The Secret

Low Moor Wood goes back a long way, perhaps even to the time of the great forests that once covered much of Britain. The oldest trees there have been around for hundreds of years. There are a few hazel coppice stools, mainly at the southern end, and there’s a path, much used by dog-walkers, that cuts across one corner but, otherwise, there are few obvious signs that people have ever interfered with the place in recent times. The dead rot where they fall. If you leave the path and go looking, though, you’ll find, under the nettles and the moss, lines of stones, criss-crossing the whole area of the wood.

It was Peter Williams, a local historian and avid detectorist, who first made something of them. Having discovered a number of unusual metallic objects in the wood, he became curious about the stones. He went on to map them, along with the location of various mounds and depressions in the ground. He discovered that they are almost certainly the remains of the walls of buildings or enclosures in what appears to have been a farmstead or settlement that may even have predated the wood itself.

I wasn’t lucky enough to know Williams, as I moved to the village a year or so after his death. I did, however, get to know his long-time companion and house-mate, the artist Jean Hardacre. She was well into her seventies by then. She allowed me access to his notebooks, his diaries and the private museum he’d created (and which she still maintained) on the first floor of the stone-built cottage she’d shared with him during the last three decades of his life. It was – and still is – an impressive collection. I asked her why he’d not shared his findings with the world. In reply, she painted a picture of a kindly though misanthropic man who hated bureaucracy and the idea of all the paper-work which declaring his finds would’ve entailed. One unfortunate result of his reticence was that he’d been unable to put anything like an accurate date to his discoveries.

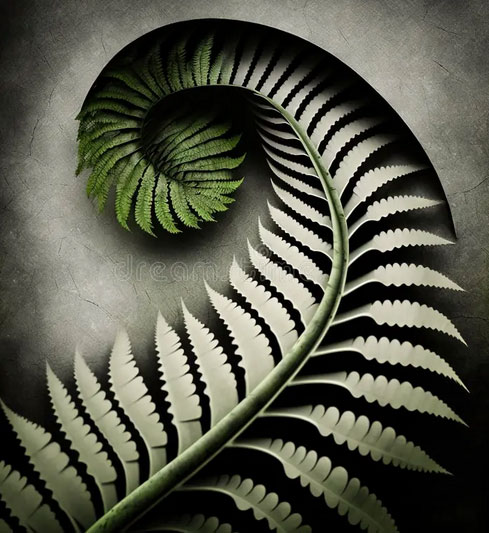

The objects on display in the museum resemble nothing I’ve ever seen. Having examined them myself and read what Williams had to say about them in his notebooks, I can see no link between them and any culture known to have inhabited Britain at any time. He himself had measured the angles of the corners on the more sophisticated metal artefacts and concluded that their construction would’ve required a knowledge of fractals and the Mandelbrot set. Acting on an intuition, he went back to the maps he’d made of the settlement and found the same mathematics at work. The settlement in the wood, he concluded, was perhaps part of a structure that could’ve extended outwards indefinitely.

Destiny

It becomes clear from reading his diary that, as time went on, Williams became less interested in the scientific aspects of his work and more interested in the esoteric. He writes down his dreams and speculates as to the origin of local legends and customs. There are drawings of people in his notebooks, people he’s seen in his dreams, dressed in unusual clothes: short, brightly-coloured tunics, gaiters, knee-length frock-coats that look as if they might’ve come out of the eighteenth century. He makes himself similar clothes, although he still keeps his discoveries secret, offering no public explanation for his behaviour. Local people are not particularly surprised, as they already consider him to be an eccentric. He stops using the metal detector and develops an interest in dowsing. By the time of his death he has become convinced that he’d come to live in the village for reasons beyond his control.

The Machine

Jean was kind enough to give me Williams’ old metal detector. I think she was pleased I’d taken an interest in his work and thought that perhaps I might take it up where he’d left off when he first became ill. It’s a Sabretron 2000, a state-of-the art machine in its day but quite outdated now. Williams had stored it in the original cardboard box, along with the manual that came with it. Well-used, its blue, plastic casing is scratched and faded. I’ve never used it myself, but I have occasionally leafed through the well-thumbed manual. It explains how the machine’s broad-band spectrum circuitry broadcasts on seventeen frequencies simultaneously, allowing it to function in a wide range of environments. It’s leaning in the corner, here, as I write.

The Artist

In this account, at Jean’s request, all the names of both people and places have been changed. Jean is a professional artist who paints acrylics and makes and sells her own jewellery. Those who appreciate her work know nothing of the civilisation which inspires much of it. She paints in a naïve style and is known for her large, densely-packed canvasses depicting communities of brightly-coloured houses arranged in streets laid out in fractal-like patterns. The pendants and ear-rings she makes are also clearly influenced by Williams’ discoveries.

The Beast

“Today I went off on my usual walk across the fields, hoping to see it again – whatever it is, I’m not sure we’ll ever know for sure. The signs were good. After all the rain we had yesterday, certain sections of the lane had become flooded. My progress through the grey, still floodwater (which almost reached the top of my wellington boots) disturbed the surface, breaking up the reflections of the bare branches of the ash trees. This time last year, in similar conditions, I thought I’d glimpsed it, still in its winter coat, flitting across a gap in the hedgerow on the far side of the first field. I’d heard talk of it, but I’d never seen it before. I must’ve mentioned what I’d seen to old Turner, the man next door, because, not long after, everyone was talking about it. It even got a mention in the village free-sheet, in a column squeezed between an advert for yoga classes and another for a chimney-sweep. When I realised what I’d started, I wished I’d kept shtum. After all, it was no more than corner-of-the-eye stuff.

“Ever since, whenever I set off on a walk, I can’t help but wonder if I’ll encounter it. I can’t say I have, but I have had strange experiences which I can’t help but associate with it. Often, as I’m walking, I find my thoughts interrupted for no obvious reason and a shiver passes through me. I invariably stop and look around, hoping to catch sight of it, but I’ve not, as yet, seen any sign. Whenever this happens, I ask myself if perhaps it crossed the path I’m on not long before. And only last week, I came across a gap in the hedge patched with old pieces of wood, held together with rusty nails. I felt disorientated: the past, the present and the future seemed all entangled there. I was aware of a strong, musky smell. Perhaps it had been there recently? I don’t know how long I stood there: I had to tear myself away. My memory of the episode is like a memory of delirium, like a film shot in black and white on Super-8.” From the notebooks of Peter Williams, dated March, 2012.

Extrapolation

I have tried to carry on where Williams left off with the more scientific aspects of his work. I began by making a careful study of the ground-plans he drew in his notebooks. I visited the woods to see if I could reproduce his findings. I had, at the back of my mind, the possibility that his delusions might have begun long before he rejected the more rigorous, scientific approach he’d applied to his earlier observations. As it was, I found everything exactly as he described it. This came as a relief. I next tried to extrapolate from the plans, using the same mathematics, to create possible lay-outs of any now-vanished extended settlement, something Williams never got round to doing. I also began going for extended walks in the area around the wood, partly for the pleasure of it, but also to see if I could find evidence of such a structure. You can imagine my elation when, half a mile away and close to the hill-top at Scarcote Brow, I discovered a line of stone-work almost identical to those found in the wood. It’s easy to miss, as it’s almost entirely hidden beneath bracken. I took measurements and discovered that it was within two feet of where one of my projections expected it to be. It’s alignment was off by less than half a degree. I have since discovered the remains of other short sections of wall at several other sites.

.

Dominic Rivron

.

.

This leaves me wanting the writer to keep going with his observations. Has he begun to move further along the ‘discovery trail’? What will he find at the end of it? Will he see the ‘beast’ again and what is it? I suspect these questions took over Williams’s life as he aged. Will they take over the writer’s life more and more? Is there more to discover or is the whole thing a figment of the imaginsation blown up out of all preportion?

Comment by Pat Thistlethwaite on 5 May, 2024 at 8:22 am