Overview of:

‘WILLIE NELSON: AMERICAN ICON’

(Sterling) www.sterlingpublishing.com

ISBN 978-1-4549-2619-1 Large format hardcover 208pp

In an earlier but equally divided America, Willie Nelson proved the only icon capable of bridging its social chasms, outlaw enough to appeal to the long-hair counter-culture, but trad country enough to have written “Crazy” for Patsy Cline. Of three versions of “Always On My Mind” it was not the classic Elvis post-Priscilla or the Pet Shop Boys electro-Pop version that scores highest on the Billboard chart, but the sprawling languorous Willie Nelson version. Why? Because Willie is a good ole boy, and everyone loves Willie. When the Byrds arrived in Nashville to record ‘Sweethearts Of The Rodeo’ (1968), when Dylan teamed up with rugged legend Johnny Cash for ‘Nashville Skyline’ (1969), or for those to whom the ‘Hotel California’ was too slickly air-conditioned, they found Willie already there. Already an upsetter with ‘a gypsy heart and a maverick spirit.’

To journalist Andrew Vaughan who first met Nelson accidentally when he wandered backstage at the 1988 Wembley Arena Country Music Festival, he’s a ‘genuine hero of the people’. He and his songs firmly grounded within the country mainstream, while rebelling against the Nashville business culture as the reluctant figurehead of a Texas country-rock ‘movement’ that grew around him, and centred on Austin. As Vaughan phrases it, Willie was ‘a struggling songwriter whose inner faith refused to allow himself to be eaten up by the uncaring music business in Nashville.’ Mapping both a back-to-basics rediscovery of roots, and a forward into new undiluted Americana frontiers.

Born on 30 March 1933 in Depression-era small-town Abbott, Fort Worth, of English-Irish descent, Willie was mostly reared by his god-fearing paternal grandparents following his parents split. The first song he learned to play was Ernest Tubb’s “Walkin’ The Floor Over You”, strumming along to the radio on his cheap Sears Roebuck mail-order guitar. At sixteen he joined older sister Bobbie in the Texans group, playing local dances. Later, he sold vacuum cleaners, became a tree-trimmer, nightclub bouncer, dishwasher at ‘Aunt Martha’s Pancake House’, an auto-parts worker and door-to-door encyclopaedia salesman. But he was also doing radio spots and DJ-ing, moonlighting writing and selling songs on the cheap to pay bills for his cash-strapped new family. He played as a band member with Ray Price’s Cherokee Cowboys while writing major hits such as “Night Life” (for Ray Price), “Family Bible” (a 1960 hit for Claude Gray), “Hello Walls” – ‘a classic ode to loneliness’ (for Faron Young) and “Funny How Time Slips Away” (for Texas-born Billy Walker). As a time-fix, at the time the tragic Patsy Cline was taking his “Crazy” to no.9 on the US ‘Billboard’ chart – November 1961, the Beatles were still a name unknown outside of Liverpool, yet to make their failed Decca audition.

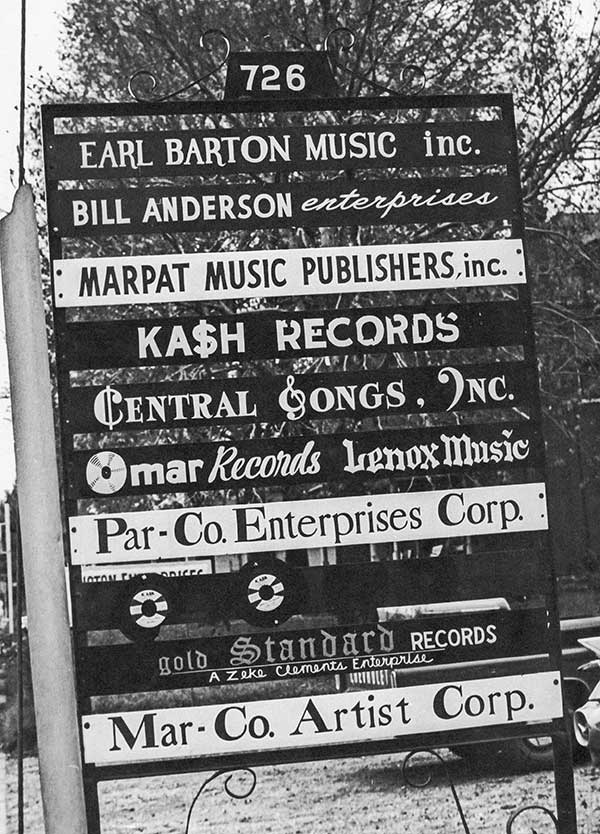

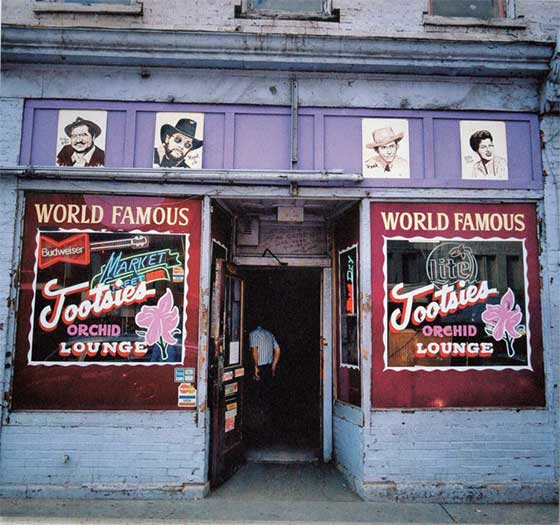

Heading for Nashville in a beat-up 1946 Buick Willie soon made connections, hanging out with others on the make, such as Mel Tillis, Kris Kristofferson and Roger Miller at ‘Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge’, a honky-tonk adjacent to the Ryman Auditorium. But Music City’s response to Rock ‘n’ Roll had been the syrupy orchestrated New Country of Don Gibson, Jim Reeves and Faron Young, a sophistication at odds with Willie’s raw sensibilities. Nevertheless, having previously recorded for small independent labels Betty, Houston’s D Records, and Bellaire, his writing success snared him a 1962 Liberty deal. Debut album ‘And Then I Wrote’ (September 1962), featuring just Willie and future second-wife Shirley Collie with producer Joe Allison, yields a country hit with “Touch Me”. Half-talking the title across a jog-along backing, the voice is instantly recognisable, even if the slick smartly-suited cover-shot visage is less familiar. His voice is unique. But the writing is vital. There are lots of distinctive voices. They need songs.

Sometimes the songs he writes are maudlin, sentimental. Willie wrote “Pretty Paper” which aims for every tear-jerk reaction in the canon – Christmas, a down-and-out peddler of cheap festive trash. Yet the demo gets picked up by Roy Orbison, no mean writer himself. I disliked its calculated saccharine overkill, but it climbs to no.6 in the ‘New Musical Express’ chart for 12 December 1964, beneath the Beatles “I Feel Fine”. Willie has the instinct for touching hearts.

Is the original always best? Not necessarily. Willie’s half-talking reading of his own “Funny How Time Slips Away” tells the narrative with aching sensitivity, a conversational phone-call to his former lover, addressing her directly, even asking after her new love. Elvis takes the song for his 1970 ‘Elvis Country’ album, and projects it more powerfully. Al Green takes it slower, lighter, in a soft soul setting. Joe Hinton personalises it into my favourite version, treating it as a deep soul ballad, rising into piercing falsetto. Bryan Ferry makes it arch and mannered, all surfaces. Over at Motown, even the Supremes do a version. Which is the song’s real value. Its superficial simplicity touches and communicates something deep within the human experience, which lends itself to infinite interpretation across genres. The strength of country has always been just that, the ability to express profound everyday truths, in direct non-intellectual ways

But Willie’s hard-scrabble days were far from over. ‘Music City was not kind to musically opinionated non-conformists like himself (Willie) and Waylon (Jennings).’ He tries to play the Nashville game. Although he gets to open for Roger Miller at the ‘Grand Ole Opry’, his second album – ‘Here’s Willie’ (1963) bombs, and he label-switches to Monument. Then again to RCA in 1965, with the twelve Willie compositions on ‘The Party’s Over’ (1967), and highly-rated “Once More With Feeling” (from ‘Both Sides Now’, 1970). Already into his third marriage, spurred by a house-fire in his Ridgetop family home he quits the Nashville machine. Craving room to experiment and develop his more-than-usually complex off-the-beat phrasing and melody-lines – major chords and jazzy minor sevenths, within trad-country fare, he relocates to Austin, and to Atlantic Records. As a result, his sixteenth studio album ‘Shotgun Willie’ (Atlantic, June 1973), and ‘Phases And Stages’ (March 1974), recorded with Jerry Wexler at Muscle Shoals, are the bridging statements of his style, paving the way for his greatest commercial success, for Columbia the following year.

‘Red Headed Stranger’ (May 1975) provides the long-awaited breakthrough, spawning his cross-over hit cover of the Fred Rose song “Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain”, formerly done by Roy Acuff and Charley Pride. The loosely-connected theme of the fugitive on the run after killing his wife and her lover is matched to the defiantly sparse instrumentation, just dusty authentic voice and ‘Trigger’ – Willie’s sage-brush guitar. As country matures into Americana, the New Breed ‘Outlaw’ persona is now complete. Vaughan says that ‘he discovered the artist inside himself in the 1970s and went from the neatly coiffed and suited writer of good songs for others to the long-haired star of a new brand of music – all in the space of a few short months.’ Into the familiar bandana, beard and flame-red braids of ‘Shotgun Willie’. After years of Nashville frustration, of trying to conform, he’d found the freedom he needed.

Working on a furious album-a-year basis, at least one Willie-related long-player would chart each year for the next fourteen years. Binding himself into the community with the Farm Aid charity project, a vociferous advocate of reforming the marijuana laws – with a grand jury subpoena for drug violations to reaffirm his Outlaw credibility, he seldom conforms to expectations. At a ‘Long Horn Ballroom’ club date in Dallas during the segregation-integration flagellation, sensing unruly racist restlessness, Willie not only embraces African-American country singer Charley Pride on stage, but kisses him on the lips, which must have been as much of a shock to Charley as it was to the rednecks in the audience! In 1991 when he was nearly bankrupted by the tax system, Willie promptly records ‘The IRS Tapes’ (1992), and tours himself back into solvency.

Albums tend to be a mix of originals balanced by his slant on other people’s material. Even when the label has doubts, his instincts win out, and seldom prove false. As with ‘Stardust’ (1978) an easygoing collection of Great American Songbook titles that stays on the chart for two full years. Produced by Booker T Jones it includes a stripped-back reading of Hoagy Carmichael’s 1930 “Georgia On My Mind”, more recently a Pop-Soul hit for Ray Charles. Willie’s slow reflective tempo with keening harmonica rides it into the Pop chart too. Then he pays dues to country’s essential conservatism with his ‘To Lefty From Willie’ (1977), his tribute to the late Lefty Frizzell. And there are duet albums with Waylon Jennings (‘Waylon And Willie’ 1978), Leon Russell (‘One For The Road’, 1979), Kris Kristofferson (‘Willie Nelson Sings Kris Kristofferson’, 1979) and Emmylou Harris (the 1980 ‘Honeysuckle Rose’ soundtrack album). While ‘Wanted: The Outlaws’ (January 1976) gathers material by Waylon Jennings with wife Jessi Colter, Willie and Tompall Glaser, within an Old West-style sleeve, and it sells a million.

Now, Willie is a good ole boy, and everyone loves Willie. The Highwaymen, a kind of country Traveling Wilbury’s supergroup takes him through into the 1990s, through Western movies and into a fourth marriage. Across the millennial divide he’s Country Music royalty, moving from Island to Lost Highway records, spinning-off into reggae and Snoop Dog collaborations, before returning to the lodestone of his roots, as new and newer country generations swirl around him. He’s God’s Problem Child, the man who also write ‘Roll Me Up And Smoke Me When I Die’…’

With this richly-illustrated large-format volume Andrew Vaughan charts every vagary, in a detailed diary of the trip. There are stop-off points along the way, thumbnail sketches of those who influenced him – Hank Williams, Bob Wills, to those whose careers he influences – Patsy Cline, and milestone albums. Then detailed listings of albums, movies and a Willie Nelson bibliography.

Despite its expanding sprawl, the Nashville music centre retains an essentially small-town community feel. Where frighteningly-good buskers in Stetsons set up on the corner of Broadway and Second Ave performing their own highly-original songs, with a good chance that a label boss will stroll by on their way from ‘Boot Country’ to the ‘Wildhorse Saloon’. Where you can idle around the 16th 17th and 18th Avenue Music Row, by Chet Atkins Place or RCA Studio B off Roy Acuff Place. In Nashville they’re still proud of Taylor Swift, although she’s long-since moved out of country into the Pop mainstream. It was Willie Nelson’s unique ability to cross over without ever losing his roots. Even when recording with Julio Iglesias, he’s still Willie.

BY ANDREW DARLINGTON