The Diggers – Jean-François Millet

Source ~~ Public Domain

Introduction.

There are two classic types of people living in intentional communities. The Dreamers: who spend a lot of time imagining different ways of doing things; and the Diggers: who do the day-to-day work of making it actually happen and therefore, if we take a broad definition of ‘squatting’ to mean more than the material occupation of private property without permission, then we might include within the lineage of squatting movements other examples where resistance has involved an intervention into public space and discourse. In this sense, squatting could be taken to include any direct action where the voiceless and unseen people of the disenfranchised and marginalized have invaded the space of the mainstream in order to place their grievance onto a wider agenda and challenge common sense distributions. As of September 2021 there were 400 ‘intentional communities’ in the UK (most try to distance themselves from the word ‘commune’ and its hippy associations).

Driven by green concerns, house prices and the desire for a simpler existence. Many communes are cohousing set-ups, in which residents live in individual dwellings with a few common areas and domestic functions; others are based upon a lifestyle or worldview (spiritualism, gender non-binarism, veganism) and feature a variety of communal labour arrangements and facilities. The heyday of the 1960’s and 1970’s back-to-the-land and self-sufficiency movements sought to challenge notions of the sanctity of the nuclear family and opt out of ‘the grab-game of straight society’. The Sixties and Seventies communalism was a backlash against hi-tech postwar societies. These movements had a grand vision to change society, often along lines of economic communism and rejected social norms such as monogamy and the concept of traditional childhood.

While, if we take contemporary squatting, for example, these are movements which have mostly been driven by a material necessity to repeatedly challenge the normality of private property, commodification and eviction in major capitalist cities (such as social housing in London, Bristol, etc:).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Part One ~~ From The Peasants’ Revolt To The Great Sunday Squat.

During the Anglo-Saxon period, commoners were able to grow crops and graze their animals, by a system of customary rights, on common land. Traditionally in an English village there were several classes of people. At the lower end were the incomers known as ‘borderers’ or squatters, who would erect a cottage or a hovel on common or waste ground to house themselves and would pay rent to the Manorial lord or would work on his ‘demesne’ several days a week.Over time landowners started to enclose land and deprive commoners of their ancient rights. Farm labourers would lose the ability to feed themselves and were dependent on their Manorial lord for an income. Squatters were made homeless.

In 16th: and 17th: Century Wales, an expansion in population as well as a taxation policy led to people moving into the Welsh countryside, where they squatted on common land. These squatters built their own property under the assumption of a fictional piece of folklore, leading to the developments of small holdings around a Tŷ unnos, or ‘house in a night’.

While there have been many waves of squatting throughout British history, which was a big issue in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 – a major uprising across large parts of England, inspired by Wat Tyler, John Ball, Joanna Ferrour, et. al. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Black Death in the 1340’s, the high taxes resulting from the conflict with France during the Hundred Years’ War and instability within the local leadership of London. – On 30 May 1381, John Bampton was attempting to collect unpaid poll taxes in Brentwood, Essex, when he was met with violent confrontation and the uprising which followed led to the burning of court records, opening jails and demands to end taxation, serfdom and a removal of the King’s senior officials. The name Leveller had previously been used as a term of abuse for rural rebels who had destroyed (‘levelled’) hedges during the Enclosure Riots (beginning with the Kett’s Rebellion in 1549), but it also encapsulated the movement’s ‘levelling’ egalitarian principles. By 1649, The True Levellers / Diggers which had emerged during the bloody maelstrom of the English Civil War, when radicals on the parliamentarian side, the proto-communists of the Diggers and the Levellers, led a movement for the landless folk of England to take over – or ‘squat’ – the commons and fields. Being led by Gerrard Winstanley and William Everard and lasting just under one year, between 1649 and 1650.

‘England is not a free people, till the poor that have no land have a free allowance to dig and labour the commons’ – Gerard Winstanley. ‘The State of Community Opened, and Presented to the Sons of Men’. (1649).

The Diggers continue to be an inspiration for movements challenging norms of private property and inequality today.

‘We raise the watchword Liberty, We will, we will, we will be free’.

George Loveless. 1834.

From 1838, mass meetings in Northern England, the East Midlands, the Staffordshire Potteries, the Black Country, and South Wales spurred a national movement which demanded six democratic reforms outlined in ‘The People’s Charter‘. While seeing these principles as underpinning a fight against political corruption in industrial Britain, the Chartist movement also attracted widespread support for economic reasons (including wage cuts and unemployment). Petitions signed by millions were presented to the House of Commons in 1839, 1842 and 1848 to concede suffrage and when the first petition was refused, preparations began for armed insurrection in Newport, Sheffield and Bradford (which were ultimately quashed). After their defeat in Paris in 1871, exiled Communards arrived on British shores. Their time here forged solidarity across the Channel and left an imprint on British radicalism for decades to come. Due to Britain’s liberal asylum policy at the time, around 3,500 refugees – including 1,500 Communards and their families – arrived in Britain. Fitzrovia was the political centre of much of the Communard community in London. Here French exiles, British radicals and other international refugees created spaces in which to talk politics, swap ideas and explore the intersections of the distinct political cultures of France, Britain and beyond.

In 1896, a group of followers known as the Croydon Brotherhood founded Purleigh, the first community in the United Kingdom governed by the principles laid out by the Russian novelist Tolstoy. In 1897 several members, some from a Quaker background, moved to Leeds. The receipt of a legacy enabled this group to relocate to a seven and a half acre smallholding at Stapleton in 1921. Another Purleigh splinter group established the Whiteway Colony in 1898. These middle-class progressive radical thinkers along with the non-conformist Quaker journalist, Samuel Veale Bracher, built a socialist utopia in the heart of the Cotswolds, rejecting the idea of private property. 125 years later the 41 acre co-operative community at Whiteway Colony, eight miles from Stroud, is still going strong with 150 people calling it home. When Mohandas Gandhi visited in 1909, he saw it as a failed Tolstoyan experiment.

From the ‘Morning Star’ 12 March 1999. – . . . . ‘Files from the 1920’s released to the Public Record Office showed that officials regarded the Whiteway Colony in Gloucestershire as a security risk . . . . . Police paid a husband and wife £400 to infiltrate the commune in the hope of finding evidence of their unspeakable activities. The couple emerged claiming that ‘promiscuous fornication’ was indeed a feature of life in the colony, but they were unable to produce proof. The Home Office could not even work up popular agitation against the commune, as local residents viewed members as cranks rather than as objects of fear’.

Over the years residents have included immigrant anarchists, conscientious objectors and refugees from the Spanish Civil War, as well as co-operative ventures such as Protheroe’s Bakery, the Cotswold Co-operative Handicraft guild and the Co-operative Gardening Group. For a period the anarchist newspaper ‘Freedom’ was produced there by Thomas Keell.

Early settlers building the Colony HallCredit ~~ All Rights Reserved

Early settlers building the Colony HallCredit ~~ All Rights Reserved

Reacting to growing disillusionment with the Suffragist movement, Emiline Pankhurst began to advocate a more assertive and radicalised form of direct action for female suffrage, founding the Women’s Social and Political Union in 1903. The ‘Suffragettes’ (a name coined by ‘The Daily Mail’ as a title of derision but defiantly adopted by the movement, emphasising a hard ‘G’ to render the name ‘Suffrage – Get’) were influenced by tactics used by Russian exiles from Tsarism, such as: hunger strikes, damage to property and vandalism – setting fire to postboxes, smashing windows and detonating bombs, as well as targeting places frequented by men, such as cricket grounds and race tracks – chaining themselves to railings and other public displays of protest.

When Winston Churchill arrived at Bristol Temple Meads on 13 November 1909 he was attacked by Theresa Garnett with a horsewhip who shouted ‘Take that in the name of the insulted women of England!’ Arrested, she was sentenced to a month at HMP Bristol for disturbing the peace. Churchill did not press charges.

The 1918 general election, the first general election to be held after the Representation of the People Act 1918, was the first in which some women (property owners older than 30) could vote. At that election, the first woman to be elected an MP was Constance Markievicz but, in line with Sinn Féin abstentionist policy, she declined to take her seat in the British House of Commons. The first woman to do so was Nancy Astor, Viscountess Astor, following a by-election in November 1919.

The WSPU HQ after being attacked by some 500 undergraduates in Queens Road, Bristol, October 1913

Credit ~~ Bristol Central Library

On 13 July 1906, around 20 unemployed men – known as the Plaistow Land Grabbers, had grown disillusioned with government and local authorities to adequately help them and their families and inspired by the Levenshulme Landgrabbers and those in Bradford, set up the ‘Triangle Camp’ (including a main tent called the ‘Triangle Hotel’) and began cultivation. Their leader, Councillor Ben Cunningham (nicknamed ‘the Captain’), told a local reporter that they ‘wanted to get the people back to the land’ and this ecological theme was emphasized in large white letters at the back of the plot, with the slogan: ‘What will the Harvest be?’ By 4 August the authorities had stepped in.

‘Every Man His Own Owner’ – The Plaistow Land Grabbers

Credit ~~ The Graphic 21 July 1906

People go to Glastonbury for all kinds of reasons, whether it is for the music or spirituality and you would not be the first. Around the turn of the last century early Avalonians – like Dion Fortune, Alice Buckton, Frederick Bligh Bond, Katharine Emma Maltwood, Rutland Boughton and Wellesley Tudor Pole – came seeking the Grail, writing poetry, seeing the stars mirrored in the landscape, composing and performing operettas. The seminal figure who emerged from the shadows to become the prime mover and shaker of everything that followed was shown to be the medic and antiquarian John Arthur Goodchild who died in 1914. Under what seemed to be psychic direction, he placed a curious glass vessel within the waters of a spring outside the town known as Bride’s Well. This took on the character of a kind of ritual enactment, requiring a woman to receive the inspiration to retrieve it. If she did, the world would be changed. In the later stages of this experiment he involved his friend, who bore the dual literary personality of William Sharp / Fiona Macleod. True to Goodchild’s design, the object was indeed recovered as hoped for, and events took on a momentum of their own to draw in such young enthusiasts as Wellesley Tudor Pole and his triad of maidens. Others soon arrived. Newspapers of the time reported that they sometimes scandalised the townspeople. Some warned against letting local children take part in Rutland Boughton’s ‘Glastonbury Festivals’ that took place between 1914 and 1925, believing these eccentric characters with their extra marital affairs, bare feet and corduroy trousers were a pernicious influence. What appears to have motivated them was a powerful desire to make manifest not a personal vision, but a vision of Glastonbury as an important spiritual centre of unity, growth and learning. As can still be seen today.

‘It is to this Avalon of the Heart the pilgrims still go. Some in bands, knowing what they seek. Some alone, with the staff of vision in their hands, awaiting what will come to meet them on this holy ground. None go away as they came. . . .’

Dion Fortune. ‘Avalon of the Heart’.

But where are Glastonbury’s New Avalonians?

Alice Buckton at Chalice Well

Credit ~~ Somerset Heritage Centre

England’s revolutionary reputation was built on the fact that it had experienced not one, but two revolutionary upheavals: the Civil Wars and Interregnum of 1640 – 1660 and the Glorious Revolution of 1688 – 1689. But the seeds of what would lead to major rioting across the UK were sown in the summer of 1918 with strikes across Britain. On 23 August, women cleaners on the railways struck for equal pay with men. A week later the Metropolitan Police went on strike. Due to the dismissal of a Police Constable who was a prominent member of the force and a union organiser, for union activities. The swiftness of the strike and the solidarity of the men shocked the government. By 30 August, 12,000 men were on strike, virtually the entire complement of men in the Metropolitan Force. The Police Strikes during 1918 and 1919 prompted the Government to put before Parliament its proposals for a Police Act, – This act barred police from belonging to a trade union or affiliating with any other trade union body – which established the Police Federation of England and Wales as the representative body for the police. On 1 August 1919, the Police Act of 1919 was passed into law. Two days after the armistice, soldiers in Shoreham walked off their base in protest against officers’ brutality.

Life after the First World War for everyone was tough and Britain found itself in a perilous state – there was a lack of food, housing and young men had perished as they fought for their country. In January 1919, there were mutinies in the British Army and Navy, notably in Folkestone and Southampton, where officers came close to ordering loyal troops to fire on mutineers. Sailors on HMS Kilbride mutinied and raised the Red Flag. – This was not the first time the Red Flag had been used as a symbol of working class rebellion in the United Kingdom, as it was raised during the Merthyr Rising, also referred to as the Merthyr Riots of 1831 which were the violent climax to many years of simmering unrest among the large working class population of Merthyr Tydfil and the surrounding area. Joe Attard. ‘The Merthyr Rising 1831: rage, rebellion and the red flag’. (2 June 2020). – Two thousand soldiers ordered to embark for France mutinied and went on strike. While Conscientious Objectors in several prisons began hunger strikes. January 1919 also saw Police break up an open air trade union meeting where thousands of workers downed tools in demand of a 40-hour week and the Red Flag was flown in George Square, Glasgow. The leaders of the union were arrested and charged with instigating and inciting large crowds of persons to form part of a riotous mob.

1919 also saw a series of race riots which came in the wake of the First World War as the surplus of labour led to dissatisfaction among Britain’s workers, in particular seamen. Britain’s first race riot took place in South Shields. This led to the outbreak of rioting between white and minority workers in Britain’s major seaports, from January to August 1919. These riots were also seen in London, Salford, Hull, Barry and Newport. In June, Cardiff and Liverpool were the scenes of the worst rioting. One person was murdered by drowning in Liverpool Docks. While in Cardiff three people died. The riots of 1919 saw angry mobs consisting of striking rail workers, miners and police, clashing with soldiers in the streets.

On 4 and 5 March, Kinmel Park in Bodelwyddan, near Abergele, North Wales, experienced two days of riots in the Canadian sector of the military complex, which cost five soldier’s lives.

21 April saw fighting between Arabs and English girls at an eating house in Cable Street, London. A number of ex-servicemen entered the place and soon after a fight broke out with revolvers, knives and bottles being used. While a hostile crowd gathered outside. Police arrived but it took some time for them to gain entrance and make arrests.

In May, the Strangers’ Home for Asiatic Seamen in West India Dock Road, London was surrounded by a hostile crowd and any coloured man who appeared was greeted with abuse and had to be escorted by the police. It was necessary at times to bar the doors of the Home.

During the summer of 1919, Luton Town Hall was burned down by rioters, before the army was brought in to impose marital law and restore order. By mid-1919 there were strikes or the threat of strikes on the docks and among railway and other transport workers. There was a nationwide bakers strike and a rent strike by council tenants in Glasgow.

On the August Bank Holiday, the Government in London dispatched tanks to the city of Liverpool in an overwhelming show of force – because police officers were among those on strike – with soldiers deployed to suppress the fierce and violent riots led by British trade unionists and Communists. But, as the Army was unable to contain these mobs, the Government deployed the Navy and battleships could be seen moored in the Mersey, which also came under siege. In Liverpool rioting continued for three or four days before the military, aided by non-striking police, brought the situation under control, but at the cost of several lives and more than 200 arrests for looting.

Industrial unrest and mutiny in the armed forces combined together to produce the fear that Britain was facing the same kind of situation which had led to the Russian Revolution two years earlier. This all took place against the background of a British invasion of Russia and fears in the Government that a revolution was imminent and It appeared that Britain could be on the verge of transforming itself from a constitutional monarchy and liberal democracy, into a Soviet-style People’s Republic.

However, in the early 1920’s the mood shifted away from revolution and overthrowing the Government in a bloody revolt. There were wars abroad – in Iraq and Afghanistan – and a threat of terrorism coming from Ireland in the form of Sinn Fein. The riots therefore subdued as more immediate threats from abroad presented themselves. Nonetheless, 1918 and 1919 were years in which sizeable numbers of people stood up to the power of generals, governments and employers. But with the assembled forces unable to seize state power – something that distinguishes all true revolutions – our rulers were able to restore control and secure lasting victories. The order established endures to this day.

So what prospect is there, really, for another revolutionary crisis in Britain?

Raise the red flag – workers assemble in Glasgow

Credit ~~ Glasgow Times

Perhaps the first ‘underground’ publication was ‘Peace News’ a pacifist magazine that was first published on 6 June 1936 as a free issue to serve the peace movement in the United Kingdom and launched by Humphrey Moore and his wife, Kathleen. The late MP, Tony Benn said of ‘Peace News’, – ‘a paper that gives us hope. . . . (it) should be widely read’. During the late 1960’s / 1970’s the magazine was closely linked to the UK Counterculture scene and underground press. Today, its joint editors are Milan Rai and Emily Johns.

During the summer of 1946, thousands of British families took the law into their own hands to temporarily solve their housing problems by ‘requisitioning’ empty military camps. – An early precedent was set by a group in Brighton known as the Vigilantes who occupied 3 empty homes in July 1945. – This mass-squatting movement was rapid, spontaneous and entirely working-class in character. While it was often driven at ground level by women, the movement soon developed a formal leadership structure dominated by ex-servicemen who had served as NCO’s and Warrant Officers. When and where the squatting movement started remains disputed. But the event that received most publicity on the radio, in the press and on cinema newsreels, was the occupation of an army camp at Chalfont St: Giles in Buckinghamshire.

Bristol, with particularly acute housing problems and a large number of former British and US military sites in and around the city, was one of the leading centres of the squatters’ movement. By early September over 1,000 Bristolians were living in former military huts, something that alarmed the council at first.

Purdown was only one of a number of very similar sites deemed suitable for squatting by Bristolians – others were at a gun site on Bedminster Down and the POW Camp at White City – who were sick of sharing overcrowded housing. The accommodation was spartan. They were usually just wooden huts, sleeping quarters for 10 to 20 people, with slightly more salubrious quarters for officers and NCO’s. There were huts for administration, catering and stores. In all, there were at least 12 at Purdown and now they would have a new use. As the squatters moved in, they elected management committees and collected ‘rent’ from the residents to pay to whichever authority would recognise them as tenants. This was the main reason why there seems to have been little hostility to them from the press or public in Bristol or anywhere else. They made it clear they were not trying to freeload.

As council houses were built and made available over the next few years, most camps around Bristol emptied and tenants moved into proper homes. Although in some places the camps lasted well into the 1950’s and had become formally organised.

POW Camp Squatters, White City, Bristol. August 1946

Credit ~~ Bristol Radical History Group

Known as ‘The Great Sunday Squat’ and following the example of the military bases squatters, the Communist Party – with help from the Women’s Voluntary Service and even some Police Officers – moved over 100 families into luxury flats in Central London, on 8 September. They selected flats which had, in fact, been used for official use during the war. So many families turned up on the day that further squats had to be established, including buildings in Marylebone, Pimlico, and St: John’s Wood.

The government was now under pressure and fearing a spread of direct action, reacted harshly. They arrested 5 leaders of the Communist Party (all elected local councillors) who were imprisoned and charged with the novel offence of ‘conspiracy to trespass’. Police began laying siege and blockading the squats in full view of the media, cutting off facilities and preventing food and supplies from reaching them. The cabinet also instructed the Home Office to draft a new law that would make squatting a criminal offence and guards were placed in empty buildings across the city.

The squats crumbled within a matter of weeks and plans for criminal legislation were dropped. The squatters at the Duchess of Bedford House – who had been the high-profile media example of the activity – left on 20 September accompanied by a marching band.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Part Two ~~ Counterculture And Beyond.

A Counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behaviour differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores. A countercultural movement expresses the ethos and aspirations of a specific population during a well-defined era. When oppositional forces reach critical mass, countercultures can trigger dramatic cultural changes. Prominent examples of countercultures in the Western world include the Levellers (1645–1650) – see above, Bohemianism (1850–1910) – the practice of an unconventional lifestyle, often in the company of like-minded people and with few permanent ties. It involved musical, artistic, literary or spiritual pursuits (The Bloomsbury Group), the more fragmentary counterculture of the Beat Generation (1944–1964) – the central elements of Beat culture were the rejection of standard narrative values, making a spiritual quest, the exploration of American and Eastern religions, the rejection of economic materialism, explicit portrayals of the human condition, experimentation with psychedelic drugs and sexual liberation and exploration (Ginsberg, Burroughs, Kerouac, et al), followed by the globalised Counterculture of the 1960’s (1964–1974) – the UK’s underground movement was focused on the Ladbroke Grove / Notting Hill area of London.

Founded in 1961, ‘Private Eye’ has run rings around the establishment for decades; refusing to swallow their bullshit, exposing sleaze and providing one of the rawest and unfiltered critiques of British society and has been edited by Ian Hislop since 1986. The magazine has long been known for attracting libel lawsuits, which in English law can lead to the award of damages relatively easily.

‘Militant’ was a Socialist newspaper that ran from 1964 until 1997. During the ’70’s you could buy the newspaper on the factory floor.

Counterculture is sometimes conceptualised in terms of generational conflict and rejection of older or adult values. It may or may not be explicitly political. But, typically involves criticism or rejection of currently powerful institutions, with accompanying hope for a better life or a new society and is evident in literature and music of the time.

‘Radio Caroline’ and ‘Radio London’ were British radio stations founded in 1964 initially to circumvent the record companies’ control of popular music broadcasting and the BBC’s radio broadcasting monopoly. Both unlicensed by any government, they were classed as pirate radio stations that never became illegal as such due to operating outside any national jurisdiction, although after the Marine Offences Act (1967) it became illegal for a British subject to associate with them. ‘Radio London’ closed down on 14 August 1967 and ‘Radio Caroline’ followed on 3 March 1968.

Apart from publications such as ‘IT’ – The first copy was on 15 October 1966. Having had various editors in its history, the magazine first ceased publication in October 1973 after being convicted for running contact ads: for gay men. In 2011, ‘IT’ was relaunched as an online magazine with Nick Victor as the current editor – and ‘Oz’ – co-editors – Richard Neville, Martin Sharpe and Jim Anderson. Felix Dennis replaced Sharpe in 1969. UK Music Critics hated Led Zeppelin, but Dennis writing in ‘Oz’ March 1969 stated: ‘Very occasionally a long-playing record is released that defies immediate classification or description, simply because it’s so obviously a turning point in rock music. . . .’ ‘Oz’ was one of several underground publications targeted by the Obscene Publications Squad. The last issue was published in November 1973, both of which had a national circulation, the 1960’s and 1970’s saw the emergence of a whole range of local alternative newspapers, which were usually published monthly. These were largely made possible by the introduction in the 1950’s of offset litho printing, which was much cheaper than traditional typesetting and use of the rotary letterpress. The underground press offered a platform to the socially impotent and mirrored the changing way of life in the UK underground. Neville published an account of the counterculture called ‘Playpower’, in which he described most of the world’s underground publications. He also listed many of the regular key topics from those publications including Vietnam, Black Power, politics, police brutality, hippies and lifestyle revolution, drugs, popular music, new society, cinema, theatre, graphics, cartoons, etc:

‘Revolution must break with the past, and derive all its poetry from the future’.Situationist International.

(Quoted in ‘Playpower’ 1970).

During the 1970’s Smith and Logan from the ‘New Musical Express’ raided the underground press for writers and started to champion underground, up-and-coming music, political articles and became the gateway to a more rebellious world for the nation’s listless youth.

A 1980 review identified some 70 such publications around the United Kingdom but estimated that the true number could well have run into hundreds. – ‘Bristol Voice’, ‘Seeds’, etc: – Such papers were usually published anonymously, for fear of the UK’s draconian libel laws. They followed a broad anarchist, libertarian, left-wing of the Labour Party, socialist approach but the philosophy of a paper was usually flexible as those responsible for its production came and went. Most papers were run on collective principles.

As with the Beat Generation of the 1950’s and their interest in Eastern religion, notably Zen. When the Beatles visited India during February 1968 to study Transcendental Meditation, there was a rapid expansion in interest in Hinduism. Young people were already heading east on the so-called ‘Hippie Trail’, – the name given to the overland journey taken by members of the hippie culture and others from the mid-1950’s to the late 1970’s between Europe and South Asia – looking for spiritual enlightenment and an escape from the material lifestyle of the West.

With the advent of the 1960’s in the midst of a housing crisis, communes and squats became more frequent.

In Scotland, the Findhorn Foundation which was founded by Peter and Eileen Caddy with Dorothy Maclean in 1962, has become prominent for its educational centre and experimental architectural community project based at The Park, near the village of Findhorn. The Ecovillage community and that at Cluny Hill in Forres, now house more than 400 people.

Since 1967, the Principality of Sealand has existed as an unrecognised micronation on HM Fort Roughs, a sea fort off the coast of Suffolk. It was occupied by Paddy Roy Bates who styled himself as His Royal Highness Prince Roy.

1968 would become the year of unrest.

The protests of 1968 comprised a worldwide escalation of social conflicts, predominantly characterised by popular rebellions against state militaries and the bureaucracies. During the summer of that year, a couple of French students, whose visas had run out, took to the night-time streets of Yeovil – a country town at heart, along with local teenagers after closing time at the Half Moon in Silver Street, to re-enact the Paris disturbances of May that year – where a period of civil unrest had occurred throughout France, lasting some seven weeks and punctuated by demonstrations, general strikes, as well as the occupation of universities and factories. At the height of events the economy of France came to a halt. – Several youths were arrested after causing damage to shop windows and the Yeovil Police Station. On 27 October thirty thousand demonstrators marched through London in protest against the Vietnam war which became a riot when police charged the crowd with horses.

Students at universities around the UK and the world took part in a series of protests that challenged the hierarchy of universities, corporations and governments. They were following the actions of their French peers, who occupied the streets of Paris from 3 – 13 May and were later joined by workers in the largest general strike of the 20th: Century, with seven million people downing tools. The unrest shook up the status quo and the student movement gained momentum.

Months after those original protests and following allegations that Bristol University students were unable to control their own union, this led to a protest over one weekend. At this time the vice-chancellorship had passed to John Harris who was said to be nonplussed by the protest. However, he died one week later after collapsing in his office. Further disagreement between the university and the student union occurred over the issues of giving greater representation on university bodies and ‘reciprocal membership’ of the union, meaning that any students from Bristol – including those studying at Bristol’s technical and vocational colleges – would have access to the facilities of the newly-opened £750,000 University of Bristol Students’ Union building. This escalated into an 11-day sit-in at the Senate House on Tyndall Avenue after a march through Bristol on 5 December, which gained Bristol national headlines.

It was the first ever large-scale student protest at the university and local students were joined by contingents from LSE, Birmingham, Leicester, Cardiff and other universities. Over the course of the protest more than 700 students, of a total of 6,000 studying at the time, joined the sit-in, which ended with eight students receiving court summons’ and being banned from entering the building. Even the police were sympathetic to the student cause. But, when 16 December came, most students had left for the Christmas holidays and therefore the sit-in crumbled.

Student Protest March. Bristol

Student Protest March. Bristol

Credit ~~ © Tony Byers

‘Ev’rywhere I hear the sound of marching charging feet, boy

‘Cause summer’s here and the time is right for fighting in the street, boy. . . .’

‘Street Fighting Man’. Mick Jagger. 1968.

While many trace the history of London’s contemporary squatting movement back to 1968, the seeds were sown well before then. In 1969, members of the London Street Commune squatted in a mansion at 144, Piccadilly in Central London to highlight the issue of homelessness but were quickly evicted. The Eel Pie Island Hotel was occupied by a small group of local anarchists including illustrator Clifford Harper. By 1970 it had become the UK’s largest hippy commune and housed up to 100 residents before a mysterious fire in 1971 burnt the hotel to the ground. Communes had sprung up due to hippy values during the mid to late 1960’s, where a large gathering of people shared a common life, common interests, common values and beliefs, as well as shared property, possessions, resources and in some communes, work, income or assets. While St: Agnes Place was a squatted street in Kennington, South London, which was occupied from 1969 until 2005.

By the early 1970’s, there was a growing conflict between the original activists of the Family Squatting Movement and a newer wave of squatters who simply rejected the right of landlords to charge rent and who believed, or claimed to, that seizing property and living rent-free was a revolutionary political act or more practically decided it was a good way to save money.

Birchwood Hall Community was founded in 1970 by a group of people interested in exploring alternative lifestyles. The community has gone through many changes since then, but for most of the time has existed as a largely stable and harmonious group. The main building at the community is a large 19th: Century red brick house located just north of the Malvern Hills. In addition to the ‘Hall’, where most members currently live, there is a Coach House which is home to several more members and is currently being developed to provide further residential space. There are also a number of barns and outbuildings which both houses share. Some of these buildings have been restored and converted to create workshops while others are awaiting restoration. There is also a small residential centre called ‘Anybody’s Barn’, which is operated as a separate charity by members of the community, providing space for residential or day retreats, courses, meetings and workshops for a variety of groups and organisations, which are all located in eight acres of grounds. In legal terms it is a housing co-operative, governed by regulations which are based on standard ‘Co-operative Society Rules’. The land and buildings are owned by the co-operative (which includes all residents) and not by any one individual. If the co-op ceased to exist entirely, money from the sale of the property would be distributed to charities and / or to other intentional communities with similar aims. Most community members have some form of paid employment. Politics is important to the group, broadly being left-wing and feminist in approach. The community has political ideals, but perhaps not an idealistic view of political change. They are not as closely involved with the rest of the Communes Movement as they used to be, but that could change in the future.

Birchwood Hall

Birchwood Hall

Credit ~~ Birchwood Hall Community

By the early 1970’s Counterculture as a visible and global phenomenon was beginning to diminish and fade. Some people had lost faith in peaceful change and were moving to extreme left wing political and even terrorist beliefs – The Angry Brigade decided to launch a bombing campaign with small bombs, in order to maximise media exposure to their demands while keeping collateral damage to a minimum. The campaign started in August 1970 and continued for a year until arrests took place the following summer. Targets included banks, embassies, a BBC Outside Broadcast vehicle and the homes of Conservative MP’s. In total, police attributed 25 bombings to the Angry Brigade. The bombings mostly caused property damage; one person was slightly injured – and while much has been written about the decline of Counterculture, in reality, it never really went away.

‘The thing the sixties did was to show us the possibilities and the responsibility that we all had. It wasn’t the answer. It just gave us a glimpse of the possibility’. – John Lennon. Source ~~ Interview for KFRC RKO Radio (8 December 1980).

During 1973 – 1975 near Euston Station in Central London, Tolmers Square was occupied by more than one hundred squatters, who engaged with local groups to fight for a redevelopment plan which fitted the community. After a long struggle, they were successful.

Tipi Valley is situated high in the hills of South-West Wales. The community has been buying it field by field since 1975. In this time, the oldest fields have regenerated from sheep farming land to mixed deciduous woodland rich in wildlife. It is a wild valley dotted with homes that are low impact dwellings – tipis, yurts and turf roofed round huts.

Frestonia was the name adopted by the residents of Freston Road in London, when they attempted to secede from the United Kingdom in 1977 to form the Free and Independent Republic of Frestonia. Most of the residents of Freston Road were squatters, who had moved into empty houses in the early 1970’s. The Republic of Frestonia continued to operate as a collective well into the 1980’s, becoming a creative hub for writers, artists and musicians as well as cultural activists. During a split between members, the remaining Frestonians proved incapable of maintaining the ideals of the Frestonian ‘nation’, which consequently went into decline. In its place, a more conventional local community developed, without any claims to secession from the UK.

The Argyle Street Alternative Republic in Norwich housed more than 200 people from 1979 until 1985, when it was evicted and demolished. Elsewhere in England, there were sizeable squatting communities in Brighton, Cambridge, Leicester, Manchester and Portsmouth. Many squatters legalised their homes or projects in the 1980’s, for example Bonnington Square and Frestonia in London. The 121 Centre was set up on Railton Road in Brixton, London, having first been squatted by the black feminist Olive Morris. Until eviction in 1999, the 121 Centre hosted events and in the 1980’s printed a squatters newspaper called ‘Crowbar’ and the anarchist ‘Black Flag’ magazine in its basement.

During the 1980’s New Age Travellers who lived in mobile homes – generally old vans, trucks and buses (including double-deckers) – moved in convoys. One group of travellers came to be known as the ‘Peace Convoy’ after visits to Peace camps associated with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. The movement had faced significant opposition from the British Government and from the mainstream media, epitomised by the authorities’ attempts to prevent the Stonehenge Free Festival – which ran from 1974 to 1984 was a celebration of various alternative cultures. The Tibetan Ukrainian Mountain Troupe, The Tepee People, Circus Normal, the Peace Convoy, New Age Travellers and the Wallies of Wessex were notable Counterculture attendees – and the resultant Battle of the Beanfield, which took place on 1 June 1985 – resulting in what was, according to the ‘Guardian’, one of the largest mass arrests of civilians since at least the Second World War, possibly one of the biggest in English legal history. In 1986 and later years police again blocked travellers from ‘taking the Stones’ on the Summer Solstice. This led Travellers to spend summers squatting by the hundreds on several sites adjacent to the A303 in Wiltshire. Following the crackdowns against aspects of New Age Traveller culture and the ‘Free Festivals’, some ceased travelling altogether and others headed to continental Europe to pursue a continuance of the lifestyle.

Tinkers Bubble, which was established in 1994, is an off-grid community on 40 acres of land in rural Somerset. The name comes from the spring that flows through the woodland ending in a small waterfall by the road. This is where gypsies brought their horses to water them at the bubble; the gypsy name for a waterfall.

Founded by Paul and Hoppi Wimbush, the Lammas project was created to ‘pioneer an alternative model for living on the land’. In 2009, 76 acres of land were bought in Pembrokeshire to create a sustainable eco-village.

Occupy London was a political movement and part of the International Occupy Movement. While some media described it as an ‘anti-capitalist’ movement, – Caroline Davies. ‘The Guardian’ – in the statement written and endorsed by consensus by the Occupy assembly in the first two days of the occupation, occupiers defined themselves as a movement working to create alternatives to an ‘unjust and undemocratic’ system. A second statement endorsed the following day called for ‘real global democracy’. Due to a pre-emptive injunction, the protesters were prevented from their original aim to camp outside the London Stock Exchange. A camp was set up nearby, next to St: Paul’s Cathedral. On 18 January 2012, Mr: Justice Lindblom granted an injunction against continuation of the protest, but the protesters remained in place pending an appeal. The appeal was refused on 22 February and just past midnight on 28 February, bailiffs supported by City of London Police began to remove the tents. Occupy Bristol camped-out on College Green between the Council House and Bristol Cathedral from October 2011 until January 2012.

Extinction Rebellion is a global environmental movement, with the stated aim of using nonviolent civil disobedience to compel government action to avoid tipping points in the climate system, biodiversity loss, and the risk of social and ecological collapse. Extinction Rebellion was established in Stroud during May 2018 by Gail Bradbrook, Simon Bramwell and Roger Hallam, along with eight other co-founders from the campaign group Rising Up!

In Britain in 2021 some campaigners considered that XR was being ignored by the government (except for legislating against protests) and no longer had the effect needed to create real change, so other groups were formed with the idea of using mass disruption and arrest to draw attention to a very specific demand. Insulate Britain was set up to demand that the government implement measures to fit all homes with improved insulation by 2030 to improve energy efficiency thus reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Just Stop Oil from 2022 protested against fossil fuels. Both groups have carried out disruptive protests, blocking traffic and seeking to be arrested.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Part Three ~~ Bristol: Riots, Squats & Free Festivals.

But what of Bristol – already mentioned above – and its self-image nowadays – the radicalism, creativity, environmentalism, the woke progressiveness and on sunny days, the low-lying smog of skunk – it would be reasonable to assume that Bristol in the 1960’s was the San Francisco of Western Europe, right? Well, no.

Noted for its riots. (There have been eleven in total since 1793, with the latest in March 2021). The earliest being the Bristol Bridge Riot of 1793. In 1794 the populace of Bristol were said to be ‘apt to collect in mobs on the slightest occasions; but have been seldom so spirited as in the late transactions on Bristol-bridge’. – Matthews. ‘The New History, Survey and Description of the City and Suburbs of Bristol, or Complete Guide’. Printed 1794. The Bristol Bridge Riot of 30 September 1793 began as a protest at renewal of an act levying tolls on Bristol Bridge, which included the proposal to demolish several houses near the bridge in order to create a new access road and controversy about the date for removal of gates. Eleven people were killed and 45 injured, making it one of the worst massacres of the 18th: Century in England. – Manson. ‘Riot! The Bristol Bridge Massacre of 1793’. Printed 1998. Other riots have been the New Cut Riot, 1809. Where a celebratory dinner ended in a mass brawl between English and Irish labourers and ended in a riot which had to be suppressed by a Naval press gang. – Latimer. ‘The Annals of Bristol in the Nineteenth Century’. 1887. The 1831 Bristol Riots (Queen Square Riots) took place between 29 – 31 October and were part of the 1831 Reform Riots. – There were also civil disturbances in London, Leicester, Yeovil, Sherborne, Exeter, Bath and Worcester along with riots at Nottingham and Derby. – The riots arose after the ‘Second Reform Bill’ was voted down in the House of Lords. Four rioters were killed and 86 were wounded. 100 of those involved were tried in January 1832 and despite a petition of 10,000 signatures, four men were hanged. Old Market Riot, 1932. On 23 February, in reaction to the government reducing unemployment benefit by 10 per cent, around 4,000 protestors tried to march down to the city centre, led by the National Unemployed Workers Movement. The Park Street Riot occurred in Park Street and George Street on 15 July 1944. Racial tensions inflamed by earlier incidents and the racial segregation of GIs both in the UK and abroad, came to a head in Bristol when a large number of black GIs refused to go back to their camps after US Military Police came to end a minor fracas. St: Pauls have had two riots, 1980 and 1986. There have also been riots in Southmead (1980), Hartcliffe (1992), Stokes Croft (April 2011), part of the National Riots (August 2011) and the Kill the Bill Protest (21, 23 and 26 March 2021) against the ‘Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022’, which all ended violently and a number of the rioters being jailed.

There have been Anarchist and Socialist bookshops in Bristol since the 1920’s, perhaps even earlier.- Flynn’s, People’s Bookshop, Kingswood Bookshop, Black River Books, Main Trend Books. – A strange mix of Hippies and Hell’s Angels at The Last Homely House, Hotwell Road – the name was taken from Elrond’s dwelling in Tolkien’s ‘The Lord Of The Rings’ – during the late 1960’s, where one could buy the latest copies of ‘OZ’, ‘IT’ and ‘Gandalf’s Garden’ – although they preferred to be called Overground and ran for six issues from 1968,- imported albums from America, clothes and other odds and ends. It would later move further into Hotwells and become Where The Wild Things Are, a bookshop for children. – The name comes from Maurice Sendak’s children’s picture book of the same name and published in 1963.

The Last Homely House. Hotwells

The Last Homely House. Hotwells

Credit ~~ All Rights Reserved

St: Paul’s Carnival is an annual Caribbean Carnival held, usually on the first Saturday of July, in St: Paul’s, Bristol. The celebration began in 1968 as the St: Paul’s Festival, in order to improve relationships between the European, African, Caribbean and Asian inhabitants of the area.

Called the St: Paul’s Carnival since 1991, the event includes a masquerade procession with ornate and colourful costumes and floats from local schools and cultural associations, a stage for professional performers, sound systems in neighbouring streets and a range of stalls selling food from a wide range of cultures.

St: Paul’s Festival. 1968

St: Paul’s Festival. 1968

Credit ~~ All Rights Reserved

Late 1970 saw an anarchic commune at 49, Cotham Road which had links to the ‘Black Dwarf’ a political and cultural newspaper that ran from 1968 until 1972 and associated with the International Marxist Group, while various other small communes had also started to spring up at this time.

During the 1970’s there were four ‘alternative shops’ selling various items from books, magazines and paraphernalia. One was at St: Nicholas Market, two on Perry Road – Pentacle Books and Taro, along with Medina at Lower Park Row.

Largely populated with people in their late teens and early twenties, who were often characterised as rebellious youth, disenchanted ‘dropouts’ who had rejected the values of mainstream religion and culture to create their own Counterculture and protest movements. Their enthusiasm for Asian mysticism, new forms of psychotherapy, or new fervent expressions of evangelical Christianity led them to join exciting new religions in the hope of experiencing the numinous, finding the authentic self, or transforming the world and themselves, which would lead the mainstream media to brand them as ‘cults’ and became the single most important influence on people’s attitudes towards them. Bristol would see many ‘cults’ spring up during the 1970’s. Hare Krishna devotees spreading the word in Broadmead to shoppers and workers alike, in 1971. Scientology books were banned from sale by Georges Bookshop at the top of Park Street in the early 1970’s. Although it was not long after, that Scientologists were targeting the bookshop by leaving books on the shelves for people to buy. Mid-1974, Divya Sandesh Parishad. A strange meeting at the crossroads, with Premies of Guru Maharaj Ji. Their commune was at 103, Belmont Road. Exegesis were a group of individuals that delivered the ‘Exegesis Programme’ through an ‘Exegesis Seminar’. The alleged end result of the programme was individual enlightenment, a personal transformation. Seminars were run at Arley Chapel, now a Polish Roman Catholic Church during the late 1970’s / early 1980’s. Although not in itself a religion or belief, the programme was popularly interpreted as such. See George D. Chryssides. ‘Exploring New Religions’. (12 November 2001). The Cult Information Centre categorised it as a ‘therapy cult’, focused on personal and individual development. The Home Office asked the Metropolitan and Avon and Somerset police to investigate Exegesis. Although the police brought no charges, Exegesis ceased to run seminars around 1984.

The Ashton Court Festival was an outdoor music festival held annually in mid-July on the grounds of Ashton Court, just outside Bristol. The festival was a weekend event which featured a variety of local bands and national headliners. Mainly aimed at local residents, the festival did not have overnight camping facilities and was financed by donations and benefit gigs.

Starting as a small one-day festival in 1974 called the Bristol Community Festival, the festival grew during succeeding years and was said to be Britain’s largest free festival until changes brought on by government legislation resulted in compulsory fees and security fencing being introduced. In 1986, Hawkwind, whose fluid line-up of members were in the habit of just showing up at festivals and events around the country, arrived at Ashton Court. They were turned away by the festival organisers. Telling the band that they were not welcome. The organisers of the festival declared bankruptcy in 2007.

Bristol’s Stokes Croft road cuts a gnarled, paint-splattered route north from the city centre. To the east runs St: Paul’s, home to the city’s historically Jamaican community and the location of notorious riots in the 1980’s and to the west sits affluent Kingsdown. In the empty spaces left derelict long after World War Two, a thriving counter-cultural scene blossomed, starting with the punks in the mid-70’s and evolving into the festival and alternative art communities of the late-1990’s and beyond. The squats created a space for parties, performances and exhibitions – and one where artists could live and work without worrying about making rent. The graffiti-sprayed buildings changed the aesthetic of the area and inevitably, the neighbourhood became fashionable, creeping up in price. In the early 1980’s the area was desolate. There was nothing going on apart from the punk and squat scenes because no one else wanted to go there.

Before Stokes Croft filled up with hipsters and trustafarians, it was dark and threatening. At the junction of Ashley Road and Cheltenham Road sat the Full Marx radical bookshop at 110 (1976? – circa 1990), – today a Salvation Army charity shop – an abandoned shop which was squatted and then reopened as a café called the ‘Demolition Diner’ and the ‘Demolition Ballroom’, – an old VW car showroom – which had film nights, political events and live music – a little like ‘The Cube’, only dirtier and unpleasant during the early 1980’s. The riotous gigs featured such local crusty punk titans as Disorder and Lunatic Fringe. While 0.6 miles away and founded circa 1983 at 82, Colston Street, stood Greenleaf Bookshop. By the end of 2005 Greenleaf Bookshop closed after 23 years as a workers co-op, they had been battling with the ever-changing book market but finally had to stop. The co-op members were left with a business debt of around £8,000 that they were personally liable for.

Full Marx Bookshop

Full Marx Bookshop

Credit ~~ Bristol Record Office

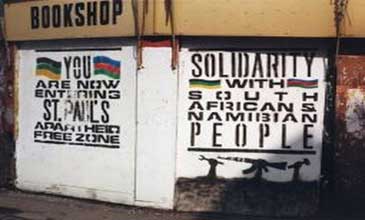

In St: Pauls during the mid-1980’s, anti-apartheid activists persuaded 21 out of 23 local shops to remove South African goods from their shelves creating an ‘Apartheid Free Zone’. The idea originated from the St: Pauls Community Association AGM in 1985 in response to the State of Emergency in South Africa. The aim was to put economic pressure on the South African Apartheid regime. Regular pickets were held outside Barclays Bank on Newfoundland Road and the campaign even persuaded the new Eastville Tesco Store to adopt an apartheid-free policy. It was the first ‘Apartheid Free Zone’ in the Country and sparked off others in Brixton and Toxteth.

Stokes Croft. 1980’s

Stokes Croft. 1980’s

Credit ~~ Bristol Anti-Apartheid

In the 1980’s a pirate radio movement emerged in the UK, prompting a new musical phenomenon that would change the face of British music. Pirate radio is often associated with the off-shore broadcasting of the 1960’s, but in the 1980’s it enjoyed a renaissance. This time stations were broadcasting music from the roofs of residential tower blocks, houses or bedrooms rather than at sea and were distinctive in the way in which they celebrated black culture. During an era defined byThatcher’s leadership, these stations offered an escape for those suffering racial discrimination and economic marginalisation. They aimed to empower musical communities reputedly ignored by the BBC and the licensed commercial stations.

Like many cities and towns across the country, Bristol had a number of pirate radio stations giving a real community voice to the Black and Asian communities from 1987 until the Independent Broadcasting Authority announced that they were to offer some smaller licences and pirates could apply as long as they closed by the end of 1988 and many pirate stations around the country decided to have a go.

‘B.A.D. Radio’ was the first West Indian / Black music pirate radio station in Bristol, running from the Summer of 1987 until 1 March 1989 when they were raided by the authorities for the second time. ‘Radio For The People’ launched on 7 February 1988 and gained an incremental licence which allowed them to broadcast to the city again on 21 April 1990. ‘Black FM’ hit the airwaves on 97.9 MHz on 21 July 1989, defining itself as being ‘. . . . NOT a community radio station but a privately owned music enterprise which likes to help out in the community.’ The station pulled the plug just before the New Year of 1991. ‘SPEC Radio’ was set up by DJ Stax and Junior Ash to try and achieve what they thought the legal version of ‘FTP’ would fail to achieve – to give a real community voice to the Black and Asian communities of Bristol, especially in the areas of St: Pauls and Easton. Broadcasting from December 1989 until 1991, having been raided a number of times by DTI officers. It returned a handful of times as ‘ReSPEC FM’. There were other stations that broadcast over the city airwaves during those years.

The summer of 2011 marked a turning point. The eviction of long-running squat Telepathic Heights sparked riots between local residents and police from Avon and Somerset Constabulary, supported by Wiltshire and Welsh police, with police occupation of the neighbourhood. Soon after, anti-squatting laws were passed by the coalition government, making it harder to open new spaces. One by one, many of the squats were emptied, with coffee shops and craft beer bars popping up in their place. In 2016 the last standing squat in the area – the Magpie – was sold for £300,000 at auction. The Magpie was one of Bristol’s oldest squats which started in 2008 on Picton Street.

Dubbed ‘Bristol’s Cultural Quarter’, Stokes Croft has a long-standing reputation for alternative living in Bristol. The pop-up culture that has been fashionable recently draws from the squatting culture but commercialises it. It used to be people with no resources making something out of nothing and now it is people with a lot more resources competing for much less space.

‘The Bristolian’ is an independent website ‘smiting the high and mighty’, exposing the council, politicians and businesspeople in Bristol, which was originally launched in 2001. In 2005 its reputation for getting scoops on municipal malpractice and provincial corruption earned ‘The Bristolian’ a runner-up prize in the Paul Foot Awards for investigative journalism. The website was relaunched in March 2013. ‘The Bristol Blogger’ ran from March 2007 until March 2012. By 2014, the UK’s journalism industry was at rock bottom. 2012’s ‘Leveson Inquiry Report’ revealed systemic, decades-long criminality by the tabloid press in order to get evermore sensational ‘scoops’ to sell newspapers. Trust in the corporate-owned press was at an all time low, at a time when newspapers really needed it – their business model was in freefall, as internet firms were scooping up the advertising revenue. Local investigative journalism was the first to take the hit and had been extinct for some time. A small group of volunteers in Bristol decided to do something about the failures of corporate-owned local media – they organised, crowdfunded and built a reader owned new-media outlet: ‘The Bristol Cable’. As a result, Bristol now has its own investigative newspaper, 100% owned by thousands of local people, free to access for all in digital and print.

Bristol Radical History Group was formed in 2006 to open up some of the ‘hidden’ history of Bristol and the West Country to public scrutiny and challenge some commonly held ideas about historical events.

At its peak, the ‘Bristol Pound’ – a form of local, complementary and / or community currency launched in Bristol, on 19 September 2012 – was the most successful ‘local’ currency in the UK. But the growth of cashless payments and cryptocurrencies eventually brought about its decline, with the challenges of the pandemic dealing the final, fatal blow in 2021. There are now only two community currencies still operating, Findhorn and Lewes. Other currencies had been set up in the Lake District (2018 – 2019), Exeter (2015 – 2018), Stroud (2009 – 2013) and Totnes (2019). The Brixton Pound is now a cryptocurrency, whereas the Kingston Pound is digital.

There are around 500 people known as Bristol Vehicle Dwellers living in vans on at least eight encampments across the city. (2021 figures). Property prices in Bristol are nine times average earnings and as people try to escape the soaring living costs by living in vehicles on the streets, they are met by opposition from residents and Bristol City Council. But, the ‘Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill’ could eliminate Bristol’s Vehicle Dwelling community.

For some, living in a van is their culture or a symbol of resistance. But for many others it is the only possible response to our growing housing crisis.

Today, the ‘cost of living crisis’ could force thousands to live in large off-grid communes in Britain.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Postscript.

Starting a new community is hard work. Even if you have a clear vision, excellent people to start it with, a place to move into and ample resources to start it, your chances of success are low. And the chances that you are starting with all these advantages is pretty low.

By the end of 2021, there were reportedly nearly 300,000 empty houses across the UK. Squatting in residential buildings (like a house or flat) is illegal. It can lead to 6 months in prison, a £5,000 fine or both. Despite this, long-term squatters who have been living in residential properties for 10 years or more can legally apply for squatters rights. The government suggests being on another person’s non-residential property without their consent is ‘not usually’ against the law.

Under the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994, property owners can legally remove squatters by applying for an Interim Possession Order (IPO). According to ‘Shelter’, this process ‘requires squatters to leave the premises within 24 hours of service’. If the squatters have not left the premises 24 hours after being served an IPO, this will be seen as a criminal offence and they could be charged by the police or sent to prison. This will also be the case if they return to the property within 12 months of leaving.

© Stewart Guy.