The other afternoon, the neighbors’ dwelling we nicknamed, ‘Quarreling House’, bled a lot of eerie blares – rackets that will make you dial up the police and when you will reach them they may ask too many tired questions for your comfort, and yet you will comprehend what the police personage stomachs in this pandemic situation, besides, that you may have called shall satisfy your credos and conscience, and noises that will initiate a tête-à-tête those horrific domestic trials we may have witnessed. Let the afternoon bleed into an evening into a night of unequal squall ferrying fury and frustration to and fro.

Elora told us about the cat family she stocked at the far end of our block, and about the tomcat, starving, yowling and sniffing around the deserted staircase the queen (in case you are wondering, in this household, we call a male cat a tom or a gib if it is neutered, a female one a queen, and the kittens, kittens) gave birth to four kittens. Elora tried to shoo it away, afraid it meant to harm the tiny progenies because she heard some vague accusations against tomcats that they devour their own children. It was a late winter afternoon. The tomcat seemed broader than Elora’s threats. Elora searched for stones, and then the queen emerged from the hideout to fend. Both genders were aggressive, and after a while, the queen gave away one sick and fading away kitten. Elora ran to our house before anything untowardly is witnessed by her. There, there. Prisha patted Elora. I let her drink one-fourth a cup of joe. Poet told her that feral cats do eat the kittens supposed to be dying anyway. It would be a waste otherwise, and it may be a mystical procedure to be one with the fading child. Elora murmured that the staircase remained inside her most clear. Only the stairs existed. Not the house. Perhaps the municipality demolished the house the way they did many in our disappearing quarter. Only those stairs. Nothing above or beside. Elora reiterated.

Prisha began the chronicle of one autumn night at the purple house in her maternal neighborhood. She was seventeen, and her elder brother, drunk for the first time, vomited in her shoes, and hence they snuck behind their own house to cleanse the shoes and sober up her brother under an all iron lion-headed public tap on the pavement. The purple house stood there, silent at first, and then bursting with profanities uttered by the housewife who resided there along with her three daughters and a husband whom until that moment they did not realize as a drunkard and a gambler. The husband, Mr. Shah, was accepting the lashes of cuss words and from the sound – a lot of throwing objects. Every throw had a distinct swish and slash or thud and whump. And Mrs. Shah began to bawl and shriek. Her voice reminded Prisha of the two words she loved back then in her late school days – intense and ghastly. You are seventeen. You have your own elder brother leaning against you searching for your support. The house near you is purple. There may be a murder in progress. Prisha reeled and reclined against the hollow breeze. She nudged her brother for a run back to their house and report so that adults might take responsible actions, There came another screaming; actually, it was a combination of several voices – unripe, mature, undomesticated. Prisha counted in her mind – three daughters (the eldest being of her own age), one woman (the mother), and the man (drunk, sunk in bookmaking, lost in fatherhood). And yet Prisha and her now sober brother desired to remain stuck standing at the same place as if they desired the evil to unlock its worst and its utmost incurable incarnation and be done with the manifestation. However, Prisha shouted that she was about to inform the local police. Her shrill voice must have failed to reach its aim. The ruckus continued. No one was dead yet.

Then. Prisha pauses to look at me as if to weigh my expression.

Then it happened. She says.

Prisha asks if we have heard, at any time of our life, more likely when we are convalescing from some long-lasting ailment, an ‘sznnn’ inside our skulls as if there flows turbulence through the carotid artery or jugular vein, we may understand her ordeal. The noise was silent, absent, blank, bold, deafening. First, there was no other light, except those of the streetlamps and coming from Mr. Shah’s house, and then one intense beam of colorless sulfur scented light descended from the above. The sound was rotating. The house began to float for one breath. It jetted upward into what seemed the center of that light. Prisha and her brother could see the dark sky through the beam. It was transparent, not even translucent, but it was a ray nonetheless. The house, odor, and the ray all disappeared together.

Then? I ask. We ask.

Prisha and her brother told their parents every detail; they, in turn, disbelieved the last half of the narrative and called the police. Police found the house there. Burnt down. Standing zigzag black. Since the teens were the only witness of a mishap, they were grilled by the police and their parents. Nothing was concluded. There was no body, incinerated or alive inside. No one, it goes without saying, saw Shah family again.

We add no more stories.

Kushal Poddar

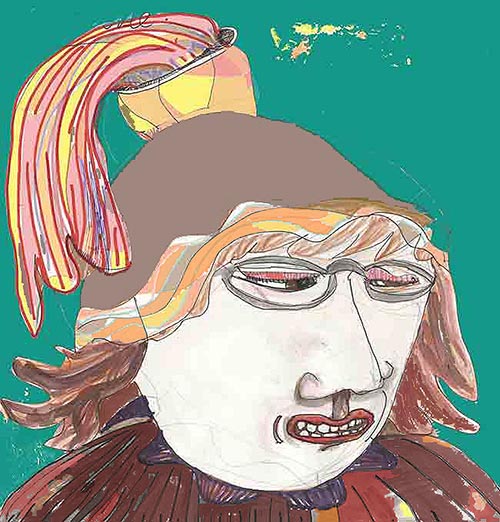

Picture Nick Victor

@amazon.com/author/kushalpoddar_thepoet

Author Facebook- https://www.facebook.com/KushalTheWriter/

Twitter- https://twitter.com/Kushalpoe