John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson

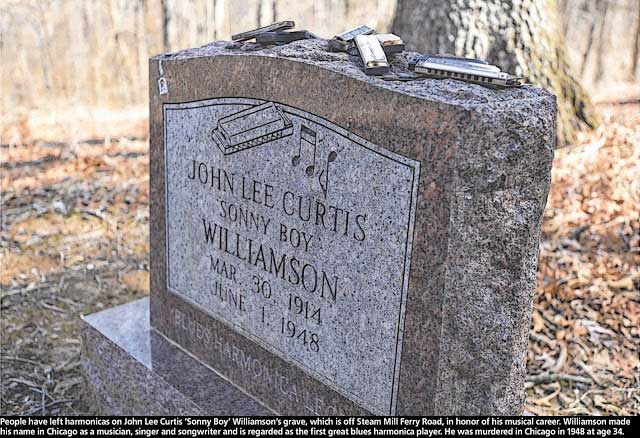

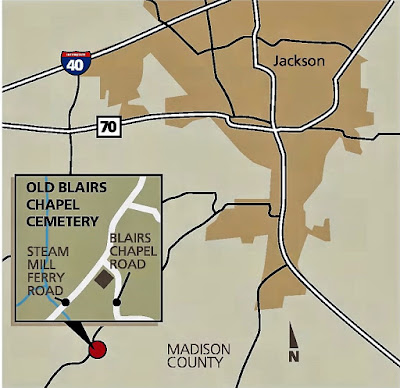

On a hilltop, under an oak in southwest Madison County, a tombstone is adorned with harmonicas and coins left by visitors. Aside from songbirds and gusts of wind that rustle the leaves, it is a quiet place, far removed from the boisterous nightclubs of south Chicago in the 1940s. John Lee Curtis “Sonny Boy” Williamson is buried beneath that stone, but his legend lives on in the world of blues music. He made his name in Chicago as a musician, singer and songwriter and is regarded as the first great blues harmonica player. Sonny Boy was born 100 years ago today near his grave. Artists still record his songs and at-tempt to duplicate his magic with a harmonica.

He was 34 and enjoying another nationwide hit with his recording of “Shake the Boogie” when he was murdered in Chicago in 1948.His wife, Lacey Belle Davidson, brought him home, granting the request he made known in a verse of one of his songs: “I want my body buried in Jackson, Tennessee.”

Mentor Mourned

William “Billy Boy” Arnold was 12 when Sonny Boy died. Hearing the news was the most shocking moment of his young life.

“I rang the doorbell of his apartment house on Giles Street here in Chicago,” Arnold said. “He lived on the second floor. A lady stuck her head out of a window and asked who I was looking for. I said, ‘Sonny Boy.’ She said, `Oh, baby, ain’t you heard? He got killed.'”

“I was so sad,” Arnold said. “Sonny Boy was my buddy. He was going to show me how to play the harmonica like he did.”

Arnold had heard Sonny Boy’s records and was in love with the music. He got a harmonica and tried to play like his idol. When he discovered that Sonny Boy lived nearby, he recruited a cousin and friend to go with him to try to meet Sonny Boy. They rang the doorbell, and Sonny Boy answered.

“We had never seen him, and we said, `We want to see Sonny Boy.’ He said, ‘I’m him. Come on up.'”

He led the boys to his apartment, introduced them to some house guests and asked how he could help them. Arnold asked Sonny Boy, “How do you make the harmonica go, ‘Wow, wow, wow?'”

Sonny Boy laughed and said, “You have to choke it.” Then he showed Arnold how to “bend the notes,” and Arnold went home and practiced. A few days later he returned. Sonny Boy hooked up his amp and mike and let me play along with the record ‘Sugar Gal.’ That was one of his hits,” Arnold said. “He laughed and seemed to get a kick out of me wanting to play like him. He told his guests, ‘He’s going to be better than me.’

“He was real nice to me, and I couldn’t believe it when I went back to his house the third time and they told me he was killed. He was the first to make the harp a lead instrument in blues mu-sic. He could sing and play that harp without missing a beat. All the guys who came after him didn’t have the talent he had.” Arnold cherished the brief time he spent with his mentor and kept working on his skills. He became “Billy Boy” Arnold and a famous Chicago blues harmonica performer in his own right. He is 78 and still plays today, most recently in Spain.

Familiar Start

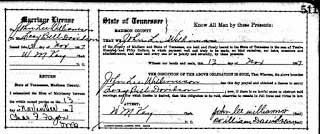

| John Lee and Lacey Belle’s marriage license |

Sonny Boy probably saw himself in Arnold because Sonny Boy began his love affair with the harmonica when he was 11. His mother, Nancy Utley, gave him his first harmonica for Christmas. He taught himself how to play, and friends said he quickly learned how to make the instrument squall and sound like a pack of hounds.

His father, Rafe Williamson, died when he was a baby. His stepfather, Willie Utley, died during World War II. The family attended Blairs Chapel CME Church, which was founded in 1881 about a mile off Steam Mill Ferry Road. It relocated to its present location on Steam Mill Ferry in 1971. Sonny Boy began his musical career singing at church in a quartet named The Four Lamb Jubilee. But his harmonica was not allowed at church.

Word spread about his talent, and he began performing as a teenager at regional shows with bluesmen such as Sleepy John Estes and Yank Rachell. That led to Memphis, St. Louis and Chicago. He married Lacey Belle in Madison County on Nov. 13, 1937, and they soon moved to Chicago where Sonny Boy recorded for RCA’s Bluebird label.

Making it Big

His first recording session produced classics such as “Good Morning Little School Girl,” “Sugar Mama Blues” and “Bluebird Blues.” From 1937 to 1947, he recorded more than 120 songs for RCA. “Good Morning Little School Girl” is among the most recorded blues songs in history. One of the verses says:

“Now, you be my baby, mm, come on an’ be my baby, mm. I’ll buy you a diamond, I’ll buy you a diamond ring. Well, if you don’t be my little woman, then I won’t buy you a doggone thing.”

Sonny Boy’s material has been recorded by dozens of musicians, including Rod Stewart, Van Morrison, The Yardbirds, The Grateful Dead, John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters. He often wrote and sang about home, such as in “Shannon Street Blues,” in which he refers to the street in downtown Jackson and to his wife, Lacey.

“I went down on Shannon Street, now to buy some alcohol,” he moaned. “Lacey tells me, papa, papa, well you ain’t no good at all…You don’t make me happy, so long as you fool with this alcohol.'”

In typical blues tradition, Sonny Boy wrote about women, booze and empty pockets, bill collectors, welfare and even his old refrigerator in “Frigidaire Blues.” He was the first to cup both the microphone and harmonica in his hands to achieve a unique amplification and sound. It was said that he put pillows under his feet during recording sessions to muffle the sound of his shoes as they tapped to the beat.

Blues historians unanimously say that Sonny Boy was the most influential harmonica player of his generation. He was inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame in 1980.

“He influenced almost every blues harmonica player who came after him,” said David Evans, a University of Memphis professor who is a noted specialist in American folk and popular music. “He pioneered in treating the harmonica as a second voice, answering and interacting with the vocal. Previously, most harmonica players simply played interlude choruses or harmonica solo numbers…He was highly respected and had many imitators of both his harmonica and vocal style.”

Sonny Boy was at the top of his profession and would have built upon his reputation if he had lived. David Evans thinks “he would have been a major figure in the Chicago blues scene of the 1950s and 1960s,” who probably would have toured internationally and collaborated with blues-rock stars of the 1960s. The amazing talent, no doubt, would have also composed more tunes that would come to be regarded as standards of the genre.

But the brutal end came suddenly for Sonny Boy.

Dead at 34

On June 1, 1948, Sonny Boy Williamson died from a vicious beating after a performance at the Plantation Club near his home. The official police report indicates he was robbed and beaten as he walked home.

“Billy Boy” Arnold, however, claims to know the real story. He claimed that the assault “rumor…got started to cover up what really happened,” and a booking agent told him a tale that he got from a “musician who saw what happened.” After his engagement at the Plantation Club, Sonny Boy went over to a private residence for its after-hours whiskey and games of chance. He won a great deal of money from several unfortunate, dangerous gamblers. “The musician said that the guy running the joint went and got three or four guys and jumped on Sonny Boy to get the money back,” according to Arnold. The owner of the home And I guess nobody wanted to get involved. They took him to his house and left him at the door.”

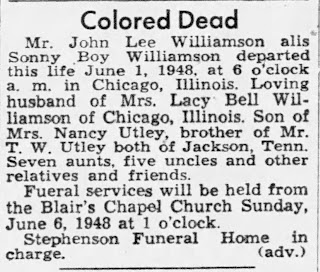

| The Jackson Sun, June 6, 1948. |

“Sonny Boy’s wife told me that when she found him leaning against the door, he told her he had won more money that night than he ever had in his life,” Arnold said. “But there was no money on him. She helped him up the stairs to their apartment, but he passed out.”

An ambulance was called, and he was taken to a hospital, where he died at 6 a.m.

His death notice appeared in The Jackson Sun on Sunday, June 6, 1948. It was buried on page 15 among the classified ads under the heading “Colored Dead.” Three short paragraphs said nothing about his musical career.

Late Recognition

For 42 years, Sonny Boy’s remains rested unnoticed on top of the hill at the old Blairs Chapel Cemetery. The site was unmarked except for a small, metal rectangle that funeral homes place at graves for a temporary indicator. Kudzu blanketed the hill, and few challenged the fallen trees and thick brush to visit the area’s graves.

That changed in 1990 when Michael Baker, Judy Pennel and Jack Wood of the Jackson-Madison County Library got involved. Realizing the significance of Sonny Boy’s contributions to the nation’s blues music, they researched his life, wrote articles and gained local and national support.

That led to the placement of a red granite headstone at Sonny Boy’s grave and a Tennessee State Historical Marker at the intersection of Tenn. 18 and Caldwell Road near Malesus Park in Jackson.

On June 1, 1990, the 42nd anniversary of his death, the city held a Sonny Boy Williamson Day to celebrate his life and dedicate the new markers. A blues festival evolved on Shannon Street that saluted Sonny Boy and lasted about 20 years.

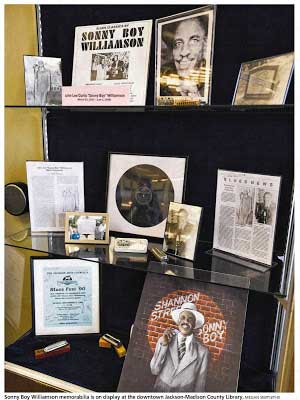

This week the downtown library location has a display of Sonny Boy memorabilia in recognition of his 100th birthday. And Sonny Boy’s music is plentiful on the Internet. You can Google his name and find him singing many of his songs on YouTube.

But be certain to use the name Sonny Boy Williamson I to distinguish between him and Sonny Boy Williamson II. Alex Miller from Mississippi, another blues harmonica player, took the name Sonny Boy Williamson and used it professionally after the first Sonny Boy’s death.

Baker, who often visits Sonny Boy’s grave, said he is glad the library pushed to recognize the blues musician.

“It was a great project to do and one of the things I’m most proud of in my career,” Baker said. “It’s gratifying even today when school kids come in to do research on Sonny Boy for term papers.

“He was a phenomenal musician, singer and writer, so he had it all and was at the top of his game when he died. The man did a lot in 34 years.”

By Dan Morris