“To pass through pain and not know it

car door slamming in the night

To emerge on an invisible terrain”

—from John Ashbery’s “A Wave”

“Like the mass on a spring in the animation at the right, a

vibrating object is moving over the same path over the course

of time. Its motion repeats itself over and over again…. The

time it takes to complete one back-and-forth cycle is always

the same amount of time.”

—from The Physics Classroom

PART 6: Y = F(-X)

-1.

You, nor anyone else, actually lies in the road bleeding. Yet you are in the road, really in the road, it’s just that you, personally, have never actually been there. You think you have, and you can still see the blood on your hands as the sky shines elsewhere, the water rising, catching itself on the lowest branch, rising into the clouds, rain finally cleaning away your presence, which is merely a reflection that appears and disappears as we conceive of you, imagining us after the dust cleans the lens looking down on the old and lumpy chair in which you sit, believing you are still the hill you have always thought yourself to be, the roads around you actually leading us to think of you as the glass shatters into the front seat and the smallest of wings slice through you through us. It never occurs to you there is a back seat. You do remember someone mentioning it. That it is especially nice for couples in the evenings when the sun sets. That babies are often there in little seats staring out the window. You are like that baby now. Everything happening to you for the first time, simply appearing as in a mirror, shining back, in reverse.

-1.

Now that you are merely the thoughts of a landscape, you think carefully, ideas arise you never considered letting anyone in on, like the reason to preserve the seams of a horizon you sew together for us to have a straight line on which to return. None of your ducks are lining up as you thought, and only a tiny aspect of us now tries to find the pocket into which you fold each memory of a sky looking back at the leaves falling when the wind decided to stop, when the moon stayed even though you walked away from a story you throw back at yourself whenever you need a moon, a story everyone, inside their own moon, tells themself to drag back the tide to step into the story each of us fails to remember.

-1.

You never guess we are on the opposite side. Never against you, always against you. You might suspect this to be the case. We give you hints, intermittently, but all the same, easily seen by anyone who cares to look. Evidently, you never do, or can’t, it all depends on what side of the coin you stamp your hopes to find us. You seem to want your efforts taken for granted, which we do, and now, sitting where you sit, unable to reach us, a sad place rests, looks after you. You never dreamed of being so alone. Each breath you take tries to find us, still, you reach for the sky you haven’t seen for years, ever really, because the air you breathe is only in your dreams; we know this because our soft touch is still ahead of you. Never mind what comes; the penny you lay on the tracks is for later; for now, you lean forward; the rest of you arrives after we leave, after you pull back your shoulders, stand straight, look ahead at what follows; the space between us stops short of the time allowed for time for you to appear, to keep yourself as yourself, who you might become.

-1.

Your poetry will never reach as far as the wave, but you and only you evolved to a story told by a distant tree growing alone in the sea, its roots grabbing onto the receding shore the moon of night and day pull towards you. And you, your own branches holding onto the tiny claws of a blackbird, looking while being watched, spreading the thin mist of your beginning and your end, as you begin again for the last time. This is a matter of reflection, a state not to be confused with looking inside the bowl in which you understand what and which is being poured into you; it’s a state of understanding light and dark, reaching you as the shadows on the walls slowly crumbling, thin layers of your flesh laid across the narrative that has, forever, written itself quietly outside your comprehension, because, in the depths of your grief, what needs to be told belongs to us, a story we tell with great caution because of how difficult it is to withstand so much disappointment, because the story of regret can only be told to those of us who feel regret, an imperative for any form of decency, which, at last count, has slipped through so many fingers there is now a shortage of hands.

-1.

You decide to take a stand. Right before our eyes. If we can, we will help you to the corner of your hill you are last seen. After that, you’re on your own. Keep a light step as all of us nearby hope to find you off guard, vulnerable to the light we leave behind each time we disappear. The catch to which you are accustomed each evening depends on the swells each day as well as the time it takes you to sail into the beds of kelp that feed you. Eidetic by most standards, but always behind the scenes spilling over the sides you can and cannot see, your only wish now is for someone to follow you up and over, bringing the moments that prove you are still here and why. Turn off the lights; let the ants discover the crumbs on the floor. Prepare your sponge; wipe away all you can and cannot see. You remember exactly what happened that night, where you might have been and why you seem to still be there.

-1.

In the shade each thought spreads, you leave behind each reason to set things straight, leave behind the same reason you continue to walk into thin air, the reason stars vanish or an instance occurs. In the time it takes to turn your head, the water left behind dries beneath your eyes. You start the wind, try to believe in someone else, perhaps detect the breath that follows.

For now it is make-believe, as if, while listening for the moment each of us returns, every step lifts the seconds in which we predict how you appear and disappear, how you come up for air, descend into dark waters. As you turn off our lights, we turn the corner. You are here, sitting on the side of the road waiting to cross. You are here, sitting in the front seat. You are here, your antlers brushing against your trees, brushing against any trace of you. When we find you, we check each other’s wounds. If either of us walk away, the trees follow. Then the elk. Then the meadow. Then the hill. The last time we see you, we ask for something of yours to carry us through. It is easy to forget each other. Thankfully, there are places each of us know to find the other after dark. Where the wind dies down. Where we left our scent.

As the left side of reason lights up like a Christmas tree

On Robert Lundquist’s Mass: A short essay by Ithamar Handelman-Smith

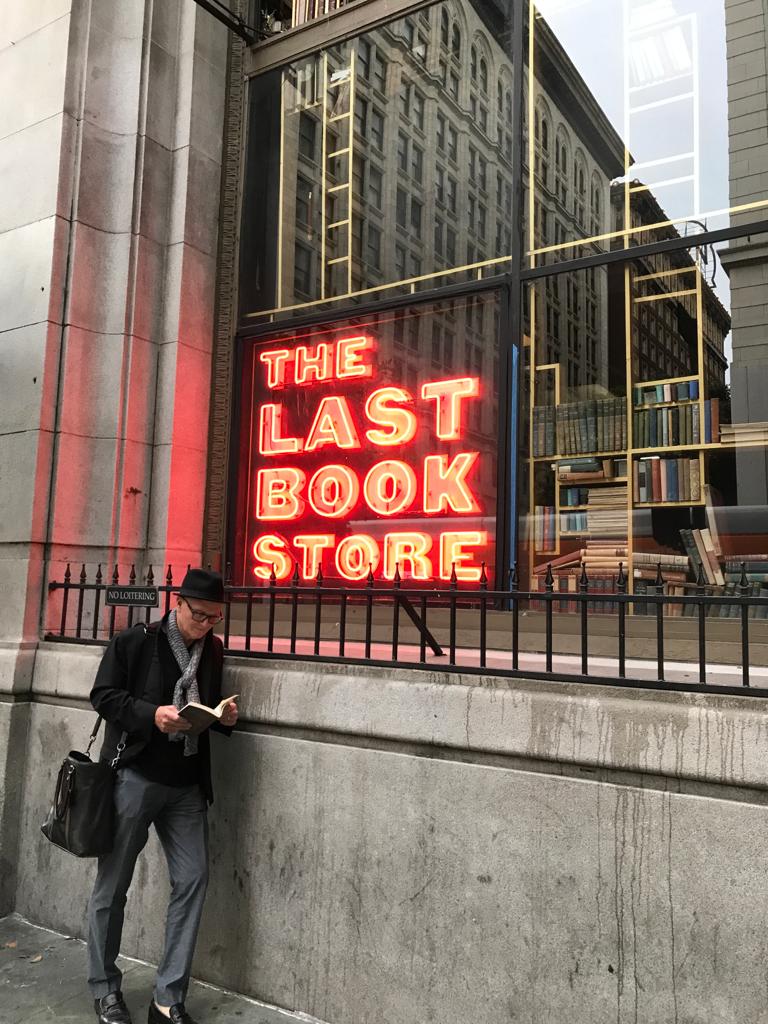

Though only known in Europe now, Robert Lundquist is still one of the last great American poets.

Like all great American writers, Lundquist’s poetry is entwined with his biography. A native of Los Angeles, his father was an LAPD undercover cop and his mother survived tuberculosis at Barlow’s Sanitarium. At a very young age, he spent part of his time with his parents in Alhambra and part of the time with his grandparents in downtown LA, especially with his grandmother who worked as a waitress in Union Station.

His unique life journey echoes that of his contemporaries in the Santa Cruz poetry scene of the 1970’s and of other major figures in the West Coast literary circles, from beat generation poets to Raymond Carver and Charles Bukowski. But, where many great American artists fall in the abyss that lies between essence and content, Lundquist did not fall.

The reason for his long-standing relevance lies within his consisting ability to change form and style in response to changes in his private life. While the sombre realism of his previous book, After Mozart (Heroin on 5th St), coincides with his own life experiences of living behind garages and battles with the demons of alcoholism and addiction, (He did travel back and forth to LA, scored on skid row, made a lot of “friends” there but managed to stay out of homelessness

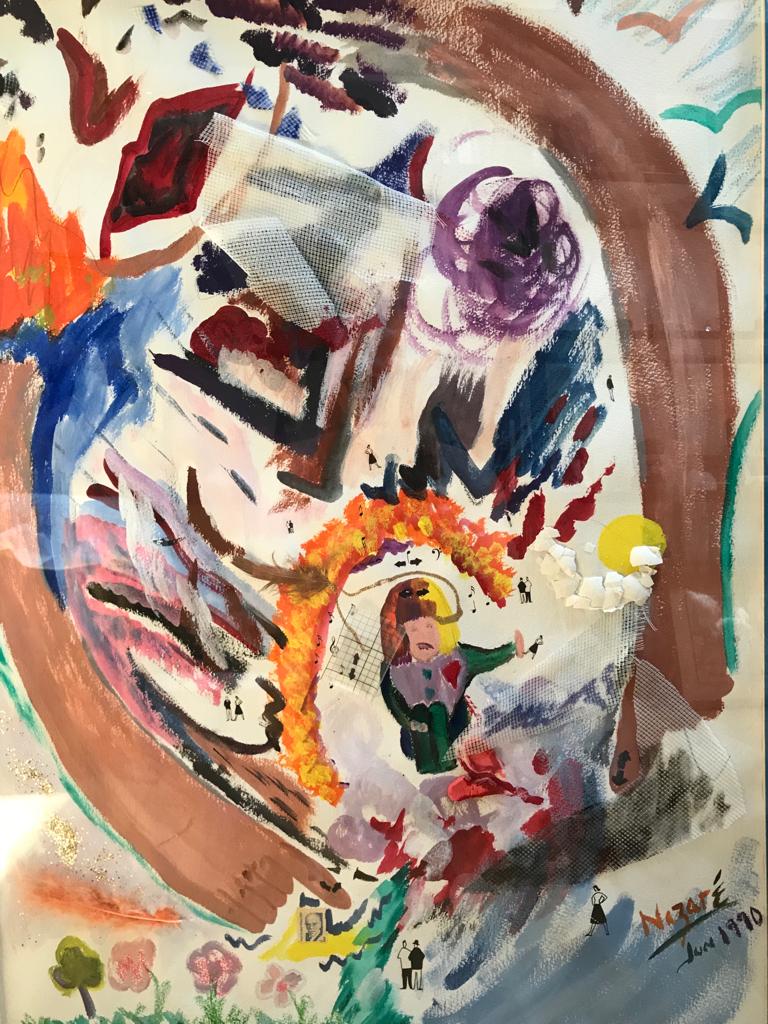

His new poems (collected under the title of Mass), reflect the spirit of his later life as a psychoanalyst. When referring to his new material, Lundquist himself disagrees with the label ‘poems’ altogether. He refers to his new collection as a series of ‘texts’. In a way, he is right; these are not exactly poems. They are indeed short texts and they read like poetic vignettes. But while the world of his previous collection of poems had dark, subliminal urban currents, the world created in his new collection shifts between that old dark world where You try knitting together the blood remaining, you learn about the tar that takes away your pain, the world of streets filled with homeless and junkies where You learn which streets, covered with tents, sell you the tar with which to dream, and a new path: There are those of us who argue that the streets fill with tents so the elk can find us, show us the water running through you.

If in After Mozart the option of healing nature existed only as a failed promise or a forgotten opportunity, Mass offers something different, something new. It is not the case that the poems of After Mozart lacked spirituality, which opened with the dark magic of Oh our majesty who condemns us all, but the spirituality of Mass lies elsewhere.

The texts of Mass, and in particular the lyricism of the fifth section, Y= F (X), are immersed in the ideas of Quantum Physics and their relation to the art of psychoanalysis. This is complex and yet beautifully simple at the same time. The spiritual idea that mind and emotion influence reality, a reality in which we, and everything around us, are electrons that moves in and out of some mysterious Quantum field, are weaved like in a medieval tapestry throughout the beautiful, enigmatic vignettes of Y=F (X) and Mass as a whole. But Lundquist is not a preacher and he does not force feed the reader with those ideas.

On the contrary the power Robert Lundquist’s short texts is in the things that are not said, or – in the words of Harold Bloom – what we call a poem is mostly what is not there on the page. The strength of any poem is the poems that it has managed to exclude.

IH-S, 2022