Butterfly of Dinard, Eugenio Montale (New York Review of Books, 2024, £15.99, 209pp.)

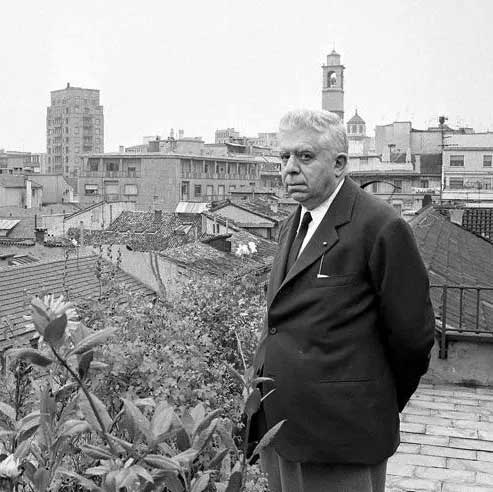

Nobel Prize-winning poet Montale is mostly known for his Dante-influenced, challenging poetry, a major part of the modern Italian literary landscape. These fifty short prose pieces act as an interesting byway amidst this greater poetic achievement. Produced for the Italian newspaper Correre della Sera, they were written from 1946 until the early 1960s, but many of the earlier stories are set further back, in pre-WWII Liguria, with autobiographical, but lightly disguised situations and glimpses. Jonathan Galassi goes to great lengths in his introduction to see them as mongrel mixtures of essay and sketch, but there is a deftness and lightness of touch that enables them to float free of such generic restrictions – they are more like brief observations from a flaneur at the bar, buttonholing you and giving insights into the social layers and political constrictions in Italian society just before and after the Second World War. Imagine Yeats writing brief society pieces for the old New Yorker and you’ll be in the right ball-park.

There’s nothing heavily bogged down or freighted by symbolism or narrative strategies here – the narrator is a version of Montale himself and each brief piece passes like a shrug at the end of a conversation in a neighbourhood café in a Milan backstreet. The early Ligurian sketches like ‘The Regatta’ and ‘Laguzzi & Co.’ describe teeming apartment life and class rivalries with joy and pungency. Unsurprisingly, food and social climbing are both important. Later pieces, written under the shadow of Fascism, are darker, threaded with dangerous possibilities – Montale was a lifelong anti-Fascist – but the vivid street life of the Italian working-classes continues, as colourful and picaresque as before.

The third section of sketches, mostly featuring a narrator challenged by a female voice, modelled on Montale’s wife, Drusilla Tanzi, are a little more formulaic, but even here, pieces like ‘The Director’, cheerily exploring a supernatural encounter, are full of charm and Borgesian wit. Another standout piece is ‘Poetry Does Not Exist’, ostensibly a risky wartime meeting between an intellectual and a Fascist translator of Hölderlin, which mischievously suggests judgements and compromise: ‘Believe me, poetry does not exist. When it’s old, we can’t identify with it, when it’s new, it repulses us the way all new things do, having no history, no character, no style.’

The final section features several much later stories, many extremely brief, almost imagist in style, in which the narrator becomes more of a foolish observer of life: Galassi describes him well as a ‘Chaplinesque antihero’, but like all such picaros he is more sophisticated than he seems. The subject-matter often touches upon mortality and hints at the way life’s aspirations are unfulfilled, bereft of meaning or unsatisfying. Nevertheless, Montale is able to infuse a journey into the shades, in ‘At the Border’, with affecting positive touches, and more sentiment is evident in the memories of past friendships and acquaintances explored in ‘On the Beach’ and ‘The English Gentleman’.

Taken as a whole, this collection is an act of bricolage, a mosaic illuminating Montale’s wry and fluent, conversational tone. He himself regarded their subject-matter as trivial and yet full of meaning at the same time, recording the comical aspirations, the pretentious sophistry and the fading aristocracy observed as daily life went on in Liguria and Florence. Seeking to explain their hybrid ancestry, Galassi finds stylistic resemblances to the society novelist Ivy Compton-Burnett, but for me they recall, at times, the wit of the British essayists of the early twentieth-century – Robert Lynd, E.V.Lucas, J.B.Priestley, even the paradoxes of Chesterton, so beloved of Borges. At other times, they indulge in light gestures of cosmic irony not dissimilar to Italo Calvino. Despite these echoes, Montale’s voice is individual and winningly mocking, even when dealing with matters of great importance. Those coming to them looking for light shed on his apocalyptic poetry may have to look elsewhere, but for others these brief, but never insubstantial sketches are a pleasure to read. Though ostensibly weightless and slight, they gradually build into a real achievement, illuminating the brief vanities of the glittering Italian society of the time and those who cunningly observed it without being entirely a part of it.

M. C Caseley

.