The scene: a covid vaccination centre in Eastbourne. Summer 2021

I am in the queue for my first jab. An admin assistant is scrolling on her computer through the obligatory questionnaire.

Admin assistant (white female; early 40s; upbeat demeanour) (to me; cheerily): Are you happy to be described as White British?

Me (white male, 68 years old, laconic demeanour): No, I’m not

AA: (nervous laugh) No-one’s said that yet

Me (figuring not: this is, after all, Eastbourne. Bexhill is where ideas come to die. Eastbourne is where they end up afterwards): That doesn’t surprise me

AA: So…what should I put down?

Me: Northern European

She smiles. I can’t figure what exactly the smile signifies. She taps at the keyboard in front of her, the computer monitor screen angled towards her: I can’t see what she writes. White British male nutter? Early-onset gammon? TS BUNDY[1]? I have no idea. It doesn’t really matter. I’ve said my bit. We move on.

***

In September 2016 I registered at the School of Global Studies at the University of Sussex as a PhD student in visual anthropology. Prior to this, in 2005, I had been awarded a BA in English Language. In 2009 I graduated in an MA in Social Anthropology, and in 2012 an MA in Digital Documentary – all at Sussex.

The working title of my PhD thesis was No Kidding: Societal Attitudes to the Childfree. I chose this topic initially because my long-term life-partner had always maintained she didn’t want children. Nonetheless, around the age of 35, close friends began barracking her about her choices. Don’t be awkward, you know you want one really, you’ll change your mind[2], God gave you a woman’s body, why not use it – that sort of thing. For the next three years I scoured books, journals and newspaper articles – both online and offline – for as much information as I could find on the increasingly vibrant discussions in the media about women living in the West opting not to have children. I wanted to know what kinds of criticisms women other than my partner were subjected to because of this lifestyle choice, and what kinds of support they were given. In addition, I researched all the various, often bitter, arguments in academia regarding film as a tool for the collection of research data. Does film have the potential for the same degree of rigorous analysis as written text? Or is it just a cheap gimmick? Etc. After a year out due to financial difficulties, I submitted my research outline, detailing the understanding I had gained of the literature I had reviewed, plus my carefully-constructed argument in favour of using film as a research tool. The first draft was rejected. After a frantic weekend of tweaking and revising, I submitted again. A review by my peers declared it ‘excellent’. I was congratulated. (You can read it here on IT, via the links below). So, in theory, I was now able to crack on with my fieldwork – I could begin filming and writing: a 40-minute documentary-style film of interviews with close friends who I knew had unconventional attitudes towards parenthood, plus a 40,000-word written thesis. I was told that no other anthropologist had chosen to work with this topic – a good thing, I supposed.

So far, so good. But then…

Before one can begin one’s fieldwork one must complete an ethical review form. This is to ensure that one’s work will conform to certain ethical criteria, most of it common sense – in essence, one must not disparage, misrepresent or expose one’s respondents to the potential for any kind of harm, physical or psychological. I was told by one of my supervisors that it was merely procedural – that if any objections were raised, the review board was simply justifying its existence. It would be a breeze.

If only.

When writing a research outline in Social Anthropology you are required to give a breakdown of the kinds of questions you will ask the people you interview. This I did. My questions were formulated according to the arguments I had researched in the literature, both historical and contemporary, for and against choosing not become a parent. The major part of it was negative. (A recent commercial for Crown Paints (Crown Paints Hannah and Dave on youtube) received 150 complaints for its negative portrayal of a woman who has become pregnant after years of saying ‘no way’ to having kids: this supports the common assumption that women who say they don’t want kids are just being awkward, and they know they will give in in the end. It also cracks a lame joke about the prospective dad only hoping the child is his. Not only is the mum an awkward cow, she’s also likely been sleeping around).

So my questions reflected such societal attitudes. That was the brief I gave myself – to see how the friends I wanted to interview had dealt with this kind of stuff during their lives. I knew that they would be quite capable of understanding that the questions reflected negative social attitudes out there in the various spheres of discourse: that they didn’t reflect my own mindset on this. Moreover, they would have grown accustomed to sticking up for themselves and answering back when they were accused of being selfish, ‘unnatural’ women (or men) who only cared about themselves, with no concern for the future generations whose potential for existence they were denying. They were and are highly intelligent, self-determined, articulate people who know their minds, and know how to handle themselves in the face of verbal opposition. Their ages ranged at the time from 28 to 65.

So far all good.

Six weeks after I submitted my form to the Ethical Review Committee, I got my first response – ‘Returned for revision’. OK, I was expecting this – if they didn’t find something to bitch about, what was the point of having them? A lot of the stuff they wanted to see was about formatting – tick-boxes for questions, a couple of things added to the talent release form (if you take part in filmed interviews, you sign away your right to ask for anything to be changed or removed once the film is completed. You might have this choice at an earlier stage, but essentially it’s to prevent anyone trying to intervene after the final edits are made). One thing, however, puzzled me – I was asked how I could guarantee anonymity in the context of a film. Short answer – you can’t, unless the person speaking is off-camera, or is in silhouette, or has a bag over their head, and even then – depending on the context and the sensitivity of the data – you may be required to alter their voice. One of my arguments for using film was that you can see the person responding to your questions – by observing their facial expressions and body language you can be with them in the moment they answer the question. Yes, this can be rehearsed. Even so, you get a sense of the person you’re watching (particularly if they’re doing something else – driving, household chores like washing up, where their mind is not entirely focused on self-censorship as they speak), and it’s hard to argue with the idea that if you see and hear them speaking, and their lips apparently synch with their words, you can be reasonably certain that what you hear is what they said and that they themselves said it (now, however, with the arrival of AI deep-fake videos, this could notionally be contested). With written text there’s no such guarantee. You can make stuff up if you’re not getting the responses you want. I know this: I’ve done it in the past. I puzzled over the question of anonymity. What was I supposed to say? I said that no real names would be used, and no footage would reveal where they lived – no-one would be filmed opening their front door or driving down their street. I hoped that would do, while not really believing that it would, as it seemed like a question designed to trip me up, somehow or other.

Then, towards the end of 2020, the pandemic struck. I had to wait a year to re-submit my ethical form. Fifteen months later, in January of 2022, I got my second application returned. The question about anonymity was repeated, but this time there was a whole load of new stuff – why did I want to make a film? Why couldn’t I write a book? Why did I want to ask these questions? Why not focus on the positive aspects of not having children? If I was going to ask such questions, I must provide details of accredited therapists to treat my potentially traumatised respondents. And, the final indignity, ‘Please can you consider in your resubmission the possibility for any distress you may experience during this research and how you will deal with that should it occur.’

The simple answer to most of these questions was: read the research outline. I spent three years detailing the reasons I wanted to make a film and why my questions were intrinsically negatively loaded. Furthermore, my respondents were quite aware of the positive aspects of remaining childfree: that’s why they had made such choices. As to the suggestion that I needed a cohort of therapists to counsel my traumatised friends once I’d battered them senseless with my invasive and insensitive lines of questioning – what the fuck? And as to the idea that the whole thing was going to be so distressing that my mental health would suffer a result… Fuck you, and fuck your patronising bullshit.

I sensed immediately that the game was effectively up: I could argue my case via a third submission of the ethics review form, spending another term and another £700 in the process. Or I could read the signs in the prevailing wind, and withdraw. I withdrew from the University.

***

According to the August 10th 2022 edition of The Week, eight institutions, ‘including Russell Group members Warwick, Exeter and Glasgow, have made texts optional to protect students’ welfare’.

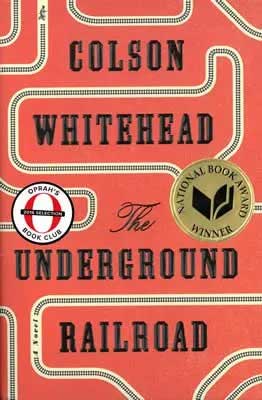

An article in The Times of April 21st, 2023, spoke about books being removed from University Libraries, one such being Sussex, on account of references to slavery and suicide potentially triggering students. One of these books was the Pullitzer Prize winning novel The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead.

The Week continues, ‘The paper sent almost 300 freedom of information requests to officials at universities across the UK, and uncovered 1,081 examples of trigger warnings across undergraduate courses. Influential British authors including William Shakespeare, Geoffrey Chaucer, Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë and Charles Dickens were reportedly among those whose works have been deemed concerning enough to require warnings.

‘The investigation also found that students had been given trigger warnings before studying The Bible, because of ‘shocking sexual violence’, and Oliver Twist, because of child abuse.

‘Other targeted texts include Swedish writer August Strindberg’s 1888 play Miss Julie, which has been axed from an undergraduate literature module at Sussex University because it contains discussion of suicide.’

***

A friend told me recently of all the stuff that her son, who is 15, has to deal with during a routine day at secondary school: gender identity issues – Am I a boy? Am I a girl? Somewhere in between? None of the above?; knife crime; porn; online and offline bullying and fat-shaming; body dismorphia and eating disorders, often due to #thinness posts on social media; conspiracy theories and radicalisation via far-right online chat groups; PTSD due to the recent global pandemic, the war in Ukraine and concerns about global heating; and not forgetting, of course, especially if you board at a private school, online and offline grooming and sexual abuse at the hands of predators (though this is not limited to schools as anywhere there are young people under supervision – church and sports groups, Scouts and Brownies, care homes, theatre and performance groups – to name a few – there are almost inevitably going to be adults with inappropriate sexual interest in young people.) So I am not unaware that young people have stuff to deal with that was unthinkable when I was at school (apart from the sexual abuse), much of it to do with the internet and social media. The effects of all this on the mental health of younger people is not to be underestimated. But Charles Dickens? Really? We must protect young adults from fictional accounts of child abuse, especially when it might be happening right under their noses in the present moment, often at the hands of a family friend or extended family member? Will it not be understood that Dickens wrote 150 years ago, that his works are historical accounts of a society long vanished? Or slavery? (Slavery existed: it’s a historical fact. It still exists now, and many young people might know this because they’ve been trafficked to the UK so older people – many of them from ‘respectable’ backgrounds – can have sex with them. Presumably they don’t end up at Russell Group Universities, so they don’t count.) And the Bible? Yes, it contains some weird shit (including the idea that a menstruating woman must leave the house while she is ‘unclean’, and that anyone who sits on furniture she has contaminated with her lack of cleanliness must leave the house, wash their clothes and not return till evening). While it might not be universally agreed that the Bible is largely a work of fiction, it’s clearly somewhat off its head. Is this a problem for younger people? (There’s an issue here: if one agrees that any of this is absurd, one could be identified as ‘anti-woke’. Liz Truss, Suella Braverman and Lee ‘Lee Anderthal Man’ Anderson are all famously anti-woke, and who wants to be seen agreeing with them?)

***

The reaction among members of my focus group was a mixture of bewilderment, disappointment, frustration and anger. ‘So, that’s that then? After all this time?’ asked one. To quote another: ‘Who the fuck do they think we are? This is patronising crap. We’re not poor little wilting snowflakes. We know how to think about issues affecting our lives.’ When I told another that I had been expected to arrange for professional counsellors to be on hand should I traumatise her, she laughed. Yet another remarked that ‘this shuts down nuance and freedom of speech. We don’t need the protection of some prat at the University of Sussex. It’s not just you that’s being patronised’ Well, yes, I think it does; no, I don’t suppose you do; and yes I agree. Others in my group said they’d been looking forward to answering the questions, as they reflected long-standing concerns they had lacked an opportunity to vocalise. Another told me that her daughter, aged 25, couldn’t afford to leave home because renting or buying her own property, even though she was earning a good salary at her workplace, was simply too expensive, and that as a result starting a family was simply not an option. And in any case, she and many of her friends simply had no interest in having children. Birth rates are falling across the world. The issue of child-freedom is increasingly becoming a much-discussed topic. My research would have given me the opportunity to address all of this.

And yet…

Two years after I withdrew from my degree, doubts have been accruing. In the immediate aftermath of receiving feedback from the Research Ethics Committee, with my pride damaged and the sense of humiliation and disappointment seeping like fresh wounds, I resolved to get my own back by writing a withering response here on IT. This article began as just that. But now, I find myself wondering if they might, on certain grounds, have been justified in their objections.

The world has changed in many significant respects since I first applied to do my PhD at Sussex. Younger sensibilities are driving the bus now. Most of the passengers will be in their early – mid 20s: the number of mature students in academia across the board has declined sharply in the last 20 years. Our views, our preoccupations, our approaches to life are considered anachronistic at best, and irrelevant at worst. The fact that we Boomers pride ourselves at having been at the cutting edge, 50 years ago, in fighting for many of the rights that are now taken for granted among younger people, is also irrelevant. There will be many levels of nuance that have accrued since people my age marched with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, for instance, back in the 1960s and 70s. Our first tentative steps to demand rights for gay and trans people, disabled people, civil rights for ethnic minorities; rights for animals, or whoever and whatever; or our attempts at combating racism, misogyny, sexism, homophobia, Islamophobia, xenophobia; the formation of Red Wedge, Stonewall, Rock Against Racism; the championing of vegetarianism and veganism; our anti-capitalist sympathies and activism – all will be seen as the fossilised steps of dinosaurs. Younger minds are at work, configuring responses according to their own experiences of the world, not merely continuing or expanding upon work done by previous generations. New conversations have arisen around gender – not just the age-old polarised divisions in society that the very notion of ‘gender’ represents, but far more subtle layers of discourse. Autism and neurodiversity are hot topics now, but these barely existed, or had failed to be recognised, in the past. The list goes on, the arguments become increasingly bitter and divisive, and right-wing invective in mainstream media fans and fuels these fires. Younger people reject such media: they look to podcasts, TikTok and YouTube content for news and comment. They have developed networks and working practices of their own. Regrettably, it is entirely plausible that I am indeed too old, too much a part of a quaint, largely vanished world to truly qualify for a place at the academic table in the current social climate.

***

After all this time I think back to the vaccination centre. Why did I mind self-identifying as White British? Not only do I not identify as such, but also I am reluctant at this particular time in history to identify as a white British male approaching old age with all that such classification implies or entails. I don’t want to be shut in the same enclosure as Piers Morgan, Lee Anderson, Jeremy Clarkson, Nigel Farage, Jacob Rees-Mogg, or any other passive-aggressive (or just plain aggressive) white British male gammon. I don’t share their views and I don’t appreciate their devaluing of the tag ‘male’, even whilst acknowledging that there are plenty of white British males who do not share their odious views. Nonetheless, there is the fact that I am white, British and male, and have recently celebrated my 70th birthday. Was that a factor in all this? Was I considered unsuitable to conduct my research on the basis of my age, ethnicity or gender, even given that any lack of my awareness of the precise terms of contemporary discourse around multiple issues was unconscious? Did it make me an ageing barbarian, pounding on the gates of the citadel, demanding the right to harangue long-term friends with my abrasive verbal assaults? Should I have written a happy-clappy self-help book about the joys of rejecting parenthood, the kind you might find in an esoteric bookshop off the Charing Cross Road, along with ‘wellness’ manuals, CBD products, dream-catchers and Angel Tarot decks? Is that the kind of academic rigour we now expect, and favour?

***

So, the thought police are alive and well and patrolling the halls of academia. Don’t worry, dear snowflakes, Sister Academia has your back. Who’d have thought it would come to this? Where do we go from here? Do we in fact ban books with ‘dangerous’ material from their libraries? What are the implications of such measures? Should we shield young people from references to harsh realities? (For me, the whole thing seems misjudged – so much online content that young people are exposed to day after day is way harsher than the works of Chaucer, Shakespeare or Charlotte Bronte. And then there’s the infantilising brain-rot that comes from reading J.K.Rowling, or watching the 67th Marvel movie…Should we not be shielding them from that?) Does it end there, or will there one day be surveillance apps which monitor your private conversations via your smart phones or Alexa or some such, and which report you to some authority in some facility somewhere for discussing toxic subjects, and endangering the mental health of others? Will you be hauled off to a re-educational facility? Is this the kind of neo-fascist authoritarianism we expect our university departments to sanction? It does make me concerned for the future just not of academic enquiry, but of our freedoms generally. Is being ‘woke’, i.e. insisting on inclusive representation across all divisions, fostering an awareness of, and contesting in the public arena, certain notionally anachronistic or antagonistic attitudes, and potentially barring those advocating them from the privileges of mainstream society – is all this a mandate to develop new dogmas, orthodoxies, or puritanical purges of our inner lives? Is it just me, or does the whole thing smack of something like religious conviction – the certainty that one is right, and anyone who disagrees is inherently in need of reorientation and rehabilitation?

A few questions at the end of all this remain. Am I entitled to wonder why the Ethics Review Committee failed to read my Research Outline, to get acquainted with my methodology, so they could see what I had planned to do, and why? Or did they read it but decided to press on anyway? Does the fact that the outline was judged ‘excellent’ by my peer reviewers have no part in all this, and if not, why? Why weren’t objections anticipated at a much earlier stage in the process, before I spent many years of my life and £6,000 chasing a phantom? What kinds of further sanctions are to be overtly or covertly placed on one’s academic freedoms, and at what future cost to the store of human knowledge?

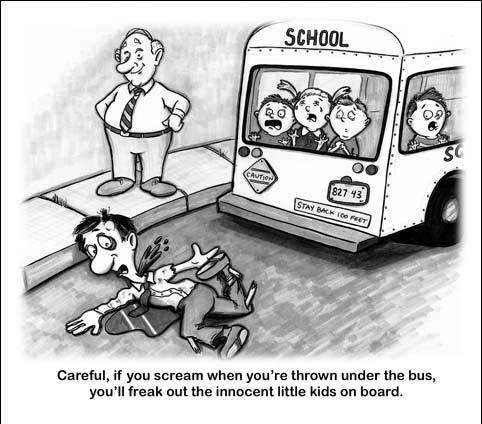

Could I have raised a complaint? Notionally, yes, but the outcome would almost certainly be that ranks would close; the University would protect its own. Like any corporate entity operating in an open market, reputational integrity is paramount, no matter what the cost to the end-user. The interests of the consumer – the mug who pays good money so these units can operate – are the least consideration. We are at the bottom of the food chain, gasping for air.

***

As to the question of anonymity, I eventually phoned the office of the Ethics Review Committee at Sussex. There I spoke to a cheery young man, who said, ‘Oh that’s easy. You add a clause to the release form saying they waive their right to anonymity.’ Oh ok, so it was a trick question then? You can’t guarantee anonymity for anyone you film, so you pass on the responsibility to them, you throw them under the bus, you make it their problem? If they get trolled or get death threats, they knew what they were letting themselves in for. Ok, cool.

As it happens, my two short-form documentaries (one of which was my final project for my MA in Digital Documentary at Sussex in 2012), about a friend who decided to undergo gender reassignment surgery, have had almost 32,000 hits between them on YouTube. I’ve had around a dozen negative comments (such as ‘surely some bestiality here…’ and ‘Sick Shit’, which I reported and which have been removed). No medical professionals were involved in this process.

***

During a class at Sussex sometime in 2003 the tutor announced, a propos of nothing anyone had said or asked, that the notion that academic standards were falling was entirely fallacious. No-one had questioned that, so why announce it?

During my final year as a lecturer at a university which had opened a campus locally, I raised the question with my ‘line-manager’ about the poor quality some of final assignment work that had been submitted. I was told not to worry about it, to give everyone 65%. A friend who until recently taught at a highly prestigious university in central London, almost exclusively to overseas students, raised concerns last year that he had about five of his class cohort: he suspected them of academic malpractice. Specifically, he doubted that they were the authors of work submitted. Whilst this is not the same as plagiarism – he hadn’t suspected they had copied another author’s work – it is certainly now a tricky issue. Either they had used AI to write the course work, or they had engaged the services of a professional essayist. He raised the alarm with the relevant authorities. He was told to let it go. Not long later his contract was terminated – he had presumably been identified as a potential trouble-maker and had been moved on.

What does this mean not just for academic standards, but for the future of academia generally? Since university tuition fees were raised in 2012 in the UK to £9,000 a year, higher education has become a global consumer product. For overseas students the fees are much higher as there is no cap on what institutions can charge. At prices like this, consumers can expect a product that reflects the expense. Failure is not an option. For overseas students an MA from a top university in the UK may be a status symbol, something for parents to brag about to their friends, or to impress clients should the recently-graduated young person enter the family business. My friend was unable to definitively verify that the work of five of his students was not original. To the institution, the fuss that would result clearly wasn’t worth the bother. The objective is to get the money, deliver the product and move on. If the students chose to use AI to generate their course-work, how was that to be policed? Did it really matter? As long as they went home with a qualification, surely the job was done? Maybe in the future students will use AI to write their work, the tutor will use AI to assess it, and everyone can go to the pub.

Had I continued with my research degree, how would all this have impacted on me? I have no idea. Ultimately, sadly, to withdraw was a relief for a variety of reasons. I do worry nonetheless about future generations of students. Once again though, we now live in a very strange world, one in which, due to a variety of factors, I feel I have become increasingly marginalised. The world changes and systems adapt. Maybe it’s not my problem; I shouldn’t give it another thought.

You can read my research outline here https://internationaltimes.it/no-kidding-societal-attitudes-to-the-childfree/

Keith Rodway

2nd Image MyDad by Anthony Browne

[1] A nurse friend once told me some of the acronyms doctors use when writing notes during a consultation, to describe the patient: PBM (Poor Biological Material), LMF (Lacking Moral Fibre), TS BUNDY (Totally Screwed But Unfortunately Not Dead Yet)

[2] There is now a youtube video discussing this very point https://youtu.be/zo7aw6TAjFg?si=x0wLjc5tEiqzPuFB

Excellent and thoughtful article Keith.

Comment by R on 16 March, 2024 at 9:11 amVery interesting, Keith. And depressing. When teaching MA students at Sussex, I was infuriated when an overseas student who plagiarised very substantially twice, was nevertheless awarded his degree. That was 2010. When I complained I was pretty well told to shut up. And let’s not talk about Kathleen Stock.

Comment by Barbara Allen, BA (Hons), PhD (Sussex) on 16 March, 2024 at 8:13 pmBrilliant article Keith. Covers so much so clearly. I started an MA in Philosophy of Religion and Ethics last year and quit after the 2nd term. I was re-entering academia after three decades and can relate to your disappointment and anger. I found that generational change and interaction with younger students really interesting but what appalled me was the actual quality of the course. I often seemed to be updating the reading lists with material that was more contemporary and relevant to the needs of the present, and there was a general sense of things just coasting along, avoiding being overly critical and reducing everything to formulaic arguments that could be easily marked. The admin and communication was a dreadful too apart from the finance department of course! At least I got a refund for the last term.

Comment by Valerie Grove on 17 March, 2024 at 9:59 amAn excellent if disturbing account of anti-academicism in UK academia. I think Keith Rodway should submit his article via an online complaints form to Sussex University (if it makes it through word count and stylistic policing). Everything Keith writes rings true, as you’d expect from an author with “lived experience” of his subject matter. This article should be sent to every university in the western (and some of the “eastern”) world. Small criticisms of his article could be made, such as the assessment of the Bible as essentially a work of fiction – a perspective that may well be correct but one rarely deployed by writers when it comes to other great monotheistic texts; and his use of the imprecise term “neo-fascist” as a label regarding constraint on speech, or indeed thought, when such constraint could equally imprecisely be labelled “neo-Communist” as opposed to the more objective and simple term “authoritarian” or even, arguably, “totalitarian”. Such quibbles aside, I was moved and angered by Keith’s no doubt not uncommon experience in “liberal” academia (label use and meaning meant ironically). I would hope that he can somehow find the time and motivation to conduct his academic research wholly under his own umbrella and then self publish it as a PDF to be sent to every social anthropology university department in the world and to his no doubt long list of friends and associates. Keith’s research topic and methods sound totally fascinating.

Comment by Neil Partrick on 17 March, 2024 at 10:22 amOne of the best rants I ever read. Disturbing, but also thought provoking. I have quite a few friends who have not had children, myself included, and it’s alarming and depressing that such women, yet again, can be so thoughtlessly maligned. The world’s population is exploding! I could go on… Well done Keith, for continuing with your project through such obstacles, maybe you can do the film yourself, without a university involvement.

Comment by Claire Lewis on 19 March, 2024 at 4:56 pmThank you Claire. At the moment I’ve decided to let the project go, as the whole Sussex Uni experience was dispiriting, sadly – but I may well take it up again in the future, as it’s clearly a topic that resonates with quite a few people. Thank you for comments..

Comment by Keith Rodway on 19 March, 2024 at 10:09 pmKeith, you’ve gotta get down with the hood man (i know, this vernacular belongs in the late 60s when i was 7yo) don’t you realise “Sick shit” means exceptionally good and cool?

Comment by Kendal on 31 March, 2024 at 7:44 amThanks Kendal. Clearly I’m even more out of touch than I’d realised. For a long time I thought ‘vibes’ meant Milt Jackson with the Modern Jazz Quartet. I really must try harder to get ‘down’ with the kids. Having said that, I do think in this case ‘sick shit’ meant sick shit, but I’d be up for being proved mistaken.

Comment by Keith Rodway on 1 April, 2024 at 10:41 am