Tuesday. 2nd June. Evening. Exarchia.

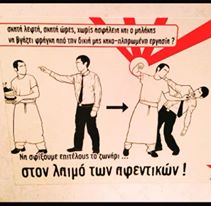

In a small bar called Mikro, I am particularly struck by this sticker above the toilet with a distinctly Maoist aesthetic. On the left it depicts a faceless waiter being harangued by his tie-wearing boss. An arrow points righteously to the next frame, in which that very same worker has dropped the dishes and is waving a fist – now with shafts of red light fantastically exploding from it – right in the managers face! I think of many friends back home: such a sticker is much needed in the U.K.

K- and I drink, with the double joy of not only being in a foreign city, but also in an area loudly proclaiming its rich history of a certain politics that are kept quiet about at home. Exarchia’s wild marginalia – stickers, graffiti, murals, broken marble, hidden mosaics, burnt edges of buildings – is everywhere clogged up like a saturated palimpsest, counter-history seeping out like the plumbing accidents all too common here, and everyone and everything very dramatic.

A radical journalist Elsa arrives for our meeting, we’ve been put in touch by another Greek friend. “I chose this place for a reason” she declares “it is a collective, an anarchist space, a place for radicals.” Proving the fact, throughout the evening various tables of people around us would be gestured to as the authors of a documentary or communique relevant to our discussion. We enter into a long and increasingly passionate discussion jumping from gender politics amongst anarchists, to the impotencies of Syriza, to Greece, to ideology. Her calm and determined way of talking, yet blatantly playful fondness of things, reminded me of a particularly emotive interview from “Utopia on the Horizon” by ROAR Collective that I felt neatly contrasted that classroom scene in Donnie Darko where the hyper-American bitter high-school teacher/self-help guru dupe says something like “there are two poles of emotion – fear, and love – and you must choose between the two”. In ROAR’s film, a Greek mathematics teacher describes first witnessing the horrific spectacle of police brutality, and what an intense incitement to act that is: “There are two poles of emotion – rage and love – and, in a situation like that, you must choose both”.

Anarchists here do not consider themselves leftists, as leftism is associated with statist politics. ‘Communist’, too, has Stalinist connotations. To evade the translation barrier while discussing different tendencies, I suggest ‘radicals’ as an inclusive alternative. Elsa clearly thinks of this as a bit silly, but she entertains the idea for our purposes. As a part-time clown at children’s parties, she is trained in such matters. I think she believes my view of Greece is too charitable with the specifics and too romantic with the generalisations. Greeks, like any people, are suspicious of glowing descriptions of their everyday life. But in this respect I’m willing to appear naive. I honestly am amazed by their achievements, and also think that sense of wonder is mostly appreciated by people here, even if they find it a tad incomprehensible.

Not that people are not incredibly engaged. Elsa told us a story about a famous occupation I’d read about, but not in depth. In June of 2013, the state broadcaster ERT (Greece’s BBC) was shut down at the behest of the Troika’s austerity demands, laying off over 2,600. A large number, freshly unemployed, promptly occupied the studios and ran their own autonomously organised, fierce and liberated media. With, at times, over a million viewers, this experiment in worker-run media was one of the largest of its kind. Then, early one November morning, under direct orders from the government, riot police raided the building. In the final moments of the last broadcast, journalist Nikos Tsimpidas gave a final speech calling for mass revolt against “this virulent repression, this rewind through decades, for all the things we should have stood up for but couldn’t…” Then, as the police were entering the studio, he spoke gravely: “Even words lose their meanings. Are these your orders? Yes, those are my things… The voice of Greek radio falls silent. Good luck to everyone. We’ll find each other, we’ll meet again. These microphones are shutting down. Deep soul.” This sign off, ‘deep soul’ – in Greek psihi vathia – sent a chill through the country. As the emotive parting between leftist partisans, it evoked the trauma of the Civil War years. The way Elsa described it, the timing of this phrase was brutal. Thousands of people burst into tears. Elsa too, merely recounting the story, became teary, as did K- and I on hearing it.

As the night goes on, Elsa realises she must rush off to the weekly meeting of a group she’s a part of. It’s an open assembly, and so although in Greek, she invites us to come watch, just to gather the vibe. The group is called Katalipsi ESIEA, taking their name from the 2009 occupation of the headquarters of The Journalists’ Union of Athens (ESIEA). Disgusted at the media’s response to the 2008 revolt, a group of media workers declared “we are on the side of the rebels…the fire of December won’t be put out, not by bullets and acid against activists, nor by the ideological terrorism spread by the media these last few days.” The inability of the traditional media to even remotely capture the multiplicity of actions back then, the powerful disgust borne from seeing one’s movement so misrepresented, and the the increasing prominence of alternative and relatively unmediated forms of communication, notably Indymedia, created a climate in favour of a total rejection of the bourgeois media. They became, more than ever before, the enemy. As such, many of the revolted – revolted, being common parlance describing those involved in the revolts – solidified into assemblies like this that created alternatives. This group in particular was focused on media campaigns. For example, when a protest is going on, somebody will stay at a computer at home, on the phone to various comrades feeding back live updates, to be updated onto the blog.

After weaving our way through various streets and passages, we arrive just as the meeting is starting – an hour after schedule, at 11pm. It’s in a strip-lit basement room, with little windows at the top-sides of, that occasionally kids peep through. There is chain smoking going on. The walls are white and bare, with the odd anarchist poster. What I assume to be radical literature (most of its in Greek) lies about on the bookshelves in the corner. On entry, Elsa introduced me, letting people know I was trying to make a documentary. This aroused suspicion, and rather unexpectedly, but perhaps helpfully, I had to pitch my ideas to the group. My concept (in short) involves no names, or faces, or group affiliations, but only audio recordings of talking about their feelings; about the affective relationship between anti-authoritarians and power structures. The immediate reaction was, what angle are you taking? This guy wanted to know if I was trying to make that gloating, standard issue Liberal point “oh look, these people have jobs, but they say they’re against work. What hypocrites!” The example I gave, to try and show him this was not my view, was “if you go to a university, you’re engaged in a miserable power structure. Even if you burn down your university, you’re still a student there. I want to study how we deal with that dynamic in general.” Thankfully, I can soon retreat and listen.

Various sheets of paper were passed around the circle of about 12 people. Somebody had written a statement condemning a media boss that claimed to have paid his journalists, but actually had not. I didn’t really understand the majority of what was said, but Elsa translated the broad gist. They went through line by line, screaming feedback at each other; corrections, extra information, disagreements. A few times I asked Elsa “oh, what are they disagreeing with?” and she would laugh, “no, they are agreeing!” It was very pleasing to see, for example, the flicker of slight grins around the room when an inside joke was referenced. Perhaps meetings – and even conversations in general – are even more enjoyable if you don’t speak the same language. Regardless, what we saw of their assembly had an incredible energy, and K- and I left dumbfounded, needing to walk off our awe.

Heathcote Ruthven

Athens Diary 3

Tuesday. 2nd June. Evening. Exarchia.

In a small bar called Mikro, I am particularly struck by this sticker above the toilet with a distinctly Maoist aesthetic. On the left it depicts a faceless waiter being harangued by his tie-wearing boss. An arrow points righteously to the next frame, in which that very same worker has dropped the dishes and is waving a fist – now with shafts of red light fantastically exploding from it – right in the managers face! I think of many friends back home: such a sticker is much needed in the U.K.

K- and I drink, with the double joy of not only being in a foreign city, but also in an area loudly proclaiming its rich history of a certain politics that are kept quiet about at home. Exarchia’s wild marginalia – stickers, graffiti, murals, broken marble, hidden mosaics, burnt edges of buildings – is everywhere clogged up like a saturated palimpsest, counter-history seeping out like the plumbing accidents all too common here, and everyone and everything very dramatic.

A radical journalist Elsa arrives for our meeting, we’ve been put in touch by another Greek friend. “I chose this place for a reason” she declares “it is a collective, an anarchist space, a place for radicals.” Proving the fact, throughout the evening various tables of people around us would be gestured to as the authors of a documentary or communique relevant to our discussion. We enter into a long and increasingly passionate discussion jumping from gender politics amongst anarchists, to the impotencies of Syriza, to Greece, to ideology. Her calm and determined way of talking, yet blatantly playful fondness of things, reminded me of a particularly emotive interview from “Utopia on the Horizon” by ROAR Collective that I felt neatly contrasted that classroom scene in Donnie Darko where the hyper-American bitter high-school teacher/self-help guru dupe says something like “there are two poles of emotion – fear, and love – and you must choose between the two”. In ROAR’s film, a Greek mathematics teacher describes first witnessing the horrific spectacle of police brutality, and what an intense incitement to act that is: “There are two poles of emotion – rage and love – and, in a situation like that, you must choose both”.

Anarchists here do not consider themselves leftists, as leftism is associated with statist politics. ‘Communist’, too, has Stalinist connotations. To evade the translation barrier while discussing different tendencies, I suggest ‘radicals’ as an inclusive alternative. Elsa clearly thinks of this as a bit silly, but she entertains the idea for our purposes. As a part-time clown at children’s parties, she is trained in such matters. I think she believes my view of Greece is too charitable with the specifics and too romantic with the generalisations. Greeks, like any people, are suspicious of glowing descriptions of their everyday life. But in this respect I’m willing to appear naive. I honestly am amazed by their achievements, and also think that sense of wonder is mostly appreciated by people here, even if they find it a tad incomprehensible.

Not that people are not incredibly engaged. Elsa told us a story about a famous occupation I’d read about, but not in depth. In June of 2013, the state broadcaster ERT (Greece’s BBC) was shut down at the behest of the Troika’s austerity demands, laying off over 2,600. A large number, freshly unemployed, promptly occupied the studios and ran their own autonomously organised, fierce and liberated media. With, at times, over a million viewers, this experiment in worker-run media was one of the largest of its kind. Then, early one November morning, under direct orders from the government, riot police raided the building. In the final moments of the last broadcast, journalist Nikos Tsimpidas gave a final speech calling for mass revolt against “this virulent repression, this rewind through decades, for all the things we should have stood up for but couldn’t…” Then, as the police were entering the studio, he spoke gravely: “Even words lose their meanings. Are these your orders? Yes, those are my things… The voice of Greek radio falls silent. Good luck to everyone. We’ll find each other, we’ll meet again. These microphones are shutting down. Deep soul.” This sign off, ‘deep soul’ – in Greek psihi vathia – sent a chill through the country. As the emotive parting between leftist partisans, it evoked the trauma of the Civil War years. The way Elsa described it, the timing of this phrase was brutal. Thousands of people burst into tears. Elsa too, merely recounting the story, became teary, as did K- and I on hearing it.

As the night goes on, Elsa realises she must rush off to the weekly meeting of a group she’s a part of. It’s an open assembly, and so although in Greek, she invites us to come watch, just to gather the vibe. The group is called Katalipsi ESIEA, taking their name from the 2009 occupation of the headquarters of The Journalists’ Union of Athens (ESIEA). Disgusted at the media’s response to the 2008 revolt, a group of media workers declared “we are on the side of the rebels…the fire of December won’t be put out, not by bullets and acid against activists, nor by the ideological terrorism spread by the media these last few days.” The inability of the traditional media to even remotely capture the multiplicity of actions back then, the powerful disgust borne from seeing one’s movement so misrepresented, and the the increasing prominence of alternative and relatively unmediated forms of communication, notably Indymedia, created a climate in favour of a total rejection of the bourgeois media. They became, more than ever before, the enemy. As such, many of the revolted – revolted, being common parlance describing those involved in the revolts – solidified into assemblies like this that created alternatives. This group in particular was focused on media campaigns. For example, when a protest is going on, somebody will stay at a computer at home, on the phone to various comrades feeding back live updates, to be updated onto the blog.

After weaving our way through various streets and passages, we arrive just as the meeting is starting – an hour after schedule, at 11pm. It’s in a strip-lit basement room, with little windows at the top-sides of, that occasionally kids peep through. There is chain smoking going on. The walls are white and bare, with the odd anarchist poster. What I assume to be radical literature (most of its in Greek) lies about on the bookshelves in the corner. On entry, Elsa introduced me, letting people know I was trying to make a documentary. This aroused suspicion, and rather unexpectedly, but perhaps helpfully, I had to pitch my ideas to the group. My concept (in short) involves no names, or faces, or group affiliations, but only audio recordings of talking about their feelings; about the affective relationship between anti-authoritarians and power structures. The immediate reaction was, what angle are you taking? This guy wanted to know if I was trying to make that gloating, standard issue Liberal point “oh look, these people have jobs, but they say they’re against work. What hypocrites!” The example I gave, to try and show him this was not my view, was “if you go to a university, you’re engaged in a miserable power structure. Even if you burn down your university, you’re still a student there. I want to study how we deal with that dynamic in general.” Thankfully, I can soon retreat and listen.

Various sheets of paper were passed around the circle of about 12 people. Somebody had written a statement condemning a media boss that claimed to have paid his journalists, but actually had not. I didn’t really understand the majority of what was said, but Elsa translated the broad gist. They went through line by line, screaming feedback at each other; corrections, extra information, disagreements. A few times I asked Elsa “oh, what are they disagreeing with?” and she would laugh, “no, they are agreeing!” It was very pleasing to see, for example, the flicker of slight grins around the room when an inside joke was referenced. Perhaps meetings – and even conversations in general – are even more enjoyable if you don’t speak the same language. Regardless, what we saw of their assembly had an incredible energy, and K- and I left dumbfounded, needing to walk off our awe.

Heathcote Ruthven

By Heathcote Ruthven