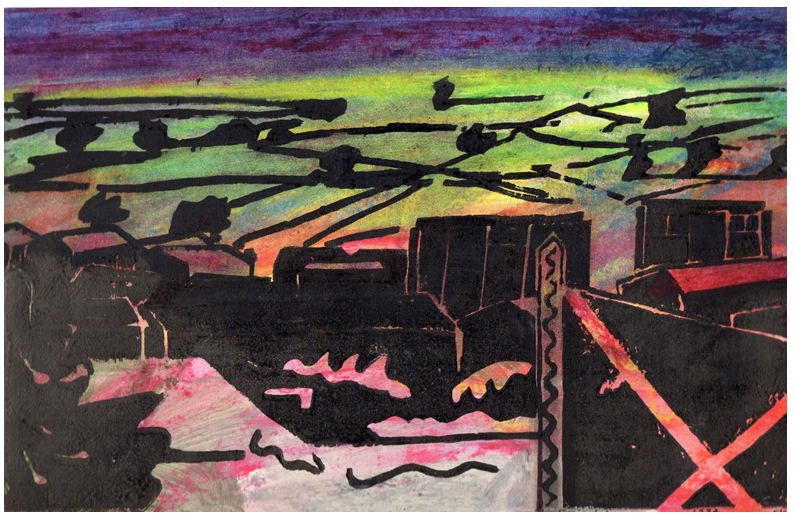

‘Estate Extent’ Linoprint on mixed media, 1984

And now it almost seems as if before

we were peacefully sleeping and then awoke

to where the months accelerated faster

dissipated the warm

and shook the distances.

Another trait supposedly descending to Volcano from Fred Optimistic, was a bodging, “Slap a coat of paint on it,” attitude. In the Grandfather’s case, quick fix or hasty solutions may have saved his life on more than one occasion. If Fred was to be believed, he’d been “Monty’s right-hand man”, through both the desert campaign and on the combat trail through Italy: although how there was ever time for battles amidst the cockroach racing and the consumption of abandoned wine, Volcano never knew. Conceivably, Fred’s ever-optimistic attitude, his air of muddling through, had been cast in reaction to the harsh historic events over which he’d driven his army truck and of which he spoke so lightly. Probably he was concealing darker memories he did not wish to dwell on. He’d always maintained that he could drive just as well or better, even when virtually unconscious or “up to the gills” in drink. As he’d been an army driving instructor when the skill was not so common, perhaps this was true. To evade possible strafing by an enemy aircraft in Italy – though having had “a skin full” – he told his pals to “load me in the seat and I’ll drive.” Had his pals regretted his assurances? Volcano didn’t know – the story was always, somehow, interrupted there.

In the eventually optimistic post-war world, up to and beyond the time of Macmillan’s famous phrase,[i] Fred must have been in his element. Renowned for restoring an old piano by simply slapping white gloss over the stained and cracked keys, (“Looks a TREAT!” he’d raptured) he’d even impressed himself! Some years later and none the more downcast, he turned up at the newly built council house that Jack in the Green’s family had been washed away from London to reach. Floating on fields circa 1966, sandy roads new-cut through the sudden verdant hope of spring (or the drifting wisps of dandelion clocks?), Fred arrived in a hand-painted blue car.

Did that car shine in sharp April sun or in a late summer dust of seeds? Newly born, its houses still shining, perhaps this was the Alderhurst Estate’s finest hour? If the house or the combined patterns of drives and closes had possessed their own collective memory, is this scene, at that phrase of time, the one it would select above all others? Would that be the best and last image it would remember? Or would it prefer itself a few years later? By then the estate – still fresh like young trees in May-time leaves – would have the beginnings of newly conjured gardens, and yet all the exiles would still be surprised by the luck of their new island.

In their curving street, Mayfair Avenue, Volcano could see in his mind’s eye, that blue car. What make it was he couldn’t say; but of Optimistic’s casual confidence there was no doubt: that car was painted with such cavalier relish that it revelled in its brush marks. In fact, it may even have still been tacky – and dashed with a sample of insects collected on the forty-mile drive from London.

In the mind’s eye it was as if all the cast of Alderhurst Estate, neighbours proud of their new found space and cheerful flowers by the red brick and white, pre-fabricated, fibre-glass panels, were standing for some extensive aerial photograph, a celebration for which they all looked upwards – each one in a family group by their house, on their island.

Presumably during construction, those forthright and conspicuous white panels (a section of both the up and downstairs façade), whose whiteness would dominate the airborne viewpoint, and which offset so well the colours of all the gathered players, had been lifted into place in one go? In all his days there, he remembered how those panels could shift in their brick guides – like a Lego house built by a child with no knowledge of stretcher or Flemish or any other bond; just built in adjoining columns, then quickly held together by jamming on the roof!

All these proud neighbours, overspill from various environs: Chiswick, Acton, Hackney and Kentish Town; Wandsworth, Peckham, the Caledonian Road . . . To Jack in the Green, all the names of London were a beautiful poem – despite that the reality of the places might struggle to reach the wrought ideal. Forget all that soft stuff about nightingales and flowers – the Estate Island generation always had the wonder of their imagined origins – so long as they did not actually go back too often.

Origins, like summer reveries or wishes, are largely imagined. We create their meaning each one of us anew, dependant on our temperament – embellishing the good, hampered by the bad. It had never been possible, despite all Volcano or Cyrian’s wanderings in real places or archives, to find any exact places or generators of this intense beauty. It was an atmosphere only. One that would suddenly pour through the fabric of reality.

He had searched and revisited diverse regions of London, hoping to find exact correlations to some dream or memory; expecting to find an actual place. But this Grail lay always just out of reach, as in the dream of Lancelot, where lain to rest in a burial ground for the night, he is paralysed but for his flowing tears, as the Grail procession passes: At the true sword’s point, found unworthy. This is a common feeling no doubt: Lucy held it for Flintshire and the foothills of the Clwyd mountains, and for some childhood memory of Offa’s Dyke. Volcano had once recollected this tale of Lancelot, paralysed by unworthiness, only to find she shared an intimacy with both the story and the emotion. She even believed there was a ruined chapel, one she’d known in Denbighshire, that corresponded: “at least in my mind.”

Everywhere and nowhere this undiscoverable region lay; it could come startlingly from a photograph or map, or from the name roundels on Tube stations: Turnham Green or Gunnersbury Park, Perivale or Headstone Lane; from a redbrick pub with exultant flower baskets: ‘The Bricklayer’s Arms’ or ‘The Crooked Billet’; from numerous scenes in films both fiction and documentary . . . fragments of evocatory power . . .

Were all such suggestions embedded in time, or could they be freed from that tyranny? How much is of them is our singular memory? Or are they generational gifts from some collective memory? How many are scenes really taken from films? The rained-off street-party at the end of ‘Passport to Pimlico’[ii] standing in for countless other celebratory equivalents, other Jubilees – even if the rain never comes.

Unlike the estate island overspill, for Londoners who’d not chosen exile, location appeared more specific. If you grew up and stayed in Kennington or Holloway, those areas, the capital’s centre and the sections between, might remain the only zones well known –the rest persisting as a whitened blank on the map. But to Volcano or Cyrian or Jack in the Green, the whole area was in the sights of his vision, out into Kent, Essex, Middlesex and Surrey. Walking through unexpected sectors, they could without warning seem about to dissolve, as if he could step through into some living past, his London, That Mighty Heart[iii], and this time he would reach his Grail, for he was part of its very blood!

Sadly, this feeling could not last . . . it would vanish, fade or be interrupted.

Alternatively, it would arise in illogical places – from an abstract painting or a country cottage. One of the strongest generators turned out to be a pub hiding down an alleyway in a West Country town[iv]: yet as well as the presence of London past, this pub in chorus sung an atmosphere of the canal. It was like a lock-keepers lodge, a tollgate on the veins from that heart. More fairly perhaps, it had a feel of the Midlands – the true heart of both canals and red brick. Impossible to pin down, the Grail always stays beyond reach – and the restlessness of the search for it, undermines all the embracing rhetoric.

But of the search one must never tire; since without such feelings our days and hours would be mostly dead. We need the embroidery of memories, of hopes and connections. Reality as an object of fact does not exist, and if we could all, as we too often do, shut ourselves down enough to achieve such a ‘reality’ (and we might inadvertently be getting closer to just that), it would not be worth having.

As a film watched in intense relaxation can become a temporary reality – so should our own complexities, from varied moments of time, create the present. An objective reality firmly embraced would be a prison – whereas the potential of each intensified moment is the beginning of true freedom. The Grail perhaps is already within us, rather than in the places and times through which we restlessly seek. The generators of beauty in an external ‘reality’, are only mirrors of our own capacity to will, and to have some indefinable faith. We need to discard time, to escape from the inadvertent life and achieve immortality – at least for now!

In a more self-conscious fantasy, all those exiles from London gathered to see Fred Optimistic’s hand-painted car: The Great-Grandad next door, (he who walked with two sticks and had figured in the First World War), who rarely spoke, but sat in an upright chair crammed into a huge buddleia bush, amongst clouds of red admirals and peacocks – he had a slight smile as if he was in paradise . . . and he was, he was! He too, hobbled out to see that blue car, alongside the burly dad from over the fence, the original motorcycle-rocker. Gestapo also – so named for his tight-lipped expression and sinister leather coat, and because the Waterboatman once caught him throwing stones at our cat – he was there and even looked happy. There was the back-garden mechanic from the house by the alley, an avid collector of axles and differentials. The two school cleaners and mothers, contrasting friends – Mrs Loud-laugh and Mrs Well-blessed, circle and stick. The deaf woman and her three voice-projecting daughters – finely adapted to the expressive screech . . .

All of them had gathered, and all the other anonymous neighbours too, to see this hand-painted car. Even Aunt Maggs, who Volcano had never seen, and who had died in the war, even she would be there. In some striving but over-golden film, a retreating climb executed by the camera would begin near the front headlight, close on those swashbuckling brush marks. Their blue would expand until the lens encompassed the fullness of the car, reversing further to capture that admiring crowd, lifting to the new houses and then sweeping up, right up, to hold the summer-misty distances where the estate island blurs into a sea of fields, its waves shown by the lines of trees and hedges that comprise the whole of the Vale of Arrowsby, stretching out from the chalk escarpment behind . . .

Some would argue that art is the one true point of civilisation; that nothing in the end counts but the alchemy that condenses and elevates reality: that it is only once reality is viewed through art, that it comes to have any meaning. In opposition, the more politically minded would say that to view art in this way, is to use it as religion was used, to use it as a drug, blinding us to poverty and injustice, stalling our care for the world – since we already believe in another.

Volcano could see shelving thoughts of value projecting from both these headlands, irrespective of their remoteness from the daily lives of many of the people on island estates such as Alderhurst. Artists were extreme and politicians rarely worth trusting. What those citizens cared for most was perhaps their underlying sense of a new frontier – regardless that it receded into the sadness of exile. For some, their new gardens were the only art that mattered. For others it was the travelling luxury they would soon be able to earn, (before it became the tired necessity of later generations): a car of their own. For such views, Volcano for one, would never blame them. He, and all his friends of the time, had held similar feelings about their bikes.

Lawrence Freiesleben, copyright 2013

Notes

[i] “Most of our people have never had it so good”. Included in a speech given at Bedford on July the 20th 1957

[ii] The famous Ealing comedy.

[iii] British Transport Film of 1962. Embedded in:

http://internationaltimes.it/devon-and-derby-an-english-journey-digression/

[iv] The Vine in Honiton, circa 1989-2005

[…] [xii] See: http://internationaltimes.it/exiles-from-london-an-extract-from-maze-end-2013/ […]

Pingback by Bomb Damage Maps – A West London Digression . . . | IT on 13 June, 2020 at 1:12 pm[…] [xxxiii] http://internationaltimes.it/exiles-from-london-an-extract-from-maze-end-2013/ […]

Pingback by The Italian Digression – Part 8 | IT on 18 July, 2020 at 6:20 am