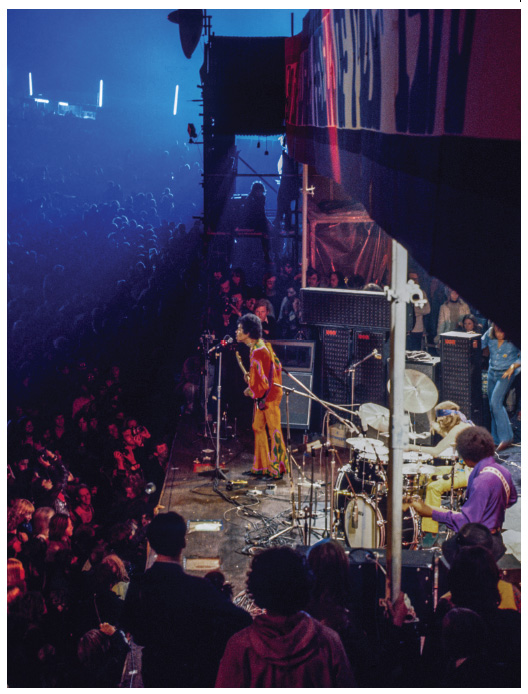

This book starts with the electrifying shock of the death of Jimi Hendrix in September 1970.

With the superstar at the peak of his game, his sudden death feels raw and personal. With him having played at the Isle of Wight Festival only two weeks before, the organisers, the Foulk brothers, feel the loss explosively. Described as “Magnificent but fragile” as he entered the festival arena, it could have happened at their festival.

The news reverberates around a grand office drowning in debts and clamours for money, the fall out of the huge festival battered by the concerted efforts of a few anarchists to force it into being a free festival. The price of a ticket was only £3 (even comparing the rate of inflation, cheap for five days of world class musical entertainment), but the underground swell and intense media focus on this single aspect was enough to bring down the walls. This is a tale of headaches and heroism in extremis.

The book by promoter Ray Foulk is part autobiography, a sequel to Stealing Dylan From Woodstock, which recounts his coup of securing Bob Dylan for the Isle of Wight Festival in 1969. This was in turn the result of the Foulk brothers’ (Ronnie, Bill and Ray) successful first festival in 1968, an event which began with the somewhat humble intentions to raise funds for a swimming pool on the island by putting on a jazz festival.

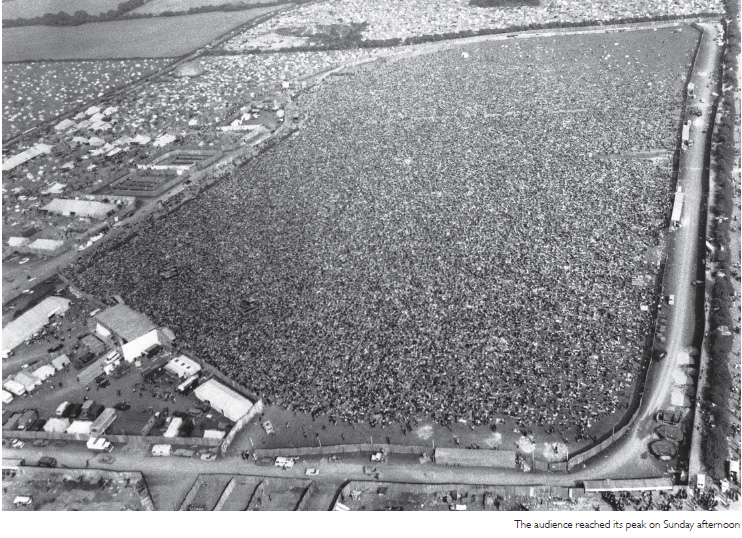

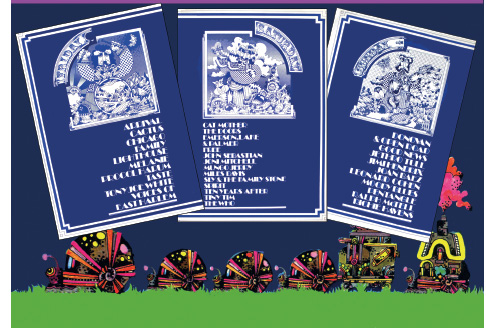

From Stealing Dylan from Woodstock

We had on our hands one of the largest peacetime gatherings in history

It was even bigger a year later, the final festival being the subject of this book, The Last Great Event. This title may appear at first ostentatious until the story of the festival and its astounding roster of artists unfolds, and you ask yourself if the world will indeed ever see it’s like again. Large festivals of this kind were in their infancy in the late 60s, and while the following forty years have produced an evolving array of astounding rock and pop music, artists, events and festivals to rival an artistic renaissance in any age, there was something about the unique magic of that time, and the dazzling presentation of artists who still sell records and influence young musicians today, that you feel may never be repeated.

Several hundred thousand peace heads make their way over the sea to this most un-hip of locations, an island off the British mainland, a pilgrimage, on a mission, for a cause.

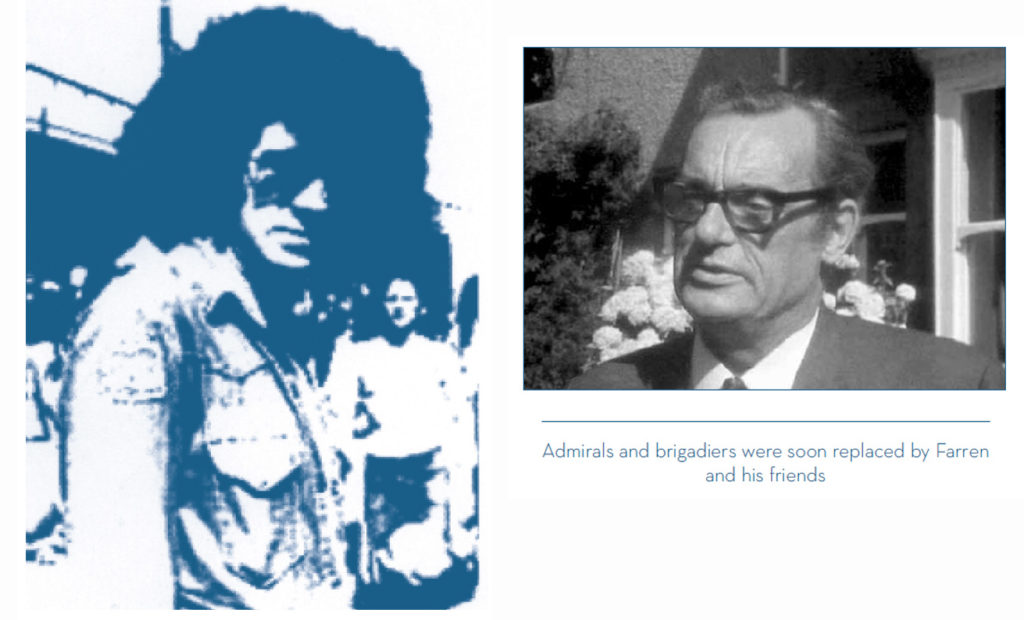

The third Isle of Wight Festival is the biggest. But all is not well in this hippy Shangri-la. Mick Farren (International Times) and Richard Neville (Oz, Freek Magazine) and Friends Magazine are adversaries and betes noirs from the outset.

“Devastation Hill”, where people watched the festival for free

“Devastation Hill”, where people watched the festival for free

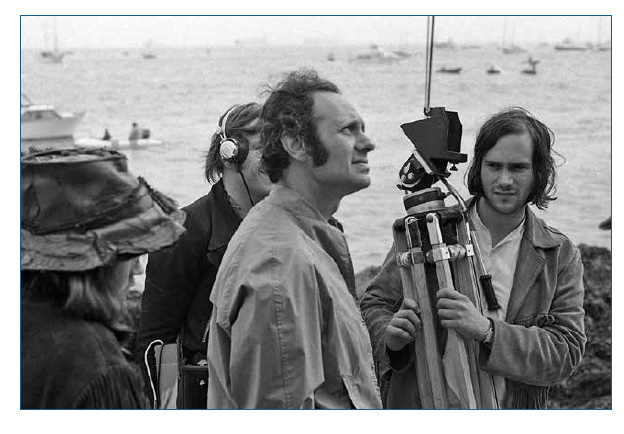

Despite their generally favourable reviews of the festival and artists, there is unfinished business and an undisguised resentment, as if the author must cathartically set the record straight with the alternative press and all the other forces hell bent on stopping the festival taking place. On one side is the clamour for a free festival, with the help of some French anarchists, juxtaposed with an array of world famous artists, many of whom refuse to perform without payment. What to do? The promoters’ money is coming in via cash off the gates, the anarchists are demanding a free festival where nobody hands over money. Then there are the local MPs and Admirals and Brigadiers, a powerful force on the Island, determined to stop hordes of young freewheelers descending on it. There is also the settling of scores in this book with the Oscar winning Hollywood film director Murray Lerner, who twists the action for a sensationalist and somewhat unfaithful representation in “Message to Love”, a cult film never properly promoted. The eleven films he made of the festival are of well crafted excellence and still shown today on Arts channels, a masterful achievement for him and his crew over five days of arduous conditions, the results being a truly historic archive of film of the time. The main film, however, will be a source of aggravation explored in minute detail in the book.

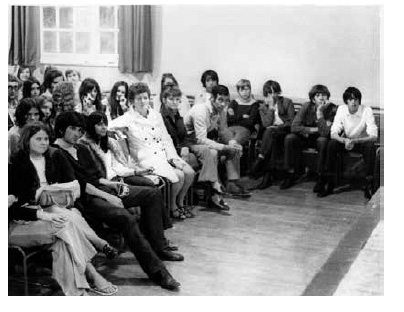

The Foulk Brothers aka Fiery Creations, (right)

The Foulk Brothers aka Fiery Creations, (right)

with some youthful supporters at a town hall meeting

Film director Murray Lerner (left) and Bill Foulk (right)

Film director Murray Lerner (left) and Bill Foulk (right)

Only 24 at the time, with much of the responsibility for making this a success riding on him, Ray has captured both the era and the festival in all their glittering brilliance and madness, with the help of the impressive writing talents of his daughter Caroline. Only a small child at the time of the festivals, she nevertheless helps bring to life the terrifying yet thrilling “on the tiger’s back“ experience any festival organiser will recognise with great skill, wit, and an insight helped by personal family-like connections with many of the colourful and entertaining leading local characters, who all helped to put the festival on in an almost homespun way. It’s her easy going affability and natural style which makes this a page turner, capturing the belly laugh humour of pre-Health and Safety front and backstage shenanigans.

It is also Ray’s archives and service to memory, respectfully naming every single band member who performed at the festival in boxes aside the text, and all personnel involved in its creation, that adds to the historical relevance, not just as a musical memoir, but one that captures the whole zeitgeist of Britain in 1970 in an honest, critical and subjective way.

Mick Farren, described as “Grand Vizier of the White Panthers”, resurfaces, shark like, throughout the book. His presence is a constant thorn in the side of the promoters throughout the entire festival, and a bitterly unresolved one. He refused an interview with the author shortly before his death in 2013, as if to emphasise his determination to hold fast to the anti-capitalist ethos and ideals he fought for at the time and throughout his life. It is salient to observe that International Times and The Isle of Wight Festival are both still going strong in 2016, the former still adhering to the radical ideals of the 1960s, the latter a highly corporate enterprise.

That aside, it is, however, also the nerve-grinding rollercoaster ride of festival promotion, at every level, swerving from organising the toilets to negotiating contracts with superstars, that makes this book quite hypnotically gripping. Take the situation on the island, when we are transported from the shock of Jimi’s death to his imminent performance at the festival:

Eighteen days earlier. By late afternoon, Jimi Hendrix’s road crew had told Ralph McTell that Jimi was still in some debutante’s back garden on the other side of the Island. They said we would have to drag him out and tie him to the microphone if he was going to play at all. By 6 pm even that whisper of doubt was murderous to our nerves. For Ronnie and me, the arrival of our main man was everything. The minutes were dragging out. Then, out of the blackness, Hendrix strode purposefully forward, an apparition preparing to enter the citadel. From his vehicle to his dressing room trailer he was in reasonable time, but tension mounted.

The heroic natural landscape of the Island’s chalk downs, colourfully populated by hippies, flags and tents, formed the southern flank of the already vast arena. With 250,000 souls, the panorama knew no historical precedent. Not even the spectacle of Circus Maximus could have compared. The patchwork of humanity had knitted together over five days. I could not comprehend the measure of it backstage but when I crept up to the wings it gripped me by my senses: the enveloping sound, the epic sight, the multifarious odours. The distant beacons, delineating the arena, were fluorescent strip-lights in the gloom. They stretched back – miniscule glimmering dashes among a multitude of flecks peppering the night. Those camped illegally on the altitudinous downs provided splashes of fire and torchlight, creating the sense of a tremendous crater, almost interplanetary in scale; alien, like an extra-terrestrial army.

Like lights in the festival arena, interesting anecdotes twinkle:

Pink Floyd’s road crew helped with Jimi’s stage rig and, extraordinarily, David Gilmour, who happened to be hanging out backstage, was persuaded to take the desk and mix the sound for the performance.

It also skilfully weaves in the political landscape at the time throughout the book: the counterculture, the anarchy, the civil rights movement, CND and other humanitarian and anti-war campaigns, making this book far more than just music memorabilia, Ray himself being a staunch Labour supporter and pivotal in starting a CND faction on the Isle of Wight.

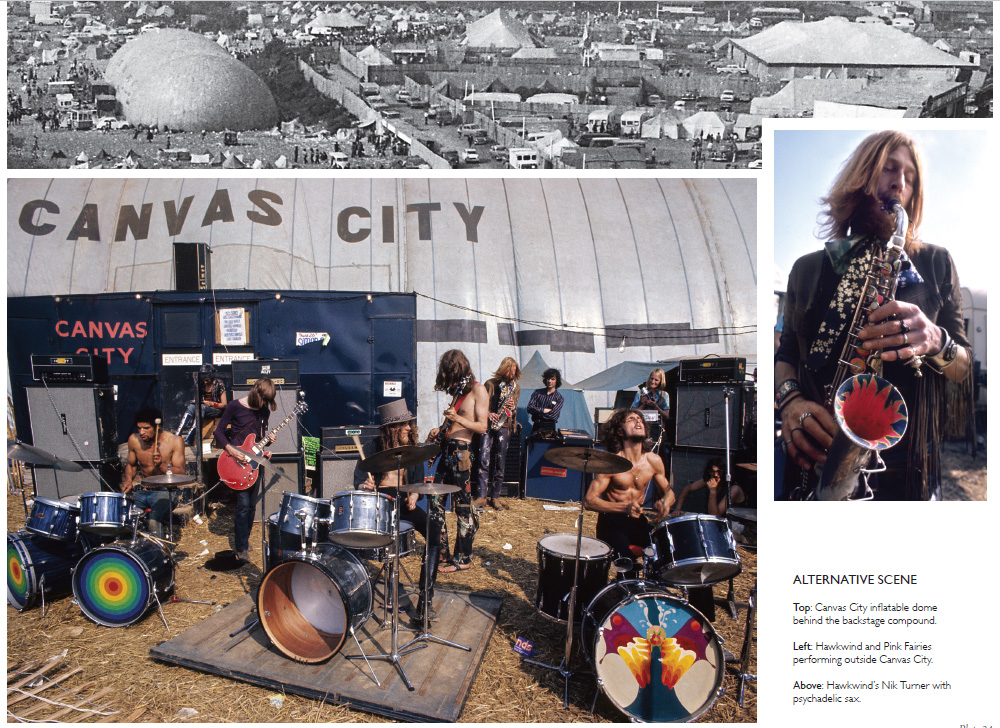

Mick Farren meanwhile gets his dream, setting up an alternative fringe tent at the festival with the Pink Fairies and Hawkwind entertaining many of those who attended for free, the occupiers of the so called Desolation Row, and Desecration Hill, an oversight by the promoters whereby the non-payers could observe the festival for free.

“Canvas City” the alternative festival, outside the main arena,

featuring Hawkwind and the Pink Fairies

Mick and his anarchists have a whole chapter dedicated to them and their alternative festival alongside the main one:

Little did we know but, on that same day, there were auspicious rumblings in the woodlands around Worthing, West Sussex, where a small but notorious festival was just getting under way: Phun City, promoted by our adversary-to-be, Mick Farren of IT, the underground newspaper previously titled International Times. The extent to which proceedings at this event would colour the Isle of Wight Festival would only become evident much later. Our principal local opposition, headed by admirals and brigadiers, was soon to be replaced by Farren and his friends as the event grew closer – a development not lacking in irony since the previous battles had involved our tireless defence of the hippie fraternity, including its more radical and outlandish elements.

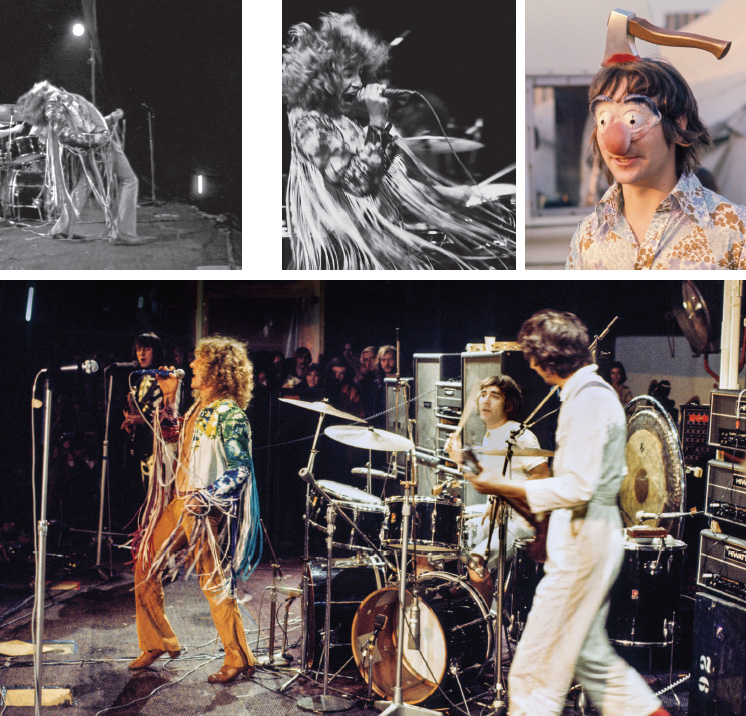

Meanwhile, back on the main stage for the paying guests, the stars roll out like a who’s who of rock music of the day. From the delicately poetic Donovan, Joni Mitchell, The Moody Blues, Melanie and Leonard Cohen to the wild performances of Jethro Tull, Emerson, Lake and Palmer and the Who, there is also an ominous performance by Jim Morrison and the Doors, performed on a more or less darkened stage, capturing the unnerving horror of war and darker aspects of the late 1960s. There is also Miles Davis in a career altering performance, his radical jazz album Bitches Brew showcased, becoming the crazy, discordant theme music associated with the film, the festival, and the swooping pictures shot from a helicopter of the festival site.

The arena was bathed in the glow of early evening autumn sunshine as Miles and his band took the stage, looking more like rock stars in red leather, velvet, sequined jeans and headbands than anything recognisable from the jazz world. Even Miles’ trumpet was black lacquered, with a visual potency akin to a Hendrix Stratocaster. …

Friends thought it ‘The strangest choice of the festival’ but also acknowledged Miles as ‘definitely the most musically satisfying’. Musically, it probably was the most interesting and important contribution to the entire event – more so than anything at any of our festivals, or at Woodstock either, for that matter…Although the audience and critics enjoyed this wild card for a predominantly rock event, few would have been aware of the significance of the moment in the development of his own genre.

The festival scene today, with its high prices and commerciality, really does give food for thought as to whether free festivals, so passionately espoused by Mick Farren and others, could have taken the world in a different direction. Jim Morrison’s tumultuous, doomladen performance of his crescendo song “The End” was apt.

There are two sides to this coin, the one being that in a utopian world there would only be free festivals (and there are many smaller alternative free festivals increasingly springing up today) the other being that everyone involved always wants and indeed needs to get paid, the artists included. Only when everyone does it for free will festivals be free. Pete Townshend of the Who makes his feelings clear after appearing at both Woodstock and The Isle of Wight:

“At Woodstock, people were so appalled when the Who asked for their money – having just travelled 7,000 miles to get there. I said to some guy: ‘Listen, this is the fucking American dream, it’s not my dream. I don’t want to spend the rest of my life in fucking mud, smoking fucking marijuana. If that’s the American dream, let us have our fucking money and piss off back to Shepherd’s Bush where people are people.’ All those hippies wandering about thinking the world was going to be different from that day. As a cynical English arsehole, I walked through it all and felt like spitting on the lot of them and shaking them and trying to make them realise that nothing was going to change. Not only that, what they thought was an alternative society was basically a field full of six-foot deep mud and laced with LSD. If that was the world they wanted to live in, then fuck the lot of them.”

The Who performing at the festival: drummer Keith Moon (top right) larks around backstage

The more genteel Joan Baez also voiced her opinions:

Surrounded by journalists with microphones and cameras pushing right up to her face, she was asked what she thought about the anarchists attacking the walls and demanding a free festival. “The question of kids now wanting everything to be free is very hard to handle, because it’s hard to talk to those kids.” Even for her, asked a journalist. “Even me? Of course. I represent to them, among other things, somebody who has money, and that makes them angry. So if I charge fifteen cents for a concert that’s fifteen cents too much. But, I’m not going to be forced into giving a free concert because they insist on me giving a free concert. That doesn’t make sense either. But in this generation – I mean these kids have been handed down an evil, stinking, rotten world, and they’re rebelling against it. They’re sick of it and one of the ways of saying it is I’m not gonna pay for it.”

This really becomes something of the theme of the book. The Foulk brothers find themselves in the bizarre position of fighting the establishment, for whom they are seen as rebels, and the anarchists, for whom they are seen as the establishment.

Mick Farren (left) and local MP Mark Woodnutt (right)

Mick Farren (left) and local MP Mark Woodnutt (right)

both opposed the festival, though for very different reasons

The ongoing conflict with The White Panthers, the derivative movement of the Black Panthers, run by Mick Farren is described in the press:

“…cultural revolution through total assault on culture, which makes every use of every tool, every energy and every media we can get our collective hands on…our culture, our art, the music, newspapers, books, posters, our clothing, our homes, the way we walk and talk, the way our hair grows, the way we smoke dope and fuck and eat and sleep – it’s all one message – and the message is FREEDOM.”

Compere Rikki Farr also piled into the debate:

“I had mixed feelings about the whole thing from the start…I guess that somebody with more self-control might have kept it together. But what really fucked me up was when all those silly pricks started calling me capitalist. When they start laying that capitalist sort of bitch on you, I see red. And then they try and couple it with the fact that three pounds for this festival is a rip-off. Well I say they are assholes, fucking assholes. I get angry. They are just screwballs. The system doesn’t allow us to be any different at the moment. There’s no point in saying record companies will pay for it. They won’t. Groups won’t play for free. We’ve tried every way.”

…On cue, the opening strains of ‘Amazing Grace’ reverberated across the arena. The audience responded with hundreds of thousands of peace signs. Rikki remained static, arms aloft, for the first minute and a half of the festival anthem before speaking. “Join your hands together. Hold hands with one another. Please, everybody just hold your hands together. Stand up please, as one person.”

Other characters of the day pepper the narrative: Caroline Coon, who ran Release, a drug rehab charity, and Ronan O’Rhailly who established the original pirate radio, Radio Caroline.

The musical sets from all the artists are described in atmospheric detail, Sly and the Family Stone coming on (somewhat unthinkably today) at 7am, the only artists refusing to be filmed, despite the fact that they give one of the greatest, funk fuelled performances of the entire festival (following allegedly the best back stage party too), with the film director Murray Lerner trying to persuade them it was the perfect time for shooting film footage, to no avail. Despite many of the interminable delays, it’s the music that over-rides all the problems in the end, plus the overwhelmingly gentle hippy audience, enraptured and concentrating, even when artists are coming on as the dawn breaks. The momentum builds as backstage tensions mount as managers argue over which artists will have the most coveted slots and it’s all ofcourse, leading up to the star act, Jimi Hendrix.

Something clearly changed, with the demise of both the festival and the pirate stations, when authority finally won out over freedom.

**********

I was involved in an attempt in the mid 1990s to revive the festival with Ray, Bill, Caroline and many of the original team, and several members of the Glastonbury Festival organisation, with the cream of the Britpop music explosion as the roster of acts we had lined up. I can testify to the ideals of the author – our aim was to regenerate the Isle of Wight for its youth by ensuring a week long festival of art and music all across the island, similar to the Edinburgh fringe, unlike the standard prototype of some burger bars, a big wheel and corporate sponsorhip of today’s multitude of festivals. Our vision was so much more than that.

Of course some years later John Giddings, who, as a young man attended the original festival, succeeded in reviving the Isle of Wight Festival and it is a much loved fixture on what now is a booming festival scene. This is all covered in the final section of the Isle of Wight Festival’s Legacy. There has also followed, since 1970, over forty years of amazing stars and music that I believe will be looked back on as a golden era of music which had its roots in the 1960s and the ethos of young people back then, and those brave enough to be pioneers in promoting it. Freedom, love and peace will always be somewhere at the heart of great music. Most of the greatest names of rock music today have appeared on the Isle of Wight stage, carrying on the legacy.

This book is a tale of those lost times, etching these festivals into the history of British rock music. In Ray’s own words, they put on a five day festival for 250,00 people (though the Guiness Book of Records has it at 600,000), the majority peaceful and totally into the love and peace vibe of the day, all fed and watered, and a psychedelic, sunny, unforgettable time was had. An astounding achievement, even by today’s ultra slick standards. And that’s the real story. The price of the ticket was a fair exchange, which is all most people ask for. So much of Capitalism today is an unfair exchange on many levels, the reason for ongoing anarchy and opposition, which is why we have to keep up the fight.

The word “Wight” means spirit, and a sense of the Muse haunts the island, in written terms, to when Tennyson and many other poets lived there and were inspired by the place. It was the island legacy of these poets, in part, which had persuaded Bob Dylan to perform there the year before. So it seems fitting that the book ends with the words of the poet John Keats, also a resident, summing up the hippy festival ethos, way before his time.

To conclude, it’s a great book, highly recommended, and it’s real triumph is that by the end of it, you don’t just wish you were there. You feel as if you actually were.

Claire Palmer

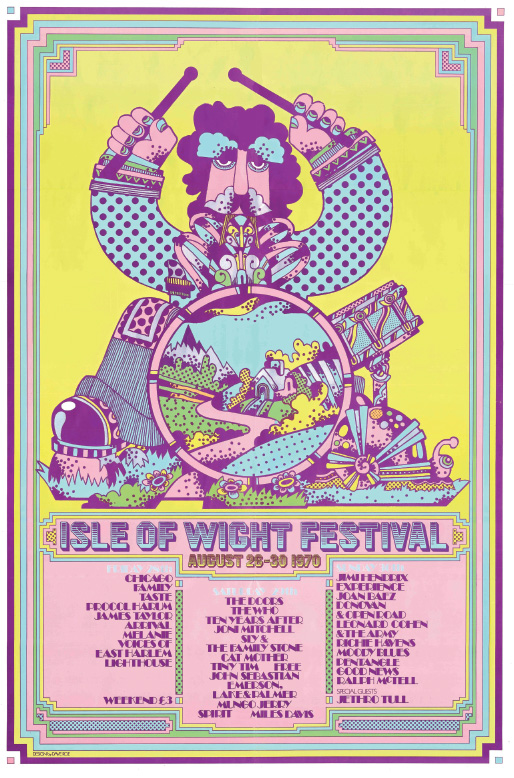

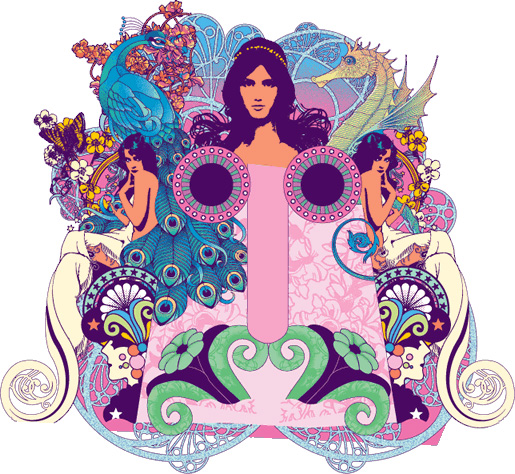

The striking artwork by Dave Roe which gave the festivals their identity

Some of the mainstream press at the time

The Festival Today

Isle of Wight Festival Promoters present and past: John Giddings and Ray Foulk at the festival 2016

Isle of Wight Festival Promoters present and past: John Giddings and Ray Foulk at the festival 2016

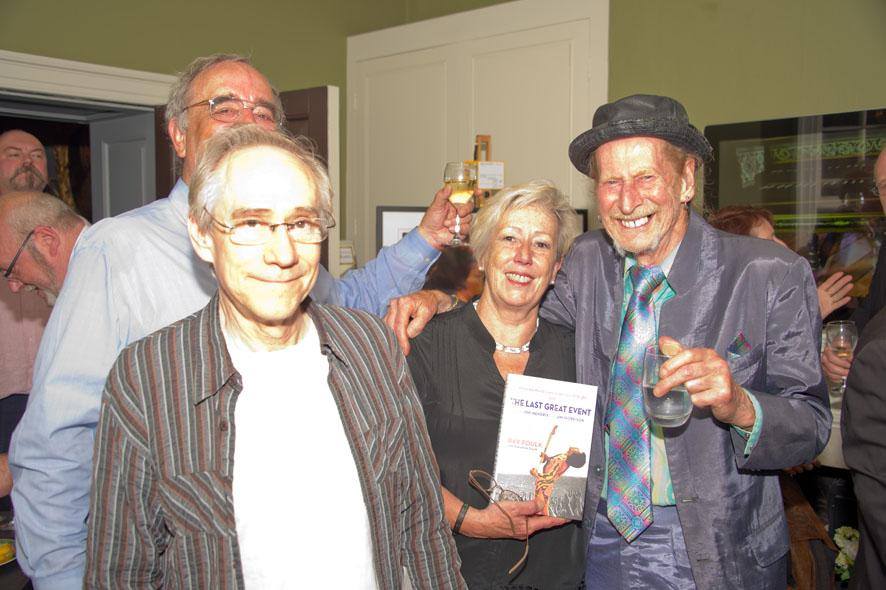

THE LAST GREAT EVENT launch at the Hendrix House museum, London, 7 June.

Ray Foulk with Medina directors Peter Harrigan and Kitty Carruthers and special guest star NIK TURNER.

Caroline Foulk and Ray Foulk with Alabama 3 at this years festival

http://www.redfunnel.co.uk/my-isle-of-wight/blogs/renegades-all-alabama-3-meet-ray-foulk/

Claire Palmer

.

Thanks so much Claire for taking the time and trouble to get to grips with our book and represent it so kindly. I was really touched by this. Thanks again. Missing you as ever.

Comment by Caroline Foulk on 22 June, 2016 at 10:26 amCaroline

You’re welcome Caroline, you did a great job.

Comment by Claire on 22 June, 2016 at 3:16 pmMiss you too

Cx

Fairy Tales and more fabrication, especially for IT

Comment by jeff dexter on 3 May, 2021 at 7:30 pmFeel free to share your own version of events Jeff, or tell why you think it’s a fabrication.

Comment by Editor on 3 May, 2021 at 7:38 pmIn absence of a reply, I’ll add this article which was hot off the press after the festival, for context.

https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/wheeling-and-dealing-on-the-isle-of-wight-70468/

The efforts (and success) in the 1990s to overturn the festival license ban paved the way for the new Isle of Wight Festival, Bestival, and also the Boomtown Festival in Winchester where we decamped to in order to stage a festival on the Matterley Farm site, working in conjunction with the Hat Fair, the UK’s longest running street festival, and the themes, ideas and ideals of which featured in my promotional literature produced at the time.

Comment by Claire on 6 May, 2021 at 6:03 pmI’ve just read your breathless

and generous revue

of the history of the IOW

Fest of 1970

I am v glad

the perceived spirit

of that event survives

in the pages of IT now

but there’s so much to say

about IOW 70

and so much to challenge:

viz Jeff Dexter

I motorcycled

all the way from Sweden

to get to the

opening eve of the Fest

but was so tired

when I arrived

I had a sleep in my tent

never woke up

and missed the opening night

completely

It was the first big fest

I’d ever been to

and arrived especially

to see and hear Miles Davis

tho’ there were

loads of other acts

I liked too

at the time I was writing

unpaid

for the rock mag Zigzag

and wrote it all up

in a subsequent issue

I enjoyed it

wasn’t sorry I went

and had confirmed

what I already knew

that big events are

not my cuppa

Dennis Gould and Pat(ricia) West

the other two members

of RiffRaff Poets

were always

trying to persuade me

to go to Glasto

where they regularly performed

eventually I caved-in

and appeared with them

(I cycled there)

in 1992

I’m not sorry I went

but again it confirmed

what I already knew

and I’ve never been again

so I’ve been to two big Fests

in my life

but know that

as far as I’m concerned

small is beautiful

and I’ve always been

more interested in localism

than internationalism

incidentally

last year a big fat

paperback tome appeared called

Art Anarchy and Apostasy

which is a history of

Better Books in Charing Cross Road

and London counter-culture

of the 60’s – 70s

to our surprise

Dennis and I make

brief appearances in it

but unless I’ve missed something

I’m even more surprised

that it’s not been

reviewed/reported on

in IT

incidentally

at IOW ’70

I was among

the thousands(?)

who fled to the beach

and took part

in the mass skinny–dip

in my case I fled

from the fey meanderings

of Donovan

and instead enjoyed

a spontaneous party

and a memorable

afternoon

I hope Jeff D

sends some memories

of IOW to IT

I’d like to know

his view

{from an email to Claire, published with kind permission}

Comment by Jeff Cloves on 13 May, 2021 at 7:54 pm