|

Keith Rodway

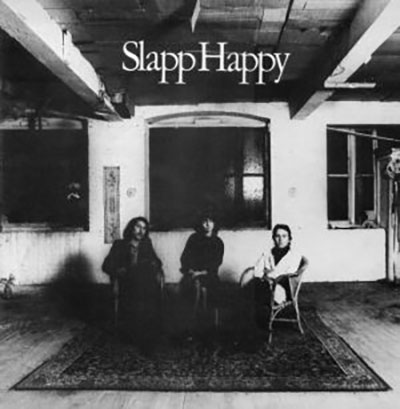

I first became aware of Anthony Moore when I bought Slapp Happy’s eponymous album on Virgin Records in 1974, a recording sandwiched between earlier collaborations with German avant-rockers Faust and later with Brit-prog outfit Henry Cow. Slapp Happy’s pan-European whimsy, fronted by German singer Dagmar Krause, was a welcome relief from the torpor of mainstream acts such as Eric Clapton, Bad Company and Fleetwood Mac. It is an album I still find intriguing almost 50 years later.

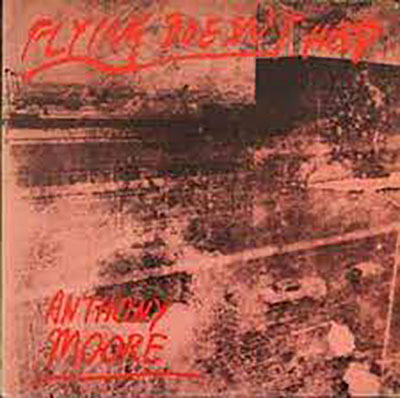

Moore then released an excellent post-punk solo album, Flying Doesn’t Help, in 1979. Then, for me, the lines went dead. I only discovered recently that there was a second solo album, World Service, in 1981. Moore acted as lyricist on a handful of songs for David Gilmore’s Pink Floyd albums, A Momentary Lapse of Reason and The Division Bell, wrote No Parlez for Paul Young and collaborated with such stylistically disparate acts as Julian Lennon, Trevor Rabin and Kevin Ayers. Slapp Happy released a highly recommended reunion album, Ca Va, in 1988.

In addition to all this Moore has released several albums of experimental music along the way and enjoyed a 20-year tenure as Professor for Musik at the Klang Geräusch Academy of Arts Cologne, Teaching Theory and History of Sound.

In 2019 I learned from my friend Simon Charterton that Moore had moved to my home town of St Leonards. He and I have since been occasional guest performers in Charterton’s alt groove band Simon and the Pope.

On the eve of his appearance at a Club Integral night at Iklektik in Waterloo on March 10th, I caught up with Anthony Moore at his home in St Leonards.

KR:What are your earliest memories of exposure to music?

AM: My grandmother’s voluminous contralto – a great big wobbling jelly of sound to my 2 year old ears – and making crystal sets in the 50s, Bakelite headphones… followed later, thanks to my father’s peripatetic journeying, by the squawks of short wave transistor radio, BBC world service’s Lilliburlero – we lived in Cyprus in the 50’s and Africa in the very early 60s (that means the airwaves were flooded by Arabic, Turkish, Armenian, Greek and African music too).

When did you realise that music was going to be your life? Did you

try any other occupation?

A brief stint at art school in St Albans and Newcastle (yes, I’m another bleeding 60s art-school drop-out), but growing up in the 60s meant it was always going to be music. With that insouciance of 60s youth I never considered another job – being prepared to crash on floors, have no sense of the future and being ridiculously self-centred.

When did you first work on scores for experimental films? How did this come about?

The first filmscore was for David Larcher’s “Mare’s Tail” – 150 minutes of non-narrative and extremely poetic imagery. But there was no ‘score’ as such. With the small budget we decided to purchase a number of old tape recorders, Brenells, Ferrographs, an early Nagra… This allowed me to multitrack, overdub, loop, splice, change speed and pitch and reverse sound material that was sourced

from field recordings, old upright piano frames, penny whistles, what have you. The crucial point being that with ribbons of magnetic tape you find yourself as a musician using the identical techniques that experimental film makers applied to ribbons of

celluloid. The connection between image and sound is therefore established through the technology and how you use it rather than through any ‘mickey mousing’ or illustration of the image.

What were the connections between Faust and Slapp Happy?

Uwe Nettelbeck. He had discovered the seedling Faust, installed them in a small country school house somewhere North of Hamburg and built them an 8 track recording studio to live and play in. Uwe also edited a well-known magazine called ‘Filmkritik’. By 1969 I was living in Hamburg and making the soundtracks for a number of underground movies which got shown in various festivals. Uwe saw these

films, was into the music that accompanied them and got me a deal with Polygram to record 3 LPs – “Pieces From The Cloudland Ballroom”, “Secrets of The Blue Bag” and “Reed, Whistles & Sticks”. These were all minimalist, instrumental works and on their completion he asked if I might be prepared to make an album of songs. I contacted Peter Blegvad and having met Dagmar Krause, Slapp Happy was born. We went up to Wumme where Faust were living and working, and as we had no rhythm section of our own it was a happy and natural marriage with the Faust gang that allowed us to make two Slapp Happy LPs in their studio. Later in 1972 both bands signed up with Virgin Records.

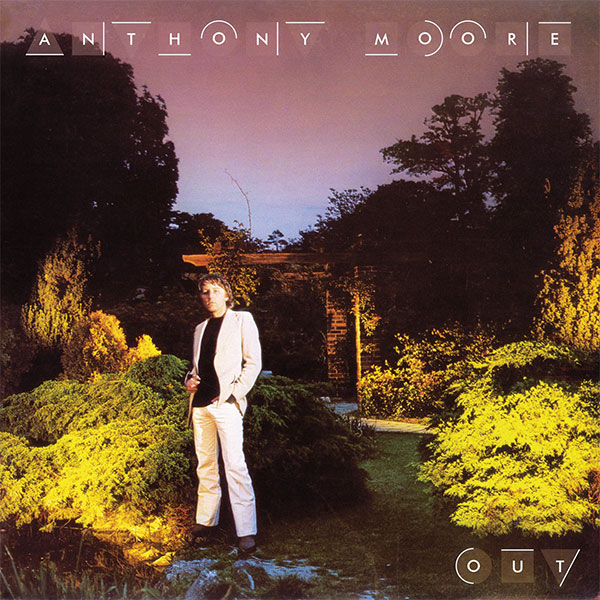

You were unceremoniously dumped by Virgin Records just prior to the

original release date for Out, in the mid 1970s [Out is available now on Drag City or via Bandcamp]. How and why did this come about?

It’s a mystery, frankly. The LP was already finished and mastered; even the artwork was complete – a cover designed by Storm at Hipgnosis. It was 1975/6. The lawyers and accountants were moving into the music business – I guess I was too weird for them… or at least lacked a sufficiently focused and aggressive ambition to be commercially successful. Oh well…

What is your understanding of the basic principles of experimental music, and what role or function does it play or serve?

I think, however naive it might seem, freedom in a broad sense has a lot to do with it: a rejection of conformity: an ego-less acceptance of chance and to be unafraid to fail. There is also a satisfying if reactionary joy in confounding those same

‘accountants and lawyers’ just referred to. They (the principles) may also make no sense; but I have always thought that nonsense is what separates us from the animals.

You’ve worked on a number of projects involving other artists across

a variety of genres, and in different roles, as lyricist, producer, and

so on. Which for you was the most intriguing and/or most baffling?

I probably take collaborating with others too seriously. I like to work to deadlines and I do find it useful to feel under some kind of obligation; to have to keep promises. It’s very helpful in the unframed drift of my daily weekly monthly yearly life.

Unsurprisingly, the most intriguing is the unpredictable, the live work, performing; most baffling, and it’s why I don’t do it so much anymore, is the grind of writing.

You worked for a number of years teaching at the Academy of the Arts

in Cologne. How do you think this might have compared to a similar role here in the UK?

I landed an unbelievably fortunate position in Cologne. I was handed the outrageous freedom to teach what I didn’t know. This allowed the opening up of new horizons for me personally, and the golden opportunity to learn with diverse and exceptional students about myriad things in the realm of sound, music and noise; not least its ancient history, its connection to technology and society, to mathematics and physics, and to art – 20 years of pure adventure! I don’t think that could have happened anywhere else. The only minor downside was a slight lacuna in the output of my own material. But there were advantages to this too, as I mention later.

Electronics in music have gone from being a marginal force in music in the

mid 20th century to occupying a significant place in the current

mainstream. What do you think are the triumphs and what are the

drawbacks in respect of this? What has been gained and what has been

lost?

I can’t really answer this as I am not sure what constitutes ‘mainstream’ and ‘electronics’. It would be easier for me to at least put forward my personal view on the effect of ‘accountants and lawyers’ on the nature of songwriting. I sorely miss the

inventiveness of Brian Wilson and The Beatles… but that’s just an old bloke moaning, probably.

What projects are you currently working on?

Prior to Cologne which ran from 1995 to 2015, I saw myself very much as a studio animal crawling around the floors of windowless rooms with half a dozen patch cables round my neck – happy as a pig in the proverbial. I loved machines, especially tape recorders. Whilst I ceased making much of my own music in Cologne it nevertheless presented me with an unexpected plus. Pontificating in

lectures, conferences and workshops pretty much weekly got me out of the windowless rooms with their engines of production, and into the world of live performance, i.e. teaching. As a consequence, what I am doing these days is grabbing every opportunity to get up and make a fool of myself in public. It’s a great privilege to start a new chapter at the end of the book.

https://reflectionsonsound.bandcamp.com/

Could you please let us know when you are appearing anywhere as we would like to come and see you ? Thankyou Anthony

Comment by Ebdon Flode on 17 January, 2026 at 1:26 am