Florence/Firenze a year on . . . drastically side-tracked by Sebald, Sutherland and San Francisco

The black and white marble immensity of Florence cathedral[i] is definitely worth more than a glance if you have an oxygen tank and can fight your way through the crowd – or wait until it rains. May 2019

Avoiding the gushing guidebook hyper-hyperbole on the one hand, and the overcast insistence of ruinance[ii] inevitably prompted by the Florence/Firenze suburbs on the other, we approached our temporary terminus with equanimity, resisting the sprinkling rain on the windows, willing the distant blue in the sky to come closer. Patience came upon me. Or am I just saying that after re-watching Grant Gee’s, Patience (After Sebald) 2012[iii], yesterday? Though ultimately very downbeat, this film with its frequently fervent contributors is densely evocative, and the more ecstatic viewer can easily choose to contradict its defeatism and melancholy[iv]; can take the black mourning ribbons off the picture frames . . .

No such ribbons decorate my memories of Florence – since something either in the spirit of the place or gifted by the passing weather, took me by surprise. Even though the city alternated extremes, its coinage came up positive in the end.

Sebald’s currency is less constructive, its east-facing foundations perhaps as vulnerable as East Anglia’s crumbling coast? Resisting the sensationalism of detailing the writer’s actual death in 2001 (and never mentioning his immediate family), the film mythologises the man, implying that rather than a sudden event, he gradually wore his life away towards the end of a walk. That he descended a ramp into some kind of burial chamber. Somehow, we feel, that he must have written the remainder of his books afterwards . . . and indeed, at 1hr 20m and 12s, proffering an elegiac, one minute’s silence, the film persuades him into a mute, smoky after-appearance[v]. A poignant coda.

Realising that Sebald was the same age when he died as I am now, and considerably less “sidelined” (to use his phrase for the unknown people he liked to talk too . . . who are most of us), my occasional hypochondriac tendencies started to give me various pains – no doubt psychosomatic equivalents to the aneurysm that prematurely caused the lifelong exile’s death in a traffic accident[vi]. Sadly, other than a few quotations, I still haven’t read The Rings of Saturn, while Austerlitz, his last book, though engaging, left no lasting impression – which could be my fault rather than his. More likely it’s due to a fundamental difference of temperament . . . though based on limited knowledge, I do have reservations not dissimilar to those advanced by Mark Fisher[vii] in his concise critique, Patience (After Sebald): under the sign of Saturn (Sight & Sound, April 2011)[viii].

How much does temperament or even humour in the medieval sense[ix] disincline us from following certain avenues of exploration? Sebald may be pessimistic, frequently exhausted and often despairing, but he generally remains lucid. Much academic writing, by contrast, is like a jungle of anaemic yet choking vegetation, a tangled maze created by its practitioners to make themselves feel special, safe and hidden from the prying curiosity of oiks. Armed with a machete, a third to a half of its wordage can often be blithely hacked away with no loss of meaning and considerable gains in clarity. Paths and even clearings open up . . . all of which sounds suspiciously like the pot calling the kettle black!

An upwardly tilted head is often the only way to free the mind from central Firenze’s pressing crowds. Palazzo Vecchio, May 2019

Despite my usual enthusiasm for 30s modernist buildings, the best that can be said of the external appearance of Firenze’s Stazione Centrale, Santa Maria Novella[x], is that it’s impressively boring. In fact, it’s almost epic in its boringness. I’m quite prepared to be shot down on this comment, for we hardly gave the place a fair chance. Between arriving there and departing three days later, we must have passed it on foot six or seven times. Despite its exterior resembling the loading bay of the least interesting of warehouses or the back of any number of contemporary out-of-town shopping complexes, it still served well as a navigation landmark to or from our rooms with two views, way out in the northern suburbs. Looking at pictures since, the interior of Florence’s busiest station appears striking. But at the time our train arrived, the concourse was too stressful and pushing to allow any decent views. Anxious to get rid of our stuff in case the skies became bluer, we had no inclination to hang about. Personally, I had a craving for a nice mug of tea, (no-one else drinks the stuff) so we headed straight for the small airbnb apartment we’d booked, the weight of the bags lightened by the fresh smell of breeze-cleaned air and the rain-washed streets.

Spiky building on the way to our apartment.

Weirdly, on the long traffic-crazed[xi] walk to get rid of our luggage, I became convinced I was in Lisbon in 1990. To this day I cannot explain why this mistaken sensation kept recurring in certain areas of north-eastern Florence. In my (limited) experience the two cities are not remotely similar visually – Lisbon being made up of hills while Florence, north of the Arno at least, is mostly flat.

Although, given the right mood, the popular 1985, Merchant Ivory production of A Room with a View (1985)[xii] can still be enjoyable to watch, it’s about as accurate to the mood of Forster’s 1908 novel as the Comic Strip’s Five Go Mad in Dorset (1982)[xiii] is to Enid Blyton. But whereas the spoof of the latter reveals some of the hideous truths behind Blyton’s largely tedious and repetitious sagas, thanks to the warmth of the settings and its entertaining caricatures, A Room with a View hides the 1980s behind its Edwardian glasshouse, fairly convincingly. If it’s upmarket trash (and it is), it’s determined to wear its most confident shoulder pads. As Lucy, Helena Bonham Carter’s hair is reminiscent of a huge unappetising cornet, while Freddie (Rupert Graves) remains in permanent, dire need of hair gel. The whole ethos of Merchant Ivory, in its audience-satisfying yearning for sumptuousness, wallows in the conspicuous greed of the Thatcherite era, in a way that perhaps (tenuous suggestion coming up) Jack Clayton’s 1974 version of The Great Gatsby, starring Robert Redford, despite similar trappings, remains cynical about such human desires for nostalgic extravagance? With almost all such films particularly from the 80s and since, no matter how good the acting is and no matter how free of undermining the script, no-one surely believes in the period setting for a second – it’s all a big charade. As much as Under the Tuscan Sun, (2003), Room with a View – at least at the time of its release – successfully camouflaged the fantasy nature of its confection. Like classical art, it hid behind an air of respectability. Looking back from 2019, its façade though superior to most period stuff made since, has clearly cracked – which doesn’t stop it being enjoyable . . . though not nearly as enjoyable (at least to me) as Checkpoint (1956)[xiv] featuring the unforgettable Stanley Baker in a small, early role as a real meanie. Filled with authentic locations from all over northern Italy, Checkpoint also highlights many of the favourite tourist spots of Florence, including the classic viewpoint of the Ponte Vecchio crossing the Arno seen from the Piazzale Michelangelo. Astonishingly, but for the volume of sightseers and the inevitable pandering to tourist money, this central area remains instantly recognisable over 63 years later.

Checkpoint (1956) also includes this definitively sexist exchange between Anthony Steel and Odile Versois (both pictured above, in a mutually friendlier scene filmed from the Piazzale Michelangelo):

Francesca: “I thought you only knew about cars.”

Bill Fraser: “And women sometimes. Anyway, they’re much the same: Tricky as the Devil and best driven fast!”

More or less the same view 63 years later – with added vegetation. 29th May 2019

In our original plan for travelling through Italy we wanted to include Naples and points south as far as Lecce and Sicily, but quickly realised that this was beyond our time and budget. Being more geographically possible, Florence was added, even though personally, I remained wary. At first it seemed as though my doubts were valid. Fortunately, a semi-visionary moment descending the parkland slope from the Piazzale Michelangelo at its eastern end, snatched victory from the jaws of defeat, and my attitude changed. Patience and an observational calmness really did come upon me. Until then, I would have written Florence off as another no-longer-real place. But once you escape from the shuffling if cheerful tourists at its centre, culture-vulture zombies seeing what they feel they ought to see, but probably have little interest in (as neither do I), there is always, in the living world of now – imbued rather than encumbered by its history, its materialist rush treated as the shallow tasteless joke it is – an unending and deep reality to be found.

Disappointingly, my semi-visionary experience was not remotely captured by any of the photographs taken at the time. I also returned for an hour alone the following day, in the same bright but clear weather and in even better mood . . . and although everything became wide and open – the city both there and not there, the ambulances dimmed – again the photos failed. Looking at them now, objectively (though I don’t believe such a thing exists, it’s a useful word) it really is just a bit of parkland with a curving downhill road, the most prominent feature of which is a crash barrier. A couple of classic Fiat 500s[xv], gleamingly restored from the late 50s or early 60s did pass uphill and later a tandem with, as usual, a larger man piloting a smaller woman – blocking her forward view. But in photographs the Genius loci[xvi] had taken indefinite leave of absence.

This area above the trees and the Arno with the city reaching out towards Fiesole and the foothills of the Apennines beyond was reminiscent at the time, of the best, most dreamlike sections of Vertigo (1958)[xvii] . . . and I had the feeling that I was trailing the essence of some higher truth in just the way that Scottie in the first third of the film, follows Madeleine through the bright-hazed flower shops, graveyards and galleries of San Francisco. Later, in more primal locations within or far from the city, they move on through their personal and darker liminal zone together. Here, Madeleine – though a fictional construct – becomes possessed by ghosts, at least in the viewers mind . . . as the viewer too becomes both the dreamer and the dreamed.

San Francisco as reconstructed by films such as Vertigo, Point Blank (1967) and Bullitt (1968), to name but a few, is a place I have always dreamed of dreaming in, though perhaps the likelihood that I’ll never get the chance to see it for real, is a good thing?

Wrong direction, but closer to the mood of Vertigo inside my head

Talking about the section above to my daughter, she suspects I’m always doing to Vertigo what Mark Fisher claims of Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn: “my suspicion is that misremembering of a different kind contributes to the Rings of Saturn cult. The book induces its readers to hallucinate a text that is not there, but which meets their desires”[xviii]. Yet if it’s true that both The Rings of Saturn and Vertigo have the power to be all kinds of things to all kinds of people, to suggest what they don’t contain, then perhaps it indicates the quality of both? Since this is precisely what I am always saying the best art should do. To breathe the truth we cannot sustain . . .

If the centre of Rome seemed small, at less than a fifteenth of London’s size[xix] Florence is ideal for walking – provided you can force your way through the central press. Beyond this, the crowds suddenly died away – often to nothing in areas even more interesting. The surviving city walls south of the Arno appeared from high up, like a renaissance painting, the countryside seemingly rambling right up to and into the city.

Evenings found us stranded in the northern reaches of the city, K or I having to be around while the children tried to sleep. Apart from the annoying sound of ambulances – constant in every city, though at least the Italian ones have older style sirens – the apartment was fairly quiet. As Firenze “has the highest life expectancy of any city in Italy” I can only assume that people phone for an ambulance every time they stub a toe? Inevitably the usual magazines adorned the apartment, but the cultural variety here aimed higher than those I’d idly perused in Perugia . . . only emphasising how far the world of art has long lost its way. Of course, there are many individual exceptions, but as a unified driving force, did art die even longer ago than proper cars and trains? At the Uffizi Gallery and Pitti Palace, one local magazine touted Tony Crag and Kiki Smith – artists too middling to be worth export. But then who, of the random selection of contemporary artists nationally prominent nowadays, are worth domestic interest, let alone export? The art world depresses me almost as much as the persistence of tory governments[xx].

Here, I was going to counter the criticisms of Graham Sutherland made by Laura Cumming in a nine-year-old Guardian review[xxi] I chanced upon that first stranded evening in Florence. Although, in the sneering spirit of Henry Moore[xxii], she digs up the old Sutherland/Bacon comparison[xxiii], predictably concluding that: “Bacon’s powers exceed those of Sutherland by some way,” her review is basically deeply felt and positive. Being stuck indoors must have exacerbated my overwound state – though certainly she is wrong that “Sutherland seems to be always aiming for a darkness of vision he never quite reaches.” On the contrary, perceived correctly, Sutherland is trying to escape a metaphysical darkness rather than wallow in the sordidly human one explored (equally searchingly at times) by much of Bacon’s work. But to be fair to Cumming, perhaps the exhibition didn’t include Sutherland’s better oils?

Her other muddled comments stem from a misunderstanding of the aims and ‘uses’ of abstract art and are not worth getting into[xxiv]. More important is to trace why her misapprehensions irritated me so much – and thanks to some garbled notes, written out of sorts, stuck indoors in the prison of time, the mood begins to come back:

“The past is not dead, it’s not even past” said Faulkner and now I’m in a traditional, narrow-minded agony of the past. Of my intense identification with Sutherland in 1979 and 1980. With the 30s to the 50s and those landscapes. With Kent and Pembrokeshire. How close we came to La Villa Blanche in Menton, on one of our typical back roads from Nice to Genova. D24 Route de Castellar. That would have been a worthy pilgrimage. 50s & 60s photographs, made it look wild and remote – like one of his knotted pre-war Welsh landscapes with added rocky peaks[xxv]. Now, more clearly, it’s obviously situated in a Riviera suburbia[xxvi]. Yet my traditional imprisonment is also due to places gone or spoilt[xxvii] – of the “exultant strangeness”[xxviii] of Pembrokeshire as it was back then, before tourism really got going. But it’s also for a desolate sense of my own past – its dreams, intensities and failures. What eventually broke me out of this caging mood was encountering on the internet Blue Cross Fold, Carbonell[xxix] and Cocktree Throat[xxx]. . . which together, countering the spirit of ruinance, gave me the foolish sensation that they back me up. That they will take over where I must leave off. The internet is so good at creating a (totally false) sense of not being sidelined.

The following day, walking a different route into the city, we improvised a long triangular route whose first landmark was the Streamline Moderne, Teatro Puccini (above). Built in 1933 but not opened until 1940 this has served as cinema, dance hall and host to boxing matches, before becoming a theatre in the 1990s. Choosing the left-forking direction, just along the road, comes the equally distinctive cigarette factory or Manifattura Tabacchi, built in the same period and for which the City has such ambitious plans[xxxi].

Under a tortuously skewed railway bridge we continued past the Visarno Arena, a horse racing track which also hosts concerts and whatever else is necessary to stay afloat. Entering the peaceful Parco delle Cascine and following the high flowing Arno, eventually we had to run the gauntlet of a traffic-heavy ring-road. Here, one-way, multi-lane tides are divided by terraces and buildings just as bridge piers split the heavy currents of rivers. Narrow balconies and washing nevertheless hangs above the flood of car fumes, like morose bunting, hangs right above the street – a world very different from the one I’d inhabited in the half-light early that morning:

The magical road you are on, begin my notes, but this positive gesture goes nowhere. Followed up George Shaw[xxxii] this morning, (never heard of him till yesterday) – a few of the housing estate paintings are (superficially) intriguing but soon wear off. To what extent is art, writing etc, a defence against reality? Obvious really. George Shaw occasionally idealising the estate of his youth – which is how it appears in retrospect – in contrast to his “miserabilist” present, the grey reality. Though I’m wholly aware that when I recast the Elmhurst Housing Estate (circa 1966-72 or so) in the light of Eden[xxxiii] it’s a deliberate fictionalisation.

Through the San Frediano (supposedly the “coolest neighborhood in the world”[xxxiv]) and Borgo Santo Spirito areas of Florence, we were edging back towards the known city, dithering before taking the decision to veer further away.

Crisscrossing the obscure backstreets of the Isolotto-Legnaia (Quartier 4) district, the garage above was reminiscent in smell and atmosphere, of an artist’s studio – a reality so distant from the removed spectator sport of casual bourgeois criticism. Off to the right on an ancient calendar, like a kind of go-between betwixt mechanics and art, a nude offered a prayer to a Vespa[xxxv] – not quite an image the Renaissance would have had in mind:

Further on, higher up and edging into posher architecture, came a second variety of mediator or strange compromise – this imposing Florentine, 3-wheeler truck or lorry, blocking the street almost entirely:

Another common complaint voiced in the Sutherland versus Bacon debate is that Sutherland failed to evolve. In truth, neither Bacon nor Sutherland developed their technique excessively. Why should this matter? Can’t you have obsessive explorers as well as restless experimenters? Far too much ‘evolution’ is forced by the pressures of commerce or fashion, a skin-deep value that soon crumbles. While second rate artists find (or fail to find) an apparently original style or formula and stick to it, copying themselves, only thinking about making a living, the best – successful or not – work for themselves or for some stranger, indefinable reason. None should be required to change. Depth isn’t about change. Real artists aren’t playing at art school anymore (if they ever did). If you are obsessed with some meaning behind, why should you care overmuch about the surface? Inner content is what counts. Determined and resolute, Sutherland and Bacon were both stuck in either a dream or a nightmare according to the taste of the spectator – “as with the taste of bittersweet fruit” to use a phrase of Sutherland’s. Neither of them could escape. Both remained prisoners of their neurosis and fears.

With the Arno so high, it was natural to remember the disastrous floods of 1966[xxxvi] and the documentary, I’ve read about but never seen, Per Firenze[xxxvii] directed by Franco Zeffirelli. Passing through Piazza Santa Croce early in the morning before the crowds have had a chance to gather, I’d noticed the flood marker[xxxviii] commemorating the square’s submersion under twenty feet of water.

If it’s occasionally true that the work of artists springs from personal defence, the important evolution in art is to transcend the visible, everyday world. Breaking the artist out of their prison, ideally this should have the same effect upon any enlightened spectator who cares to look deeply enough. The best art is not about aesthetics, style or gestures and certainly isn’t about reproducing a likeness. Either, it should embody transcendence or if that doesn’t appeal to your make up, your temperament, your humour, it should be questioning or eloquent about, pain, resilience or defiance. But to be uplifting as well, it must sing beyond human limitation. Without such “romantic twaddle” I wouldn’t bother at all. George Shaw, Bacon and Sutherland may have no choice but to accept their temperamental limitations in a way that less bound artists refuse to?

Astonished to discover that admission was free – a generosity rare in both city and country –we ascended through the Giardino delle Rose (above), to return to the Piazzale Michelangelo. Basically, a big car park with occasional market stalls along one edge, it’s well worth visiting for the panoramic views. Our youngest daughter is especially keen on old artists with beards – Michelangelo to her is a Mediterranean Santa – and she was very disappointed that he wasn’t to be found in his square in person, painting and lavishly handing out the results, even though she’d now bothered to make the climb twice.

Half an hour later in a more hidden place, thanks to the arrangement of trees and flowering shrubs and the variegated sunny views of Florence through leaves beyond the crash barrier, effortlessly I was transported the 6100 miles between Florence and the San Francisco of Vertigo. “Why, whenever you are anywhere good, do you always want to be somewhere else?” K often asks. But I never see it that way. In an ascending frame of mind, it isn’t a question of favouritism or dissatisfaction, different places and times link quite naturally.

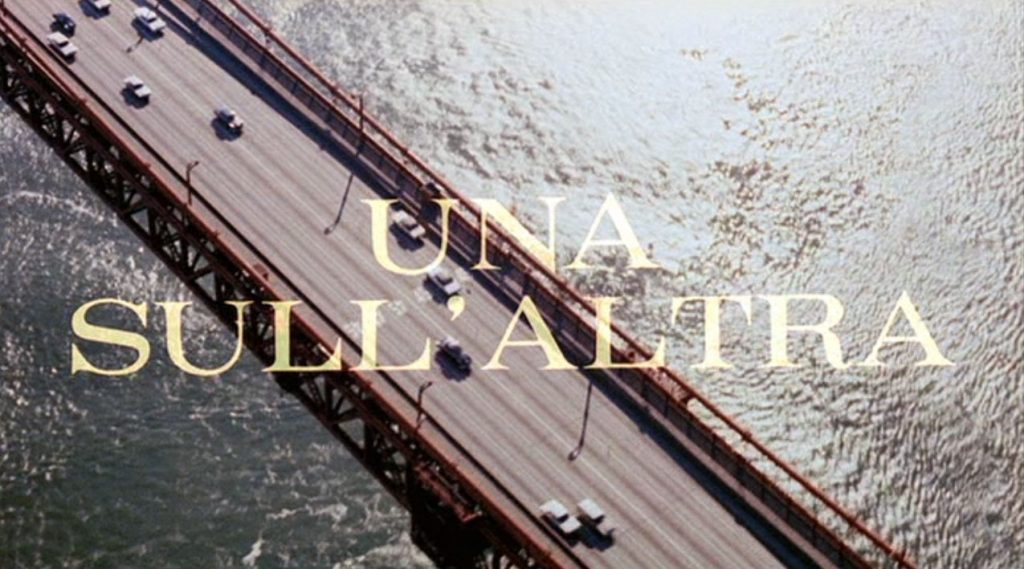

Another film that does justice in location terms[xxxix] to San Francisco is Una sull’altra, also known as One on Top of the Other (1969)[xl] or Perversion Story. Though it gets bogged down occasionally in overlong sex and night-club scenes, it does star the iconic Marisa Mell and the subtle Jean Sorel – a French actor who spent half his life in frequently memorable Italian films[xli]. I used to find Sorel bland, the deliberate blank he depicts in Buñuel’s Belle de Jour[xlii], but at some point, he inexplicably grew on me.

Only inferior art is entirely ‘of its time’. The best art, music, film, literature however, is capable both of embodying its time and yet also later, escaping it. No matter how tired certain examples may become through over-exposure (everyone neglecting to look past the frame), being twenty or two-hundred years old, does not diminish their value. Such work is rare, but the best of Sutherland’s Neo-Romantic landscapes both embody and escape their time. Forget the fashions and the hidden rivalries. Treat with caution the views of renowned or dominant critics. The supposed objective structure even of known history itself, is only a very dodgy skeleton. Change the angle of viewing or the method or viewpoint of interpretation, and the history changes with dexterity. That increasing amounts of it can be recorded these days, won’t necessarily make it more truthful.

If you can take its over the top, operatic tone, siren-sang or pile-driven by another of Bernard Herrmann’s defining scores, Brian De Palma and Paul Schrader’s worthy homage to Vertigo and Hitchcock generally, is actually better than quite a few of the Master of Suspense’s later efforts. Sharing the cinematic haze and dreaming tone of Hitchcock’s San Francisco-set masterpiece, De Palma’s Obsession (1976), shifts another older man’s stalking sessions to a wintry Florence – to include distant views from the Piazzale Michelangelo.

Meanwhile, I realise that my atmospheric connection to the idea of San Francisco started back in the sea-fogs of time and from many overlooked directions. It pre-dated my appreciation of Vertigo by twenty years. The summer sun may not have (faintly) permeated this mystery until elements of the late 60s West Coast Sound (the phrase seems to mean virtually anything to the internet) filtered through. Reluctant about the enthusiasm my dad and uncle had for The Beach Boys, it perhaps solidified when I was briefly living above Tantadlin, an early organic food outlet in Aylesbury, run by pragmatic hippies and alternatives. I was fifteen and painting a mural for a friend who worked in the shop and had one of the rooms above[xliii]. The mural was derivative of a Rousseau jungle, and the summer 1978 weather outside was suitably humidified by rain from the Woodstock festival of 1969[xliv] – courtesy of one of my friend’s LPs which I played relentlessly, especially side 3, featuring alongside Joan Baez and Melanie, David Crosby’s ever-haunting ‘Guinnevere’[xlv]. Whether it breathes from Devon, Morecambe or California, I can still visualise Crosby’s open-topped drives and feel that “warm wind down by the bay” – linked as it is to something indefinable.

Container of the Past, May 2019, at Florence or Firenze – whichever you prefer.

Art goes in cycles – there is no significant method that has not been used or attempted, every flat field or scumble, every flick, flap and gesture: on one scale or another they will be there somewhere before – if not necessarily recorded, easy or even possible to find. Some of Constable’s sketches for example, are not unlike paintings by Jack B. Yeats – but being a hundred years too early could not be accepted as ‘finished’ even by Constable. None of this matters. If art often appears to be of, ahead, or behind its time – it’s because the time makes the boxes and chooses the scale.

Nowadays (and this could be a good thing, as the internet could potentially be a good thing) there are no boxes – or rather perhaps, there are thousands of smaller boxes? Hence seen from one point of view, you have the postmodern free for all, the relativist scrabble and gimmick pointlessness . . . which could be seen positively instead – great, if you can manage it – as a wonderful melting pot, with no dictated style succeeding or suppressing another. But don’t mistake the confluence of all these cycles for some rationalist progress, ever moving onward. It’s still part of a cycle. It’s just that now all the cycles are running at once and few have the confidence to separate the treasure from the gild or the dust . . .

© Lawrence Freiesleben,

Florence & Cumbria, 2019 – July 2020

NOTES

[i] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florence_Cathedral if you are interested in all that sort of stuff

[ii] I (probably wrongly) understand Heidegger’s ruinance as an agnostic version of the Fall in the sense both of a loss of innocence, and also of a requirement to recognise an awareness of potentially never-ending emptiness – which is how, negatively, we have little choice but to view a world where we can never truly finish anything and where all accomplishment is temporary. Rather than submit to pessimism however, I view the magnetic vacuum of ruinance as a call to arms. Subject to mood, the most desolate areas of cities embody ruinance for me, whereas (to oversimplify), lush, fertile landscapes might represent the opposite. Arguably however, ‘beautiful’ landscapes can make us complacent, whereas moors, parks and suburbs, in their very different ways, create a contradictory energy. Meanwhile, landscapes of the sublime, boost the overwhelm.

Two more thorough definitions of ruinance:

From: Thinking in Ruins: Life, Death, and Destruction in Heidegger’s Early Writings by Has Ruin: https://www.academia.edu/36952379/Thinking_in_Ruins_Life_Death_and_Destruction_in_Heidegger_s_Early_Writings

From: Heidegger and the Problem of Consciousness by Nancy J. Holland:

[iii] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2118702/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_5

[iv] History – as Sebald, verbalized by Jonathan Pryce – carelessly writes at the end of The Rings of Saturn, is no more “a long account of calamities”, than it is a record of triumphs. Though I’m not immune from the effectiveness of either quiet rhetorical assertion or sound and fury which ultimately signifies nothing, patently sweeping statements made for effect, can, when thought about later, be annoying. Adam Phillips in the course of Patience (After Sebald) claims “that only children have homes. That adults don’t have homes”. This statement – with which he is sure Sebald would have concurred – may be temporarily haunting but is plainly nonsense. Some of us can feel at home in a week. I never had a sense of home as a child but find such a feeling almost all too easy now. Obviously in the metaphysical sense there are only transient homes on earth, but that is not what his mawkish statement is about. It’s not about the anxiety of non-belonging and potential nothingness, rather, for the sake of the film, Phillips is trading on a nostalgia for lost childhood. So, although I don’t believe in any ultimate objectivity, and remain certain that science is only capable of exploring a surface (even the matter under the surface is part of the surface); although, I believe, to paraphrase Nancy J Holland on Heidegger (ibid) https://blackwells.co.uk/bookshop/product/9780253035943?gC=5a105e8b&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIxePA3KSv6gIVV-7tCh3UJgmZEAQYAiABEgKEP_D_BwE that “our knowledge of the world is built not from the outside in, through perception, but from the inside out”, I still occasionally find such wooly statements unhelpful . . . despite that I am prone to making them myself.

[v] Courtesy of a firework let off by artist Jeremy Millar – a still photograph of whose smoke dissolves into and out of a photograph of the reluctantly famous author. The tribute of silence is relieved by birdsong towards the end. Arguably, like a horoscope, the smoke could have been made to fit many images . . . which obvious fact doesn’t undermine either the moment’s uncanny power or its sincere eulogy.

[vi] Or so the coroner concluded: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._G._Sebald

[vii] Following his tragically premature death by suicide, Fisher has become as ‘cultenized’ as Sebald.

[viii] Unlike my crumpled print pages saved from the magazine, this article is available to read without fold lines: https://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/features/patience-after-sebald-under-sign-saturn

[ix] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Four_temperaments

[x] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Firenze_Santa_Maria_Novella_railway_station

[xi] From an email reflecting on our Italian trip a month later: “The trouble with Europe is all the effing cars are the same, the clothes, the shops etc. Went to Tunisia when I was a kid and that was very memorable – but I expect they all have cr*p modern cars now and supermarkets. Bring back camels and flying carpets!”

[xii] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0091867/

[xiii] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0544869/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1

[xiv] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0049065/?ref_=nv_sr_4?ref_=nv_sr_4

[xv][xv] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fiat_500

[xvi] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genius_loci

[xvii] Hitchcock can be a great director, but like the very best paintings (and I don’t mean those for which Florence is famous), Vertigo is beyond design.

[xviii] Ibid: Mark Fisher on Grant Gee’s Patience (After Sebald).

[xix] London is 1,572km2 while Florence is only 102km2

[xx] Rewatching Patrick Keiller’s very special film, London (1994), recently, I was depressed that his narrator made this observation after the 1992 election: “It seemed there was no longer anything a Conservative government could do to cause it to be voted out of office. We were living in a one-party state.” Talk about inevitable ruinance!

[xxi] https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/dec/18/graham-sutherland-unfinished-world-review

[xxii] Mentioned in Part 6 of this digression: http://internationaltimes.it/the-italian-digression-part-6/

[xxiii] From Part 1 of this digression: “but in the critic-fanned rivalry between Sutherland and Francis Bacon, the latter was bound to triumph: his often brilliant work – morbid, sordid and dangerous to know – is far more suited to the modern decline.” See: http://internationaltimes.it/the-italian-digression-part-1/

[xxiv] Sutherland’s work always remained rooted in reality and perhaps it’s a moot point that his work was limited by his skill as an etcher and draughtsman – just as some highly skilled musicians cannot break their habitual strictures and improvise. But most effective examples of war/anti-war art, have no option but (to paraphrase Cumming’s implied criticism) cede idiom to reality, with Guernica as perhaps the obvious (but only partial) exception. Beyond a certain point in war and propaganda, modernism was just not suitable. The best abstract art attempts to suggest better worlds, it is not interested in the historical, political mess of this one. Hence photography is better at depicting the horrors of war. When you are dealing with a harsh reality, the shards and planes of cubism are apt to look jokey or like some driveller in their ivory tower. Even Picasso could not repeat the effectiveness of Guernica

[xxv] This is how Robert Wraight described it in the Studio magazine of August 1962: “From Menton the Route de Castellar snakes up the Alpes Maritimes offering a new impressive vista of craggy mountains at every bend. About two kilometers out of the town La Villa Blanche, Sutherland’s home and workplace for half the year, clings to the hillside between wild, wooded heights and looks down upon the sea several hundred feet below. Designed by a woman architect” [Eileen Gray, see: https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/art-and-design/bringing-eileen-gray-into-the-light-1.1314584 ] “who claims to have influenced Le Corbusier, the villa is known to the villagers of nearby Castellar as ‘the house that looks like a boat’ because its luxuriant garden is straddled by a series of elevated gangways that facilitate the climb up and down its steep incline.”

41 years later, this is from the Guardian of 2003: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2003/feb/23/shopping.homes1

[xxvi] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Quartier_de_Bellevesasses.jpg

[xxvii] Including Picton Castle’s gallery of paintings donated by Sutherland in the 70s. Although the gallery still supports local artists, the shifting of Sutherland’s work back to Cardiff in 1995 was a travesty. A typical result of the centralisation we should be dismantling.

[xxviii] Graham Sutherland writing in Horizon in 1942

[xxix] https://atelierthink.co.uk/Carbonell

[xxx] https://atelierthink.co.uk/epages/33c9cf08-cc81-49e7-b81c-6947a13df200.sf/en_GB/?ObjectPath=/Shops/33c9cf08-cc81-49e7-b81c-6947a13df200/Products/404

[xxxi] One of the old magazines in our apartment: http://www.theflorentine.net/news/2018/04/florence-manifattura-tabacchi/

2020 Update: https://magazine.salonemilano.it/en/around-design/florences-tobacco-factory-takes-on-a-new-lease-of-life

[xxxii] http://www.artnet.com/artists/george-shaw-2/

[xxxiii] http://internationaltimes.it/exiles-from-london-an-extract-from-maze-end-2013/

[xxxiv] https://www.tornabuoni1.com/en/2018/02/16/san-frediano-coolest-neighborhood/

[xxxv] Though I can’t be sure it was a Vespa: http://internationaltimes.it/axe-the-china/

[xxxvi] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1966_flood_of_the_Arno

[xxxvii] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0193404/?ref_=nm_flmg_dr_25

[xxxviii] https://www.tuscanysweetlife.com/en/florence-flood-1966/

[xxxix] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0065148/locations?ref_=tt_dt_dt

[xl] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One_on_Top_of_the_Other

[xli] To give but four examples: I Dolci Inganni (1960, with Catherine Spaak), La Giornata Balorda (1960), Vaghe Stelle dell’Orsa… (1965, with Claudia Cardinale), The Short Night of Glass Dolls (1971, with Ingrid Thulin).

[xlii] https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0061395/?ref_=nm_flmg_act_67

[xliii] In the evening he used Tantadlin’s scales to weigh cannabis resin – red, gold or black at the time. Though I never had the money for such luxuries, my friend was occasionally generous with “offcuts”. Not that any kind of drugs are of much interest to me, I prefer to believe in the imagination itself.

[…] [xxxviii] See: http://internationaltimes.it/the-italian-digression-part-8/ […]

Pingback by The Isle of Portland Digression | IT on 12 September, 2020 at 6:12 am