I ONCE ASKED Nelson Algren what he thought of Naked Lunch. He grinned at me, as though he were being entertained by a wiseguy. I knew he had no love for the Beats. He had derided Jack Kerouac as a Momma’s boy and dismissed Allen Ginsberg as a publicist. So his answer surprised me: “Burroughs wrote half of a good book.” He meant that as praise. What Algren liked were the horrific “routines” and their cosmic lineup of hilariously appalling characters.

When Mary McCarthy came to the book’s defense in a widely publicized obscenity trial, she pointed out that Burroughs was nothing if not a moralist holding up a mirror to a nasty world. Norman Mailer said on the witness stand that “Burroughs may be the only contemporary American writer truly possessed of genius.” The remark, more widely quoted than any other, helped turn the book into a scandalous success — and Naked Lunch, which established Burroughs’ reputation as a writer of the blackest satire (“since Jonathan Swift” in Kerouac’s estimation), took its place as one of the three crown jewels of the Beat Generation, alongside Howl and On the Road.

But being a serious writer hardly meant leading the life of a saint. In 1951, in Mexico City, long before the publication of Naked Lunch, Burroughs accidentally shot and killed his common-law wife Joan Vollmer in a drunken stunt to prove his marksmanship William Tell-style. Instead of hitting the glass placed on her head, he shot her square between the eyes. Jailed for two weeks, he was freed on bail (the result of a bribe), and eventually sentenced to two years in prison for negligent homicide. By then he had fled the country. But he was devastated by Joan’s death, contrary to his reputation as a woman-hating homosexual.

Burroughs spent many years in Paris and Tangier, where his narcotics addiction flourished and took its revenge until he left for an apomorphine cure in London. Some years later, he arrived in New York, where he set up shop in an austere loft on the Bowery known to his friends as “the Bunker.” There he became a reclusive celebrity, hailed as a culture hero by the New York underground. It wasn’t long before he left for Boulder, Colorado, where his son, William Jr., also a writer and drug addict, had gone for a liver transplant.

I spoke with Burroughs by telephone when The Place of Dead Roads, his fifteenth book, had just been published. I was in Chicago. He was in Lawrence, Kansas, having decided to take up permanent residence there. Burroughs seemed cheerful, although his speech sounded as clipped as ever. The congenial mood of the conversation was helped perhaps by our bit of history together. I had published some key cut-up texts of his in a literary magazine during the 1960s and had made an experimental video with him in London in 1970. He declined to answer only one question — when I asked him to describe the events surrounding Joan’s death.

“I discuss all that in the film,” he explained. He was referring to “Burroughs,” a feature-length documentary by Howard Brookner that hadn’t been released yet. “I said it once, and I’ll say it once only. Since I did it there, I don’t go over it again.”

Burroughs had suffered from a severe case of writer’s block while working on the book just before Dead Roads — Cities of the Red Night — which seemed odd to me. Ken Kesey and others had called Cities his best book. When I asked what had caused the problem, Burroughs was surprised by the question but took it in stride.

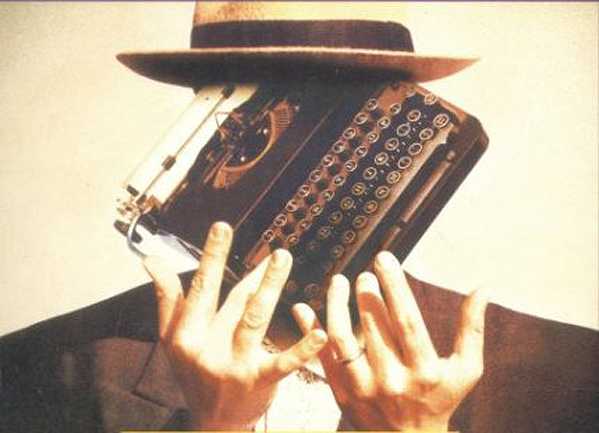

“Good heavens,” he said. “No one knows why writer’s block occurs. It can occur from one day to the next. Suddenly you can’t stand to look at the typewriter. For every writer who stays in business long enough, it’s an occupational hazard and you’re going to run into it sooner or later. There are many causes. One of them is overwriting.

“Mary McCarthy said about me, ‘Well, he writes too much.’ That’s quite true. It’s like the general getting ahead of his army. His supply lines are cut. Nothing comes through. You drain the reservoir, as Hemingway might have said. It isn’t good to drain the reservoir. You should always give it time to fill up. However, there are many other causes. It’s hard to say. I’ve known people who have written one or two books and then they get writer’s block and never write again.”

It occurred to me that the difference between Dead Roads and Cities may have been a factor in getting past the block. Dead Roads was less confounding than Cities because so much of its leading character seemed an amalgam of Burroughs’s autobiographical memories. He readily agreed.

“The Place of Dead Roads is simpler and more accessible and much more centered around one protagonist,” he said. “It’s absolutely in the oldest tradition of the novel. The unfortunate traveler encounters a number of adventures — sometimes comic, sometimes mythic. It’s very easy to say what the book is about. It’s about survival. It is also concerned with man’s attempt to rewrite or rework his own destiny.”

In Dead Roads, Burroughs had written, “Language sense is like card sense. Some people have it. Some don’t.” Clearly, Burroughs had it. Joan Didion once remarked of him that he was “less a writer than a sound.” But that was going too far. Anybody who reads Junky, his first book, or any number of passages from his others, knows that he easily composed straightforward narrative prose. It still formed the bedrock of the hallucinatory style he had cultivated ever since Naked Lunch.

Burroughs had changed from the days when he and Brion Gysin produced their “cut up” manifesto, which abandoned “the fetish of originality” and declared that “nobody owns words,” that “everything belongs to the inspired and dedicated thief.” Why then, more than two decades later, did he continue to insist on using the “cut up” method to collage his own and others’ words with results guaranteed to limit his readership? Why didn’t he dispense with nonlinear plots and composite characters, and simply bow to literary convention by propping up his “novels” with easy-to-read beginnings, middles, and ends?

I knew the answer of course. He had noted time and again that art should have the power of dreams. Where else but in dreams can time and space be run backward and forward like film stock? Where else do the obscene and the erotic have permission to merge? Where else is “ordinary reality” repudiated so easily? And if dreams have the power to dissolve the rational disguises of civilization beneath the corrosive acid of the unconscious, why should art possess anything less? The “cut up” method carried to its logical conclusion as a theory of composition accessed the power of dreams.

And so in Dead Roads he refused to retreat from his surrealistic vision, his obsessive homosexuality, and his savagely cold-blooded humor. The story begins and ends on Sept. 17, 1899, with a shootout in Boulder, Colorado, between a gunfighter, Mike Chase, and a real estate speculator, William Seward Hall, who writes novels under the pen name Kim Carsons. Burroughs shared Hall’s Christian names, of course, and he, too, once took a pen name. The gunfighter’s name echoes that of Hal Chase, a handsome, hetero Columbia grad student from Denver who had roomed with Joan Vollmer, introduced the Beats to Neal Cassady, and later, among the American expats in Mexico City, was hostile to Burroughs. Meanwhile, the real Kim Carsons (read: Burroughs in his youth) rides through the waning days of the Old West when gun fighting was a profession for misfit “shootists.”

Since his books were filled with gun lore, I asked what had spurred his interest in guns in the first place. “That was just the way I was brought up,” he said. “In the 1920s America was a gun culture. Everyone got a certain gun. You got your air gun and your sling-shot .22 and so on. I was brought up with guns. When I was living in Europe and in New York, I put that aside. And when I came back to small-town living like this, I was able to take up that hobby again, as well as the whole consideration of weaponry in the widest sense from guns to biological mutations to religion. It’s all weapons.”

Two other preoccupations of his were, increasingly, biological mutation and space travel. I asked why. “Well,” he said, pausing for a moment as though to let me know the answer was obvious. “I think that’s the only place the species can go. Man is an artifact for space travel in a state of arrested evolution.”

I wondered whether his outlook had changed over time. “No, my opinions on that haven’t changed in 50 years,” he said. Did he care to elaborate?

“Well, of course, I believe in reincarnation, which is a very bad idea at the present time. The point is that you don’t move of your own volition any more than a chair does, being very much the same substance. In other words, what moves, what animates the human body is an electromagnetic field. Now an electromagnetic field can theoretically be moved, given the knowledge, from one situation to another. It could conceivably exist without a physical body. It exists in a computer. There are many possibilities. You aren’t your body any more than a pilot is the plane, although the pilot has to observe certain rules or he’s going to be in very bad trouble. He can’t step out of his plane at 35,000 feet. There are all sorts of things he can’t do if he’s going to survive.”

Burroughs had often said he was writing for the space age. I asked whether he had any faith in space programs. He had probably been asked that a thousand times, but he didn’t seem to mind

“The space programs have demonstrated a very useful thing. Of course, they’ve simply sent these people up in an aqualung. It’s like taking some fish in an aquarium and bringing them up on the land. But they still have made a very useful demonstration that man can actually leave the earth. It’s one of the few public expenses that I don’t begrudge. But it’s only a first step. My feeling is that the transition from time into space is going to be quite as drastic as the transition from water to land.”

When I asked why he had called Christianity a “dangerous illusion,” he warmed to the question. “The point,” he said, “is that the one-god universe is a dead-end horror. All right, He’s all-powerful and all-seeing. It means that He can do everything and He can do nothing. Doing implies opposition. He can’t change because change implies introspection and action in opposition to something. In other words, this is the classic thermodynamic universe. It’s bound to run down by definition. That’s what I’m talking about. The magical universe, which is unpredictable and spontaneous, is a living universe. The one-god universe is dead. And that goes for any one-god religion. Islam is just the same.”

Besides all the gun lore, Dead Roads contained lots of mummy lore, another Burroughs specialty and one of his fondest cosmic jokes. Burroughs writes, “Kim considers that immortality is the only goal worth striving for. The most arbitrary, precarious and bureaucratic immortality blueprint was drafted by the ancient Egyptians. First you had to be yourself mummified and that was very expensive, making immortality a monopoly of the truly rich. Then your continued immortality in the Western Lands was entirely dependent on the continued existence of your mummy. . . . Anybody buy in on a deal like that should have his mummy examined.”

Carsons gets around “the mummy route” the way the 11th century Arabic assassin chief Hassan i Sabbah got around it in his mountain hideout of Alamut: sex between males. “It is possible to resolve the dualistic conflict [body and spirit] in a sex act, where dualism need not exist.”

As far as Burroughs was concerned, heterosexuality — a dualism by definition — did not apply. Carsons, being homosexual, finds his soul mates in the Johnson Family, an outlaw gang of clones not unlike Hassan i Sabbah’s assassins, which hides out near St. Louis (where Burroughs was born).

Neither Carsons nor Hall nor any of the Johnsons ever find immortality except on the printed page. And that, finally, includes Burroughs himself. “The immortality of the writer is to be taken literally,” he explained. “Whenever anyone reads his words, the writer is there. He lives in his readers.”

I asked which of his books he considered the best. “I withhold judgment,” he said. “Writers are poor judges of their own work. They always tend to think that the book they’ve just written that minute is the one. In some cases it’s glaringly untrue. James Jones didn’t realize that From Here to Eternity was his only book.”

“What about Jack Kerouac?”

“Well, On the Road because it’s such a classic and said so much to so many people in America and Europe and elsewhere that it did tend to eclipse his other work. I had the impression that in the last two or three years of his life he was hardly writing at all. Whether he knew it or not, he was dying. I don’t know if any doctor held a gun to his head and told him, ‘If you don’t stop drinking, you’re dead.’ If that had been done, say, five years before he was dead, it might have saved him. Because you can get along with, oh, I think ten percent of liver function. But you can’t get along with none.”

Burroughs had often been called a “scion of the Burroughs adding machine fortune.” I wanted to know whether that was true and, if so, what his personal relationship to it was. “Oh, it’s pretty simple,” he said.

“My grandfather, the inventor, died at the age of 41 in Alabama of tuberculosis. That would be about 1897. My father, I think, was 12 years old. So the children were quite young. There were four children: Aunt Jennie, Aunt Helen, and Horace, and my father Mortimer. What apparently happened was that the board of directors persuaded them that the whole idea of the adding machine was impractical and they’d be better to take any offer they can get. Obviously it looks from here like a plot on the part of the executors and the investors to buy the family out. The children received $100,000 each. That $400,000 in stock would now be worth about $50 million. My father started a glass company with his $100,000 and he ran that quite successfully for a number of years.”

This raised another question: Had he been living off a secret trust fund when he first met Ginsberg and Kerouac?

“No. All that stuff about a trust fund is absolute rubbish. That was all concocted by Jack.”

Well, not entirely. Burroughs may not have had a trust fund, but he had a small monthly allowance from his parents. He finally gave it up when his writing provided enough income to live on. By then he was into 50s, or nearly.

When Queer appeared, in 1985, the year after our conversation, it was revealed as the missing link between Naked Lunch and Junky, a thinly disguised fictional account of his life as a drug addict. According to rumor, Queer had been withheld because it contained homosexual content too shocking to publish. But it turned out to be both more and less than anticipated. More, because the coruscating wit of the “routines” was already present in virulent form. Less, because it was much less explicit than books like Dead Roads and Cities of the Red Night.

When he wrote Queer, in 1952, Burroughs was living in Mexico City like a desert traveler at the last oasis. He had recently skipped bail on charges of heroin and marijuana possession in New Orleans and was waiting for the statute of limitations on the charges to run out. The most fascinating aspect of this fragmentary autobiographical novel was that the young Burroughs (portrayed by his alter ego Bill Lee as part of a tough, aimless clique of American expats hanging around Mexico City during the late 1940s) is shown to be a deeply wounded figure whose need for human tenderness seems almost to devour him.

.....Furthermore, in a lengthy introduction to Queer that puts its publication in context, Burroughs wrote one of the most absorbing pieces of self-analysis he ever produced. It may well rank with the most perceptive critiques any author has written about himself. ......Explaining “the heavy reluctance” that paralyzed him when he started to write the introduction, he noted that he almost couldn’t bring himself to read the manuscript of the novel at first. “My past was a poisoned river from which one was fortunate to escape,” he points out.

......As he forced himself to read what he’d written, he discovered that the entire story was “motivated and formed by an event which is never mentioned, in fact is carefully avoided.” The death of Joan. Thus “the heavy depression and a feeling of doom” that dogs Lee throughout Queer is not attributable to his failure to succeed with Allerton, a drifter who infatuates him and with whom he travels to South American in search of the hallucinogenic drug called yage, as Lee believes, nor even to the acute junk withdrawal he is experiencing. It is attributable, Burroughs now believed, to what he came to see as a mediumistic possession. He had been warned of it in precognitive dreams and in many of his experimental writings.

…..“I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer, but for Joan’s death,” he writes, “and to a realization of the extent to which this event has motivated and formulated my writing. I live with the constant threat of possession, and a constant need to escape from possession, from Control. So the death of Joan brought me into contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a lifelong struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.”

It is highly instructive to know this. Certainly it explains the subtext of one peculiar incident in Queer in which Lee, high on rum, Benzedrine, and pot, fires his revolver at a mouse held at arm’s length by a busboy in the Ship Ahoy, a down-at-heels hangout that provides a captive audience for Lee’s increasingly manic performances. (“‘Hold the son of a bitch out and I’ll blast it,’ Lee said, striking a Napoleonic pose.”) And so the story, as Burroughs himself noted, “takes on a hellish glow of menace and evil drifting out of neon-lit cocktail bars, the ugly violence, the .45 always just under the surface.”

......Still, the narrative style and mood of the prose is almost serene in its lucidity, as though it were a phenomenological exercise describing only what meets the eye or ear. Queer reads so swiftly it can be finished at a sitting — further evidence that Burroughs wrote with a beautiful, rarely matched efficiency. His lifelong struggle with the Ugly Spirit turned out to be more than an escape from Control. It was the wormhole to an afterlife, no mummy needed.

Jan Herman

Due to be published by Cold Turkey Press in 2015

###

Wow Jan – what a wonderful writer you are. Takes me back to Guy Place and hearing you and Gail talk with such irreverence about subjects slightly beyond my experience . Didn’t the two of you edit or publish a book by boroughs in your SF Earthquake?

Comment by Susan Sherrell on 19 December, 2014 at 6:40 pmGlad you enjoyed it, Susan. Gail and I started the magazine together. The Buroughs book that you are probably referring to was actually a foldout pamphlet in covers, titled THE DEAD STAR. It was the fifth in a series of six Nova Broadcast Press pamphlets that I edited and published separately from the magazine. THE DEAD STAR was originally published in the U.K. in Jeff Nuttall’s mimeograph version (via his gritty avant-garde publication My Own Mag).

Comment by Jan Herman on 20 December, 2014 at 6:26 pm