(An introductory note on the Russian poet Galina Rymbu)

It would be natural to compare Arthur Rimbaud and Galina Rymbu

even if the Russian had another surname. She is strikingly youthful

and politically engaged. But the sonic coincidence is rather special.

Ignoring it, she might equally be worth comparing to other ferocious

forces of lyricism such as Pier Paolo Pasolini or Katerina Gogou. It’s

a leftist poetry we’re talkimg about, one that might be repellant to

those of other creeds. But a poetry simultaneously this strange and

this sociopolitical is unusual. You read it and re-read it, punched in

the face by its righteous weirdness. You ignore the nosebleed.

Perhaps this stanza is Rimbaudian:

o, who could

guess these

are caravans of slaves coming to meet us?

But that would only be due to the keywords ‘caravans’ and ‘slaves’.

Perhaps this stanza is Rimbaudian in attitude:

the dead cock that protrudes from every philosophy

Alain Badiou fucking theories, numbers,

a weeping member, the cock of greasy philosophy

what are you good for, if you could only save us

What an hilarious piss-take of the Western philosophical tradition.

The scatology and subversion is certainly like Rimbaud. But add to

that: Russianness, femininity and a way of looking at the proletarian

mindscape and landscape through a highly estranged and estranging

lens, and you are looking at a poetry of charged significance, for its

own Russian readership and for the English readership who examine

the excellent translations made by Joan Brooks.

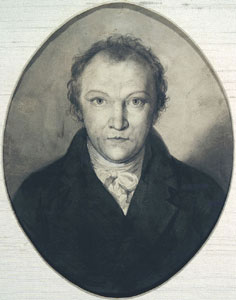

The scatology of certain canonical poets such as Blake, as well as

Baudelaire and Rimbaud, is in most cases to be found in notebooks.

In most cases it was not part of the official oeuvre e.g. ‘Scatological

Sonnets’ by Rimbaud and Verlaine, Baudelaire’s satirical doggerel

about Belgium, Blake’s ‘If Blake could do this when he rose up from

shite/What might he not do if he sat down to write’. But that was all

pre-Ubu, pre-Ulysses. Modern scatologists can scatologise freely, on

paper at least. Rymbu’s scatology is everpresent, a natural part of her

utterance. One of my own rules of poetry is: There is no such thing

as bad language, only bad usage’. Rymbu’s good usage confirms the

adage. The translator has done well to render the scatology with a

minimum of fuss.

Bashlachev

Young, rotten-toothed Russia hovers with her dry cunt over the

jailhouse shitter in thought—

A critical note has associated her with the neo-punk artistic milieu of

Pussy Riot. Rymbu mentions ‘chansonnieres’. I tentatively imagine

she might be influenced by the great ‘rotten-toothed’ songwriter

Alexander Baschlachev (1960-1988) who is taken very seriously as a

modern Russian poet. They diagnose with imagery:

Bashlachev:

Today doesn’t change anything.

We’re balding real quickly.

And drinking real slowly.

Today on the street it stinks horribly,

Reeks from somewhere, something is rotting.

We’ll take off our pants, but remain in our hats,

Turn off the lights, but put out the fire.

On the street there’s a toxic atmosphere.

Tell me where is this stench coming from?

Somewhere a giant egg is rotting

Rymbu:

Dim corpses,

wrapped in St. George ribbons, sweet mummies in empty bars and

restaurants

having a nice talk—about the possibilities of independent art and

new forms,

about the posthuman world, about cheese and wine, which melt

our hearts, the hearts of the “backward.” While the virus of outskirts,

the virus of borders

is already destroying their common sense, dear reason. Here’s a

question—

Both poets share a tone of disgusted utopianism.

Bashlachev:

But the white snow is stained with blood

And the wind is at my back

To each sister – a love…

Only be with me

Only live

But the throne is never vacant:

To each brother – a cross of guilt

Only, only don’t ask for help,

Accept and carry through.

Rymbu:

Lesbia, rise! the time has come to sing a joyous song,

spitting blood and the tooth fairy,

covering our faces with our hands, ripping up the asphalt,

until our brothers, our friends, our parents

stand in a circle and shout: “opa! opa!”

Grotesquerie abounds also, reminiscent of surrealism but much more

realistic. In ‘Winter Diary’ there are various horns, and more:

a coded sound – a French horn, in comes an orchestra of autists

in magic carriages to the cackling of iron actors and the chatter of the

auction

a sale on scorched backwater ontology in the slime of pudenda

I am only dreaming this, only dreaming

The point of the scatology and grotesquerie is: it’s a sacred function,

it’s Joycean. The human body is present in this poetry in all its

actions. As anything can happen to human bodies, so anything can

happen in this poetry; it can give birth, it can become diseased. This

is not a religiously anti-religious poetry like Rimbaud’s, but perhaps

offers something of Joyce’s transcendentalism. There is urgency, in

squalid conditions, to transcend. The tone is less comedic, less

celebratory, but it is not lacking in comedy or celebration.

sitting turkish-style (or indian-style, as you lot say) online

you broadcast something from the loudspeaker of opposition,

like a lackey, with restless glances into worn lacunas, …

here a steel voice gnaws through the frame of leviathan, that drunk

crocodile…

The poetry is a critique of Russian society, Russian life. Mention of

Leviathan – ‘thst drunk crocodile’ – puts me in mind of the amazing

Russian film Leviathan by Andrey Zvyagintsev. Both poet and

filmmaker are presenting tragic Russian infrastructures, social

wreckage. Rymbu, like Rimbaud, is more art-activist though and is

unabashedly flying a revolutionary banner, as the title of her first

book attests: Moving Space of the Revolution. In their Russias we see our

own nations reflected. State gangsterism et al. But leftism is relative.

When a Russian poet uses the word revolution, s/he cannot help but

look back with a sigh. It’s similar but different to an English leftist

looking back to Cromwell and his Roundheads and Puritans. Rymbu

says in prose:

Leftist, engaged political poetry must practice its own reevaluation of

the revolutionary past and the socialist experiment in order to find a

way to produce a genuinely alternative revolutionary culture, one that

corresponds to the class identity of the future revolutionary subject,

liberating the majority’s political vision, its sensuous perception of

things.

The poem ‘In My Head’ is a perfect and perfectly titled revolutionary

poem. Social dysfunction is rife, but the poet’s head is like a Siberian

shaman’s. (She is Siberian).

Now this iron accordion blows its bellows from our innards,

Its music hits you all the way to your bones,

leaving no room or time for tears. We are drawn inside this music,

twisted up in racing sleep.

Fast learner, war is coming up

to the walls of frozen buildings – who’s that in there with you?

Nobody. When we were kids they’d hide us in the factory pipes,

in copper cables, under the desks in school, so we’d be quiet.

In my head the Irtysh River is roaring and stretching long,

the fiery banks are crashing down,

the Taiga is beating a bearskin drum, and the beast tears a red flag

with its teeth.

Russian oil is sarcastically celebrated via an imaginary three-in-a-bed

session with oligarchal capitalism:

Time opens the doors of minibuses, the gates of the earth,

to release the burning miners,

the sharp stones, the lusty oil.

There’s a little oilman now in every bed instead of lubricant,

Dropping his black mouth on my pillow,

Scuttling between cunt and cock,

We think we’re loving one another, but it’s him spurring on our

passion.

Consciousness of time and history culminates in a good oldfashioned

agitprop slogan:

In a fur hat slipping down over his eyes and a bulletproof vest

With his cock sticking out, ripping forth like an arrow into a better

life

In the dark of the construction site flies my angel of history, my dear

comrade. His voice unprinted glows in this letter.

And so my hand under his sign in night matter

unconsciously comes to its own conclusion:

IMPERIALISM WILL BE DESTROYED ALL THE SAME!

THE REVOLUTION IS COMING.

Nothing wrong with agitprop for anyone of intelligence. On the day

it was announced Bob Dylan had won the Nobel Prize for Literature,

Dario Fo died, both masters of agitprop, among their many gifts. In

the slogan above with its banner-like upper-casing, the “ALL THE

SAME!” strikes a Rimbaudian tone between irony and sincerity.

Derek Mahon tells a story of how he was asked if he knew what

young poets in America are writing about today. ‘Love and

revolution?’ he asked back ‘No. Food…’ Rymbu writes about love

and revolution; but her English chapbook is called White Bread. A

poem of that title appears in White Review 17 and is a nightmarish

satire on the subject of the humble factory-produced loaf. It makes

me think of the “satanic mills” of Blake’s Jerusalem and the Albion

Mills bakery it was historically based on, burned down by arsonists in

1791. Before industrial capitalism, everyone ate artisan bread. The

stuff in Rymbu’s poem is satanic manna, vandalizing the metabolisms

of the poor. Everywhere, we are poisoned by industrially imposed

diets.

Apologies for this guesswork assessment. For the new Anglophone

reader of Rymbu, there is not very much to go on. Her work has

appeared in a few magazines. There is a short appreciation in English

by another Russian writer, Eugene Ostashevsky, and a short

interview with her translator. She thinks in terms of ‘underground’,

which is something I’ve been hearing a lot less about in London but

which used to be an important idea for me. It’s good to hear it again.

In Russia, ‘underground’ was the culture of Bashlachev, a rock poet

in an era when rock music was banned as the epitome of western

decadence. But underground culture, underground solidarity is not

enough for Rymbu. More collectivity and organization is needed to

foment an institutional solidarity, one whose message can infiltrate

the public sphere and take on what Althusser calls ‘ideological state

apparatuses’. A false capitalist culture – like the white bread – is

industrially imposed; a marginal culture opposes it; but the truth is

that the margin is the mainstream, the real culture. It’s also good to

contemplate her idea that artists need to be activists, even if activists

don’t need to be artists. And I am in total agreement with her idea of

love as ‘principled powerlessness’.

The poems are Guernicas, huge canvases of war. Militarism and

sexual violence are omnipresent backdrops. One untitled poem

opens with a chorus of different male voices claiming that what is

happening does not technically qualify as ‘war’:

“This isn’t war,” said a guy with a half-shaved head in the metro

to another guy, who was shaved all the way.

“No, not war,” say the analysts, “just some kind of action.”

“The territory of the occurrence isn’t completely clear,” comrades

affirm in the dark.

“War is different,” you said, embracing me. “You don’t have to

worry,” the government officials say with confidence on the live feed

on all the remaining channels, but the blood is already breaking out,

quietly, on their foreheads, near their auditory canals—thin streams,

until a fountain pours forth from their mouths.

The visionary juxtapositions continue with a beautifully ironic appeal

to ‘dear reason’:

How many sides are there in this war?

No more no less, no more no less. A jetliner with a glass bottom

crosses the borders of several countries. The leaders inside, bloated

with fat and fear

look down, over black clouds—hatred and wrath—

finishing their final cruise. These demands raised against us

fall, humming, into a dark empty gullet.

The enthralling bleakness of the poem – like something from a

prophetic book by Blake but updated to include airplanes etc. –

nonetheless offers a sanctuary at its close. Here is another connection

with Rimbaud. A highly sophisticated youthful consciousness

questions the raison d’etre of the military industrial nation states. If

the poem is titled by its opening phrase, then this poem is perhaps

called ‘This isn’t war’, a fine title for a fine poem.

Eugene Ostashevsky praises the poem ‘the dream is over, Lesbia’ ,

which was posted on the day that Russian troops began operating in

the Crimea, an instantaneous retort to the latest historic installment,

and to the jingoistic fervor of the accompanying news reports. It’s

another strange and astonishing work. It contains Russian references

and plays on language games and Putinisms that a Western reader

won’t immediately register, but the whole poem expresses a message

that nourishes and inspires. The all-important Lesbia evokes classical

western literature, Catullus, and finally Sappho and would seem to be

a feminist poem in which the poet addresses a community of women

who are living through more mass-orchestrated male violence. Its

crescendo achieves a modern catharsis, as well as a gob-in-the-face

redress. It reminds me of Tom Leonard’s cri de coeur about hating

“male fucking violence”.

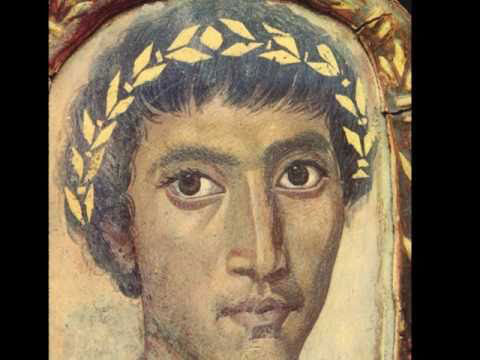

(The irreverent penises that appear throughout the poems may be

inspired by Catullan scatology, such as the final line from his

penultimate poem 115 where he describes the prosperous Mentula as

“not a man, but, in truth, a great projecting Cock.”)

The pathos of the poems is what I call ’the pathos of dissent’. Poems

that apolitical readers might dismiss as too indignant, too polemicized

to count as proper poetry, are moving to fellow dissenters who

understand the world that necessitates such expressions, and

empathise with those who risk the marginalizations and

misunderstandings of engagement, an awake minority in a not-soawake

society:

the sleepers wake inside the dream, the awakened

doze on iron fainting couches, in the burrows of moles.

the politics of absence plays cards with itself.

inside every sign is a hallway, straight, down which

you walk alone.

As a dissenting poet, Rymbu is comparable with the poet of

Exarchia, the Greek anarchist Katerina Gogou (1940-1993). Perhaps

the main difference is that Gogou is more hardline, reflecting a more

extreme mode of resistance, one that espouses violence e.g. “The

first man and the last I ever loved was an urban guerrilla”.

I prefer Rymbu who fights fire of the language of violence with fire

of her own violent language. She seems more translatable. Their

English reads like original poems, and one suspects they would do

their work in and through any language that did not censor or

sabotage them. The poems are so accomplished that they could and

should exert their pathos of dissent on all who peruse. They rise out

of a minority culture but one that is protesting against the actions a

nation-state is performing in its name – and in the name of history

and politics – and concern whole populations. Though the writings

limn the situation in Russia, they are as applicable to western neo-

colonial warmongering nations.

Catullus

Catullus

Rimbaud is not referenced. So far, the only allusions to western

writing I find in her poems and comments, apart from pauvre

Badiou, are to a broad gamut of Italians… Catullus, Dante, Pasolini:

I’ll write you: today,

arriving in moscow from siberia,

and finding ourselves in the center of town, in the Lovers of Fortune

supermarket,

looking at the people, in ironed t-shirts on top of everything,

and I feel – no, not “class hatred”,

some kind of unhealthy awe, as if I’m five years old,

some kind of dull, passive disgust,

also because I am there among them (without generalizing, but

looking

directly at each one, examining them more intensely),

Fortuna! I want to be more rageful even than Pasolini in his poems,

but the state of poetic form today and overall

the state of any kind of resistance today, in which

it’s impossible to allow that kind of rage –

it’s invisible, unproductive.

This is a complex and subtle as well as original poetry. To the

question of whether it is too difficult for the subjugated classes she is

channeling and voicing, her response is in-depth:

It can seem like the oppressed have a simple language, that we should

employ a series of reductions to work with this language in order to

be comprehensible as poets and artists. But there is no such thing as

a simple language, just as there are no simple emotions. Here

everything is even more complex—a real rat’s nest of complexity

made up of the languages of violence, ideological pressures,

propaganda, biopolitical manipulations, survivals of the past,

fantasies, hopes, and even certain seeds of “emancipation”—

meaning, partially violent concepts that provide an intuition of what

might lead the “simple people” to freedom. In this sense, the idea of

“simple language” is really just a total syntactic, lexical, and discursive

collapse, and it’s very hard to work with it, almost impossible. At the

same time, the discursive subject here is split just like everyone else:

he experiences a constant conflict between the productive relations in

which he participates (including the production of language) and the

systems that sell back to him the fruits of his own labor. He sees that

the world in which these products are bought and sold is not the

world in which he produces them. They are two different worlds, two

languages, both of which subjugate him. Today he knows this even

better than workers did in the beginning of the twentieth century, but

the collapse of socialism, which was never realized, and the shame

that this carries with it—the shame of being simple, the shame of

being a worker, the shame of being poor—this is what makes him

silent.

I hope she is not the new Rimbaud and will not resort to the all-toopowerful

protest of… silence. There is an anti-poetry in her aesthetic,

an ability to write in a willfully unpoetic manner, making

misconnections, dredging the unconscious, breaking rules, extreme

but controlled emoting. It is sometimes close to prose, to speech, but

turns again to the intrinsically poetic, the profound nuance of what

hasn’t quite been said before. She finds the ‘third way’ between

agitprop and solipsism. She manages the very real, the very dream.

There is confrontation but also mystery. Enigma smiles from the

lines. A first full English collection will be an event. Perhaps it is key

that the translator is as politically savvy as the author and that there is

a shared concern beyond the poetry.

I’ll write you!

directly into the abyss,

where the angels dig the earth,

where enjoyment

cuts through desire like a crimson bough.

this blood soaks straight into the letter,

and the roses under my window

are beating their drums at night.

Niall McDevitt

.