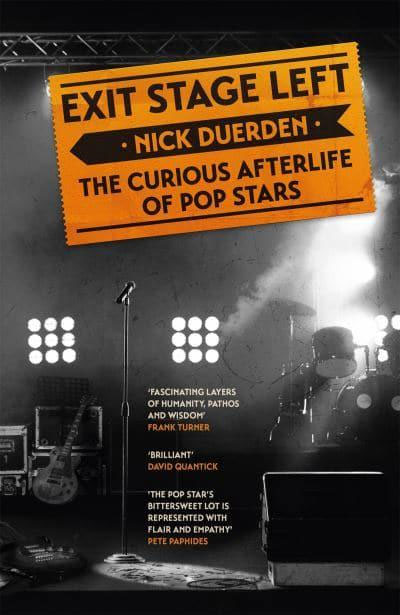

Exit Stage Left: the Curious Afterlife of Pop Stars, Nick Duerden (374pp, £20, Headline)

There are a few wonderful bits of writing in this book. For instance, I especially liked Nick Duerden’s suggestion that Sigue Sigue Sputnik, who aspired to ‘look like the house band on the planet Venus’, actually looked more like ‘a family box of Quality Street chocolates spilled on a pavement in the rain’. In the main however, rather than the ‘candid laugh-out-loud and occasionally shocking look at what happens when the brightest stars fall back down to earth’ the blurb claims, it’s exactly what you expect: a miscellany of drugs, mismanagement, regrets, bullshit, ego, and overspend.

It’s probably just me, but a lot of the artists here don’t strike me as big pop stars – there are a few I’ve never heard of (Damage, Echobelly, Towers of London) – and lots of the ones I have I’d consider minor footnotes in the book of pop, whilst others such as Joe Jackson and Joan Armatrading appear to be doing perfectly well thank you, living on the proceeds from occasional tours and royalties, having readjusted to a world of home-produced and self-released music and online distribution.

But what do I know? I’ve never taken the pop charts seriously, and it didn’t take long to notice how the music papers back in the day (Sounds, NME and Melody Maker) took great delight in tearing apart what they’d proclaimed the future of rock the month before. Yes, I enjoyed watching Reagan and Chernenko wrestle in Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s video for ‘Two Tribes’, and Transvision Vamp’s Wendy James flirting with the world as she pronounced it was time for ‘Revolution Baby’, but real music happened well away from Radio 1 and Top of the Pops. If it was good to see indie kids like The Charlatans and James make it with hit singles, and enjoy KLF’s subversive marketing strategies along with Franz Ferdinand’s appropriation of post-punk, but I really didn’t care about pantomime glamrockers The Darkness (who so wanted to be Queen) or the likes of Dexy’s Midnight Runners and The Stone Roses.

But it seems some people, not least the musicians themselves, took it all very seriously, just as even now naive hopefuls queue up to be verbally abused by Simon Cowell and friends, dressed and moulded as plastic pop, and then spat out of the music machine a few months later if nobody buys their single. I spent most of the time reading this book wanting to shout ‘What did you think would happen?’ at the musicians. Did they really think putting thousands of pounds of cocaine up their noses (or blowing it up each other’s anuses if you were The Charlatans) was better than a savings account? That if you were just a pretty face in the back row of a manufactured band anyone knew or cared who you were or would buy your solo record? Or that releasing what was basically the same single under another name or in a new mix or format would fool anyone? Were stripping-off, speaking your (drug-addled or politically naive) mind, or abusing your fans ever really going to help you in the long-term?

Okay, I’m old and cynical, but I have always been the latter. No-one has ever been able to explain to me why, in the week that NME stated that Billy Bragg’s new UK tour would see him playing for £50 plus accommodation and travel expenses, I was quoted £5000 by his promoter when I phoned them in my capacity as college social secretary. No-one has ever been able to explain why a band like The Boomtown Rats playing recycled Springsteen and Rolling Stones riffs, with a gobby lead singer who moved like Jagger, were called New Wave; or why no-one ever questioned the three rockers who got haircuts and jumpsuits, about their appropriated reggae, bandwagon jumping, and dodgy moniker The Police.

Duerden doesn’t seem that interested in asking questions or challenging assumptions. He naively calls The Only Ones a punk band, when really they were channelling The Velvet Underground (like their occasional support band the very wonderful Wasted Youth) and included several older musicians who had played with bands like Spooky Tooth. The Only Ones were fantastic, on vinyl and live, but their very public flirtation with heroin chic was only ever going to lead where it did for lead singer Peter Perrett: addiction.

Of course, there are some happy endings here, too. My favourite is Dennis Seaton, who used to be in Musical Youth but is now happily chair of the Ladder Association Training Committee who offer practical advice and run safety courses. Billy Bragg still seems pretty rooted too, and has had a second career on the back of his albums with the band Wilco that reinvented the songs of Woody Guthrie for a new generation. David Gray seems almost normal, too, although he still obsesses about his music-making, which he claims to still do all the time, despite finding it agonising and painful. But he seems to have come to terms with it, just as ex Quality Street chocolate, Sisters of Mercy hired-hand and Carbon Silicon member (another band I’ve never heard of) Tony James has. It’s as near to a happy ending as many of the once bigger stars are going to get. Duerden claims that he [James] ‘exudes, as he approaches seventy, the satisfied calm that only comes from those who have lived out their dreams’, whilst James himself wants ‘to be happy and content’, acknowledging that he has ‘actually had a ridiculously successful career’. Which considering the derision which greeted Sigue Sigue Sputnik back in the day, isn’t bad!

I thought this was going to be an in-depth exploration of the effects of fame and how musicians deal or dealt with it. It is, but it’s more Hello! magazine than psychology book. It’s a curiously lightweight volume, rather flat in tone throughout, with only those occasional moments of authorial wit I mentioned at the start of my review to brighten it up. The most sensible comment in the book is in the chapter about folksinger Shirley Collins, where Duerden notes that ‘[t]here is little to suggest that a life without music in it has to be an entirely empty and barren existence’. [p304] But the rest of the book seems to disprove this: on the evidence of this book, pop stars mostly seem to be a curiously self-deluded and dysfunctional bunch of people with not a lot to say, more interested in fame than simply finding an audience for their work, which might have been less damaging.

Rupert Loydell