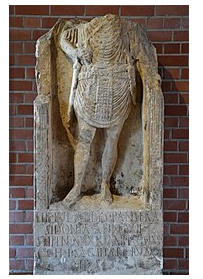

The tombstone of Tiberius Julius Abdes Pantera, discovered in Bingerbruck, Germany, 1859. The inscription reads:

Tiberius Julius Abdes Pantera

from Sidon, aged 62 years

served 40 years, former standard bearer

of the first cohort of archers

lies here

The words of Tiberius Julius Abdes Pantera

I’m tired now. An old man, sixty-two years of age, and a servant of the Empire for forty of those years. A proud member of the First Cohort of Archers, and as upright a Standard Bearer as you could find. A conquering Roman, despite my Phoenician-Caananite blood.

I was born and bred in Sidon, a city-state dependent for trade on its fishing industry. Annexed by Rome forty-two years before my birth, and more Greek than Arab, it was a cosmopolitan place to live. As a boy, I played along the sea front and the harbour walls, zigzagging in and out of the baskets of fish, the boats and the bustle with my friends, shouting at strange-looking foreigners, and hunting small game with my bow and arrows in the orchards and woods of the surrounding area; something which stood me in good stead for my future in the Military. Not for me the casting of nets. I wanted out.

At the age of seventeen, I joined up. It wasn’t easy to begin with. The training, the discipline, the casual brutality of it all. But I stuck it out, and I was a valued comrade, an indispensible part of the team. After less than a year, I was moved from Sidon to Antioch, under the charge of the Syrian Governor, Publius Quinctilius Varus. He was a tough bastard, and a harsh taskmaster, who brooked no dissent – not that anyone was ever likely to challenge his authority, since he had the ear of Augustus Caesar himself.

About that time, in neighbouring Palestine-Judea, the King died. A madman, if ever there was one, he was even crazier than his fellow countrymen. Herod the Great, so-called, had ruled with a vicious disregard and contempt for his own people and their peculiarly miserable singular god, placing personal wealth and pleasure above all else. Truth to tell, there was much rejoicing across the land when he passed. Unfortunately, there was something else, too. Rebellion. And rebellion spelled trouble for us.

Within days of Herod’s death, there were bloody uprisings everywhere, with three in particular requiring our attention. The new King of the Jews, Archelaus, was only a year older than me, and, naturally, he turned to Rome at the earliest opportunity. Judas, the son of a bandit executed by Herod, attacked the city of Sephoris in Galilee. In Jericho, a certain Simon burnt down the royal palaces, and a shepherd named Athronges declared Emmaus to be his new state capital. It was up to us to sort out the mess, which is exactly what we did.

With a fighting force of two legions, plus allied and auxiliary forces, including King Aretas of Arabia Petrea, we set off from Antioch, with Varus at the helm.

Simon was put in his place damned quick, while Emmaus was burnt to the ground. I was part of the force which attacked Sephoris, and it wasn’t long before the city was razed, and its rebellious occupants captured, to be sold as slaves. Job done, as far as I was concerned. It still makes me shiver when I think about my very first battle, and the disciplined way I killed fellow human beings. While Varus continued marching towards Jerusalem, I stayed behind near the ruined city, and patrolled the general area of Ptolemais, along with a small contingent of both Roman and local troops. It wasn’t difficult work, since the local inhabitants lived, for the most part, in smallish clusters of ten to fifteen houses or so, with most of the men scratching out an existence in the fields, tending their flocks of sheep, and the women going about the daily business of washing clothes and cooking in the open air every day, in front of their respective one-roomed houses. Back in Sidon, we’d have called them hovels, but they seemed to pass as standard in Galilee.

On one very particular day, a day that’s burned in me all this time, I found myself in a dirt-poor hamlet of six or seven houses; a place so insignificant it had no name. It was baking hot, so all of the local women were doing their usual chores in the shadows of the buildings. Dressed in white robes, with their faces half-covered, I guessed they comprised one entire extended family, although I might have been wrong. It was the usual thing in these parts for just about everyone to be related to everyone else. ‘Close-knit’ doesn’t begin to describe it. As I strolled past one figure, who was rinsing a richly-coloured cloth, she stared up at me, and my world stopped. She had the blackest eyes I’d ever seen, and it seemed as if she cut straight through me, and into my young heart. I must have held my breath, since, when I audibly exhaled, I sensed she half-smiled, although her mouth was hidden. Despite orders not to speak to the locals, let alone fraternise, unless absolutely necessary, I muttered a greeting of sorts, and she responded by slightly inclining her head towards me. I was lost.

Back at camp, I made a few discreet inquiries about the place I’d been to, and about the people who lived there. There wasn’t much to tell. A family settlement of about seventy to eighty, and all of them squeezed into seven houses, plus a special building in which they worshiped their mirthless god. Other than that, nothing. I knew, there and then, I had to return, and find out more about the girl with the black eyes and the hidden smile. Something compelled me.

A couple of days later, I willingly volunteered to patrol the same area, in the hope of seeing her again. Another scorching day, with the women sheltering from the sun’s rays, and the men in the fields. When I drew close to the spot where she’d been rinsing the cloth, it was an older woman who sat in her place. Knowing that as a Roman, I’d be treated with a certain respect, grudging or otherwise, I dared to ask her about the young girl – something along the lines of “it’s possible she might have useful information”, or some such rubbish. The older woman sized me up through screwed tight lids, snorted, and replied, in a mix of Arabic and Hebrew, “she’s in the fields, with food for her brothers”, gesturing behind her as she spoke. I nodded, as if it was the most casual of matters, and set off to find her.

After a traipse of about a leuga, through dusty scrub and stony earth, I saw the girl – ‘my’ girl, as I’d begun to think of her – walking towards me. She saw me, too, and it seemed as if her entire shape reached out to me, although that might just have been my excited imagination over-stretching itself. As she came closer, she let slip the flap of robe which concealed her mouth, and there it was, that half-smile on her lips I’d sensed two days earlier. I grinned in return, like an idiot, and felt myself turn hot with embarrassment. She grinned back, displaying her perfect bright, white teeth. Perhaps she was a witch, but I didn’t care.

Our coming together was almost comical. She was carrying a small, wicker basket, with the remnants of flatbreads and olives in it, and, as we drew close, she missed her footing on the rough ground. Falling towards me, I held out my arms, as the basket’s contents flew hither and thither. How I caught her, I’m not sure, but catch her I did. And then we just stood there, holding tight, breathless and silent – at least for a moment. For all I knew or cared, the universe itself had gone away, and we were all that remained in the whole of creation. I eased my hold on her, and we stood face to face. Then, we talked.

Her name was Mariam, and she lived with her parents, and her brothers and sisters, in one of the houses. Although only fifteen years old, she was already betrothed to a man over twice her age. A good man, by all accounts, a carpenter by trade, upright and decent, but not Mariam’s choice. It was the way of the world – her world, that is. In my turn, I told her about Sidon, and the fishing boats bobbing, and the trees, and my childhood friends, and my bow and arrows. I kept quiet about army life, since I didn’t think it suitable for her young ears. We laughed together, held hands, and promised we’d meet somehow, that night. The place was agreed – a certain hill about a leuga and a half behind the houses, where all would be quiet. It was a kind of madness, of course, and we both knew it, but that year everything was mad, almost as if a craziness had spread across the land like a disease: power craziness, god craziness, blood craziness.

I sneaked out of camp at ten in the evening. A clear sky, with a dazzling canopy of stars to light my way. It took me about an hour to reach the appointed spot, where I sat down on the slightly damp earth, and waited for Mariam. It wasn’t too long before she arrived, although how she managed to get away from the family was beyond me. Perhaps she really was a witch. It didn’t matter. Nothing mattered. We kissed, embraced, made love, and lay beneath the heavens. Hardly a sound was made; hardly a word exchanged. She smelled of honey, and fresh air, and some sort of perfumed oil – Frankincense, I think. Then, I walked her back to the house, squeezed her gently, and returned to base, with a spring in my step.

After that, I only saw her once, and even then from a distance. We’d received news that one of Judas’ co-conspirators had been spotted south of the Sea of Galilee, and a group of ten of us were sent to the area. A wild goose chase, as it turned out, but the route took us via the unnamed hamlet. As we marched past the houses, Mariam was standing in her doorway, almost as if she was expecting me to pass. As I tried to catch her eye, she did something which all-but pulled me apart. With her right hand, she stroked her belly in a circular motion, and then she glanced at me, and half-smiled. I knew – just knew – what that meant, but there was nothing I could do.

Two weeks later, and quite without warning, I was transferred to Numidia. Maybe I was being punished for my indiscretion, although it was more likely just one of those things. I’d signed up, knowing I might be moved to anywhere in the civilised world, wherever the Empire required my particular skills, so I didn’t complain. If anything, Numidia was hotter than Palestine-Judea, but not so mad. Nowhere was as mad as the country of the Jews. They had a gift for it that went beyond the merely insane.

Over the next forty years, I fought, in Rome’s name, across so many different provinces: from Numidia to Mauretania Tingitana; from Baetica to Gallecia; Aquitania to Belgica; Noricum to Macedonia, and so on. I encountered strange lands, stranger peoples, peculiar tongues, beautiful women, and so many different wines. I lived a full life, while destroying hundreds of others. It was my job, after all, to defend everything the Empire stood for. During all this time, I heard rumours concerning Mariam and her child – our child. Army gossip, really, passed around from legion to legion, like so much fluff and tittle-tattle. According to one tale, she gave birth to a son, and the family connived with her betrothed, and passed him off as the father. Another had it she was banished from her home, and sent into exile in Aegyptus, where the child was raised unto manhood. I preferred the first tale, since it soothed my guilt a little. Either way, there was nothing I could have done, or can do, and being of a stoical disposition, I let it lie… until I officially retired from active service, that is.

Over the last five years, finally rooted in this harsh place, with its harsh language and harsher people, I’ve tried my best to find out the truth about ‘my’ girl and her boy. There’s little else for me to do here, in Germania Superior, on the edge of the world, except think and puzzle. A madman, every bit as crazy as Herod, now rules the Empire, and I know that truth is a variable commodity, dependent on all manner of things, and I doubt I’ll ever glean anything for certain, but there are several competing and complimentary legends I’ve come across, concerning Mariam and the child. One has him growing up to be a carpenter, like his ‘dad’. Another has him as a fisherman, of sorts. Then again, there are stories of how he belongs to a secret desert sect, healing people of their ills, both of the body, and of the mind. I like this story, since it balances out the death and destruction I’ve caused in my life – an atonement, of sorts. There are other tales, though, which concern me greatly. Growing up in Aegyptus, he was trained in the magical arts, and etched from head to toe with potent images, so that when he returned to his homeland, he was much feared by his superstitious, reason-addled, fellow countrymen. In a similar vein, he might have become a political trouble-maker and rabble-rouser, stirring up the people against their priests, and – worse – against Rome itself. I hope this isn’t true, since I know full well how severe the punishment would go. Execution, Roman style, is a ‘hung out to dry’ terrible thing. As for Mariam, I’ve learnt nothing. A vacuum of knowledge is all there is. I hope her life was, and is, a contented one. I hope she loves her son. I hope she forgave me – forgives me, my trespasses. I loved her, in my way, as fully as I could, and I’ve never forgotten her.

When I’m dying, which will be soon enough, I know, with absolute clarity, whose face I’ll see in my dreams. It will be Mariam all the way. Her black eyes, her mouth with a half-smile; her perfumed body and honeyed breath, and the tight, pulsating heat, as she wraps herself around me, drawing me in, and home. And that will be enough to ease my passing. It will be sufficient.

A solitary truth, then. At the last.

.

Dafydd Pedr