George Villiers, The Earl of Buckingham, was a ‘favorite’ of King James I. “God bless you, my sweet child and wife,” crooned James,” and grant that ye may ever be a comfort to your dear father and husband.” When James died, his son Charles picked up where dad left off. George had impressed himself upon Charles when teaching him to dance.

In 1623, the couple traveled to Spain to convince the king to give his daughter to Charles in marriage, but thanks to George’s “crassness”, the trip was a failure and they returned to England in a slump. They decided an expedition against the Spanish, in the ‘glorious’ swashbuckling style of Sir Francis Drake, might raise their spirits.

An invasion force was duly arranged.

England had no standing army in those days, so men and boys were rounded up as the need arose. For the majority it was a death sentence: fathers and sons herded off without recourse or appeal, to face unimaginable violence and slaughter, or a slow death from starvation or disease. Of the 12,000 soldiers Charles sent to Germany in 1624, almost 11,000 died without firing a shot.

No organized army meant no organized training, and no organized system of supply, but organized contractors made a killing, short-changing food, uniforms and equipment. Starving soldiers often fought barefoot and those who survived – many maimed for life – were often never paid. Those in command got the job through social standing, not military know-how, and they in turn skimmed off more government money at soldiers’ expense.

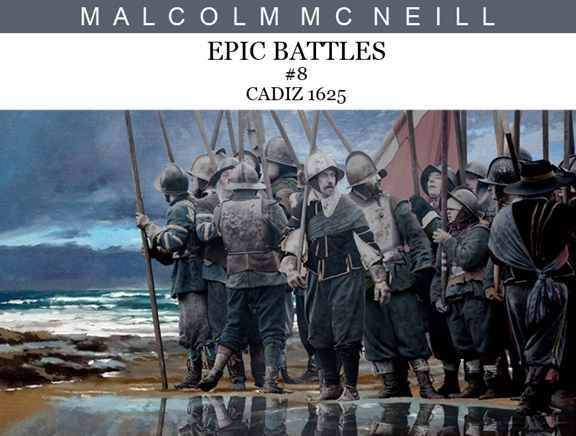

Such a ‘glorious’ arrangement set out for Cadiz in 1625: 15,000 men aboard 100 ships under the now “Lord High Admiral Buckingham”

George was a dancer not a military man, so he assigned Sir Edward Cecil to take charge. “Battle hardened” Cecil had been fighting for the Dutch, and he did know a thing or two about soldiery, but he knew next to nothing about boats. Boats could be as bad for soldiers as battlefields. Losing half an army at sea from lack of food and water or disease was not unheard of.

Much of the fleet went astray in the English Channel due to storms, and when the remainder arrived in Cadiz, it was too depleted, too late, and too disorganized to attack the Spanish treasure galleons, which came and went as they pleased.

The town was unexpectedly well fortified, but Cecil ordered his “rabble of raw and poor rascals” ashore to confront it … without any food or water. In an inspired military moment, he told them to make use of the local wine warehouses instead, then, once they had become utterly drunk and unmanageable, ordered them back to the ships again.

At which point the Spanish attacked and killed them all.

Cheers.

Two years later, George tried to make good by relieving the French town of St. Martin de Re near St. Rochelle. After a clumsy start, the English force finally attempted to scale the walls, but the ladders were too short. Of the 7,000 men and boys that set out, only 2,000 survived.

C’est la guerre.

George and Charles went back their balls.

MALCOLM MC NEILL’s collection of essays, REFLUX was published in 2014 and is available on Amazon.

EPIC BATTLES – TICONDEROGA 1777 is athttp://www.paraphiliamagazine.com/periodical/epic-battles-5-ticonderoga-1777/

Other work in progress, including SCIENCE, can be seen on Facebook –https://www.facebook.com/malcolmmcneillart/