Centre Pompidou, Paris – Ends October 3rd

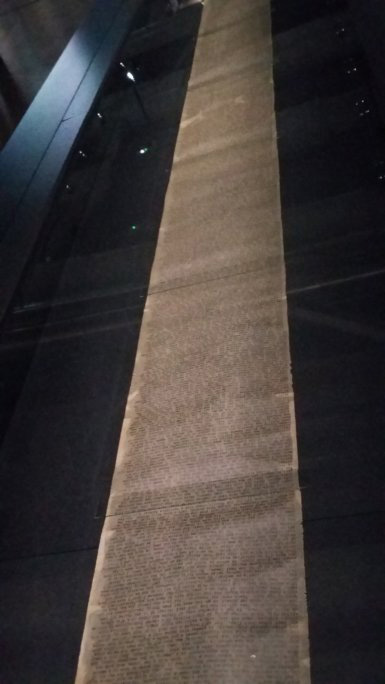

You enter a very wide & long space, bisected by a very long narrow cabinet, which starts about 10 metres from the entrance and stretches 40 metres, leaving about 10 metres at the other end of the room, where a film is projected on the monster screen of a wall. The cabinet houses the remains of the long scroll on which Kerouac typed a version of On The Road. The far end of the scroll was apparently eaten by someone’s dog. In the dim light, the paper, darkened with age, is almost unreadable. It is the unavoidable relic that visitors must walk around to get from one side of the exhibition to the other. High above the cabinet hang 3 screens, each showing a different part of an old black and white 15 minute film of country roads in America.

On either side of the scroll, the space is divided into a series of open-plan rooms. On the left of the scroll, the exhibition deals mainly with places, on the right mainly with people. A long wall on the left side bears a Kerouac quote : Everything belongs to me because I am poor.

Turning from the scroll back towards the entrance, 4 telephones with dials sit on a table. You are invited to “Dial A Poem”. Each number dialled gives a different poem, so there are 40 poems to listen to. Nearby is a chronology on the wall, the timeline of significant events in the Beat Generation. The walls are covered with black & white photos, sketches, drawings & paintings of or by the main actors – Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs, Corso, Rexroth, Neal Cassady, etc & a fair number of minor characters. Pull My Daisy, a halfhour film based on a collective poem, is showing in a darkened enclosed room. Poems printed on large pieces of fabric hang in the air. In the distance you can hear Dylan’s voice. If your hearing is acute, you can also hear the Beatles, & recorded voices droning from the many small screens on the walls. One space has Burroughs’ typewriter, other typewriters & tape-recorders. You can hear Julian Beck, of the Living Theatre, talking.

Moving along, you come to a space where there are two fims on small screens about political demonstrations : one against a police raid on a coffee bar in Greenwich Village, the other against the Vietnam War. Bob Dylan, on a large screen, throws away cue cards of the words of Subterranean Homesick Blues, a loop extracted from Don’t Look Back, while behind him in an alley Allen Ginsberg chats with Bob Neuwirth.

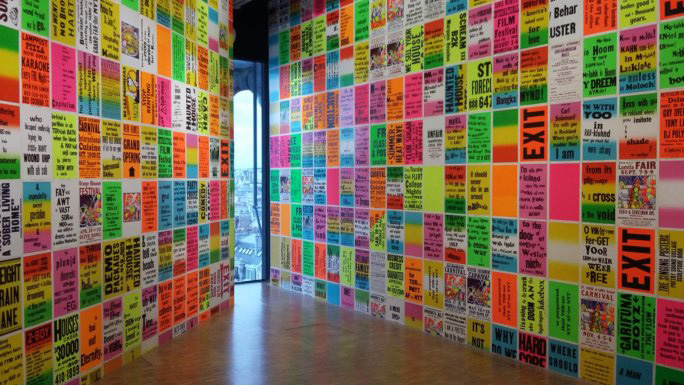

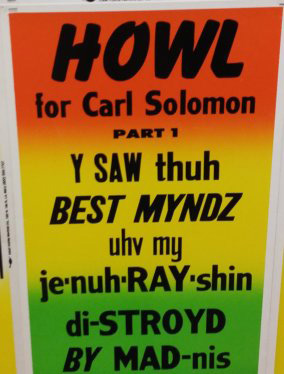

Beyond this, two high walls of Dayglo posters give a phonetic rendering of Howl. Headphones are available so you can listen to Ginsberg reading it. The failed prosecution of Howl for obscenity marked a turning point in the war against censorship in the USA, launched the publisher, Laurence Ferlinghetti, & his publishing house & bookstore City Lights, & simultaneously sealed the Beat Generation’s place in American culture & seared it into our collective memory.

In an adjacent space, visitors are invited to sit & read a small library of books by or about the Beats. A screen is provided where you can, if you have time, watch 4 hours of Ginsberg being interviewed by the founder of Situationism, Jean-Jacques Lebel. The end wall is glass & you can relax looking at the panorama of Paris in the direction of Sacré Coeur. A small screen shows Wholly Communion, the film of the 1965 Albert Hall Poetry Reading where the Beat poets Ginsberg, Corso & Ferlinghetti took pride of place. The reading had a seminal influence on hippies in the UK, & thus of International Times.

Before crossing to the other side of the scroll, you can watch a short extract of Dylan’s film Renaldo & Clara, where Ginsberg & Dylan chat about graves of poets which they have visited.

Spaces each devoted to one of the main places on the Beat circuit form the second half of the exhibition. San Francisco, Big Sur, Venice (California not Italy), Mexico, Tangiers, & Paris itself (or at least the Beat Hotel in Rue Git le Coeur by St Michel in the Latin Quarter) are central to the Beat ethos.

The acoustics mean that you are constantly overwhelmed by sounds coming from several directions from recordings & films. Again there are photos, films & artworks – Burroughs is fimed in William Buys A Parrot, & again in Towers Open Fire, a favourite at the UFO Club in 1967. Crossroads, a terrifying film by Bruce Conner is named after Operation Crossroads which made Bikini Atoll uninhabitable for its 5000 occupants by exploding atomic bombs on their homes. We see the explosion & its aftermath again & again in slow motion – battleships fall on their sides from the force of the blast, & then are engulfed by deadly clouds. The soundtrack is by Terry Riley. Big Sur – The Girls has a Beatles soundtrack, Tomorrow Never Knows. A one hour film called The Flower Thief is playing. There are artworks by Harry Smith, the man who gathered the 6 LP Anthology of folk songs that started the careers of Dylan & Joan Baez. Paul Bowles gathered recordings of Moroccan trance music which plays contunously. A glass case shows works from Semina, a magazine hand produced & sent to just 300 recipients chosen by the publisher. There is a handwritten extract & drawing from Cain’s Book by Alex Trocchi, the compere of the Albert Hall reading.

The show ends with a reconstruction of room 25 in the Beat Hotel, complete with Brion Gysin & Ian Sommerville’s Dream Machine, a primitive stroboscope that was based on an old 50s 78 rpm record player, designed to produce hallucinations.

I think the one word to sum up the exhibition is overload. It is impossible to watch all of the films, and listen to all of the music even if you stay for a whole day – they’re just too long. The sounds and images from different parts of the exhibition overlap.The exhibition is a vast multimedia cutup, which is as it should be.

Chris Holmes

.