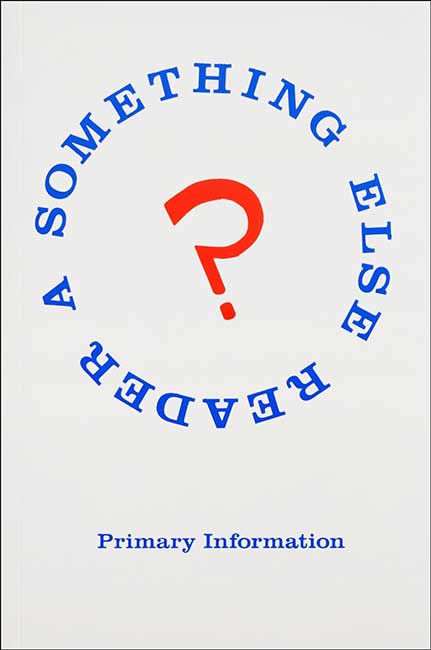

A Something Else Reader, edited by Dick Higgins (1972) and Alice Centamore (2022), Brooklyn, NY: Primary Information, 2022. 368 pages.

Primary Information, based in Brooklyn, NY, have a project of republishing or reissuing works that are out of print or otherwise unavailable. In particular works of the twentieth-century avant gardes linked to underrepresented groups, and at the intersection of politics and aesthetics.

The organization’s programming advances the often-intertwined relationship between artists’ books and arts’ activism, creating a platform for historically marginalized artistic communities and practices. (‘About’, primaryinformation.org)

This publication is a realisation of a project planned and proposed by Dick Higgins in 1973/74, but never brought to press. The editor Alice Centamore has constructed the Reader based on detailed plans outlined by Higgins, and drawing on her extensive research into Something Else Press and Higgins’ other work. Primary Information have previously re-published other books from Something Else Press, including Williams’ Anthology of Concrete Poetry, Fantastic Architecture (edited by Higgins and Wolf Vostell), and the Great Bear Pamphlets. Part of their overall project is a support of conversation with earlier practices:

Primary Information facilitates intergenerational dialogue through the simultaneous publication of new and archival books, providing a new audience for out-of-print works and historical context for contemporary artists. (‘About’, primaryinformation.org)

This book thus operates as an exploration to varying degrees across subjects of research scholarship, literary history, avant garde studies, anthologising, book design and construction, and editing. This variety echoes the range of content and form in the book’s contents, and the varied routes to physical presentation in book form. This is further apparent in multiple typefaces and letterforms, layouts and page designs of as the contents replicate their original presentation in Something Else Press publications between 1963 and 1973.

Higgins’ project, offering a survey or sampler of the work of his press, also suggests a pedagogical or informative purpose. A reader, echoing projects such as Walt Whitman’s American Primer, or Ezra Pound’s ABC of Reading, has a role in forming a readership, in building an audience, in training or teaching potential readers. This educational or market-building purpose may have been at the forefront of Higgins’ thinking as Something Else Press struggled financially throughout its history, and Higgins often commented on the need for greater impact, wider distribution, better reach to the readership he was confident was out there for the work he published.

My intention hasn’t changed at all: to publish what nobody else knows how to handle, the new forms that aren’t labelled, the useful science books that aren’t dull enough for professionals or hip enough for the establishment. Whatever the establishment would do, I would do something else. If they mis-published something, I would do it right: and mostly I would concentrate on things that could not find another publisher. Things that just weren’t neat, but which seemed to me to need their audience, that seemed natural in our world. (Higgins, Introduction, 11)

An anthology or selection such as this also works to create a family, an association of writers and artists who are gathered between its covers, who are put into relationship with each other through their being listed or presented under the heading of ‘a Something Else writer’, one of ours, they belong together. Anthologies perform a taxonomic or categorising function, not in this case along national or genre lines, but in terms of an approach, a relationship to language and words and writing. Higgins’ press brought together writers and artists from across the US and beyond, artists linked by practice and events, by declared association through belonging (in varying degrees) to the Fluxus group, or being part of the Happenings in New York, or being identified (by Higgins) as related to or having an affinity with the current avant garde. The Reader includes event scores by Alison Knowles, notations for sound works by Pauline Oliveros, a photo-story by Carolee Schneeman, an essay on chance by George Brecht, concrete poems by Ian Hamilton Finlay and Augusto de Campos, and a planned TV schedule by Nam Jun Paik. The earliest work included is part of William Brisbane Dick’s 100 Home Amusements, originally published in 1873. Gertrude Stein is another earlier writer published by Something Else, and the Reader includes an excerpt from ‘G. M. P. and Two Shorter Stories,’ (1933) published by Higgins in 1971.

I always admired Stein and had a fairly good collection of her works. But I never thought that I or any of my colleagues at the Press had anything to do with her in terms of what she or we were about. […] Accused of being a Steinian disciple more or less, I decided to make available all the Stein works that were out of print and in the public domain […]. (15)

Higgins through making more widely available Stein’s work in the late 1960s and early 1970s did significant work in introducing her to a new generation of writers including those who would be later labelled the Language School. In this act of making hard-to-access work more available the parallels between publishers Primary Information and Something Else are evident.

The notion of a school or movement was resisted by Higgins, and by the work of the press, though he certainly intended for these disparate authors to be understood as having some connection beyond the accident of time and place or the whims of an editor. The Reader would further promote the work of Something Else, and would more widely disseminate the kinds of innovative and experimental work these writers were making. Higgins initially intended for the Reader to be produced by a mainstream trade publisher, and sent a detailed proposal to Random House. He believed this was literature that could and should have a wider general readership, and was resistant to elitist or specialist perceptions of avant garde practice. Higgins’ intention with projects such as An Anthology of Concrete Poetry, edited by Emmett Williams, was to present artwork to a wide audience. In also trying to keep prices low, maintaining a close connection between editing, design, production and distribution, the Press was part of a wider art movement that resisted commercialisation for profit, but recognised the need to earn a living from making art. Over the decade and a bit of its operation Something Else would always walk a tightrope of financial instability and overwork for the core team. At one stage Something Else Press became part of a co-op and worked within this model to distribute their publications, but the focus was elsewhere and for Higgins the model didn’t support the making and selling of his books.

So the more books we did, the less money we got. The more the salesmen “sold,” the more we got in hock with the distributor, to cover postage, salesmen’s commissions, etc. (16)

In a market that could easily become insular by following sales, Higgins’ work brought writers and artists from across the world together between Something Else covers, some of these were linked by involvement with Fluxus, some though contemporary art distribution networks, some through participation in events and festivals. Recognising their potential to inspire or to offer models for making, Higgins published them, and then wanted to further extend their influence via this anthology. In his ‘Checklist of Books from Something Else Press’ included here (323-248) Hugh Fox in summing up his own project, gives a suggestion of how readers might encounter and engage with this Reader, it:

serves as a summing up of a whole century of artistic theorizing and practicing, and as a kind of book-stall where the prospective reader can browse until he finds a book that invites him into the world of Something Else. (324)

Mark Leahy