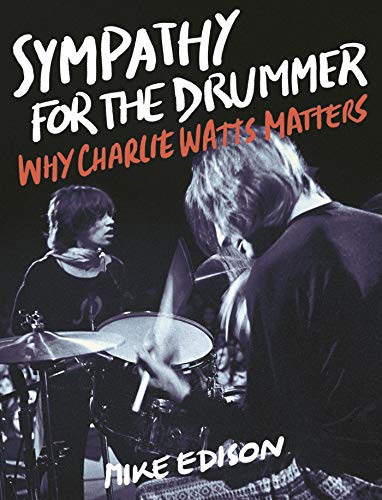

First off, this is one of the better books about the Stones – there are plenty of books out there, and plenty of them are tired retreads, but this one is different. So as well as Stanley Booth’s True Adventures, Keith’s Life, Bill’s Stone Alone, Andrew Loog Oldham’s Stoned and 2Stoned, the Tony Sanchez one, and Robert Greenfield’s Exile-era A Season in Hell, Mike Edison’s Sympathy for the Drummer: Why Charlie Watts Matters presents itself as essential reading if the Stones mean much of anything to you at all.

Indeed, for an insightful, passionate, knowledgeable, funny, fresh and astute take on the history of jazz, blues, country, R&B and the guys with the sticks and skins who built the rocket for the rock n roll explosion to come, Sympathy for the Drummer is hard to beat. It’s also an entertaining and insightful take on what makes the Stones the Stones – the wobble, the roll, the power of anticipation over penetration – and may just be the best Stones book on the music I’ve come across. And coming in the sixth decade of their career, when you might have thought it had been all said and done, to be given a brand new perspective-changing viewpoint through which to renew your appreciation of the Stones’ music, is a remarkable achievement.

Mike Edison is a drummer himself, and that helps. He was editor/publisher of both High Times and Screw, and that helps too. This is the Rolling Stones after all. His book begins with the key drummers who came before, through the jazz, blues and R&B worlds of the thirties through to the fifties – the likes of Chuck Berry’s drummer Ebby Hardy, Little Richard’s Charles Connor (the inspiration for the great 20th-century sound poetry of A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-wop-bam-boom), Chess Records house drummer Freddy Below, and Buddy Holly’s timekeeper, Jerry Allison. And the jazzmen – Gene Krupa, Philly Joe Jones, Roy Haynes, Tony Williamson, all of whom lit a spark and balanced the weights under Watts’ playing.

He sets our man against the big rock-era drummers – Keith Moon, Ginger Baker, John Bonham – drawing out the little touches and big differences that make Charlie stand out from the rest, and deftly takes apart a range of Stones’ classics (and some deep cuts too) from the POV of the drummer’s stool, with an acute eye on refreshing what is utterly familiar: Take this, on their last indisputably classic hit (from 1981): “The intro to Start Me Up is as famous a near-wreck as ever was on a hit record, completely fucked up upon take-off, and yet brilliantly resolved within the space of a few beats. College-level papers have been written explaining how Keith’s opening riff and Charlie’s miscued entrance fall together in awkward bliss.”

It’s fabulously eye-opening and does what music writing should do – send you back to the music directly, with fresh ears and an altered understanding of those songs’ dynamics. He even gives a rare thumb’s up to oft-dismissed mid-Seventies fare such as Black and Blue and Love You Live – encouraging readers to try playing along to the latter for a masterclass in Charlie Watts’ mastery of time.

He’s often funny, and astute – especially in the numerous footnotes, which also contain some of the best stories (the Starfucker trainwreck on the bootleg of Keef and the Stones’ concert for the blind back in 1977 being a case in point). “In a fundamental way, the blues is like pizza,” he opines at one point. “It has few ingredients, and yet it is astonishing how many people fuck it up.” Indeed. And he’s here to show how they didn’t fuck up when it came to working in that wobbly space between guitar, bass and drums, and teasing out a long string of fantastic songs that define both rock music and the Stones.

Edison takes a more or less chronological trip through Stones history, with plenty of asides and side tours – into Watt’s extra-curricular activities with the likes of Rocket 88, his Big Band and Quartet, and with several nods towards his sartorial elegances – though to be honest it’s a speedy run through the past thirty years (one chapter takes us from 1983’s Undercover to 2015’s Havana Moon) with the last hurrah of 2016’s surprise hit blues album, Blue and Lonesome (“perfectly timeless, and a welcome escape from the supercilious bullshit that tanked their previous half-dozen records or so”) bringing the book to a close. Here, Edison heaps praises on Watts’ use of the china cymbal (“simultaneously primitive and wildly progressive”) first employed on Some Girls 38 years before, and still going strong on Blue & Lonesome.

He’s good on why the Stones matter, too, and why their music and mythos won’t fade away – “it will come in and out of fashion,” he writes, “but it will never go out of style. The kind of rhythm and sexuality they trafficked in was never based on any trend – it was built from dirt and drugs and decadence and soul, it was Romantic in the grandest sense, and based in ancient knowledge, gained firsthand.” And, as he points out, we are not going to see their likes again; the environment that created the phenomenon of the Stones no longer exists and cannot be resuscitated or recreated. But it can be celebrated, and this is one celebration you don’t want to miss out on.

.

Tim Cumming