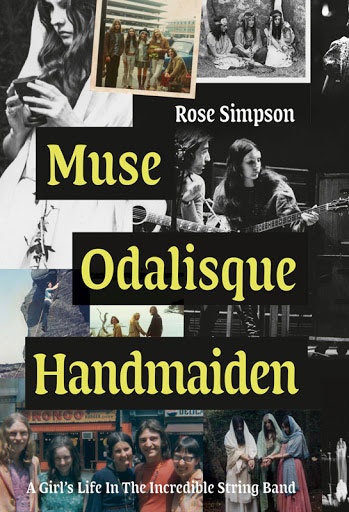

Rose Simpson: ‘Muse Odalisque Handmaiden – A Girl’s Life in the Incredible String Band’ – Strange Attractor Press paperback £15.99.

(http://strangeattractor.co.uk/shoppe/muse-odalisque-handmaiden/)

There was something of a ‘Marmite’ quality about the Incredible String Band. I fell for them when I first bought ‘The 5,000 Spirits or The Layers of the Onion’ album in ’67 or ’68, lured by the still magnificent Postuma & Koger (of ‘The Fool’) cover and the promise of music blending folk and psychedelia. My delight, however, was not shared by many of my teenage friends – despite our mutual love for Zappa, Cream, Byrds etc. etc. The curious intonations of Robin Williamson’s voice, along with his often rambling lyrics; the quirkiness and rough-shod feel of Mike Heron’s songs; the sound of the Gimbri and other exotic instruments – none of it sat well with the majority of those drawn to the nascent rock music of the times. Finding other people who loved the ISB felt special, you had something unique in common.

I was never in the right place at the right time to see the earlier incarnations of the band. When eventually I did see them in ’73 or ’74 they were already well on their journey through Scientology. Still enjoyable, but there was something uncharacteristically slick about them. Members of the audience were invited to stay and chat with the band after the gig, and I queued up to speak to Williamson. Asked about Scientology he extolled its virtues, even took my address and sent me a handwritten letter further extolling its virtues. It completed my sense of disillusionment, a man for whom I’d felt adulation had succumbed to a mind-bending cult. I lost interest, keeping only the first four albums for the memories.

Years pass and perspectives change. Williamson later found his way back into my heart, and there’s much that I still love about the early albums and even some of the later work. I remained curious about them as people, too. They’d been such an influence. The ‘Be Glad’ Compendium book published in 2003 answered some of my questions, and I was particularly intrigued by an interview with Rose Simpson, who graduated from being Mike Heron’s partner to full membership of the band from mid ’68 to the end of 1970. So when I got an email from Strange Attractor press announcing the forthcoming publication of a memoir concerning her time in the ISB, it was a must-read.

What I wasn’t necessarily expecting was to find such a clear. well-written, moving and balanced account of that time. I’ve read quite a few musician biographies and autobiographies over the years, enough to curb my desire to read more, but few of them reach the level of insight and, I think, honesty that I found here.

You might be wondering about the book’s title. I was. I had to look up ‘odalisque’ in the dictionary. It’s defined as ‘Eastern female slave or concubine’. The choice of those three words is, I suspect, in reference to how Rose and ‘Licorice’ McKechnie, the other female member of the band at that time, were seen by a good many ISB fans, particularly the male ones. The sub-title, ‘a girl’s life’ is knowingly chosen. In her preface to the book, Rose writes: ‘we seemed so wilfully to be ignoring the enlightenment of the more political feminists’, but later adds: ‘we too were claiming equalities, on the terms that mattered to us’. She writes too of her intentions in writing the book. ‘Over the years I have avoided reading, watching or listening to anything at all about the ISB, mostly because it hurt to be reminded of what was for me, in many ways, Paradise Lost.’ Nevertheless ‘my story is being narrated and sold, in the process of becoming a public commodity embedded in a monolithic history, I’m not content any more to let it be entirely out of my hands.’

Her approach to structuring the book is well thought out, ‘meshes of significance, overriding frameworks of time and place’, though a degree of chronological order and timelines at the start of each chapter remain for those who need it.

Rose’s first encounter with the ISB was coincidental. A York University student and a keen mountaineer she met them on an overnight stay in Temple Cottage, a kind of open-house refuge in Scotland for both climbers and folk singers – its features and ambience deftly described in the first chapter. She pictures Licorice as looking ‘folksy and very quaint’ and the two men as ‘even more outlandish, in curious clothes like drawings of medieval minstrels or wandering players’. Her attraction to Mike Heron in particular was, from this account, immediate: ‘…this face of wonder entranced me, all compact energy and a voice which spoke music veiled in smiles.’

She describes how the connection deepened and her relationship with Heron began, leading to a ‘peripatetic life’ of travel with the others. She observes closely how – despite the idyllic times in Temple Cottage – the band’s lives were already becoming structured by the demands of the music industry. Entrepreneur Joe Boyd figures largely in the story. It is he who advised Heron and Williamson to record and perform songs of their own, rather than the traditional material that figured in their initial partnership. His careful guidance did much to shape their early career.

Heron eventually bought a tiny ex-miner’s cottage near Edinburgh, and, when they were able to be there, he and Rose ‘played at home making’ in a time of ‘domestic bliss and country walks’. Looking back, she is balanced and non-judgemental in her portrayal of both her lover and of Williamson and McKechnie. Her respect for what they created in the early days is undiminished, but like all human beings they have their flaws, their vanities and their weaknesses. By way of an example she describes a night they spent drinking with comedian Billy Connolly. ‘Connolly’s admiration for Mike (was) clear. But Robin couldn’t resist the challenge of another teller of comic stories. This was his performance too. Verbal sparring continued, with no great good will on either side, apparently, until Robin turned away, looking arrogant and disdainful. This was his fail-safe expression when defeated and angry.’

Interestingly, when interviewed about his links with the ISB in 1997, Connolly’s praise for Williamson is generous, but there is still a hint of that rivalry in the way he chooses to express it: ‘he turned up good when he was fourteen, the kind of guy you want to just slap or disfigure: he’s handsome and he’s good, it was just bloody great. … God how I loved him.’

By the time of ISB’s fourth album, ‘Wee Tam and the Big Huge’, Licorice and Rose were making musical contributions to the band both in live performance and increasingly on record. In this respect, Rose acknowledges there was a gulf between themselves and the men: ‘we both knew that musical ability was not why we were on stage’. An attitude towards this from reviewers, fans, other musicians and celebrities was often apparent to them. Whilst the likes of Julie Felix or John Peel would welcome Williamson and Heron, the two women would be largely ignored. But both had clear and strong ideas about their role in the band. Rose is clear they were not ‘handmaidens’: ‘our mutual willingness to serve the divine manifestation of music flowing through Mike and Robin was tempered by the strong wills of two very real-life girls with a strong resistance to personal sacrifice.’ Amongst other musicians: ‘I tried to be honest… I was not a musician and made no pretence of being one. I loved playing what I was taught and delighted in acquiring new skills but this was the extent of my expertise.’

The book balances the delights of their role as fellow performers in such an idyllic venture as the ISB with the often gruelling tedium of touring, unaddressed frictions within the band and various misadventures. Woodstock doesn’t sound like it was much fun, nor does their attempt at communal living in the Pembrokeshire countryside, shared with Stone Monkey, a performing troupe of dubious ability favoured by Williamson,. Throughout the book, Rose is clear that she did not expect this to become ‘a permanent way of life’. For all their solidarity and shared ideals as a group, they remained individuals – keeping a certain distance from one another. In a section about her relationship with Licorice, Rose writes: ‘we avoided conversations that might lead to revelations’.

The seeds of the ISB’s decline were clearly sprouting even before, one by one, the other three members were sucked into Scientology. But for Rose: ‘I didn’t want to embrace a therapy aiming to turn me into an American provincial secretary or a happy housewife. … If this was the aspiration, I wasn’t interested.’ However, in a superficial sense, Scientology’s initial communication training did seem to have some beneficial aspects for the band, at least in terms of how they conducted their affairs and, open-minded, Rose went along with it despite her doubts. In time, however: ‘we trooped along like lambs to the slaughter, accepting each new course as a step in our progress towards Nirvana. We followed the same time-schedules we had once despised and abandoned, committing days and weeks to joyless classrooms, instant coffee and soggy sandwiches. We read reams of simplistic psychology and bad science fiction, telling us how the universe worked and how to improve our place within it.’ Eventually she found herself ‘seething with rage and frustration’. One casualty, she felt, was Robin and Mike’s songwriting: ‘They were now astray lyrically, the words lacking the conviction that had once given them vibrancy and power.’

After the commercial failure of another of Williamson’s ill-conceived projects, the stage play ‘U’, and a largely joyless US tour, the writing was well and truly on the wall. By then the band, still in the companionship of the Stone Monkey troupe, had set up a community back in Scotland, but in Glen Row each of the band had a separate house and the dreariness of Scientology was, for them, in the ascendant. As New Year 1971 approached, Rose, under pressure to match the others’ commitment, made her decision. ‘I walked out on all of it, on my home at the Glen, on my future with ISB and on my friendships of the moment.’ In a new relationship, pregnant and taking her first post-ISB job as an early-morning office cleaner, she began a new life.

In a thoughtful epilogue Rose returns to the joy of being part of the ISB for those few years, on-stage ‘carried beyond the worries and concerns of daily life to a purer state of being. … Then the show ended, and all the confusions of the material world took over once more.’ Finally she reminds us that ‘each of us… saw the same events through different eyes’ and that this is but her own viewpoint.

For anyone who, like me, loved the early ISB and have remained partial to at least some of Williamson and Heron’s work since those days, I recommend this book highly. For those on the other side of the Marmite divide, or anyone with perhaps no interest in the band at all but a curiosity about the hippie phenomenon as it was manifest in the late 60s, it remains an illuminating and engrossing read. It is both a celebration of the ISB’s achievements and a gentle warning regarding how the very best of intentions can go astray.

Richard Foreman