Room to Dream, David Lynch and Kristine McKenna (Canongate)

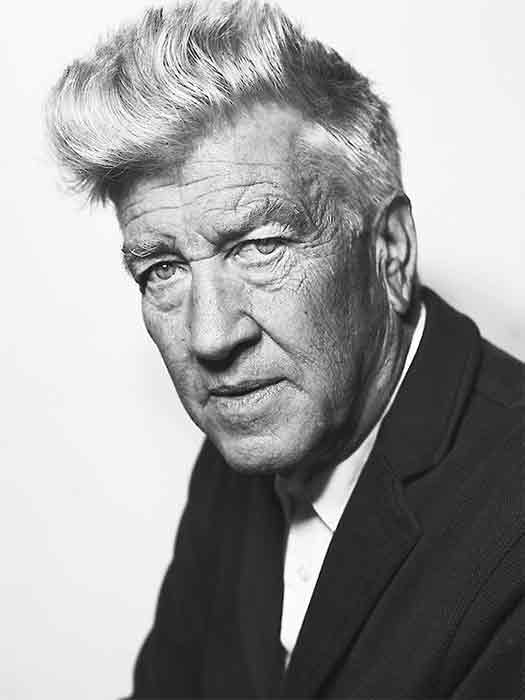

Room to Dream is, dare I say it, a very Lynchian version of a biography or memoir. Kristine McKenna writes a chapter by chapter account of David Lynch’s life, and Lynch writes back to each chapter in a new chapter, giving his version of events, his – sometimes very different – take on things, explanations and overview.

It’s a brilliant idea and makes for entertaining reading. McKenna uses traditional research and interviews to tell a straightforward version of events, which Lynch then subverts. As in many of Lynch’s films, it seems that the smalltown world Lynch grew up in hid some dark secrets. And Lynch was clearly single-minded, obsessive and wayward pretty much from the word go: once he had decided he was going to make films, then that was what he was going to do.

Early life for Lynch appears to have been a kind of endless summer, with friends, family and girlfriends in orbit, but pretty soon it appears Lynch had many different groups of friends, was playing women off against one another, and only got married to his first wife because she was pregnant. He dithered with art schools in America and Europe and wound up in LA at a film school, where in his second year and beyond he made Eraserhead, taking over disused garden buildings at the school as a makeshift studio, obsessively working nights and sleeping days, doing odd jobs to keep funds coming in, and breaking up his marriage in the process. Eventually, Eraserhead got picked up by a distribution company who specialised in word-of-mouth cult films, and Lynch’s erratic artistic journey really began.

It’s also this early in Lynch’s life where his interest and participation in Transcendental Meditation starts, seeming to both calm and energise his progress through life. The Elephant Man came about principally because of support from Mel Brooks (!) and was a quick lesson for Lynch about how big film companies worked. Based in London he worked with John Hurt, Anthony Hopkins and other to produce a quirky mainstream film, before becoming entangled in the critical disaster that was Dune. In retrospect of course, Dune is not as bad as everyone said, it just didn’t fit in with 1980s ideas of what science fiction should be, and – of course – couldn’t quite capture the epic sprawl and political/religious intrigue of Frank Herbert’s book (or its sequels).

Somehow Lynch survived the critical drubbing and in 1986 Blue Velvet as released, to critical acclaim and cries of shock and moral outrage. It is here that Lynch’s world is truly made evident, a world of secrets, love and terror, that Lynch has continued to visit in films and the wonderful television of Twin Peaks, not to mention in his photography and other artworks. It is this singleness of vision, the self-assuredness and commitment that most comes through this book. McKenna details the evidence and events, Lynch responds with how he felt, why he did things, what he was thinking and what he hoped for. It’s an entertaining and illuminating read, entirely appropriate to the wayward genius of David Lynch.

Rupert Loydell