There is a poem that goes:

“Arrived

Immigration

Interrogation

Detention: detained, imprisoned

Group 4: abuse, threat, discrimination

Case: adjudicator, hearing, appeal dismissed

Meanwhile: abuse repeated, threats

Fed up: protests, demonstrate

Arrested, interrogated, charged

Court, magistrate, solicitors

Remanded, suppressed, but supported

Court, adjourned, Crown, barristers, court case

And still

They continue to remind me of

Horrors faced back home”

Written by one of the Campsfield Nine – a group of detainees charged with “riot and violent disorder” in 1997 – it narrates the personal experience of entering the UK in search of safety, only to encounter endless state violence inside and outside of detention.

Early one morning in Campsfield detention centre, 1997, detainees were awoken by the cries of pain of a man whom guards were preparing to be taken to the airport and forcibly removed from the UK. One man caught sight of a fellow detainee being strangled by a guard, and news spread throughout the detention centre. Within two hours, over 50 detainees had gathered to chant and cry for “freedom”, to protest how their basic human rights were being ignored and violated by the British government. Group 4 (now known as G4S – known for its security contracts with the Israeli government, the murder of Jimmy Mubenga, exploiting prisoner labour) staff purported that during the protest, detainees destroyed the kitchen, looted the shop, and set ablaze the library. In allenged response, Group 4 guards donned their riot gear, and brought in police officers with dogs and riot squads with shields and batons.

Subsequently, nine West Africans – the “Campsfield Nine” – were picked out, arrested, charged with “riot and violent disorder”, and transferred to traditional prisons. Having already been held for several months in detention, the majority spent the entire nine months in the lead up to the trial in prison – and, if found guilty, they faced up to ten more years in prison. Three of the nine were teenagers, whilst seven were claiming asylum as environmental activists or political opponents of the Nigerian or Ghanian government. Back in West Africa, many had been imprisoned and brutally tortured for their involvement in the Ogoni movement opposing Shell’s colonial exploitation of their land – which left many murdered by the military (financed by Shell), or executed by the Nigerian state.

As the trial began, it became evident that there were clear contradictions within the stories of the Group 4 employees that had been present on the day of the protest. Guards invented vivid stories: Caryn Mitchell-Hill claimed that she had been alone in a corridor when a detainee grabbed her by the shoulders and shouted “where are you going you white bitch?” – only to be shown in court CCTV footage of herself at the same time in a different area with two other guards. Another Group 4 Employee, Chris Barry, claimed to have been repeatedly beaten and punched to the point where he became “concussed”, his shirt soaked by chemicals thrown at him. During the trial, CCTV footage showed Barry, a few minutes after he claimed this happened, walking on the roof visibly clean, dry, and untouched. In addition to providing conflicting testimonies that undermined their own narratives, two guards admitted to hitting detainees on the head (rather than on the arm, as trained) with batons. Eventually the trial collapsed, as the Crown Prosecution Service withdrew its evidence, and the Campsfield Nine were deemed “not guilty” in 1998.

Consequently, one (teenager) of the Campsfield Nine was transferred to a psychiatric unit after trying to commit suicide after 13 months in custody. Three were given refugee status or leave to remain (demonstrating the stupidity of their detention in the first place), and five were detained or sent back to Rochester prison pending deportation from the UK, as the prison-industrial complex and Home Office continued to work side by side. Five days before the start of the trial, the immigration minister at the time, Mike O’Brien, visited Campsfield to present Group 4 with an Investors in People award, whilst detainees were on hunger strike.

I retell this story not simply to reinforce how G4S is an inherently violent company that employs racist abusers with destructive tendencies, but that there has always been a long history of protest and resistance from inside detention. Increasingly, this is coming to the forefront of struggles against detention, expressed in many different forms of direct action. The end of March this year saw women detained at Yarl’s Wood detention centre collectively organise themselves, gathering and refusing to be separated or taken in preparation for a charter flight to Nigeria and Ghana – ultimately ensuring that no women were forcibly removed that night. As groups and individuals, detainees regularly protest their conditions – going on hunger strike, occupying yards, waving banners with messages for those on the outside, wearing customised t-shirts proclaiming “we are not animals”, and resisting deportations.

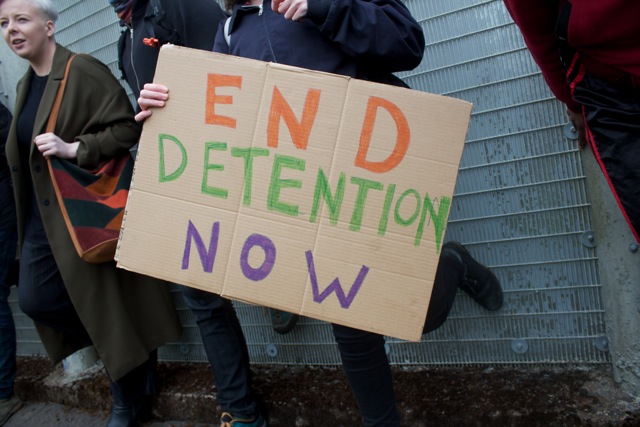

There is a power and a strength to resistance enacted by detainees that will never be able to be produced in such force by those on the outside who lack lived experiences of detention. Therefore, the movement against detention must be led by those who feel it most acutely, who face emotional and physical state violence every day. It is up to people on the outside to facilitate the conditions within which the feelings and experiences of those inside detention are listened to, and placed at the forefront of resistance. This was one objective of May 7th, a transnational day of protest against detention centres and show of solidarity with people in detention, which saw demonstrations take place at detention centres across the UK, and in Belgium, Calais, Germany, The Netherlands, Iceland, Spain, Greece, Sweden, the U.S., and on the Austria-Italy border. Initially called by groups Leeds No Borders and Movement for Justice among others, May 7th sought to protest the conditions of and show solidarity with the 30,000 adults and children who are detained against their will under the Immigration Act every year in the UK – without judicial oversight, or adequate access to legal support, translation, and healthcare. The day is part of a wider transnational campaign to end the inherently abusive and violent system of immigration detention that criminalises, detains, and imprisons people simply because they have chosen or been forced to migrate, as described first-hand in the poem this article begins with.

The expanding detention estate in the UK is primarily run by private companies such as G4S, Serco, and GEO, who directly profit from the outsourcing of violence by the state, through the imprisonment of people deemed to be “illegal” by governments. Detention centres are rarely discussed in the media or on the street, with the Home Office banning the UN’s special rapporteur on violence against women, Rashida Manjoo, from entry into Yarl’s Wood – but May 7th aimed to bring to public attention their existence and the dehumanising conditions for people imprisoned within them. Along with the continual physical and sexual abuses of detainees by detention staff and Home Office employees, there have been over 2,200 attempted suicides since 2007 (an all-time high), and 26 deaths across the UK detention estate since 1989 – showing the devastating effects of detention on physical and mental health. Despite claiming not to, the Home Office consistently ignores its own guidelines and detains pregnant women, children, and survivors of torture – which often go unchallenged by the non-profit industrial complex who rely on the benefits of having good working relationships with the state. Rather, these charities often reinforce the agenda of the state – such as the charity Barnardo’s role in the detention and removal of children.

Unlike campaigns calling for a time limit to detention, the resistance of May 7th objects to the very existence of detention centres, situating it within the wider geopolitical context of state borders and the exploitative conditions of capitalism that determine who is able to move freely. Actions took place in solidarity with wider struggles against border and migration controls, and with people who are living in detention without walls – who are unable to name so clearly what it is that stands in the way between them and what it is they need and/or desire – from Calais, to Idomeni, to Tangier, to Arizona. The detention estate, and act of detaining people without certain documents, is part of a much bigger picture – and it is potentially dangerous to think that detention exists as something only experienced within the four walls of the detention centre – regardless of whether it is the sole focus of a campaign or not.

For example, think back to the activists who fled Nigeria because of the torture they experienced as a result of their campaigning against Shell, the company committing genocide in Africa by destroying the environment of native cultures, and having those executed who resist. These stories demonstrate the clear relationship between Western governments and corporations, and the reasons people may be forced to migrate and seek asylum, ending up in a society that has already accepted (and directly profits from) the hegemonic power of corporations that plunder and exploit the resources of both people and the environment. A memo, written by a spokesperson for Shell Nigeria, reads: “For a commercial company trying to make investments, you need a stable environment; dictatorships can give you that.” Western governments and corporations have put in place power dictators all over the world, in order to create and maintain a business-friendly environment, whilst eradicating any resistance. Because the pursuits of corporate capitalism know no borders, any movement that seeks to challenge this, and the dominating political systems of imperialism, white-supremacy, and patriarchy that intersect, must be transnational.

At the same time, decisions related to the lives of people who choose or are forced to migrate are being increasingly determined by the priorities of capitalism. In the UK, the companies that run detention centres are making immense profits, able to employ detainees to work for as little as £1 an hour. Countries in the EU cooperate in detaining and deporting people, whilst the EU itself mediates relationships between nation states, corporations, and individual’s lives. For example, the EU Directive of 2001 defers the task of judging who is understood as a “refugee” to the staff of corporations such as commercial airlines, who will inevitably make any decisions based on the priority of profit.

The clinical, controlled, and systematic (or at least trying to be – anyone who has experience of the Home Office knows how arbitrary they are in reality) nature of the detention estate and deportation regime in the UK must be connected to the chaos and disorder of border regimes further afield, “refugee camps” riddled with corruption, and pushbacks by border guards and police. They’re two sides of the same coin, part of the same imperialist, capitalist system of exploitation that creates and reinforces the existence of borders. If detention is a vital part of the deportation regime – more than a holding cell for those facing deportation, and rather a mechanism of state control – then it must be challenged in solidarity with worldwide struggles against global borders – because leaving the four walls of detention doesn’t necessarily mean that you are free, or can even begin to imagine living freely.

I received an email from a friend two months after he was deported from the UK, to a country in which he had experienced torture, leaving permanent scars spanning his body and mind. He had been labelled a “foreign national offender” by the British government, deported for the conviction he held for using documents that were not his to travel to the UK. Accordingly, he was criminalised for his desperation to escape the violence he had experienced, and for his attempt to survive the situation he had been forced into by the Home Office, of not having the “correct” documents. In the email he wrote to me, he said: “I really want to be there for my son [who lives in the UK]. We don’t want him to grow up without his father.” As one ex-detainee states in Detention Without Walls, a film produced and led by people with lived experiences of detention: “If someone’s kids live on one side [of the world] and you put them on the other side, sooner or later their relationship is not going to last”.

For many, detention is not the final destination: deportation is – a constant threat to anyone who is not a British national in the UK (and increasingly, British citizens too). Although he left detention, after being deported from the UK my friend is still being held in a state of detention, in a country he was tortured in and holds no ties to, far away from his partner and growing child. Certainly, detention stretches beyond a physical building, a holding cell: closed doors, gates, and tall fences morph and elongate, spread themselves out flat and unravel into threads that reach coastlines, enter country exit and entry signs, cover highways filled with trucks of bodies and beaches of discarded life jackets. These parameters bridge catchment areas, possessing the power to determine where someone can go to school, where they can access healthcare, and ultimately, where they can choose to exist. As one ex-detainee states in Detention Without Walls: “rather than fences and gates [detention is] more a sort of mental incarceration.” Borders are simply a different form of imprisonment, a more accepted, more ingrained substitute to the detention centre: locked doors and wire fences are replaced by economic inequalities, uncooperative coastguards and stormy seas, a suspicious flight attendant – not only affecting physical spaces, but social relationships too.

For people with nationalities other than those of the overdeveloped countries, detention can be everywhere; I cannot claim to know how it feels, but friends tell me that it is the extra seconds a border control official may take to look you up and down, it is the sight of police on your road, it is being asked for proof of nationality by your landlord. I have another friend, who grew up in North Africa with little opportunity to study. He found a job, and saved up enough money to travel to Europe to study and work part-time. There, he made friends, practiced foreign tongues, fell in love, learnt to cook, fell out of love, and – there’s no better way to put it – lived. When his studies came to an end, he faced deportation to a country he hadn’t lived in for years, a culture he couldn’t remember, and a family that firmly practiced a religion that he no longer believed in (note the process that benefits the West every time: acquire cheap migrant labour, convert from Islam, deport). Understandably, he didn’t want to claim asylum and face the prospect of detention and probable deportation. He was stuck: he couldn’t leave, but he couldn’t stay. So, left with no other choices, he went underground – left without access to stable work, a home, or public services such as education or healthcare. Whilst the detention centre is a place in which the state has total power and control over your disciplined body and mind, for some people (often the same people who are held in detention centres), your body and mind are being disciplined everywhere you go.

Furthermore, being released from detention is not akin to feeling free. Throughout Detention Without Walls, there are persistent feelings which can be understood through one ex-detainee’s assertion that: “You’re basically in prison but you’re out here”. The film draws attention to how, if released from detention, a person is unable to work, will struggle to access education and healthcare, must live on food vouchers, may face destitution – and if housed cannot choose where in the UK they can live – regardless of where their existing family may be/the roots they’ve put down in a place. Still subject to the oppressive powers of the Home Office, one ex-detainee describes the difference: “The murder happens inside detention… But they let you die outside.” Not only are those released from detention affected in a practical sense, but psychologically and emotionally too, culminating in the feeling that, as one friend described it: “You can leave detention, but detention may never leave you.” There exists a lack of emotional and psychological support for those who are released from detention, as doctors increasingly prescribe anti-depressants to many for whom “depression” is a rational response to the oppressive political and social conditions they inhabit, and the state violence they have encountered in the UK (let alone, if they are seeking asylum, the country they have fled from).

As the UK government faces increasing criticism over detention centres, policies such as “deport first, appeal later” will be rolled out in relation to all immigration appeals (but not asylum) based on human rights grounds, as part of the new Immigration Bill – perhaps suggesting that the UK government may be searching for new ways to discipline people who choose or are forced to migrate – which do not rely so heavily on the role of the detention centre. Rather, people with the right to appeal decisions made by the Home Office will be deported before this appeal can take place in the UK – potentially resulting in les time spent in a detention centre beforehand. Certainly this can be seen in respect to Jamaican “foreign national offenders”, as a £25 million-pound prison is being paid for and built by the UK government – meaning that people who have spent most (or all) of their lives in the UK may serve criminal sentences in Jamaica, for crimes committed in the UK. As discussed earlier, border and migration controls are increasingly tightening, making it even more difficult to reach Fortress Europe safely – and therefore extending the function of the detention centre to places further afield, affecting someone migrating before they may even reach the UK. In addition, it will not only become harder for those inside detention seeking release, but the brutal conditions on the outside can be felt more acutely: the Immigration Bill plans to withdraw support (money and housing) entirely for families whose asylum claims are refused, therefore forcing more families into destitution.

However, across the world, people inside and outside of detention are fighting back, challenging and organising around borders and the demand for free movement for all – through direct action, monitoring state authorities, and literally crossing borders – and May 7th formed a clear part of this. It may be too early to tell yet the after-effects of the day, but the Surround Yarl’s Wood demonstrations, organised by Movement for Justice, have shown how these moments are incredibly powerful and have long-lasting effects – not just for people outside detention – but for those inside detention, who may find strength in the faces and voices of those trying to reach them, such as the women mentioned earlier in Yarl’s Wood who collective resisted a charter flight. If momentum continues, May 7th will be able to have long-lasting effects, particularly as it was a day of protest and solidarity that itself disrupts borders and builds support between transnational groups. It brought the detention centre into public spaces of discussion, as an issue for which everyone holds responsibility; detention may not necessarily directly affect people with British citizenship, but they are undeniably the product of a culture for which we participate in daily.

I spoken detainee after the demonstration at Dungavel detention centre; he told me: “It’s okay for you – you get to come here for a few hours, feel good about yourself, and then go home. But I’m still here.” The struggle against imperial, capitalist borders and the control they exert has to continue once we’ve left the grounds of the detention centre, once we can no longer see the faces of the people locked inside, or hear their calls. It is up to people on the outside to make sure that these faces are seen, and that these voices are listened to. Abolishing detention isn’t the end of the fight, but it’s a vital step in making sure that the whole world doesn’t become one big detention centre.

Lotte Ls

Photographs by @Etza_Hdez