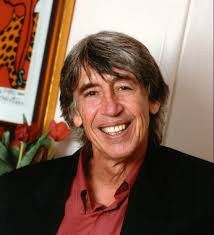

Richard Clive Neville, editor, writer and broadcaster,

Richard Clive Neville, editor, writer and broadcaster,

born 15 December 1941; died 4 September 2016

———————————————————————————————————-

Beyond good and evil

April 15 2002

Sydney Morning Herald

Almost a year ago, Richard Neville wrote a provocative analysis of the “dark side” of Uncle Sam – a nation, he argued, hell-bent on furthering its own interests at any cost. Now, in the wake of September 11, America has cast itself as a global crusader against terror, above the law, above criticism. But is it really on the side of the angels in a “new kind” of war, Neville asks – and could it have responded to the crisis in a way more in keeping with its own high ideals?

On the morning of September 12 last year, my head still reeling from the previous night’s footage of the attacks on New York and the Pentagon, an e-mail burst forth from a US marine. “I bet people like you are happy now,” it said, “probably smiling inside a little, thinking ‘glad it put you in your place’ or ‘maybe now they won’t be so damned arrogant’. I promise you that won’t happen, we will be stronger.”

This message, like several hundred others of varying sentiment, was inspired by the May 19 cover story in Good Weekend, “American Psycho”. The marine had been “meaning to write” since picking up the magazine on one of his frequent visits to Sydney and wanted to republish the essay in his homeland. “I think Americans should know what people like you think of us, and our values. Tell me, what makes you so right, and us so wrong?”

The soldier’s anger that morning was understandable. At that moment I regretted my failure to make clear that my quarry was his country’s imperial state of mind, as seen in its foreign policy and cultural overkill, and not his warm-hearted compatriots, most of whom are oblivious to the deeds done in their name.

George Bush the First had flaunted this imperiousness with a gritty phrase on the eve of the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro: “The American way of life is not negotiable.” If that’s so, I argued in these pages, then it will eventually cost the rest of us an arm and a leg and a lung; maybe more. While I would rather live in the shadow of the White House than at the mercy of sharia law, the policies of Washington, I came to realise, reflect the ruthlessness of corporate America, which treats other lands according to their rating: market, mine, sweatshop or basket case. Uncle Sam’s rapaciousness is both driven and disguised by a mix of pop culture, mass media, brand fetishism and propaganda so clever and tantalising that most of us feel the sooner we’re indoctrinated into the American Dream, the better. Hey, don’t stop the music.

The events since 9/11 have heightened my concerns. The wounded Goliath is on a rampage – armed to the teeth, adored by the polls, unfettered by law, answering to no-one and licensed to kill. Western nations fall in behind the furious avenger, beguiled by the notion of civilisation protecting itself, striding forth with the flame of freedom. Our commentators applaud. The “axis of evil” speech is hailed by The Australian’s foreign editor as a “key defining document of the new era” in which George W. Bush guides us beyond the “magnificent” Cold War strategy of deterrence to the brave new magnificence of “pre-emption”, where the US upholds democracy, topples tyrannies and makes the world a better place.

A better place for whom? Some see Uncle Sam as he sees himself – a Santa Claus for all seasons, dispensing lollies, global justice, gadgets, Oscars, blue-chip stocks and fizzy beverages. Others see him as the school bully in charge of the tuckshop. Perhaps it’s a case of split personality: a good Uncle Sam and a bad Uncle Sam. America provides more freedoms, thrills and opportunities for its own citizens than can be matched by any other nation. The good Uncle Sam regards this as a hot franchise to market for the betterment of all. The bad Uncle Sam wants to preserve the cash flow at head office by any means necessary, even if it destroys the planet and all the wretches who get in the way.

Bush’s “new kind” of war in the name of freedom is actually an old kind of imperial excursion to extend America’s grip on the wealth of the world. A wealth which belongs to everyone. But instead of a misnamed bombing spree, which incubates terror, what the world needs most is an ongoing, unconditional fairness revolution to eradicate the roots of rage. Such a sweeping global ethic is absent from the priorities of the millionaire mogul hawks who run Washington, but it was briefly glimpsed at street level in the rubble-strewn surrounds of the twin towers.

New Yorkers responded to the attack with courage and compassion, refuting their caricature (by me) of being a bunch of hard-nosed money-grubbers bent on ripping off their best friends. A store-owner handed out sports shoes to the women fleeing the mayhem, so they could fling off their high heels. “That is a New Yorker,” noted a senator, “and there are millions of us.” This surge of mateship was matched by a spell of self-examination which offered hope for how the White House might deal with the attacks, once the President could be located. “Let us take time to deliberate,” suggested a foreign relations expert, who argued that military force would be less effective in undermining terrorists than a demonstration of restraint. Others, too, urged the US to hold its fire, and avoid further suffering. The UN or World Court could put Osama bin Laden on trial, “even in absentia”, condemning him and his network as criminals. Some called for a period of deep reflection. These voices were submerged in a sea of flags as the loudspeakers blared God Bless America. Network anchors dressed like brigadiers and frowned over maps. Newsweek beat the drum for military strikes, covert attacks, confiscation of assets, rapid arrests, closure of safe houses, the boosting of state power, regardless of the “prattling of civil libertarians”. For the rest of the world it was, mysteriously, “the end of the free ride” (sic). Foreigners could no longer “denounce America by day and consume its bounties by night”. Our own commentators, adopting the mantle of honorary Americans, echoed these sentiments like drunken parrots, dismissing the few doubters as traitors.

When the twin towers collapsed, so did America’s sense of invincibility. Perhaps this is why the grisly deaths in Manhattan seemed so much more shocking and outrageous than the deaths of hundreds of thousands of terror victims elsewhere in the world. The mob wanted vengeance. “The response to this unimaginable 21st-century Pearl Harbour,” roared Australian expatriate Steve Dunleavy, a columnist for Rupert Murdoch’s New York Post, “should be as simple as it is swift – kill the bastards. A gunshot between the eyes, blow them to smithereens, poison them if you have to. As for cities or countries that host these worms, bomb them into basketball courts.” And so it came to pass.

When the world’s mightiest air force unleashed itself on the world’s poorest nation, the result was never in doubt. Carnage, and lots of it. Among my reasons for opposing the action in Afghanistan was the awkward fact that the Taliban, however insufferable, did not plan or execute the attacks on the US. But why let the truth get in the way of a sitting duck? The Taliban was a vile theocracy which subjugated women, mutilated criminals and disallowed free speech. It deserved to be crushed. Maybe so. In which case, so does our coalition ally Saudi Arabia.

Until recently, the Taliban was seen as a commercial ally. In 1997, its officials were flown to George Bush’s home state of Texas, where they barbecued T-bones beside a swimming pool with the vice-president of the oil giant Unocal. With less than five per cent of the world’s population, the US consumes over a quarter of the world’s oil, for which it relies heavily on imports. On the Unocal agenda was siphoning at least 60 billion barrels of oil (maybe up to 270 billion) from Turkmenistan, part of the last great resource frontier. The plan was to pump black gold across the landlocked wastes of Afghanistan, through Pakistan to a terminal in the Arabian Sea. Until recently, these talks were thought to have collapsed in December 1998, when Unocal pulled out, citing civil unrest.

In fact, soon after its election, the Bush Administration resumed the talks, believing the Taliban could be trusted to support the pipeline, as it supported the War on Drugs. (Washington handed the Taliban $US42 million to suppress the cultivation of opium poppies, now back in bloom.)

Another party to the pipeline negotiations was Enron, the famously bankrupt energy trader which, with Washington’s backing, managed to deregulate, privatise and vandalise several developing nations. Enron’s disgraced chairman, Ken Lay, a former Pentagon economist, was the biggest single investor in George W. Bush’s campaign for president. In return, Lay was able to appoint White House regulators, shape energy policies and block the regulation of offshore tax havens. Enron had “intimate contact with Taliban officials” according to a report in the Web newspaper Albion Monitor, and the energy giant’s much-reviled Dabhol project in India was set to benefit from a hook-up with the pipeline.

These negotiations collapsed in August 2001, when the Taliban asked the US to help reconstruct Afghanistan’s infrastructure and provide a portion of the oil supply for local needs. The US response was reportedly succinct: “We will either carpet you in gold or carpet you in bombs.” The notes of this meeting, which took place only weeks before the strike on America, are now the subject of a lawsuit between Congress and the White House. Was the Taliban really destroyed for harbouring terrorists? Or was it for failing to further the ambitions of Texan millionaires?

At the end of last year, George Bush appointed Zalmay Khalilzad the US special envoy to Kabul. Another appointee, the likable, green-gowned interim president, Hamid Karzai, is credited with setting up a post-Taliban pro-oil regime. Both men are former consultants to Unocal.

Apart from a thirst for revenge and a thirst for oil, the official reason for the bombing of Afghanistan is to eliminate terrorists. In that case, why isn’t America bombing itself? The US is both a retirement village for seasoned terrorists and a traditional training ground, as others have argued in detail. Prominent torturers, executioners and death squad commanders from Chile, Guatemala, El Salvador, Haiti and even Pol Pot’s Cambodia have been resettled in suburban serenity, far from their former killing fields. Florida reportedly seethes with a multitude of hot-blooded anti-Castro saboteurs and hijackers.

The future supply of career sadists is guaranteed by the US Army’s training centre at Fort Benning, Georgia, formerly renowned as the School of the Americas, which makes the al-Qaeda camps seem like a Teletubbies picnic. Among its alumni are South America’s titans of torture, including the former head of General Pinochet’s secret police.

When George Bush depicts his fellow citizens as “good” and his quarry as “evil”, it mirrors the mindset of his enemy, the holy warriors against Great Satan. And it means anything is permitted. In Washington, the torture of suspected terrorists by the FBI and other agencies – either with “a truth serum or beatings” – was promoted at the highest level. The captives at Guantanamo Bay, hooded, bound, head-shaved and spotlit, are deemed the “worst of the worst”, and denied the protection of the Geneva Convention. Those tainted with al-Qaeda connections have been secretly sent to lands where torture is legal, according to a Sydney Morning Herald report which cites the CIA-friendly regimes of Egypt and Jordan. One diplomat crowed: “It allows us to get information from terrorists in a way we can’t do on US soil.” The procedure of extradition is bypassed.

America was congratulated for the speedy assembling of its “coalition”, conjuring up an image of the steely, speedy Orcs mustering Hobbits, with Tony Blair bouncing up and down to prove his inner Orc-hood. America defined the goal, led the chase and dictated the strategy. It seemed puzzling, back in October, that so little time was spent in trying to cut a deal with the Taliban. (Nothing was known then of the oil imbroglio.) Instead, a deadline was peremptorily set to hand over Osama … or else. Not such an easy task, as it turned out. Was there any other way? Perhaps, with time, dollars, pressure from Pakistan and the mediation of senior Islamic clerics, the Taliban may well have been enticed to join the hunt.

The more the war dance hotted up, the stranger became the mood. So much so, I felt I was suffering a spontaneous acid flashback, one of the few mental events a gnarled hippie awaits with delight. The former boss of the KGB, lately the butcher of Chechnya (and now implicated in the Moscow apartment bombings), Vladimir Putin was no longer the goon in Matrix, but an Armani-clad freedom fighter for the coalition. The Chinese leaders, their elbows aching from cudgelling the mild-mannered meditators of Falun Gong, and let’s not mention Tibetan monks, were suddenly champions of peace, love and a global Woodstock. Perhaps the most amazing sight of the ensuing months was Israel’s Ariel Sharon lecturing the world on the horrors of terrorism as his missiles rained down on the Palestinians, his tanks flattening their homes, his assassins on double shifts. As a Belgium tribunal considered Sharon’s indictment for war crimes committed in Lebanon in 1982, the star witness against him, Elie Hobeika, was blown up by a car bomb in Beirut, along with his three bodyguards.

Such was the overwhelming support for the “War Against Terror”, that the Western media became its cheer squad. Early White House briefings had the air of a locker room. Quizzed about the lack of targets in Kabul, Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld snorted, “First, we’re going to re-hit targets, and second, we’re not running out of targets, Afghanistan is…” The press corps exploded with cackles. Meanwhile, the body count mounted, although no-one was actually counting. The Pentagon promised smart bombs and the avoidance of civilian deaths. What we got was 600 cluster bombs (each containing 200 bomblets) and repeated shots of limb-torn children in dirt-floor tents, without access to anaesthetics or even aspirin. Never mind. Uncle Sam launched a token drop of photo-op food parcels promoted as “ethnically sensitive”, containing cookies, jam, peanut butter and moist serviettes. Their yellow packaging, by dumb coincidence, resembled that of cluster bombs. Images appeared of bandaged children who had confused the two, though not on CNN.

The US media complied with the Pentagon memo to “minimise” reports of civilian casualties. Not a problem, responded Michael Barone, a Fox News pundit. “Civilian casualties are not news. The fact is that they accompany wars.” The fact is, this war was triggered by a slaughter of innocents and that became its ultimate justification. Fox News, owned by Rupert Murdoch, put a pistol-packing reporter into Afghanistan who vowed to kill on sight “that dirtbag” Osama bin Laden. Fox encouraged its newshounds to “tap into their anger and let it play”. Murdoch execs proclaimed: “Morally neutral journalism is now inappropriate.” As directed, the tapes of bin Laden’s ravings were shelved.

In Australia, the media seemed a little more relaxed, thanks to SBS and the syndication of newspaper stories from Europe, although deep criticism of our ally was rare. While not to everyone’s taste, John Pilger’s coverage of trouble spots over the years and his prickly media profile should have earned him a place on local Opinion pages. It didn’t. Arundhati Roy, who had triumphantly toured Australia with her Booker prize-winning novel, The God of Small Things, published a lucid essay in The Guardian on the darker forces propelling the war. It was not seen here. In the US, it was rejected by every major magazine. From all this battening down of flagship hatches, however, something interesting happened – the Web was reborn as a vibrant nexus of a media revolution.

Even before the bombs fell on Afghanistan, the missiles of Noam Chomsky surged through cyberspace. One day a public cyber library will be built in his honour and our children will toast his devotion to freedom of thought. “When IRA bombs were set off in London,” he noted, “there was no call to bomb West Belfast … or Boston, the source of much of the financial support for the IRA.” It was rather a matter of finding the perpetrators, putting them on trial and addressing the grievances.

It may have surprised Americans to be informed by Chomsky that the only nation ever condemned by the World Court for perpetrating international terrorism was their own. In 1978, when Somoza’s dictatorship of Nicaragua was sent packing by the Sandinistas, Washington had dreaded “another Cuba” and tightened the economic thumbscrews. Later, during the Reagan years, the anti-Sandinista strategy turned deadly. Washington’s proxy army of contras set about sabotaging the county’s infrastructure, including schools, ports and health clinics. During this time, in which tens of thousands of people reportedly lost their lives, the contras raped, bombed and tortured. Nicaragua initiated proceedings in the World Court, which in 1984 ruled in its favour. The US was condemned for the “unlawful use of force” and ordered to pay reparations. Instead, the US escalated the attack. The State Department approved the CIA’s creation of a “terrorist army” to destroy “soft targets” in Nicaragua, including agricultural co-operatives. A UN General Assembly resolution (passed two years in a row, with the US and Israel opposing) called for the US to observe international law. This was ignored.

Another fact-packed anti-war Web site is that of William Blum, founding editor of the ’60s underground newspaper Washington Free Press. Today, Blum is still looking for trouble. “Accessing this site automatically opens a file for you at FBI headquarters,” is the greeting of his home page. “This warning, of course, comes too late.”

According to Blum, from the end of World War II to the beginning of this century, the United States has “attempted to overthrow more than 40 foreign governments and to crush more than 30 populist-nationalist movements struggling against intolerable regimes.

In the process, the US has caused the end of life for several million people, and condemned many million more to a life of agony and despair.” Blum makes the point that Americans are taught it’s wrong to murder, rob, rape and bribe, but that it’s okay to topple foreign governments, quash socialist movements or drop powerful bombs on foreigners, so long as it serves the national interest. From plenty of examples which prove, despite the current rhetoric from the White House, that the West is not always on the side of the angels, these three capture the essence of much US foreign policy: l 1985, Lebanon. The CIA plants a truck bomb outside a mosque in Beirut, aiming to kill a Muslim cleric. As the faithful leave the mosque, the blast kills 80 and wounds 250, mostly women and children. (By comparison, the March attack on a Protestant church in Islamabad killed five worshippers and injured 40.) In Beirut, the targeted mullah was unhurt. None of the victims was compensated.

* 1989, Panama. After sustained Orwellian “hate week” campaigns against former US ally and puppet president Manuel Noriega, along the lines of those previously directed at Fidel Castro, Colonel Gaddafi and Saddam Hussein, an aerial assault is launched on Panama City. The official reason is Noriega’s drug trafficking, long known to Washington. Another motive is maintaining control of the Panama Canal, in the face of populist stirrings. An activist tenement barrio is bombed to rubble, a compliant government is installed. Various independent inquiries put the deaths between 3,000 and 4,000, most of the corpses still rotting in pits on US bases, off limits to investigators. American news networks did not regard the UN’s overwhelming condemnation of the attack to be worth broadcasting.

* 1998, Sudan. The reign of Bill Clinton, the first black-schmoozing rock’n’roll pot-head President, is now derided as a time when America went soft on recalcitrant regimes (a period of “turning the other cheek”, as one dipstick Sydney Morning Herald columnist put it). How soft is soft? In August 1998, Bill Clinton sent Tomahawk missiles to flatten the Al Shifa pharmaceutical plant in the Sudan, claiming it was concocting chemical weapons. Actually, this plant had bolstered pharmaceutical self-sufficiency, and produced 90 per cent of the drugs needed to treat malaria, TB and other diseases. Accusing its owner, Saleh Idris, of associating with terrorists, Washington froze his London bank account. The case was contested and the US backed down.

The Sudan’s death toll from this attack “continues quietly to rise”, notes Chomsky, citing the “tens of thousands of people, many of them children”, who have suffered or died from a range of treatable ailments. The chairman of the board of Al Shifa, Dr Idris Eltayeb, remarked that the destruction of his factory was “just as much an act of terrorism as the twin towers – the only difference is we know who did it”.

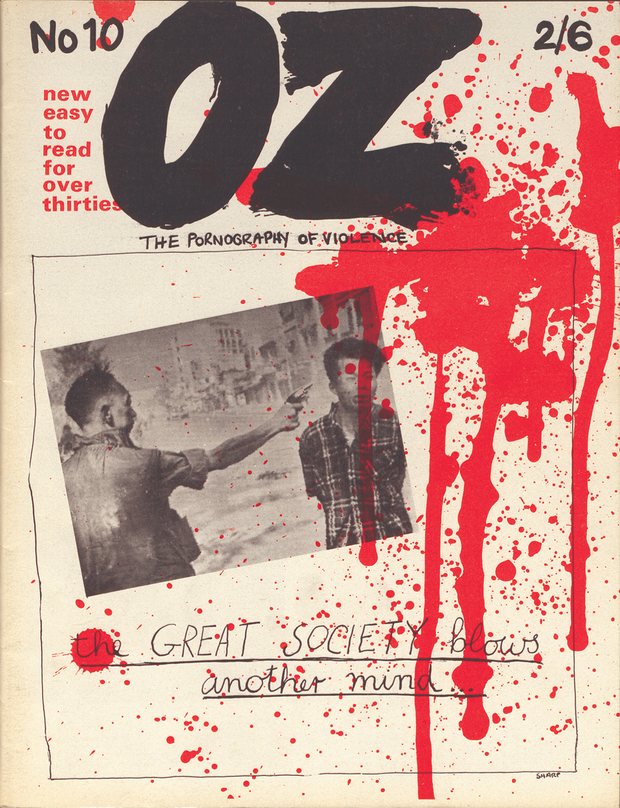

A perspective at odds with the one espoused by Roger Ailes, chairman of Fox News: “What we say is terrorists, terrorism, is evil, and America doesn’t engage in it, and these guys do.” One is reminded of Big Brother’s slogans in George Orwell’s laboured masterpiece, 1984: “War is peace, love is hate, truth is lies.” In this dark vision, the Ministry of Truth manipulates the media to suit the political objectives of Big Brother. In our world, the media are fun-loving and raffish, but the core priorities reflect the priorities of people in power. Images of the twin towers’ collapse are indelibly impressed on the planet’s collective memory. And so they should be. But other images have vanished from history.

In the 1990 Gulf War, a bomb hurtled through the air duct of Baghdad’s “safest” shelter, burning alive 500 people, mainly women and children. A documentary looking at US foreign policy from an Islamic perspective, Letter to America, recently screened on SBS, shows footage of relatives in the ruins of the Baghdad shelter weeping over rows of charred corpses. For such victims, no memorial service, no replay, no justice.

The toppling of the Taliban is portrayed as a triumph, and perhaps it is, for the victors. On the ground, improvements are marginal. An early image of liberation was of Kabul’s haggard residents watching TV, a seamless advertisement for freedom. Except, whose TV? The last US bomb on Kabul hit the studios of al-Jazeera, the independent voice of the Middle East. Funny, that. The Afghans may now need to settle for CNN and Fox, a victory, perhaps, for civilisation and US exports, as well as for the pipe dreams of Unocal. The Pentagon claims this “smart bomb” lost its bearings, as another one did over Belgrade in 1999, when it flattened Serbian TV, killing and maiming the staff.

For the Pentagon, media-seeking missiles are not enough. In February, it announced plans to provide news items to foreign journalists, “possibly even false ones”, in order to manipulate emotions.

After three months’ bombing of Afghanistan, an estimate of civilian casualties was hard to find. It took Marc Herold, an economics professor from the University of New Hampshire, to amalgamate the disparate reports of “collateral damage” and come up with a total. If the evidence conflicted, said Herold, he settled for the lower death count. The number of injured was not included, not even of those likely to die from their wounds. Let me ask you, dear reader, in this ongoing “war against terror”, how many innocent Afghans have lost their lives? If the number is unknown to you, what does that say about our media culture? At the very least, according to Marc Herold, the death toll is 3,700 – greater than the number slain in the twin towers. In January, Herold told ABC Radio that “a much more realistic” estimate of civilian deaths is 5,000. His research covers only the period from October 7 to December 10 last year, since which time the missiles have continued to rain upon Taliban and toddler alike.

Herold’s estimate was given wide publicity in Europe, and next to none in America. Surprised that the US “quality press” had been so circumspect, I e-mailed the casualty count to a journo mate at The Washington Post, asking, why the blackout? His reply was cool: “I think you would find most people here focused on our own thousands killed intentionally.” End of discussion. The loophole, it seems, is intention. Civilian deaths are the price of ridding the world of terror. When B52s are sent to unknown lands with big payloads and bad intelligence, it is certain that civilians will die. Surely such a strategy reveals a “reckless disregard for human life”, a legal definition of murder.

In December, Marc Herold stopped counting and the military action shifted to the Afghan mountains of Tora Bora, focusing on al-Qaeda and its leader, Osama bin Laden. How hard could it be, tracking down this tall, sick, neurotic figure attached to a dialysis machine?

He was hiding in a cave, but which cave? It didn’t matter. The Pentagon had a plan. It would blast apart every cave in Afghanistan. Enter the “daisy cutter”, a 4WD-sized bomb whose name evokes a firework display with floral motif, and which packs the punch of a tactical nuclear weapon. It is triggered above ground to clear vast surfaces of all structures and life. The blast inferno vaporises everything within hundreds of metres and produces a mushroom-shaped cloud, resulting in a vacuum of such force that it sucks out human eyes. A rush of oxygen then reignites what’s left and sets off another explosion. In a sane world, the daisy cutter would be banned; right now, it’s despoiling everything in its path.

During four weekend raids that struck villages near Tora Bora, at least 80 non-combatants were killed, according to pro-American local commander Hajji Muhammad Zaman, who kept asking: “Why are they hitting civilians?” Meanwhile, George Bush brooded over his dead terrorist scorecard on the White House desk, ready to cross out the names of senior al-Qaeda officials. “I’m a baseball fan,” he told Bob Woodward of The Washington Post, “I want a scorecard.” Alas, it was left largely incomplete, as the opposing team slipped away, not for the last time.

On January 24, enter the US special forces, and an attitude of “whatever it takes”. A stealth attack on two small compounds in Hazar Qadam resulted in the deaths of up to 21 Afghans and the capture of 27 others. Released two weeks later, the men revealed they had been severely beaten and rib-kicked. Rumsfeld later admitted these Afghans were not, as first announced, Taliban or al-Qaeda fighters, but troops and local officials loyal to the current government. Photos appeared on the Web showing bodies of those shot displaying white plastic wrist restrainers bearing the words “Made in USA”. As pointed out by the US magazine The Nation, Article 23 of the Hague Convention forbids a warring party “to kill or wound an enemy who, having laid down his arms, or having no longer means of defence, has surrendered”. General Tommy Franks, the head of the US Central Command, defended this apparent war crime: “I will not characterise it as a failure of any type.”

By mid-February, the baseball scorecard of George Bush was still blank. The Pentagon and the CIA dispatched a missile to kill three men near the village of Zhawar Kili, close to the Pakistan border. The reason? One was tall. “Maybe it’s Osama.” In fact, it was three impoverished scavengers, now obliterated. A Washington Post reporter who tried to poke around the scene was turned back at gunpoint by US troops. Rear Admiral John Stufflebeem lost his cool: “The Taliban has vanished. Al-Qaeda has vanished. It’s a shadow war; these are shadowy people who don’t want to be found.” That’s the thing about terrorists. They can’t be trusted to die easy.

Stufflebeem got one thing right – it is a war of shadows. Whose shadows? Who has the most to gain? An interlocking network of owerbrokers in oil, arms, politics and media, for whom the world is a goldmine and this war their windfall.

Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, for instance, is a boardroom veteran of the mighty Tribune Company, publishers of the Los Angeles Times and Chicago Tribune. He is also a former director of Gulfstream Aerospace, acquired by General Dynamics in 1999, a deal which netted him a cool $11 million. What is General Dynamics? A major defence contractor. And so it goes. Early warnings to the White House of Enron’s hidden debt must have been timely for the 35 Bush officials holding its stock, including Army Secretary Thomas E. White, whose portfolio had topped $US50 million.

But there is another America. A questing, compassionate America, which yearns to share its good fortune with the rest of the world and break the psychic gridlock of us/them, good/evil. New York on Valentine’s Day saw the launch of a poignant initiative, “September 11 Families for Peaceful Tomorrows”, named from an utterance by Martin Luther King: “Wars are poor chisels for carving out peaceful tomorrows.” One member, a woman whose husband died in the twin towers, said she resented being used as an excuse to start a war, “a horrific thing, the idea that someone would do this for me to someone else”. Peaceful Tomorrows raises funds to help the families of the Afghan dead, the widows now sending their toddlers to beg. Such a spirit may jolt Americans to consider the rest of the world’s pain, as it jolts me to honour that country’s ongoing contribution to the evolution and celebration of humanity.

Like the 17 founding families of Peaceful Tomorrows, it is time to transcend the belligerent imperialism of Old Guard America that is prepared to ravage the whole of earth in order to foster, for its spoilt elite, a lifestyle of careless opulence.

The promise of globalisation is a shared destiny of nations working together to minimise conflict and poverty, restore ecosystems, reduce emissions, ban arms trafficking and thrash out an evolving agenda of ethics and fairness to which all can be a party, especially the strong. Its deeper meaning is a belated awareness that we are all connected – and connected in a deeper way than the choice of being with America or against America, of being a target market, or a target.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Neville_(writer)

Obituary

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2016/sep/04/richard-neville-obituary

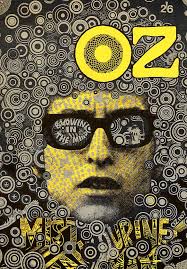

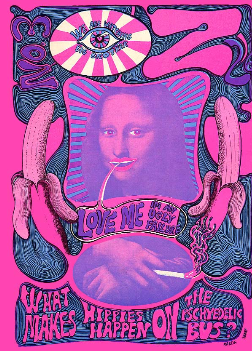

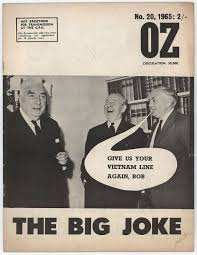

Photos from the Internet