Doubly Stolen Fire in his Prosthetic Voice: The Ern Malley Hoax and Fictional Poems in Liverpool

I hadn’t wanted it to be a hoax, but others thought it might still have potential. Mild protests about the distinctions between hoaxes and ‘fictional poems’ were brushed aside in favour of the great event: the hundredth anniversary of the ‘birth’ of Ern Malley.

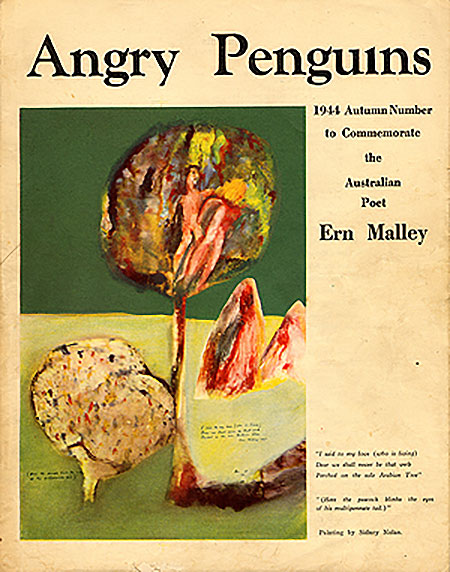

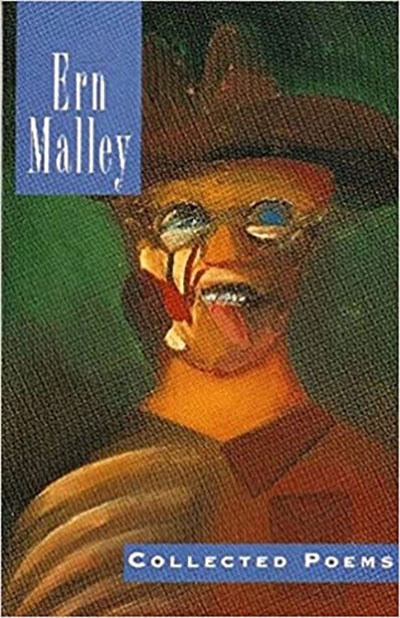

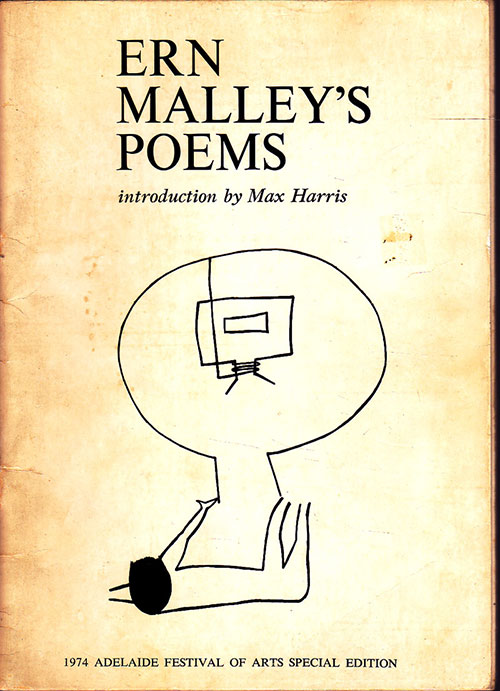

This great Australian literary hoax – the two hoaxers’ prodigious industry at patchwork ersatz modernism; the hoaxed editor’s initial credulity, and then his creeping suspicions; followed by the hoaxers being forced simultaneously to provide more evidence and to cover their tracks; the dramatic prosecution and comic trial of the hoaxed publisher; and the hoaxers’ exposure in the press, and their ambivalent coming clean – is in itself a remarkable story.[1] But added to that the strange afterlife of these events of the mid-1940s – the inability of the hoaxed and his modernistic friends to disbelieve what they had so passionately once believed, that these poems were the work of the great Australian working-class genius poet Malley; and the enduring appeal of the poems themselves to generations of admirers, mainly poets, who have found them far from the incoherent modernist pastiches they were intended to be – makes the story enduring.

I had taught the poems, the legend, and a novel based on the hoax,[2] to a number of cohorts of Masters students, because they raised interesting questions about literary intentionality and value, and the ethics of signature. At the time, I was writing the poems of René Van Valckenborch, published as A Translated Man in 2013, my own experiment in ‘fictional poems’, a fictive author-function which exposes, amongst other things, ‘voice’ as a construct of careful artifice. I would explore with students the difference between that concept and that of a hoax. I could have, but I didn’t, point students to Charles Bernstein’s essay on hoaxes, ‘Fraud’s Phantoms’, in which he quotes my Wayne Pratt spoof of mainstream poetry of the 1980s, and comments: ‘The literary fraud is amusingly announced from the opening pages and the whole work is clearly by Sheppard. Here a mock fraud is used as a literary conceit to send up a range of earnest and sincere poems. Watering the Cactus achieves this aim by being disarmingly straightforward about the terms of the fraud, so that it probably doesn’t qualify as fraud at all, but parody.’ (Bernstein 2011: 208) A disqualification that I was only too pleased to have received. Neither Wayne nor René, or any others, are ‘personae’, it is worth emphasising: they are not masks of the self, donned in order to reveal inner truths, to make the unsaid sayable, the unspeakable spoken; they are essays in otherness, in saying what’s not been said before.[3]

The Australian hoaxers were forced to reveal Ern’s date of birth, 14th March 1918, but given that they had wind that the hoaxed, not as gullible as the story at first suggests, had hired a private detective (he’d turned up at the address from which they’d mailed the poems, a hoaxer’s sisters’), they had to provide a place of birth that would be untraceable in the Australian register offices. Where else than diaspora’s springboard, Liverpool?

I had noticed this anniversary and had thought the figure of Malley should be part of Liverpool legend. After all, much is made of Jung’s dream about Liverpool as the pool of life and he, so far as I know, never visited the city! Of course, I might have celebrated this privately, a select Ern’s Night toast to the dromedary, but little did I know that, miraculously, there was a man living round the corner (less than three minutes’ walk away, up Nicander, and round Stalbridge) who had noticed the anniversary, like me, but who was ready to move on it.

David Whyte had a reason to move on it. Having visited Australia and worked there, he’d become infatuated with the story and its poems (like so many) and had been setting nearly all of the poems as ‘pop songs’, as he cheerfully called them, which he had begun to rehearse and record with musicians in Melbourne – the city where the hoax was planned and executed – and Liverpool. His academic work as Professor of Socio-legal Studies – in part on corruption and industrial fraud – has a peculiar resonance with this project (as well as getting in its way, of course).[4] He found a venue – the new Handyman pub in Smithdown Road, Liverpool – and on the eve of the centenary, performed most of the songs, with his two bands, the two halves of the Ern Malley Orchestra. (This hoax seems to demand pairings.) Patricia Farrell and I read the few remaining poems which had not been set or had not been played on ‘live video-link from Australia’ (actually a DVD, another ruse).

We played the old hoax as a new hoax. The gregarious compere, Kirsteen Paton, leapt into her rôle and narrated Ern’s story straight. He was born in Wavertree, the fair-sized audience was told, a stone’s-throw from the pub. To paraphrase Roy Fisher, Ern Malley’s Old Eggs Still Hatch.

This is not a review of that wonderful event but a reflection upon hoaxing and fictionalising poems. [5] My diary records this contextual chaos: many of the players had been on a university picket line trying to save their pensions all day. I remember telling the audience something about the influence of George Barker, a poet of the 1930s I had once met, on Malley, which must have made him seem more real. We were genuinely exuberant about the man and his work but the performances were tinged with understated, but theatrical, melancholy. I thought most people would either know the story or would intuit our frequent irony. Like the poems themselves, the performance was peppered with hints about Malley’s non-existence. (This is a daring feature of many hoaxes; like serial killers the perps want to be caught.) Perhaps a year of post-truth Trump and fraudulent Brexiteering had blunted critical functions. I know of two audience members who were seduced by the memorialising we had set up. One, a professor, emailed his literary critic friend the next day to comment on his discovery of this untutored genius: he was firmly put to rights with a laugh.

Charles Bernstein’s essay tells us (with the Malley poems partly in mind): ‘What is written out of a desire to expose the limits of a particular style (or rhetoric) may ultimately become exemplary of unrealized potential in the style; ironizing of the style may create a thickening of the artifice and with it an intensification of the aesthetic experience.’ (Bernstein 2011: 224) This is an astute and accurate description of why many have liked the poems. I have been singing and recording some of David Whyte’s songs and Bernstein’s conjecture, I think, partly explains my pleasure in the Malley lyrics, though I think there is a further stage beyond Bernstein’s intensity, one at which irony is replaced by our earnest inhabiting of the words, when the artifice and form become embedded and embodied, as it were. Beyond encounter.

This still leaves what Bernstein calls the originating ‘poetics of ressentiment’ of the hoaxers to be dealt with. (Bernstein 2011: 206) ‘Literary fraud is an ethically troubling activity not because it undermines the rhetoric of sincerity … but because it violates the good-faith relationship of parties making a cultural exchange…’ (Bernstein 2011: 210) This might be said of our own hoaxing echo of a hoax, although we had, as it were, no hoax to grind. One of the effects of the processes by which we come to love Ern Malley’s poems is that we overlook, but perhaps we also override, the fact that ‘these frauds’ – again Bernstein has the Malley Hoax partly in his sights – ‘were used as a way of shoring up moral discourse against the perceived relativism of contemporary culture.’ (Bernstein 2011: 210) In this case, the meaningless collagist referentiality of ‘modernism’ and its attendant freedoms. ‘These authors,’ we are reminded, ‘embraced fraud not in a joyous or comic dance with the improbabilities or insufficiencies of authenticity, but rather out of a sense of moral outrage – specifically of white male rage’ (Bernstein: 211). [6] We must avoid this in our embrace of the poems themselves. It seems to me every joyous or comic re-enactment of them – in recitation, in song – subverts the resentment and rage into the artificial and aesthetic, in their most active and positive form, and partly as I’ve described it above, and elsewhere.[7]

This is why, even as early as the Wayne Pratt spoofs, and as recently as the co-created works of the European Union of Imaginary Authors (EUOIA)[8], collected in Twitters for a Lark in 2017, and specifically in the (fictional) introduction to A Translated Man, I prefer to openly acknowledge the fictional nature of my projects; I adopt a definition of the ‘fictional poem’ (and thereby the ‘fictional poets’ that I have filled the charabanc of my poetic outings with) from a suggestive (but relatively autonomous) remark of Gerald Bruns. He was thinking of poems as they appear in novels, but the point holds.

A fictional poem would be a poem held in place less by literary history than by one of the categories that the logical world keeps in supply: conceptual models, possible worlds, speculative systems, hypothetical constructions in all their infinite variation. (Bruns 2005:105-6)

To conclude the Ern Malley evening, I read one of my fictional poems from Twitters for a Lark, a book with a clear conceptual model. It is one of the few poems not co-created, but written by myself alone, although in the context of the book, which presents a fictional poet for each of the EU countries, I, Robert Sheppard, wrote the fictional poem of the fictional UK poet, ‘Robert Sheppard’. Fortunately (for them) I spared the audience knowledge of this complexity, but I could have pointed to ‘Sheppard’’s fictional biography at the back of the book (written by Patricia Farrell). The poem was ‘Robert Sheppard’’s ‘The Ern Malley Suite’, a sequence based upon the Max Ernst-like collages that one of the Malley hoaxers made, but which remained in reserve, and is seldom discussed. The Ern Malley that we see briefly in the poem is certainly in accord with my way of perceiving his tricksterish majesty as it surpasses his resentful origins in pure hoax:

erect a statue in heaven as though

god needs another effigy

a Prometheus to lay eggs on his own plinth

as mere man back-flips above

the pools of England

to land on his feet like a real man

with doubly stolen fire in his prosthetic voice (Sheppard 2017: 97)

‘If the right poets for the times don’t exist, then they have to be invented,’ goes the axiom of the EUOIA (more truthfully, the blurb of Twitters for a Lark). This invention need not lead to hoaxing, just as the lies of Trump need not lead to a Wall, the dissembling of the Referendum need not lead to the worst free market little Englandism of a Hard Brexit. Possible worlds, not impossible ones. And with such people in them, writing their poems! Like Borges, in his fable ‘Borges and I’, I could say that I do not know which ‘Robert Sheppard’ has written this piece, but I do.[9] And you do too, don’t you?

Works Cited

Bernstein, Charles. Attack of the Difficult Poem. Chicago and London, The University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Brooks, David. The Sons of Clovis: Ern Malley, Adoré Floupette and a Secret History of Australian Poetry. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 2011.

Borges, Jorge Luis. Labyrinths. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

Bruns, Gerald L. The Material of Poetry. Athens and London: The University of Georgia Press, 2005.

Peter Carey. My Life as a Fake. London and Boston: Faber and Faber, 2003.

Heywood, Michael. The Ern Malley Affair. London and Boston: Faber and Faber, 1993.

Sheppard, Robert. Watering the Cactus. Wayne Pratt: Watering the Cactus – the deathbed edition, 1999 Ship of Fools, London, 1992, revised 1999

Sheppard, Robert. The Meaning of Form in Contemporary Innovative Poetry, New York: Palgrave, 2016.

Sheppard, Robert. A Translated Man, Exeter: Shearsman Books, 2013.

Sheppard, Robert. Twitters for a Lark: Poetry of the European Union of Imaginary Authors (with Others), Bristol: Shearsman Books, 2017.

Sheppard, Robert. Complete Twentieth Century Blues, Cambridge: Salt Publishing, 2008.

Whyte, David. Ecocide: Kill the Corporation Before it Kills us. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020.

[1] It is told in great detail, and with aplomb, in Michael Heywood’s The Ern Malley Affair. London and Boston: Faber and Faber, 1993. It is contextualised further in David Brooks’ The Sons of Clovis: Ern Malley, Adoré Floupette and a Secret History of Australian Poetry. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press, 2011.

[2] Peter Carey’s My Life as a Fake. London and Boston: Faber and Faber, 2003.

[3] The Wayne Pratt poems of Watering the Cactus, Ship of Fools, 1993, are reprinted in Complete Twentieth Century Blues. Cambridge: Salt Publishing, 2008.

[4] As editor of the book How Corrupt is Britain? London: Pluto Press, 2015. I particularly recommend his Ecocide: Kill the Corporation Before it Kills Us. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020, which argues that true ecological justice is incompatible with world capitalism and its ubiquitous trans-national corporations, unless challenged and constrained by robust international law.

[5] See my blogpost for an account of the evening: ‘Ern Malley 1918-1943’: https://robertsheppard.blogspot.com/2018/03/ern-malley-1918-1943-celebrating_14.html (accessed 24th January 2019).

[6] Bernstein is also responding to the Alan Sokal and Kent Johnson’s ‘Araki Yasusada’ hoaxes, which are more egregious than the Malley Hoax, which still had an element of ‘jape’ about it. I also think class is more at play than race in the Malley Hoax, though in a complex way.

[7] See the introduction to my The Meaning of Form in Contemporary Innovative Poetry, New York: Palgrave, 2016, for my argument about form.

[8] See also the EUOIA website at www.euoia.weebly.com.

[9] ‘Borges and I’, in Borges, Jorge Luis. Labyrinths. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970: 282-3.

Robert Sheppard