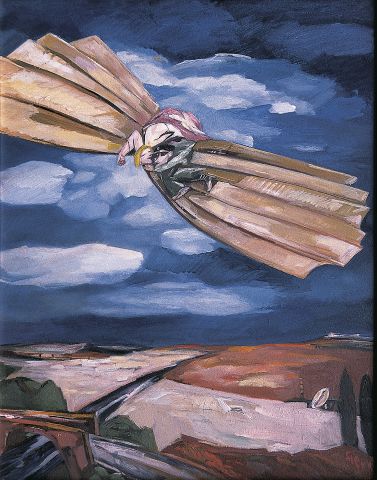

Stanislaw Frenkiel –

Two in Flight – 1988

Synopsis

The story spans a day in November 2010, as the final preparations of a major retrospective of an aging painter are underway at Tate Modern. The private view; a jamboree of press, critics, celebrities and sponsors (even Tony Blair, a friend of the sponsor, is expected) takes place that evening, and the painter, Mateus Stefko, whose life has been blighted by war, secretly plans to make a citizen’s arrest. He becomes attached to a young art handler, Jerome, unaware of Jerome’s past in the care system, and who was helped into art school by Martha, a charismatic art therapist who had strong unconscious feelings for him. As Stefko and Jerome check the final hang, the paintings trigger Stefko’s memories:- pre-war Krakow, POW in the Soviet Union, cosmopolitan Beirut and eventual arrival in the UK. When they reach Untitled, a portrait of a partly dressed, masked woman, Stefko reflects on the intense relationship he had with its subject – Martha – whose hour by hour agonizing about whether to accept Stefko’s invitation to the opening is spliced into the unfolding story at Tate Modern. She hasn’t seen him for thirty years. Jerome’s story meanwhile is told in flashback, with the mysterious Martha at the heart of it. Neither Stefko nor Jerome know of her existence for the other until the denouement that evening in front of Untitled. This private drama is offset by a very public one, as Stefko waits and watches for his prey.

The novella is about how making art can deliver emotional salvation, as well as the relationships between the main characters, and how war has affected their lives. Dedicated to Stanislaw Frenkiel – 1918 – 2002 www.frenkielart.com. This is a fictionalised account of his life but the paintings described in the text and reproduced here are real.

The tale will unfold week by week, through Stefko, Jerome, Martha and the paintings.

.

10am.

Royal Academy of Art

Martha had enjoyed the Glasgow Boys. Good painters most of them, but out of time – theirs and ours, she thinks, wishing she had someone here to say that to, someone she also could fret with about the evening, like a teenager contemplating a difficult date. So, another exhibition under her belt – painting by proxy Matt had called it, Martha wanders into the diffused daylight of the atrium, wondering what all this art consumption amounted to; the looking, standing back, mincing forwards, communing with pigment. Did it store itself somewhere? Make you incrementally a better person? Fitter for friendship? She stares at a faux classical statue. Should I go tonight? But this useless angel has stone eyes.

A whiff of Je Reviens, her mother’s old perfume. Martha turns her head towards an elderly couple looking at postcards. The woman is stocky, wearing a mauve linen jacket, striped tea shirt and mid-calf maroon skirt that has the effect of chopping her shins in half. Her shoes are like pies, her hair short, grey and flat; nothing like her mother, with her bouncy perm, pastel dresses and white cardigans. The man is tall, thin and supported by a stick the same toffee colour as his roomy corduroys. He wears a navy blue fleece, above it a florid kindly face with bushy eyebrows and a cloud of white hair. Ex Bohemians probably, well into their seventies but considered active, full of vitamins, good food, Higher Education and fish oils for their joints. Relics from the days when marriages were worked at, living their late years in cosy boredom with one another. She edges closer, sensing their contentment as they buy a postcard of a painting of geese.

‘This one for Molly and the kids darling?’ asks the man.

‘Lovely Clive.’

Martha, pretending to look at postcards too, is suddenly jealous of this Molly and the assumed grandchildren clustered around an Aga somewhere in the Home Counties.

‘All done, Joycey?’ asks Clive – more a statement than a question.

‘Yes. Coffee?’

‘Lovely.’

Martha feels like a spy as she follows them into the lift. The doors close and they descend in a hush – just the three of them. She wants to wriggle between them, each of her sixty-year-old hands in one of theirs. The lift stops at the first floor. ‘Anything from the big gift shop?’ booms Clive.

‘No, and don’t shout, we’ve already got Molly something’ says Joyce, patting the side of her handbag. Martha mirrors the gesture, patting her bag too, where a letter lies, wrapped around the invitation.

They reach the ground floor and Martha imagines the couple thirty years ago, welcoming their student daughter home at weekends and holidays to chat about her course, cook her roast dinners, send her to bed for early nights curled up in her childhood room with a book. Not for Molly the nerve-racking trips to the nursing home to visit a father sighing out his war memories, holding his hand as he sobbed for his wife. She was my mother Dad, I’m bereaved too. Her mother’s death, just as she was about to start art school was a trauma, leaving her beached with a grieving father who’d lost his mind decades ago, on the Burma railway. She could have done with a Joycey and a Clive.

She follows them through the gloom of the lower tearoom; six legs and a stick. ‘Need the loo, Joycey?’

‘No darling.’

Clive tilts his head.

‘I said no, I’ll be all right.’

As they pick their way through the sparse queue for Treasures from Budapest she remembers Matt kissing her for the first time in here, in front of Ensor’s epic painting Christ’s Entry into Brussels – crowd scenes ever the turn on.

Clive shows his pass to the woman checking membership for the Friends’ Room, who seems to think they are all together. And so they are, as Martha slips through the door behind them, into a murmur of middle class vowels and clinking spoons. Matt used to call it Der Blau Rinse room.

‘Bit of a crowd,’ sigh Clive and Joyce together. Martha stands behind them in the shuffling queue. Fantasies of a milky middle class childhood take hold and she decides to order a hot chocolate. She also wants to lay her head on Clive’s shoulder, fling her arms round Joyce’s waist, get them to tell her what to do. Should I go tonight? Should I tell Matt?

‘What do you want darling?’ asks Joyce

‘Cake.’

Silence.

‘Am I allowed?’

‘Remember your cholesterol,’ says Joyce, wagging a finger.

‘Just a small piece?’ Pleads her husband, raising an eyebrow.

‘Well, I need some roughage, so lets share a fruit cake,’ says

Joyce, tucking her hand into the crook of her husband’s arm in a flourish of happiness. Martha winces at the gesture, thinking of Matt and Eva. Like other cultured eastern Europeans, they’d have been soothed by places like this, fitting in with the English middle-classes after the horrors of the war, hanging on to each other, their education and impeccable manners masking the deep trauma revisited during sobbing jags at three in the morning. Would Matt ever have left Eva? Would he have abandoned the comfortable house in Surrey for her rented bedsit? A nest for a perch?

Clive strains his neck to look for seating, and angles his stick like an eighteenth century dandy, ‘grab that one there darling.’ As Joyce potters off to capture the sofa, Martha decides that Molly is a recovering addict who has had her baby taken away by social workers. Clive loads his tray and Martha orders an Americano. She finds a single seat by the door, and unfolds the letter.

October 20th 2010

Dearest Martha

The Tate let me sneak this note to you without upsetting any data protocols. I hope that you are well. A long time with no see, as you say. I have missed you all of these years and as an old man feel the need for some kind of closures around you. This is what a shrink told me after my wife sent me to him for my inability to sleep. I told him that it was not the arms of Morpheus I wanted but yours. Anyway, he was a genial old Hungarian that I had known for ages, who told me about his mistress too, and then I stopped going. All I need to do is paint, which I do from mornings and most of the night. I am also making etchings and aquatints for another series of winged men. You would like them, especially Two in Flight. Martha – I want to see you again before all the hullabaloos at the Modern Tate. I am exhibiting the last portrait of you, the one where you are wearing the white silk mask and red shoes. Nothing else I grant you, but the angles and perspectives hide your body. No-one can know it is you. I will call it Untitled. I remember being very excited when I painted it and hope that was not what scared you away. I recall that you were enjoying yourself too. Please let me see you again. After almost thirty years I still think about you and why you left so all of a sudden.

Are Es vee pee, as they say.

Love Matt

Martha refolds the letter around the invitation and returns it to her bag where it lay like a depth charge. Maybe I should just stay away, keep the peace. ‘But it’s not peace is it?’ She says aloud, watching Clive and Joyce, attack their cake like greedy birds. And besides, he should know. I should tell him.

Jan Woolf

Untitled: a novella is being serialised each week on International Times

http://internationaltimes.it/untitled-novel-part-one/

http://internationaltimes.it/untitled-a-novela-by-jan-woolf-2/

http://internationaltimes.it/untitled-a-novella-by-jan-woolf-3/