By Leon Horton

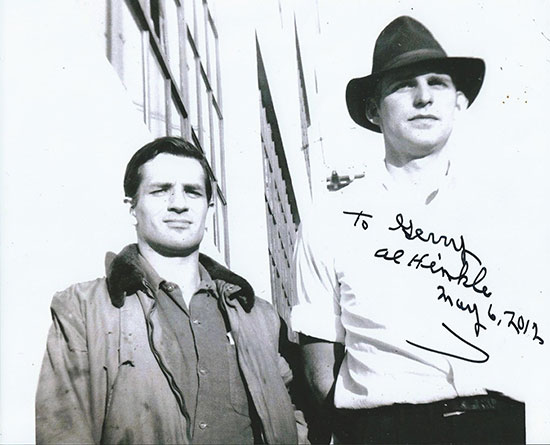

Jack Kerouac with Al Hinkle, San Francisco, 1952. Photo courtesy of Gerald Nicosia.

You would have to be dead or in a coma to have missed the fact that March 12, 2022, marked the centenary of the birth of writer and lonesome traveller Jack Kerouac, author of On the Road. To mark the occasion, Leon Horton talks to the writer and scholar Gerald Nicosia, author of Kerouac: The Last Quarter Century, Beat Scrapbook, and the sublime and authoritative Memory Babe: A Critical Biography of Jack Kerouac, widely regarded as the definitive Kerouac biography.

Hello, Gerry. With the centennial of Jack’s birth and your biography Memory Babe to be re-released in September, you must be extraordinarily busy at the moment. How are you?

I’m worse than “extraordinarily busy.” I’m going through a divorce and have to move out of the home where I’ve lived for 30 years. I have literally tons of books and papers to pack up. And yes, I’m handling the publication of the new Memory Babe at the same time.

Have you been involved with any of the great many Kerouac celebrations that have taken place this month?

No, thanks to the ongoing blacklist of my work by the Sampas family, who control the Kerouac Estate thanks to a Will that was proved in court to be forged (but which they kept because of a statute of limitations), I was not invited to a single Kerouac celebration.

You studied English and American Literature at the University of Illinois, but when and how did you first become aware of the works of Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation?

When I was a graduate student at the U of I, I was a teaching assistant to help pay my way. Kerouac was not taught in any classes there, nor was he taught in any college in the U.S. at that time. But I shared an office with a fellow T.A., a hip Jewish kid who had gone to Harvard, who was forever taunting me about not having read Kerouac. So one day, to shut him up, I picked up The Dharma Bums, and I was converted from that moment on. Despite having read dozens of contemporary American novelists in my classes – Updike, Mailer, Roth, Bellow, et al – I had never encountered one who asked “the big questions,” as Kerouac did from the first few pages of The Dharma Bums: Who am I? Why am I here on earth? Who put the stars up in the sky?

It concerns me, what with the outbreak of “cancel culture” and both ends of the political spectrum seemingly unable or unwilling to contextualize works of art and literature, that many of the Beats will be sidelined or completely written out from future discourse on what constitutes great writing. The Beats have always had their defenders and detractors, but have you seen this happening at all?

Well the Beats were cancelled early on. They were called “sponsors of juvenile delinquency,” “black spots on America,” and so forth. Their story is a story of coming back, refusing to be buried, and reappearing in every successive generation. I don’t worry about “cancel culture” because the Beats have proved already that they can’t be cancelled. They are among the few writers in America’s three centuries of literary history who actually tell the truth; and people, especially young people, will always be hungry for the truth – Vladimir Putin notwithstanding.

Kerouac’s star has risen, dipped, and risen again quite a few times since his death in 1969. There was a great resurgence here in the UK in the early 90s, when many of his books were republished and found a new generation of readers, including myself. How do you think his reception has changed over the years?

Here in the U.S. it’s been a steady upswing in recognition. In the 1980’s we had major conferences, including the Naropa Institute’s 25-year-anniversary-of-On the Road celebration in 1982 and the dedication of the Commemorative in Lowell in 1988. In the 1990’s we saw the re-issue of his spoken-word albums and the publication of many out-of-print and never-published works. In this new century there has been a wealth of new critical writing about him. There is still a backlash of moral criticism that sees Kerouac as Norman Podhoretz did, as a destructive influence on American society, but those voices are growing steadily dimmer. I think you would find few American English departments now who would refuse to acknowledge Kerouac as one of the top American novelists of the 20th century – in the lineage from Dreiser to Hemingway and Fitzgerald, to Steinbeck, Vonnegut, Baldwin, Styron, Richard Wright, and a few others who have tackled the really big issues of American society.

He was a prolific writer by any standards – between 1946 and 1969 he wrote 20 novels and 12 books of poetry – and yet he was often wrongly described as an overnight success after the publication of On the Road in 1957. It is nonsense, of course, we all know “overnight success” takes years – but did his writing become a way of escaping from the responsibilities and stresses of being a published author?

I really don’t understand your question. Kerouac was dedicated to writing and telling the truth. After On the Road was rejected, multiple times, he took what was essentially a religious vow of poverty.He vowed to himself that he would keep writing the truth, in the most radical way that he could (pushing farther and farther into post-modernist subjectivity, tracing the actual workings of the mind), no matter if anyone understood him or published him, no matter if he never made another dollar at it. Having his radically innovative works published began to seem an impossibility to him, so he assumed he’d have to go on working rough jobs like seaman and brakeman on the railroad in order to survive, or living as just a bum or hobo. In this he had the model of some other American writers, such as Whitman and Jack London.

Kerouac described the major body of his work, books of prose and poetry, under the overarching Proustian title The Dulouz Legend. Each book can be read independently, but to the uninitiated, which three books – we’ll take On the Road as a given – which three would you recommend they start with and why?

The Dharma Bums is probably the easiest to understand, a kind of update of Jack London’s style, and it is also one of the first attempts to see America through spiritual eyes, see America as a spiritual questing-place. But I have to also recommend they read Kerouac’s three greatest books: Visions of Cody, Doctor Sax, and Desolation Angels. In my new Memory Babe, I call Visions of Cody the first postmodern novel – because Kerouac is now approaching “reality” as a mind-construct. In 1952, no other writer had yet done this, and now, of course, exploring the subjectivity of consciousness is the main thrust of modern writing. Doctor Sax is also a pioneering postmodern novel, because Kerouac attempts to merge fantasy and reality, which is much like Latin American “magical realism.” And Desolation Angels is a great novel because it portrays a vast swath of America, from the fire-lookout mountains of Washington State to the coffee house/poetry culture of San Francisco to the sophisticated world of New York. All of America in the 1950’s is in that book, and no-one else did such a thing. And don’t leave out Jack’s poetry. Mexico City Blues influenced a whole generation of poets – was a major influence on Ginsberg, Michael McClure, Robert Creeley, Gregory Corso, and so many others. Kerouac was creating a new kind of poetry where everything, from the real world to the writer’s random thoughts, could blend together in a musical mixture easy to read, fun to read in its rhythmic musical choruses.

His poetry – Mexico City Blues, Scattered Poems, Old Angel Midnight – he’s in there with some greats: Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti …To use a mixed metaphor, he was batting alongside some heavyweights. As a poet yourself, do you rate his poetry? Do you think it stands with the best of his work?

Oh yes, his poetry was a watershed. It was landmark work that influenced the whole flow of modern American poetry. It’s hard to find a major poet of Kerouac’s generation that wasn’t influenced in some way by him. The amazing openness of the writing, the ability to let in so many different aspects of consciousness, while still tying it to a personal identity, completely changed the conceptions of American poetry, and left academic poetry back in the dust. Even those who didn’t openly acknowledge him, say Robert Lowell or John Berryman, began writing much more personal poetry after Kerouac and the Beats hit the nation like their own kind of atom bomb.

There have been numerous attempts to bring Jack’s books to the big screen, starting with the lamentable The Subterraneans in 1960. It seems quite logical, given that he saw his writing as “book movies”, but so far the results have mostly been unimpressive. Why has it proven so difficult to translate Kerouac to celluloid?

Because the filmmakers who have taken him up seized him for the wrong reasons –because they thought he was hot or sensational property. They did not see him as a psychological or spiritual novelist, which he was. Can you imagine The Subterraneans as made by John Cassavetes? Cassavetes, who had so much more of a deep appreciation of personal idiosyncracy, personal crises, could have done Kerouac justice. I’m not sure what filmmaker today is up to doing Kerouac, but I’d like to see Jim Jarmusch take a crack at it.

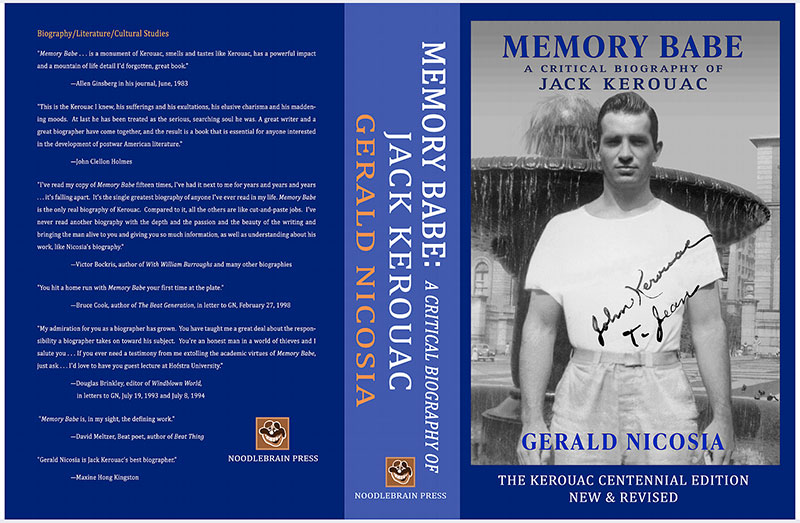

Your biography Memory Babe has been out of print for 20 years but thankfully an expanded centennial edition will be released in July. Described by William Burroughs as “by far the best of the many books published about Jack’s life and work,” Memory Babe earned the Distinguished Young Writer Award from the National Society of Arts and Letters when it was first published in 1983 – a truly incredible yet much deserved accolade. How long did the original take to research and write?

Six years. Two years researching – 50,000 miles and 300 interviews – two years writing – and two years wrestling with publishers to see it done correctly.

What can we expect from the new edition?

A lot of new materials about different areas of his life, a lot of new photos. I deal with the discovery of the Joan Anderson Letter, the truths we have learned about his ancestry, his last years, and his estate, and a lot more.

You once described yourself as “raised poor – an Italian Catholic outsider in my own way”. When you were researching Jack’s working-class childhood in Lowell, Massachusetts, did you find yourself relating to your own background in Chicago?

Yes, I identified with Jack in many different ways. One shrink thought there might have been too much “transference” going on; but another shrink said the positive transference pushed the biography into interesting areas where it otherwise might not have gone.

Did your view of Jack change during the research and writing? Assuming you had any – I promise you, I’m not – did you find you had to rethink your own presumptions and prejudices as you unearthed more material about Jack’s life?

I knew from the start that he was a self-destructive alcoholic, but I found that he was far more deeply troubled, psychologically disturbed, than I had ever imagined. He had real troubles relating as a human being among other human beings, and certainly as a man relating to women. Art, writing, was a safe haven for him from the real world, and that was one of the reasons he poured so much energy into it. I started out admiring him enormously, but in the end felt really sorry for him, for the enormous pain he endured just living from day to day.

Jack’s friendship with Neal Cassady has been well documented through his writing and in numerous essays and biographies. I think it is fairly well known – something, correct me if I’m wrong, that Jack himself complained about – that people often confused him with freewheeling Cassady (or his alter ego Dean Moriarty in On the Road). Was that part of the reason their relationship waned?

No, their relationship waned because they were really very different sorts of men. They were tied together by women they both loved, like Luanne Henderson and Carolyn Cassady. I talk about this in my earlier book One and Only. Cassady was a man who was always out to have a good time, he was an incredibly physical man, and Kerouac was most comfortable when he was living in his head. The real world scared him in a lot of ways. The way Cassady tore recklessly through the real world fascinated Jack on an intellectual level, but when Jack had to live it with him it scared the hell out of him.

Much has been made of Jack’s complicated relationships with women – most especially with his mother Gabrielle and his three wives – often discussed and usually dismissed as misogynist. Was he a misogynist? It seems a little unfair to single him out, especially from the other Beats, when they were all living through times where women were often bound by the strictures of a staid and patriarchal society.

He feared women and the demands they put on him. Women were constantly forcing him to live in the real world, to meet obligations, and as I told you, the real world was a scary place for Jack.

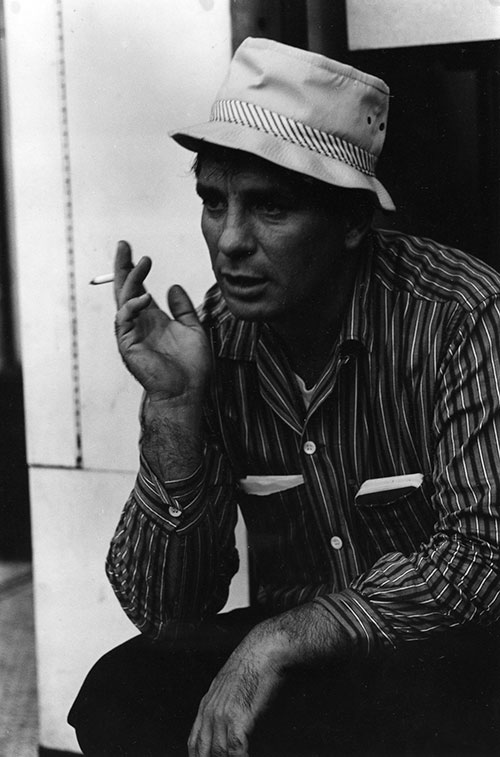

Jack Kerouac in Italy, 1966. Photo courtesy of Jon Collins

People often think of Jack as being the life and soul of the party when he was taking “a slug from the jug” but he was actually a very shy man, not effusive at all. Was he an intrinsically lonely man, do you think? Loneliness, after all, is a crowded room.

I don’t think Jack was lonely. He was easily bored, might have had ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder), which wasn’t diagnosed much, if at all, in those days. He had to have an endless stream of excitement in his life; but he couldn’t deal with that excitement unless he was anesthetized with booze. A bad formula, one destined to kill him young.

Jack Kerouac at corner of Columbus Avenue and Broadway, North Beach, San Francisco, 1960. Photo by James Oliver Mitchell.

It was the booze, of course, which destroyed him in the end, not helped by his overbearing mother Gabrielle. I don’t think we should seek to make excuses for his alcoholism – it is what it is – but do you think it was exacerbated by his family?

His sister and cousins can’t be faulted for thinking he should have gotten a regular job and supported himself. But his mother was enormously controlling of him, didn’t want to let him go. At the same time, she put unreasonable expectations on him, wanted him to be the “saint” that had been lost when her other son Gerard had died. The pressure from his mother was certainly part of his becoming an alcoholic; but as I said earlier, he had a very hard time dealing with the pressures and experiences of ordinary life. The fact of death, which he experienced very young, was always hugely traumatic for him.

Since we are on the subject of families, we must talk about the Sampas family, Jack’s final family, as it were, through his marriage to Stella Sampas. I’ve read some terrible things: the forged Will, their attempts to blackball you, selling Jack’s belongings piecemeal to private collectors – I even heard they sold his underwear, for Christ’s sake. Is there anything you would like to say about them?

They have done an enormous disservice to Kerouac, selling off his papers to collectors, censoring scholarship of him, aiming all their efforts at making his work produce the maximum profit. I don’t want to spend more hours here talking about that. I have written about it at length in my recent book Kerouac: The Last Quarter Century.

In an interview you gave to Beatdom in 2021, I was shocked to read about the appalling treatment meted out to Jan Kerouac – not just by the Sampas family but, much to my disgust, by Allen Ginsberg of all people, who had her forcibly removed from a New York University conference on her father. What the hell was going on there?

At the end of his life, Ginsberg wanted major recognition – even a Presidential Gold Medal. He had to work with the Sampases to see certain of his projects fulfilled, like the publication of his letters with Kerouac. He told Jan to “stop rocking the boat,” but the boat he was talking about was his career. Jan was fighting for her own life, and for the fate of her father’s literary legacy. Ginsberg’s supposed “compassion” was often a crock of shit – excuse me for calling it as I see it.

There are many different Jack Kerouacs, it seems to me, not just the man and the writer but the legends perpetuated by critics and fans alike. If there is one thing about Kerouac that people consistently get wrong, what would you say that was?

They don’t understand that Kerouac was always on a spiritual journey, always trying to define and understand his own relation to God and the universe. Even when he was getting drunk, fucking his brains out, he was asking himself questions like, Why is God putting me through all this? That’s deep stuff, and Jack was deeper than almost anyone yet has recognized.

Finally, and I appreciate how broad a question this is, but what do you think is Kerouac’s lasting legacy to literature? Will we be celebrating him in another 100 years?

Absolutely. Kerouac was one of the handful of literary pioneers who took the helm of world literature and steered it into postmodernism, the examination of the mind’s role in creating reality, the vast exploration of subjectivity that is the current state of literature. While minutely recording the details of his own life and world, he was at the same time always looking at how his mind was perceiving and really creating that life and that world. That stuff was hugely revolutionary, though we now know, through the discovery of The Joan Anderson Letter, that Neal Cassady had given Kerouac a big kick in that direction.

Photo of Gerald Nicosia

Memory Babe will be officially released by Noodlebrain Press and published on Amazon and in all good bookstores on September 6, 2022. The author can be contacted for advance copies at [email protected] or PO Box 130, Corte Madera, CA 94976-0130.

About the author

Leon Horton is a writer, interviewer, editor, and member of the European Beat Studies Network, published by Beatdom Books, Beat Scene, International Times, Newington Blue Press and Empty Mirror. His essays include Where Marble Stood and Fell: Gregory Corso in Greece and The Beaten Generation: Burroughs, Ginsberg, Thompson… and the Battle of Chicago. He is currently working on a project with the renowned biographer and punk historian Victor Bockris.

Wonderful interview, excellent questions. I’m waiting happily for the new edition.

Comment by Jami Cassady on 14 April, 2022 at 6:47 pmLooking forward to Gerry’s account of the finding, hassle, auction (s) and history of the Joan Anderson Letter.

Having been a part of it from 2013 onward.

Jami Cassady