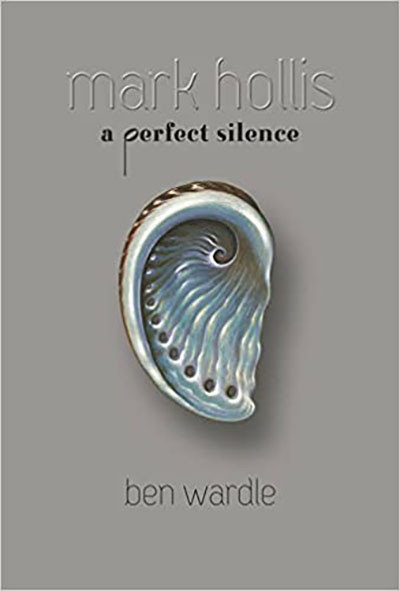

Mark Hollis. A Perfect Silence, Ben Wardle (Rocket 88)

In only five studio albums the band Talk Talk went from synthesizer pop to experimental rock. To start with they were – quite rightly I feel – compared to the likes of Duran Duran (who they supported on tour) and written off by the music press, but by their third album, The Colour of Spring, something was up. The shallow veneer of pop was starting to peel, and by the band’s final two albums, Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock, no trace remained. It is these two albums which have become cult classics, two albums of carefully constructed strange music with awkward textures, rhythms, noisy asides and dense mumbled vocals hidden in the mix.

Truth be told, I think a lot of criticism has been written after the fact, hindsight allowing some to pick up on the few interesting elements of the first two albums, and making far more of The Colour of Spring than it deserves. In retrospect it’s okay, but not great, and that’s mostly because it isn’t either of their first two pop albums. Instead, it’s a brief collection of eight songs that start to offer some shade and space rather than beat you over the head with overproduced hooks.

Like a lot of albums assembled in the studio, part of me always wonders about the process. Does the odd cough, squeak or cymbal sound actually make that much difference? Does the music really offer up any sense of the room’s ambience or mood? Wouldn’t it have been easier to just record the bloody thing with a band? I think back to Steely Dan albums which were also made with the use of numerous session players, endless studio time, and some sense of struggle towards a perfection that only Becker & Fagen could hear in their heads. Jump forward a few years and look at Steely Dan enjoying themselves out on the road, and you wonder what it was all about: it’s the songs that matter and have survived reinvention as jazz big band numbers or rock wigouts.

Of course, Mark Hollis’ songs on the final two Talk Talk albums are nothing like Steely Dan’s, in fact ‘song’ doesn’t seem an apt term here. They are perhaps more akin to works by Can or David Sylvian, studio constructions assembled from endless improvisations and versions. They were never played live and weren’t meant to be: the band Talk Talk hardly existed by the time these albums were recorded, it was only Mark Hollis and the rhythm section left, along with producer and co-composer Tim Friese-Greene. Many of the tracks were built up over drum/rhythm patterns, with an endless parade of guests, friends and session musicians invited to the studio, with most of their work subsequently binned or reduced to one or two bars, the odd solo, noise or breath, often placed somewhere else on the album, far away from where they were first played.

Although Hollis had a sociable past and was able for several years to perform as a pop frontman, with mirror shades, long hair, beads and unbuttoned shirt, as time went on he became more and more private, desiring time with his family and refusing to facilitate the record companies’ publicity efforts which were meant to accompany each album or single release. He particularly found the stab-in-the-back nature of the UK music press unbearable, especially in contrast to informed critics in mainland Europe, who he could hold intelligent conversations with and who didn’t look bored when he mentioned jazz or avant-garde classical composers as he was wont to do.

After Laughing Stock, there was one solo Mark Hollis album and then nothing. Hollis found the solitude he wanted, time to himself, for family and friends, and total disengaged from the music biz, although at first there were some discussions about film soundtracks. Hollis died of cancer early in 2019, causing a spate of Talk Talk retrospective articles, often in the guise of obituaries, and now we have the first in-depth biography from author and university lecturer Ben Wardle.

Biographies are funny things. We all want to know what motivates and shapes people, their ideas, ambitions and dreams, but in the end we are only left with the books, speeches or music they made. Labels on art works don’t change the physical painting above it, just offer one way of understanding it, just as blurbs and quotes on the back of books frame them in a certain way for the reader. Comparing, say, Len Deighton to James Joyce, doesn’t actually make Deighton’s book experimental modernism; artspeak about deflated balloons on a gallery wall doesn’t change my lack of interest in the intellectual shallowness and visual paucity of the work.

So, do I need to know about Mark Hollis’ elder brother, who facilitated access to not only his record collection but the live world of bands like Eddie & the Hot Rods? Or that he became a junkie? Does it help my listening to know that some of the music was recorded in a studio where everyone assumed roles based on Pete ‘n’ Dud’s offensive characters Derek & Clive, or that Hollis could be a bit of a bully to his bandmates? Does the ‘true story’ of record company shenanigans, manipulated contracts and their lack of support change what I think? Or that Hollis basically took the majority of album and song royalties, and also walked away with a huge amount of advance money from Polydor? Not really.

It is, however, an intriguing story, although I suspect it’s one of many possible versions. Wardle has done thorough research and much interviewing, but it’s clear several close associates of Hollis didn’t want to talk to him (or anyone else) about the past. Even some of those who enjoyed the recording and mixing process and believe in the final music didn’t want to go back in time. And I like the fact that it’s made clear that Hollis could be arrogant, egotistical, unpleasant and self-opinionated as much as a good bloke, visionary artist and musical genius.

Mark Hollis. A Perfect Silence is an aside, really. It is for people like me who enjoy trying to understand the creative process and what drives certain individuals; for those who are interested in the politics, finances and processes of the music business, and intrigued by those who engage with it and seem to come out on top. In the end Hollis didn’t care about anything other than the music and his family, and he would trample on people, manipulate friends and colleagues, or simply clam up and walk away, when he thought it best.

Wardle hasn’t allowed Hollis to entirely disappear or remain silent. His engaging and fluid book – despite several typos and the fact that he thinks the A4 flyover at Hammersmith is the Westway – offers a thorough biographical picture of a complex and difficult person who fought to make the music he wanted to hear. It challenges some of the stereotypical myths that have been created around Hollis since his death, whilst confirming much rumour and gossip as true. It also stands as a sociological study of both the ‘tortured artist’ and the music business back in the 1980s before it had to reinvent itself and fight for its life against the digital dissemination of and access to music around the world.

Mark Hollis was no saint, and Wardle does not try to canonise him; neither does he pretend to be a musicologist or critical theorist, attempting to explain the albums to the reader. He collates, sieves and orders information, juxtaposing and contrasting it for the reader, offering fact and opinion, insight and empathy, about his subject. Although much of this book perhaps contradicts Hollis’ opinion that ‘”only people who know who they are and who can deal with silence can create really new art”‘ or the fact that he’d rather not talk about his own work, Mark Hollis. A Perfect Silence is a persuasive, quiet and authoritative book. It may disturb the silence Hollis craved, but it also informs and facilitates the music for the reader and listener.

Rupert Loydell