The Holy Grail of the Beat Generation

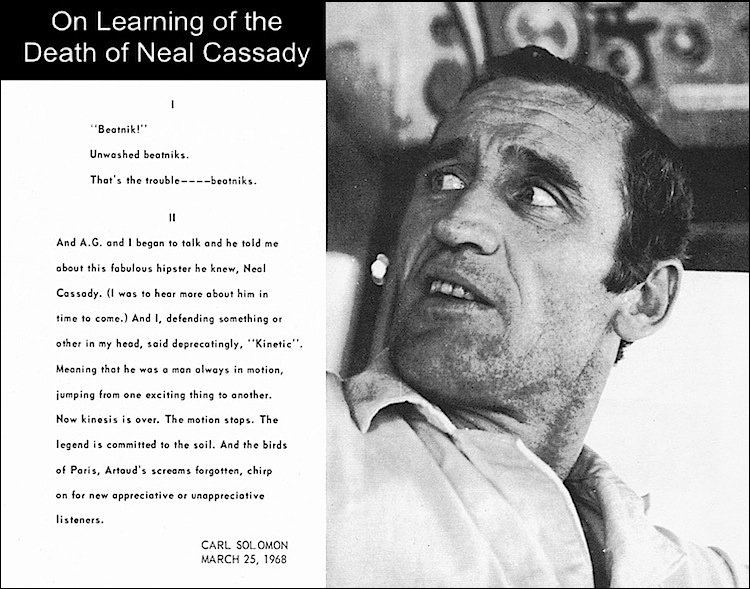

When Neal Cassady died in 1968, Carl Solomon recalled a conversation he had about him with Allen Ginsberg: “He told me about this fabulous hipster he knew. (I was to hear more about him in time to come.) And I, defending something or other in my head, said deprecatingly, ‘Kinetic.’ Meaning that he was a man always in motion, jumping from one exciting thing to another.”

That kinesis—the literary kinesis, if you will, made unforgettably clear in The Joan Anderson Letter—began when Jack Kerouac read Cassady’s spontaneous rush of words and claimed it was more alive than any piece of writing he had ever seen.

In its effusive style, its freewheeling candor, its Proustian (yes, Proustian!) introspection, the letter touched off a response in Kerouac that reshaped entirely his own approach to writing. The result was an explosion of “road” novels, beginning with On the Road, in which Cassady is renamed Dean Moriarity and called nothing less than “the root, the soul” of Beat legend.

Here’s the way Beat scholar and poet A. Robert Lee puts it in his bracing, comprehensive introduction to the first publication of the letter as a complete book in itself:

Even a first read-through could hardly fail to recognize the inscriptive energy celebrated by Kerouac, each story-episode, power of recall, idiosyncrasy. In fiction as in life, and even allowing for spats and fissures, Cassady holds Kerouac’s gaze as though entranced. A near-mythology, understandably, has accrued.

“This is not to step round the suspicion that Cassady sees himself deliberately writing not just to, but for, Kerouac. The one line of story folds into others. Digressions, quixotic, sexual, enter as of the moment. In-house asides and wordplay recur as does a deliberate spot of joke-telling. Literary names, Baudelaire, Melville, Proust, Céline, Dickens among others, he drops in as if to play to the writer in Kerouac . . . The upshot becomes a kind of epistolary theatre, virtually a found novella. But however construed there can be no doubt of its impact on Kerouac: the Holy Grail as he and Allen Ginsberg took to calling it.”

CLICK TO READ.

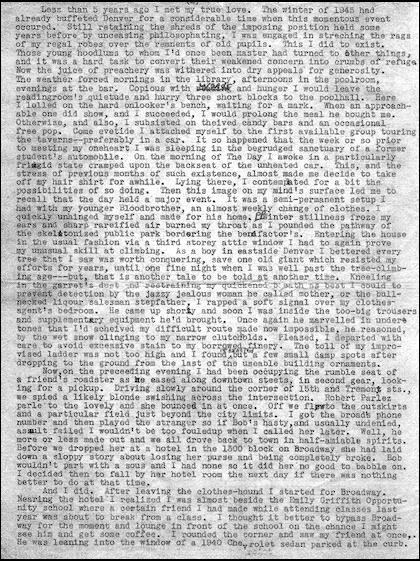

Dated Dec. 17, 1950, the 16,000 words of typewritten, single-spaced pages turn out to be so magnetic they still hold up 70 years later even without the special pleading of a literary investigation. This surprised me because I had been unimpressed by Cassady’s 1971 partial autobiography, The First Third, when it first appeared. I didn’t expect to read his letter in a single gulp.

Cassady was an amateur writer, no question. But he was a highly observant and well-read wannabe, and his psychological insight into the people and situations around him was acute. He was also daring in everything, though often too daring for his own and others’s good, which gave him plenty to write about.

Whether the letter is about sex, drugs, jailbirds, books, philosophers, poolrooms, lovers, libraries, women, or carjacking, it rarely gets dull. And he’s often playful. He coins words, riffs on nicknames. (For Louis-Ferdinand Céline: “Dirty Ferdy, filthy ferdy, lousy louie, looney louie, lucky louie, blue Lou, limpin’ lou, ad infinitum or ad nauseum or et al or etc or on and on and so forth about C.”) But as an amateur writer with a fondness for the greats, Cassady tended to imitate whomever he’d been reading lately. So, for example, when he writes about Melville, his letter takes on the archaic grandeur of Melville’s prose.

“Enfolded in bleak Obispo,” a California town where he was staying with friends, Cassady describes his infatuation thus:

“In one sitting (poor ass) of 30 hours I took between my ears Moby Dick from end to end . . . This copy of Herman’s Hankering was a magnificent Modern Library giant with great pen-and-ink illustrations. Of course, I was inclined not to enthuse over the old boy too much and certainly picked him up offhandedly for I’d read it all long ago. . . . One new impression, especially when compared to long-ago reading; he is simple, writes so simple and is very simple to understand. It’s wonderful that he is so, would that I was as clear, would too that I had his strength as I have his philosophy and death knowledge.”

And he can be too grand, slipping easily into the grandiose:

I am fettered by cobwebs, countless fine creases indelibly etched on the brain. There are no unexplored paths in my mind and few that are not entangled in the weave of my misery mists. It is but gentle fog thru which I navigate and make friendly by constant intimate communion. Within the hour from arising from the suffer-couch, each sleep I’ve gained anew the daily grease for the bearings on which I roll. I embrace to its exhaustion the night’s gleanings with the sure calm now maintained by my dry brittle soul.”

In case you’re wondering why the letter is named for Joan Anderson, it’s because the tale of Cassady’s passionate but unhappy love affair with her is the launching pad for all the rest. Joan is a pregnant, 19-year-old student nurse whose beauty Cassady keeps comparing to Jennifer Jones (a now largely forgotten Hollywood star of the 1940s and ’50s). “The particulars come thick and fast,” Lee writes.

Story enfolds story. Joan’s attempted suicide by the ‘stark cocktail’ of hydrogen peroxide and ammonia and rescue from the balcony ‘by the narrowest of margins’ and the hospital follow-ons for the poisons and then the scar of abortion, bespeaks real human drama. [But] in a kind of perverse parallel Cassady tells the Cherry Mary / Mary Ann Freeland story, this time the sex at any time or place with the sixteen-year-old [is] more akin to comic-cut shenanigans. … The vignette of escaping nude through the family’s small bathroom window (‘nearly took off my pride and joy’) belongs in Tom Jones or a Feydeau farce. The follow-on as lost altar boy godson to Father Harlan Schmidt, and false accusations while in police custody at the hands of Sergeant Tom Garrard of poolhall robbery and rape of Mary Lou, supply a fitting epilogue—buttressed by the Pentecostal faux-sermon. It would be hard to encounter a more eventful plot-line.”

Or a more Dickensian thriller.

Jan Herman

The Holy Grail of the Beat Generation Neal Cassady: ‘The Joan Anderson Letter’