties’ to cover ‘offensive’ nipples, until 1937 when the vigilance of New York Mayor Fiorello Henry La Guardia closed down Burlesque-houses as part of his anti-corruption drive. Flame-haired Tempest Storm – who later claimed ‘we were artists’, eventually took her striptease celebrity all the way to the Presidency, by grabbing John F Kennedy’s priaptic eye during a show at the ‘Casino Royale Theatre’ in Washington, enthusing how ‘he was almost insatiable in bed.’ The President also bedded rival Super-Star Stripper Blaze Starr during his trip to New Orleans in 1960, and had sex with her – in a wardrobe! Magazine crossovers proved a natural extension, with Munro look-alike Las Vegas stripper Dixie Evans as the cover-star of the July 1955 issue of ‘Bare’.

John Bratby was born in 1928 – the year of the Radclyffe Hall trial. By the early-1950s he was a prominent part of the ‘New Realist’ school of art, the ‘kitchen sink’ reaction to the then-dominant Abstraction. He would eventually die in 1992, a figure honoured by the establishment he frequently derided. But… backtracking a little, that would place his adolescence around the early-to-mid 1940s, a couple of decades before I was around. But – reading the series of autobiographical confessions he wrote for ‘Knave’ around 1974, I recognise many of the situations.

‘The first ‘erotic’ works that I read were ‘No Orchids For Miss Blandish’ (1939) by James Hadley Chase, and the last chapter about the reverie of Penelope in James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’ (1922)’ he recalls. ‘By the Kingston-on-Thames cattle market, there was a little sidestreet in which was a dirty bookshop, with a french-letter machine by the side of the doorway. To me, as a schoolboy, this was the red light area of Kingston, though there was nothing more – no whores or brothels, just a dirty bookshop and a french-letter machine. The shop was put out of bounds to the school eventually, because the old art master found a boy reading a book from the shop. Inside the shop, there was a hard-faced woman of about thirty, who always dressed in a black leather coat reaching to her calves. I quickly moved on from ‘No Orchids For Miss Blandish’. And bought ‘Nudes Of All Nations’, a photographic collection in book-form, pretending to be a serious work on anthropology. I went home on the bus with it, secreted against my jerseyed chest underneath my raincoat. But before I took it home, I walked with it through crowded Kingston, my heart pounding, till I reached the gates of Home Park, on the familiar grass of which I devoured the contents of the book. Would there ever come the day, could it ever arrive, when my moist young hands would hold breasts? Would I ever kiss a naked female body? It was all beyond my wildest dreams…’

‘Esquire’ – ‘Man At His Best’, was launched in 1933 under the editorial direction of Arnold Gingrich. But it found immediate success when mass distributed to WW2 servicemen attracted by the presence of its regular ‘Petty Girl’ feature. George Petty, the artist responsible, took advantage of his popularity by escalating his contract demands until – by 1940, management was searching for a cheaper more malleable replacement, and it wasn’t long before they signed the unknown and financially desperate Alberto Vargas. In his first art-contract with ‘Esquire’, Vargas innocently signed away his copyrights, allowing the magazine to promote the ‘Varga Girl’, miss-spelling his name for supposedly typographical clarity, but thereby allowing ‘Esquire’ to later claim legal rights over the ‘concept and creation’ of its registered property. Nevertheless the partnership proved initially amicable, mutually rewarding, and provided a career launchpad for Vargas to go on to work for MGM producing highly-collectable movie poster.

Between October 1940 and December 1941 the ‘Petty Girl’ and the ‘Varga Girl’ appear simultaneously in ‘Esquire’. And there are superficial resemblances for the less discerning, both present gorgeous females drawn in warm flesh colours and strikingly evocative poses. But where the ‘Petty Girl’ is streamlined to near-abstraction, her ‘Varga’ rival is super-real, bursting with vigour, allure, charm, humour, seduction, and eye-boggling curves. Long before silicon implants, bee-stung collagen-enhanced pouts, liposuction and all-over studio-tans they are there, setting impossible standards of fantasy beauty that no mere flesh-&-blood girl could ever equal. Her skin so taut-stretched over her body that surely she must burst like a balloon if that pin-up tin-tack to were to inadvertently puncture her flawless curves! To dramatise her popularity it’s only necessary to observe her success as a calendar pin-up. In December 1940 – a mere two months after her debut, she starred in her first mail-order only ‘Esquire 1941’ calendar. Garnering an impressive 320,000 sales, which had grown to nearly three-million by the 1946 edition.

The ‘Varga Girl’ did encounter some setbacks on the road to immortality. In 1943 the U.S. Mail challenged her fourth-class postal privileges – which granted cheap mailing rates to printed material of a ‘literary, artistic… nature.’ ‘Esquire’ was able to defend itself against this attempted censorship by proving in court that it performed a public service by advancing its suggestive, but non-prurient pictures in the context of a broad-based socially redeemable man’s journal. ‘Esquire’ rose to the occasion by marshalling key witnesses from what were deemed respectable professions – clergy, psychiatry and the universities, while government witnesses tended to be drawn from an unco-ordinated rabble of the anti-sex crusading heads of women’s organisations. ‘Esquire’ and the ‘Varga Girl’ were acquitted. As with the Penguin ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’ trial which ushered in the era of 1960s permissiveness, or the ‘Oz Schoolkids Issue’ at the Old Bailey which did the same for the 1970s, the courts’ findings made publishing history by finding no evidence of ‘lewd and lascivious’ material. It was shoving the envelope of what was deemed acceptable, and establishing a new benchmark for all the up-market girlie-mags to come. Erotic pics could not only be acceptable, but even respectable if they were included as part of a package that also contained a healthy balance of non-sexual visual or textual material.

In its final years as a soft-core contender ‘Esquire’ magazine attempted a number of alternative approaches to female portrayal – photographing ‘Esquire Girls’ in fashion features with models draped in sheer diaphanous fabrics or the ‘Lady Fair’ series showing famous but classy actresses in luke-warm portraiture. But little in ‘Esquire’s girlie realm could equal the erotic impact of Vargas’ improbable beauties – handcrafted dolls eliciting dreams and fantasies for a supposedly tasteful, erudite readership. Indeed, a Varga Girl appears on the cover-collage that Pop-artist Peter Blake assembled for the Beatles ‘Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band’ album.

Much later, when it was celebrating its Golden Anniversary with a December 1983 ‘Collectors Issue’ profiling Fifty American Originals – Alfred Kinsey: The Patron Saint Of Sex ‘who opened the door to let sex out into the sunlight,’ a Jack Kerouac essay by Ken Kesey, Jackson Pollock by Kurt Vonnegut, Richard Nixon by Gore Vidal, Neil Armstrong, Muhammad Ali, and Elvis, the magazine’s smut-pedalling origins were long forgotten. While even more recently, ‘Esquire’ got to celebrity-interview Osama bin Laden in 2001. Yet, ‘with its history of eccentricity, eclecticism, and downright quirkiness, (it) stands as a monument to the durability and constant evolution of the different,’ even taking editorial time out to recall ‘when sex was a big deal and Petty’s and Varga’s slim art-deco girls (were) food for thought.’

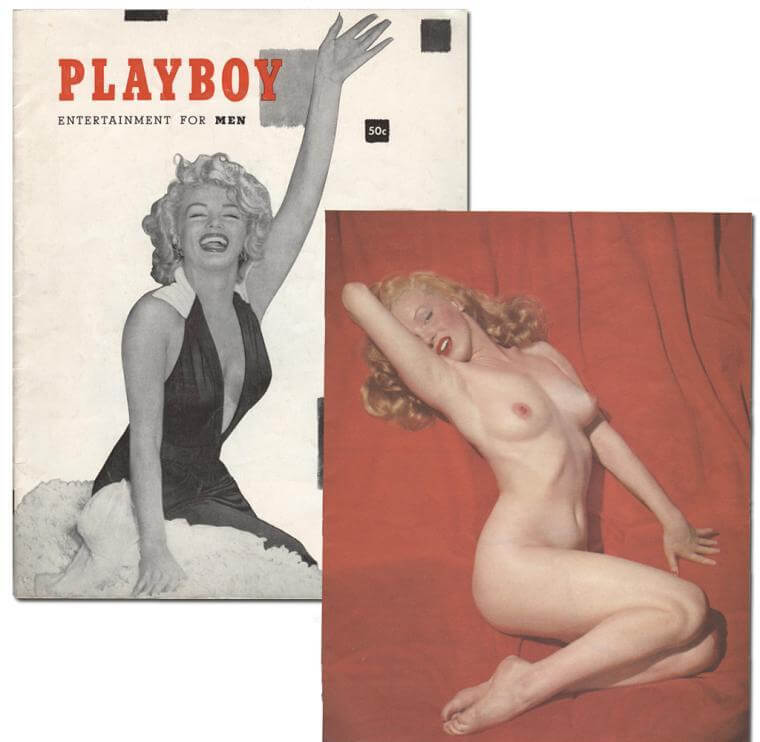

Yet – the conscious editorial decision to withdraw from the girlie market as the final ‘Lady Fair’ graced ‘Esquire’ in 1956, might just have had something to do with the new and all-too formidable New-Kid-On-The-Block competition starting up just a few years earlier. The ‘Esquire’ issue dated September 1951 featured a high-profile Marilyn Monroe fold-out centre-spread pin-up. She was the blonde that gentlemen of the period preferred, who exploded through pervasive 1950s drabness like a peroxide hydrogen bomb. The photos reveal her generous cleavage, but unlike the rival’s spread – no nipples or nudity. ‘Playboy’ had arrived in no uncertain terms to move things along a little further. In issue no.1 that same Marilyn is also featured… wearing nothing more than Chanel no.5.

Meanwhile, back on the silver screen, Deborah Kerr’s career took a major upturn when she played Karen Holmes, the bored wife of a brutal company commander in Fred Zinnemann’s ‘From Here To Eternity’ (1953). ‘I feel naked without my tiara’ she joked while being fitted with the revealing black bathing suit she was to wear in her iconic roll in the waves with her lover, the decent Sgt Milt Warden (Burt Lancaster). The erotic sequence had been considerably toned down from the way James Jones wrote it in his original 859-page novel, but its Honolulu Oahu’s Halona Cove beach near Diamond Head film-location has subsequently become a major destination for tourist coaches. She persuaded censors and audiences alike that adultery could be permissible, morally justified, and she got away with it because she played – as Zinnemann said, ‘ladies who had what Hollywood called ‘class’.’

BY ANDREW DARLINGTON