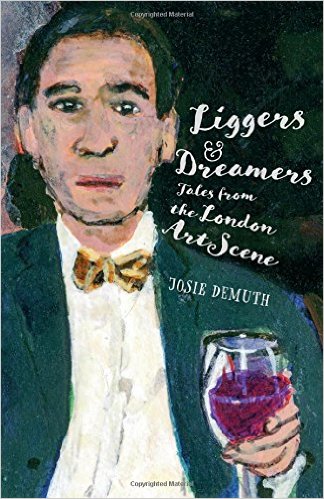

‘Liggers & Dreamers’ author Josie Demuth ‘on the lig’

‘Liggers & Dreamers’ author Josie Demuth ‘on the lig’

(for research purposes only) at the Venice Biennale

A REVIEW OF JOSIE DEMUTH’S LIGGERS & DREAMERS:

TALES FROM THE LONDON ART SCENE

By David Erdos

In Thin Man Press’s new publication, Josie Demuth artfully collects a representative body of skilled, if somewhat charmless objectionables, negotiating their way through contemporary art’s shallow waters. These waters do not deepen when the assorted Liggers are able to gatecrash the Venice Biennale Art Fair near the end of the book – where the renowned and scantily disguised ‘Koko Ono’ receives a lifetime achievement award – and indeed a life on the waves frames the end of the book where the various characters we have encountered along the way set sail from St Katherine’s Dock on a seemingly Fellini-esque soiree, along the Thames on board ‘the great ‘Cork Street Wino.’

It’s uncertain on a first reading whether the fourteen protagonists cleverly profiled at the start of the book deserve celebration, but perhaps that is the point. In focusing on the cockroaches who gather at the edge of the frame, the substance of the paintings and art that provide context for the stories and tales is smudged into soft focus. This reflects society’s current love of style over substance, what might be called the Ribena or even marshmallow culture, which has replaced a time when all the world was sharp fruit and stone-like gobstoppers.

Our reader’s eye is therefore encouraged to roam camera-like across incidents and connections between characters. Ms Demuth shows a Novelist’s eye can be matched to a Conductor’s ear as she draws our attention to her characters’ consuming passions. There is a great deal of dialogue in the book, all reflective of current London colloquialisms and these make the book accessible to those for whom a slim volume is ideal company on a journey to work, hour in the park, or welcome respite between other actions. In detailing this vibrant scene of self absorption so precisely, Liggers and Dreamers is more akin to having a fluid hologram in your pocket than it is to a piece of literature.

The characters breathe, shout and interact, showing both secretiveness and exuberance, with their frequent boisterousness exposing the relatively small regard even the practitioners of the London Art Scene hold their own context in. Contemporary Art, it seems to me, has never been concerned with its own process, or practice (see Damien Hirst’s Spot paintings or much, if not all of Jeff Koons’ output, both alluded to in the book) as it is with its own justification: ‘I earn therefore I am’ seems to be the prime validation and as Deborah, Simon, Ashpak, Tony Phun, Audrey and Irreverent George present themselves along with their various bête noires and fellows in the art of intrusion, they seem to regard themselves as part of the second wave of that success. A Private View becomes an internal process that a public show provides context for. As you formulate what you think of the work you must fuel the brain with as much champagne and canapes as your unworthy soul can accommodate.

Food, and more importantly drink, fuels these narratives, making the final river image pertinent, and indeed Josie’s Liggers float and bob on its unending surfaces, spotting and commenting on each other as they sail from glass to glass. When, near the end the Liggers notice that Bill Brown’s Albermarle Street Gallery is temporarily empty, they bemoan not the absence of art, but the absence of its commemoration, revealing their own desire to crown themselves Art’s designated celebrants. It strikes me that the contemporary art scene is concerned far more with how the work is regarded than with the work itself. Art has always been what the artists says it is, from the Neanderthal in the cave, through to Rembrandt’s mirroring of his own aging, via Duchamp and onto Sarah Lucas’ fried eggs, but Liggers and Dreamers true interest for me, lays in how its vignette based structure allows the protagonists to become their own Pictures at an Exhibition. Whether that exhibition is reflective of anyone else is not for me to say, but it certainly details life as it is lived in the privileged Cork Street ghetto.

A great many of us who live and who come from London and are perhaps residents of the suburbs like to know what’s on offer, even if we do not always avail ourselves of it. Meryl, Eustacia, Audrey and the rest of the posse are dependent on and indeed defined by those opportunities. Whereas Beckett once detailed his walks with his Father across fields close to Dublin with ‘their hands forgotten in each other’, these Liggers, Dreamers and Aspirsants log and detail every step of their will to accomplish pre-eminence. This idealised state or dream strikes me as being one of self preservation only, where lifestyle supercedes life and the choices we make are governed by promotion, propulsion and popularity.

Josie Demuth thereby proves herself as an adept storyteller, Chronicler and Journalist. The stance revealed in her book can be an obvious one in some contexts but it’s a statement made valid in this useful book, as we are warned that the modern world’s fascination with itself can ultimately take us nowhere than up and then back down the same river. The wind is behind us and yet our wings are not reached for and so we choose not to fly.

Liggers and Dreamers is a timely portrait of an attitude and an age. Thin Man Press have produced another beautifully made and printed paperback that feels and smells appealing to the senses. Once you have read the book, hold it up to your ear and you will continue to hear the voices within chattering away and glorying in their own escapades and endeavours. To expand the creative analogy further; Ms Demuth also paints her liggers clearly, with succinct and encompassing descriptions, from the observation that all Liggers are Lepers, to the Reverend/Irreverant George’s (Priest by day/Thief by night) observation that one of his fellow liggers tried to take communion four times, hunkering after the wafer in much the same way as they might for a private view’s tray of comestibles. This book is a tasty array of starters and implied courses. Once you have consumed it, I recommend a slow contemplative look at Velasquez as dessert.

David Erdos 13/9/15