Sophie was asleep, curled up on the settee, the head of her favourite unicorn pressed close to her face. I didn’t want to disturb her, so I went into the bedroom as soon as my mobile started to ring. It was Sam. He asked me, had I noticed anything strange about Sophie recently? It was a strange question for an absent father like Sam to ask, I thought, but I didn’t say so. I just said no, which was the truth. Run your fingers across her forehead, he said. I can’t right now, I said. She’s asleep on the settee, curled up with Roxie. I don’t want to wake her up. Who on earth’s Roxie? he said. Her favourite unicorn, I said. You should know that, you’re her father. Well, do it when she wakes up, he said. Check if it’s smooth. What are you going on about? I said. This unicorn thing, he said. She could be turning into a unicorn. See if you can feel a horn growing in the middle of her forehead. I jabbed the phone, cut him off. I can do without him phoning me up, taking the piss.

A few minutes later, the phone rang again. It was Sam. I thought, should I or shouldn’t I, then answered it. I wanted someone to talk to and arguing with Sam was better than nothing. It passed the time. He carried on where he’d left off. I’m being serious, he said. Kids are turning into unicorns. Yes, whatever you say, Sam, I said, in my tired, fuck-you voice. Goodnight.

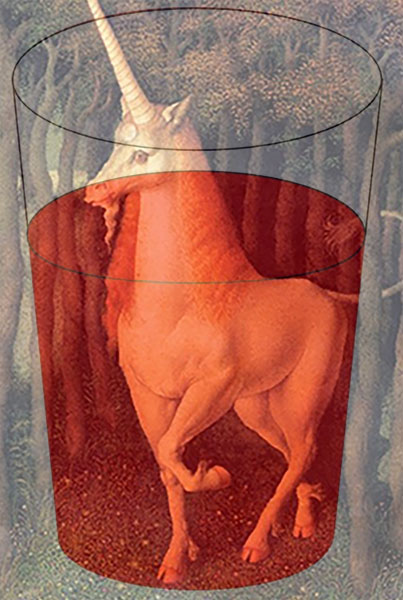

I didn’t believe a word of it, but I googled it nevertheless. It turned out, of course, that he hadn’t made it up. There were stories out there. There were pictures, video clips even. It’s so easy to fake stuff, though: to take it all at face value you’d have to be as stoned as Sam was most of the time. It was all just too stupid for words.

By the following morning, though, it’d hit the headlines. It wasn’t just an internet rumour: it was official. Children were turning into unicorns. Nobody knew quite what to do about it. We were told not to panic. A journalist with a microphone standing outside Number 10 said he understood the government COBRA committee were meeting later that morning. Plans would be made. Guidance would be issued. Days went by. Advice sheets came in the post and posters appeared on school gates. It told you what you could do to reduce the risk (not a lot, at that time) and what to do if your child turned into a unicorn. Otherwise, life went on as normal, at least round our way.

About a week later, the government started publishing a graph on the internet every day, telling you how many children had turned into unicorns. There was even a map of Britain, too, with unicorn hot-spots shown in red. Manchester, Newcastle and London were the worst hit back then. Leeds was blue, which was worse than green but better than red. We were dark green, which was just slightly worse than light green.

Everyone remembers those first few weeks. The government called in the army and got them to erect emergency stable blocks. It quickly became clear too that, within days, Britain would run out of hay. There was talk of imports, although other countries in Europe were facing the same problem. Unicorns need space to graze. Sheep farms were requisitioned for grazing and farmers compensated. It didn’t come to much, though. A few people were found grazing for their offspring-turned-unicorns, but many more weren’t. And then, even well-provided for unicorns often ran away. Most of them ended up grazing in parks or on the grass verges of ring roads and suchlike places. Many got knocked down (like they still do). One Tory MP found herself ridiculed for suggesting the government was doing too much: horses were less bother than children, she said, and surely everyone had space to graze a unicorn. Another suggested that if there were too many unicorns, and as they weren’t human beings anymore, perhaps the best thing would be to cull them. This, on the whole, was accepted with a shrug by older people, but greeted angrily by young people with families. Fresh advice was issued: if your child turns into a unicorn, don’t give it too many sweet treats like sugar lumps because it’ll rot their teeth.

I remember the first time I saw a unicorn (doesn’t everyone?). It was in the small play-area at the end of our street. It’s all grass, with a swing and a slide in the middle. There’s a privet hedge and a fence all the way round it, so the children can’t run out into the road. The poor thing was about waist-height, bright pink and glittery. It looked confused and agitated. It kept cantering from one side of the area to the other. Every now and again it stopped in the middle and tried climbing sometimes onto on the swing, sometimes the slide. It’s hooves kept slipping off the equipment and it kept almost falling over. Then it would whinny and start cantering around again. I kept my distance and kept walking. Everyone takes them for granted now, but it was frightening back then. I felt so sorry for it, though. It was obviously still a child on the inside and couldn’t understand why it didn’t have arms and legs like a human. That’s what it’s like for them, they say, straight after they turn. It takes them time to adjust. Luckily, Sophie never turned, but I heard other parents at school say how, when they do, if you can get close enough to them to look into their eyes, you can still see the child in there. I’m not quite sure what they meant by it, but that’s what they said. Perhaps it was just wishful thinking.

I suppose the unicorn cults started up about then. They claimed the children who turned into unicorns were special children. They went out looking for unicorns and started venerating them. They claimed the whole thing was nothing to worry about. We were privileged to be living through a very special time, they said.

As the weeks went by, the scientists began to find out more about what was going on. Children with unicorn toys, they decided, were the ones most prone to becoming unicorns. Parents were told to confiscate and destroy them. There was much talk about a batch that had been imported from the Philippines but, as we all now know, it was all unicorns. Worryingly, they discovered that once a child began to turn, but before the changes became visible, they could pass the condition on to other children.

Of course, I was worried about Sophie. One night, as she slept, I carefully withdrew Roxie from her grasp. I cut him up into tiny shreds and put him in the bin. The next morning I told her that unicorns were magical animals and you never know when a unicorn might be called away to the magic unicorn land and that, however much they love you and want to stay with you, when they’re called they have to go. I remember thinking it sounded a bit lame and I should’ve come up with a better story, but she seemed to accept it.

As time went on, scientists discovered that the condition only affected children under twelve. The sense of relief when Sophie’s twelfth birthday came round was palpable. It was around that time she told me that of course she knew I’d taken Roxie and thrown him in the dustbin. She never lost her love of unicorns, though. When she left school she was lucky enough to gain an internship at the local unicorn sanctuary. She still helps out there.

After a few years, the unicorns started having baby unicorns. Foals grazing on the roadside became a common sight. Talk about cute. There was talk in parliament about birth control for unicorns, but it never got very far. The scientists, though, finally managed to come up with a vaccine for humans. The unicorn cults were against it, but most people were all for it. When it was rolled out, parents queued round the block with their children at the vaccination centres. You still get the odd one – usually, kids whose whose parents refused to get them vaccinated – but, generally, children don’t turn into unicorns anymore. Politicians began to talk about ‘living with unicorns’.

As everyone knows, unicorns have magic powers. It’s said that a unicorn’s tears have healing properties. The unicorn cultists bottle them and sell them. The same goes for unicorn horns. At first, unscrupulous people took to sawing the horns off roadkill but as time went on, a black market for powdered horn developed, fed by sinister poaching gangs. And not only that, but, as unicorn numbers increased, people began to notice a change in the weather. There’s a great deal more in the way of fine drizzle than there used to be. Whenever you look up into the sky these days, the chances are somewhere you’ll see a rainbow.

Dominic Rivron

Picture amalgamation Nick Victor