Good People, The Lighthouse, Falmouth

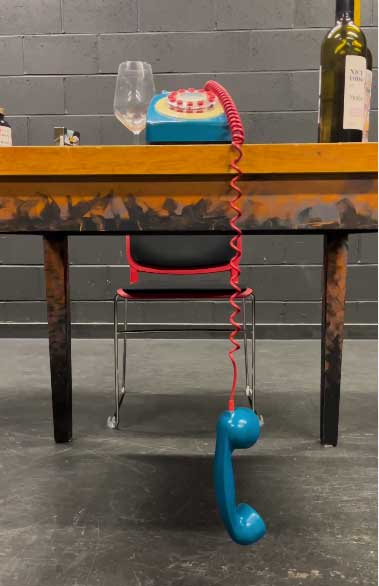

It’s poorly lit when we are finally let in to the intimate space of The Lighthouse for the premier of Georgia Death’s new play Good People. Someone is just about perched on a chair in the stage area, but mostly she is sprawled across a dining room table, which is scattered with wine glasses, cigarette packets and other detritus. Quiet music plays – I only recognised Mazzy Star’s ‘Fade Into You’ – until the lights slowly come up and Martha stirs.

She is drunk, by turns hysterical and maudlin, reflective and angry. She gulps down glasses of white wine, then red wine, lights endless cigarettes, puts them out, picks them up, lights another. She is in shock, she is belligerent and angry, she is in mourning for her mother, who she has been estranged from since she was a teenager.

Martha and the audience do not know whether to laugh or to cry. Is Martha hysterical or hysterically funny? Should we even consider laughing at grief? What are the words? Martha often stops to consult a dictionary on the table to make sure the words are the right ones. She invites us into her confidence: how she feels, why she feels, what she thinks, what happened. What she wanted to happen. What might have happened.

An old rotary dial phone is used as a stand-in for Martha’s mobile when she holds or re-enacts conversations with others. She cries, screams, dances; embraces and sniffs her mother’s coat, abandoned on another chair. Then she pulls a chair towards the audience and sits on it to re-enact the question-and-answer sessions at the local police station: what was asked, what she said, and what she was actually thinking at the time. (Mostly, it seems, about how hot the younger policeman was.)

More wine, more cigarettes, until the past is swept into a binbag along with the debris from the table. Martha’s assertiveness becomes confusion (noun: the state of being bewildered or unclear in one’s mind about something), loss becomes anger, death becomes inevitable. The words become undefinable; Martha is lost and speechless. Alone. Inarticulate.

Teya Nicole Hide’s performance, alone onstage for 50 minutes clad only in a crumpled sleeveless purple dress or slip, is nothing short of miraculous. She singlehandedly brings Death’s script to life, inhabiting Martha’s trauma, cynicism, flirtatiousness and loss, aided by the subtle and minimal sound and stage design. This is a disturbing and profound piece of theatre, which will be touring in 2024. Make sure you see it if you can, and be prepared to be provoked, challenged and pleasantly disturbed.

Jonathan Sinclair

.