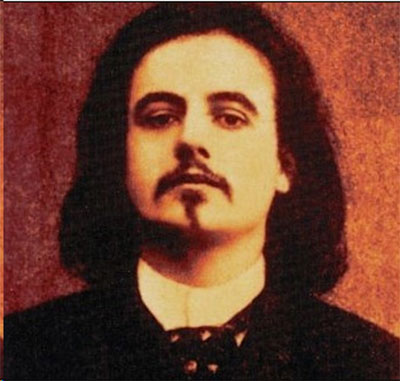

A Note on Alfred Jarry

Modern costumes, preferably, since the satire is modern, and shoddy ones, too, to make the play even more wretched and horrible – Alfred Jarry

In Le Figaro for December 13th 1896, the critic Henri Fouquier denounced a ‘reign of terror exercised by the anarchists of the arts’. The event that inspired his outburst, and many like it, was the premiere of the play Ubu Roi, at the Theatre de l’Oeuvre. The play’s style and presentation were so extreme that critics could only compare its performance to acts of anarchist terror such as those perpetrated by contemporary activists like Ravachol and Auguste Vaillant. During the period March 1892-June 1894 nine people were killed in eleven anarchist bomb attack outrages, the Serbian minister was knifed in the Street and the French President, Carnot, was assassinated.

Fragments of Ubu had appeared in the magazine Echo de Paris as early as 1893, and its author, Alfred Jarry was known as one of the most controversial of the literary avant-garde. Jarry had come to Paris in 1891 to study under the philosopher Bergson. In 1894 an anthology by him entitled Les Minutes de Sable Memorial had been published under the imprint of the Mercure de France. It was illustrated by Jarry’s own woodcuts and contained a number of short prose texts, poems and the Ubu fragment. When the Symbolist movement was beginning to evaporate in the incense-scented mists of mystical transcendentalism Jarry emerged, not a minute too soon as the living embodiment of the most radical aspects of the Decadent tradition: disgust, irony, revolt, grotesque, satire and the absurd. ‘The absurd’, he wrote, ‘exercises the mind and makes the memory work.’

Intent on turning his life into an absurdist pantomime, Jarry soon began contributing sardonic and blasphemous essays to La Plume, La Revue Blanche and Mercure de France. His writing combined the burlesque Chat Noir cabaret Decadent guignol, tradition with the stylized obscurity of Hermetic Symbolism to heighten his sardonic humour – the only response to spleen or universal disgust. As Roger Shattuck has said: ‘…he pushed his sense of the comic into the realm where laughter is mixed with apprehension for ourselves.’

By 1894 Jarry was editing an illustrated revue called L’Ymagier and he had made contact with some of the most illustrious representatives of Symbolism, including Mallarme. He was determined to get his grotesque drama, Ubu produced by Aurelien Lugne-Poe at the Theatre de l’Oeuvre.

Ubu Roi has since become a landmark. The 1896 performance has been seen as not so much the culmination of a revolutionary trend as the outrider of a new spirit of aggressive theatrical modernism – the forerunner of Apollinaire’s Les Mamelles de Tiresias (1917) and the prototype happenings of the Futurists and Dadaists. Indeed from the perspective of history Ubu can be understood as one of the first examples of anti-realistic drama, part of an inexorable stylistic development that was to include Strindberg, Wedekind and Meyerhold and culminate in Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty and the intimate, alienated, drama of Samuel Beckett.

Ubu Roi is the story of a larger-than-life caricature figure, Monsieur Ubu, ‘an ignoble creature so like us all (seen from below)’, or ‘a human blunderbuss who smashed all history as he went’ (Shattuck). He is the embodiment of Jarry’s disgust – a demonic, villainous, amoral, super-bourgeois based on a Monsieur Hébert, Jarry’s old physics teacher. The name ‘Ubu’ derives from Hebert’s nickname: ‘Le Pere Ebe’.

Jarry developed the play from a farce he had co-authored at school and entitled Les Polanais: but he had transformed it and made it entirely his own, using the farcical scenario for his own nihilistic philosophy of the absurd which became, under the name ‘Pataphysics’, a forerunner of Surrealism.

By June 1896 Jarry was working for Lugne-Poe as ‘secretary, scene-shifter and bit-part actor’. By December this play was in production. Jarry devised a grotesque, stylized, mise-en-scene which he described in a letter to the director: a mask for the principal character, a single, all-purpose stage-set, a ‘formally dressed individual’ to indicate scene changes by means of a placard, a special voice for the main character, indeterminate and shoddy costumes. Jarry wished to avoid all the trappings of respectability and outrage his audience by an intrusion of vulgar guignol popular melodrama and puppet theatre. The entire mélange was of course exaggerated by the casual savagery of the scenario: Ubu assassinates the King of Poland, seizes the throne and then massacres everybody else, both aristocrats and peasants. ‘Thus by killing everybody, he must certainly have exterminated a few guilty people in the process and can present himself as a normal moral human being.’ After attending the first performance W. B. Yeats uttered his now much-quoted remark: “What more is possible? After us the Savage God?” With the benefit of hindsight we know that much more was possible. As Simon Watson Taylor has observed, the ‘reign of terror’ was just beginning, and ‘Ubu was to be its prophet.’

Jarry’s guignol theatre implemented, within the magic circle of a theatrical production to intensify the impact, that radical disengagement from normality implicit in frenetique Decadence and Rimbaud’s ‘derangement of the senses’. When considering this project of dislocation one must also take into account another strand of Jarry’s thought: ‘Pataphysics, the ‘Universal Science of Imaginary Solutions’. Between 1894 and 1898 he formulated this doctrine as ‘the science which is superinduced upon metaphysics, whether within or beyond the latter’s limitations, extending as far beyond metaphysics as the latter extends beyond physics.’ Jarry embodied this new universal science in his ‘neo-scientific’ novel The Exploits and Opinions of Doctor Faustroll, Pataphysician, fragments of which appeared in Mercure de France. It was not published in its complete form until after his death.

Book II of Faustroll contains The Elements of Pataphysics. Pataphysics is defined as ‘…the science of imaginary solutions, which symbolically attributes the properties of objects described by their virtuality, to their lineaments.’ The reader is informed that Pataphysics will examine ‘the laws governing exceptions’ and will ‘explain the universe supplementary to this one.’ For the Pataphysician there are different worlds or realities. In another work, Caesar Anti-Christ Jarry wrote: ‘I can see all possible worlds when I look at only one of them. God – or myself – created all possible worlds, they coexist but men can hardly glimpse even one’.

According to Roger Shattuck, Pataphysics is ‘the search for a new reality’. It was an integration of ‘other realities’ with the everyday world, to create a hyper-reality, a new, magical reality to fill the void created by the monstrous Pa Ubu. Ubu himself, it should be noted, was a militant exponent of Pataphysics. Pataphysics is thus a practical application of the freedom of the absurd. Jarry argued that normality is human projection, a cultural construct with no intrinsic validity. But whereas others, like Jules Laforgue could only confront this absurdity with a mask of irony that concealed a desperate pessimism, Jarry seized the opportunity to impose his own counter-normality. The world of Pataphysics is a world manifestly interpenetrated by multiple realities. For the Pataphysician the conventional world is merely accidental data, which, reduced to the status of unexceptional exceptions possess no longer even the virtue of originality.

One facet of the Pataphysical enterprise was embodied in the loathsome, destructive figure of Pa Ubu, whose incarnation in 1896 signified an exemplary act of cultural terrorism. An intermediate facet was embodied in Jarry himself, the court jester to the intelligentsia who embodied the reductio ad absurdam of the Aesthetic ideal of the exemplary lifestyle in his own passionate, daily enactment of his fantasies. Like Nerval before him, Jarry deliberately practiced a ‘reversal of values’ in which dreams were endowed with a value superior to everyday existence. In a novel, Days and Nights (1897) he described this hallucinatory transfiguration of dream and waking. It is an autobiographical account of his military service when he was hospitalized. He cultivated his dreams: ‘his nights became his real life, his days the illusion…’ This is an example of the practice of reversion that is the basis of Decadent perversity and aesthetic nihilism. Pursued with rigor Pataphysics is transformed, as in Ubu Cocu, from a ‘manifest imposture’ into a ‘magnificent posture’. Roger Shattuck: ‘living was no less matter a bluff than of acting… all his writings… circle about the moment of authentic enactment that can make the unreal real and vice versa’.

Pataphysics, like Rimbaud’s ‘derangement of the senses, is founded upon an intuitive understanding of the initiatory significance of imaginative creativity, which, in the freedom of the absurdist Void, engenders a confrontation with Death – Death contains the secrets of transfiguration. By conquering death the poet translates art into an operation that undermines the foundations of normality. That Jarry contemplated these questions is evident from his masterpiece, Faustroll.

Faustroll is an episodic work in the manner of Rabelais. It depicts a journey undertaken by the supreme Pataphysician, Dr. Faustroll, an ‘ultrasexagenerian ephebe’ of bizarre appearance: golden-yellow skin, sea-green mustachios, the hairs of his head alternately platinum blonde and jet black, satyric black fur from groin to feet. Faustroll has two companions: Panmuphle the bailiff, who does all the rowing and a baboon called Bosse-de-Nage whose vocabulary is limited to the words ‘Ha ha’.

Traveling in his boat or skiff, which is also a sieve capable of moving over land and sea, the curious trio embarks on a voyage ‘From Paris to Paris by Sea’ visiting fourteen islands, each dedicated to a significant personality from the Decadent-Symbolist milieu. These include Aubrey Beardsley (‘The Land of Lace’), Emile Bernard (‘The Forest of Love’), Lion Bloy (‘The Great Stair Case of Black Marble’), Gauguin (‘The Fragrant Isle’), Mallarme (‘The Isle of Ptyx’) and Claude Terrasse (‘Ringing Isle’).

Faustroll drowns when he sinks the boat to avoid collision with the great ship Mour-de-Zencle, and all future arts and sciences are revealed inscribed prophetically on his unrolled limbs.

The last section of the book, ETHERNITY (a word which, as Shattuck explains, points to a fusion of ideas concerning the propagation of light, the nature of time and the dimensions of the universe) comprises a telepathic letter from Faustroll to the English physicist Lord Kelvin (William Thomson), thus demonstrating the coexistence of different realities accessible via the gate of death. Faustroll says: ‘I do not think you will have imagined that I was dead. Death is only for common people.’

This telepathic communication from Ethernity is a poetico-pataphysical dissertation derived from Kelvin’s Constitution of Matter (1891, translated into French in 1893). Jarry appropriated sections on electrical units of measurement, the kinetic theory of matter and the wave theory of light. The chapter includes Faustroll’s definition of God (i.e. himself – he had earlier declared, ‘I am God’ in response to the question, ‘Are you Christians?’) which is: ‘…the tangential point between zero and infinity.’

In later years Jarry lost his inheritance on the magazines he was involved with, but he continued to eke out a living by journalism. Although Faustroll was never published during his lifetime, he did write other works: L’Amour Absolu (1899), Messaline (1901), and Le Surmale (1902). In 1903 the magazine Revue Blanche to which he was a regular contributor closed down. As his income slowly dried-up Jarry took to drink in order to keep going and to loosen further the bonds of conventional normality. His program of deliberate absurdity became more and more pronounced. It was as though his personality had become completely possessed by its own fantastic creations. Brabara Wright has called this the ‘Jarry Complex’ – the personality experiences a Surreal repossession of the imagination, an exercise of power over banal normality.

In 1907 Jarry was discovered lying in his room, a mezzanine in a Paris tenement, surrounded by papers and a few totemic possessions – decaying flowers, a stone phallus, two stuffed owls. He was paralyzed in both legs. He died on the 1st of November 1907, aged 34. He had inscribed on the last page of Faustroll the following note: ‘This book will not be published integrally until the author has acquired sufficient experience to savor all its beauties in full.’ As Roger Shattuck put it, Jarry had ‘to experience death in order to catch up with himself’.

When Faustroll was eventually published in 1911 it was hailed by Apollinaire as one of the most significant publications of the year – no one else really noticed.

Bibliography

Jarry, Alfred. Selected Works. Cape. 1965

Jarry, Alfred. Ubu Roi. Gabberbochus Press.1966

Shattuck, Roger. Introduction to Jarry 1965

Taylor, Simon Watson. Alfred Jarry: The Magnificent Pataphysical Posture. Times Literary Supplement, 3 October 1968

Wright, Barbara. Introduction to Jarry 1966

AC Evans

.