Tish Murtha’s relentless vision can be characterized by a single trait: empathy. She unflinchingly investigated forsaken communities crippled by ineffective government policies and bleak living conditions.

Despite her notable output — powered by an active home darkroom — her work went underrecognized throughout her life and after her sudden death in 2013. Last year, her daughter Ella spearheaded an online campaign to publish a limited-edition book based on Murtha’s series “Youth Unemployment.” She is now having her first retrospective, “Tish Murtha: Works 1976-1991,” on view at The Photographers’ Gallery in London through October 14.

Gordon MacDonald, the exhibit’s co-curator, deemed Ella the “driving force behind the rediscovery of her work and archive” (Ella herself was blunt as to why her mother had been overlooked for so long: “Because she didn’t have a penis”). This was, Mr. MacDonald said, “a very direct and plausible argument to explain this historic lack of visibility for Tish, and many other female artists and photographers.”

Born in 1956, Murtha grew up poor in a family of 10 children in an industrial area of England near Newcastle. It mainly offered a treacherous future in mines or munitions factories, and even those professions were plagued by mass layoffs. The sense of stasis and struggle that permeated Murtha’s series reflected, as Lynsey Hanley wrote in the companion publication to the exhibition, “a sense of society’s resources having been so misdirected, so wasted.” Children played amid debris and abandoned cars; brick buildings crumbled as if they had been hit by a modern-day blitz.

Informed by her social conscience and own working-class roots, Murtha was eager to highlight these disadvantages. She felt it her duty to “stay in the margins … and advocate for the people she grew up with” by chronicling and exposing this bitterly difficult context, Ms. Hanley wrote.

Poverty was so dire that it resembled turn-of-the-century living conditions rather than England on the cusp of the millennium. The revelation of these alarming circumstances yielded some action: Her 1978 “Elswick Kids” series led Murtha to a government-funded position as a community photographer in Newcastle, and in 1981, her work was directly addressed in the House of Commons. While her photos reveal Thatcher-era Britain, Mr. MacDonald compares them to contemporary scenes of legislative failures and rising social inequality. “Remarkably and disturbingly, the work has a real resonance with the effects of current political decision making and of sustained austerity,” he said. “Poor people suffer for the economic failure of governments, and to support the rich.” Class, he added, is “another way of describing economic and cultural control.”

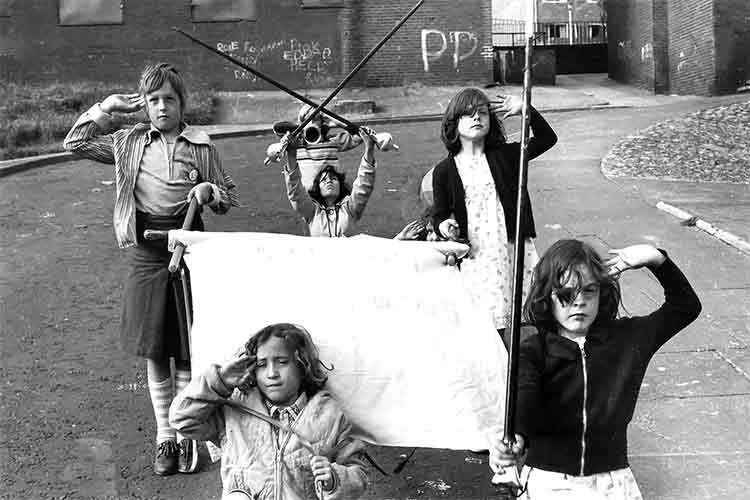

From “Youth Unemployment.”CreditTish Murtha/Courtesy of Ella Murtha and The Photographers’ Gallery

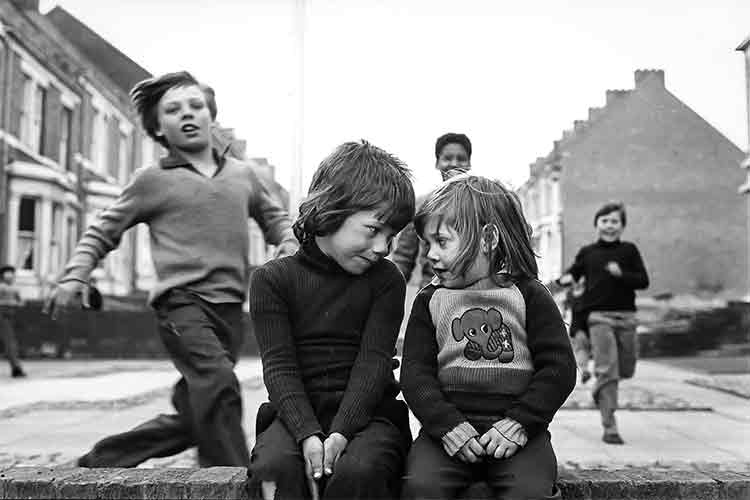

From “Youth Unemployment.”CreditTish Murtha/Courtesy of Ella Murtha and The Photographers’ Gallery

Despite that sense of purposelessness, her work tenderly celebrates resilience. The value of companionship and the cushion of a strong local community is evident, be it in the embrace in a 1976 photo entitled “Angela and Starky,” or the sweet gaze shared between two children in a photo from the 1978 “Elswick Kids” series.

After taking a night course in photography, Murtha studied at the School of Documentary Photography at Newport College of Art in Wales. David Hurn, a founder of the program, interviewed her during her entrance exam; when asked about her interest in photography, she delivered this notoriously sharp-tongued retort: “I want to learn to take photographs of policemen kicking kids.” Mr. Hurn, impressed, not only admitted her but later acted as guarantor on the purchase agreement for the camera she used in her work.

“It would be a cop-out, and even classist, to say that Murtha was a natural,” Ms. Hanley wrote. “It is clear that she knew what she needed to say and worked as hard as she could to perfect that message.”

The exhibition features her major projects and outlines the editing process behind her stories. Her work evolved, but “maintained its central drives: rigor and empathy,” said Mr. MacDonald. “She felt photography could reveal inequality and offer some visibility to those left behind by the political decisions of the time.”

Her earliest series, done while in school, was a study of the regulars of The New Found Out, a traditional, working-class “spit and sawdust pub,” as Mr. MacDonald put it. “Juvenile Jazz Bands” (1979) documented the ragtag bunch of children rejected from other marching bands who practiced in deteriorating lots yet wielded batons like exuberant young wizards. “Youth Unemployment” (1980) — her best-known series — put the spotlight on a generation fitfully biding its time, unsure how to eke out a future among diminishing prospects. Those photos centered on her brothers, friends and neighbors.

“There was a cool youth culture in the ’70s and ’80s, just as there is a derelict one now,” Mr. MacDonald pointed out. “It just depends where one decides to look. I think that Murtha was far more interested in those with no choices than those who felt able to financially or culturally make them.”

In 1981, Murtha moved to London where she was commissioned to create a series on Soho’s sex industry for the 1983 group exhibition “London by Night”; her images of furtive men and dimly lit women were paired with texts by a dancer and stripper named Karen Leslie. Her final series in the exhibition, “Elswick Revisited” (1987—1991), explored the way the region had changed and the creep of racism.

Mr. MacDonald noted that as idolized cult British bands “were playing in London to people wearing knee-high boots and antique military dress tunics,” Murtha stayed focused on the margins. “Poverty is just harder to look at and sell than glamour,” he said, “and is only made apparent through photography when people like Tish work hard to show it.”

Follow @nytimesphoto on Twitter. You can also find Lens on Facebook and Instagram.