Republic of Frestonia: How squatters in a 1970s London street declared independence from the UK

The Free Independent Republic of Frestonia was born of a generation who knew counterculture as much as precarious living. Now a new book collects photography and stories from the community

There was a lot of talk, in the wake of the Brexit referendum, suggesting that London should stage its own exit from the United Kingdom, declare independence, and ask to rejoin the EU as a nation state.

Ignoring for now the fact that not everyone – though it might seem that way to London – outside the capital voted to leave the EU, it seemed a satisfying, though jokey, postscript to the Brexit vote. Indeed, more than 180,000 Londoners signed an online petition calling for the mayor, Sadiq Khan, to “declare London independent, and apply to join the EU – including membership of the Schengen zone”.

But what a lot of the signatories might not have realised was that there was indeed a precedent for London seceding from the UK. Or at least, one street of the capital.

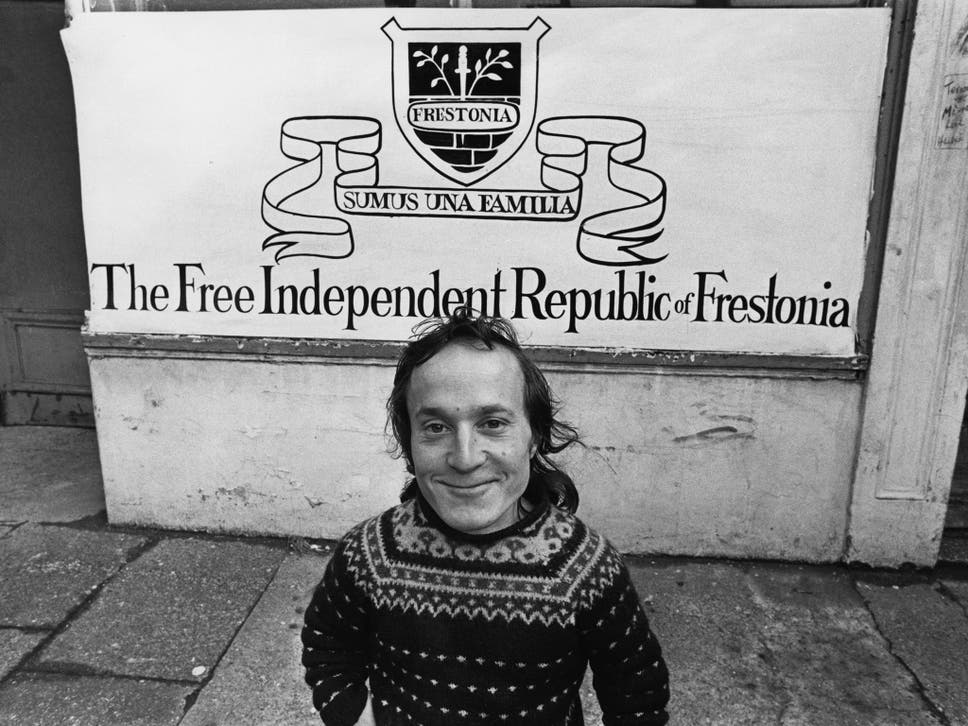

Welcome to the Free Independent Republic of Frestonia. Or, what’s left of it, which these days amounts to the Frestonian Gallery, keeping the name and spirit alive of one of the most curious episodes in London’s history. It began on Halloween 1977, when the residents of Freston Road in Notting Dale, West London, which was largely comprised of squats and communes, declared independence.

Threatened with eviction, the squatters said they were no longer part of the UK and appealed to the United Nations to send in peacekeeping forces to prevent Greater London Council turfing them out of the homes they had claimed. They designed a flag, appointed ministers of state, and even made their own postage stamps and issued visas for visitors.

The short-lived story of the Free Independent Republic of Frestonia has now been documented in a new book of photographs by one of its residents, the photographer Tony Sleep, who was resident on Freston Road from 1974.

Sleep describes the Frestonia experiment as “part publicity stunt, part theatrical protest”, and adds that while it wasn’t a serious attempt to break away from the UK, there was never any need to, because what became Frestonia “was already on a different planet”.

He writes in the lavish book: “Frestonia was rooted in the counterculture of the time. The period is now dismissed as little more than daft clothes and hair, accompanied by a great soundtrack and the invention of sex and drugs.

“It was, we are told, youthful self indulgence that ended badly because it was irresponsible and naive.”

Frestonia was born out of problems that young people will recognise today: the lack of affordable accommodation. Sleep points out that the millennial generation might have a beef with the baby boomers who grew up in the 1960s and 1970s because they had it easy, and accommodation was cheap and plentiful. Not a bit of it, he says.

“Rented flats were in very short supply, and mostly slum standard. You might achieve a rented bedsit as long as you weren’t black, Irish or a dog. Then, as now, landlords wanted ‘professional’ people.

“Council housing lists were only for families, and backlogged for decades. Despite what now seem like absurdly low prices, only the wealthy and secure could obtain mortgages at a time before easy mass debts. Less than half the population owned their own homes at the start of the 1970s.”

Many of the houses on Freston Road were empty, having been condemned as unfit for human habitation, and most of the residents had been relocated to the new highrise blocks of flats that began to go up in the 1960s and 1970s. There had been a move to demolish the vacant properties, but residents in neighbouring communities had complained that they would be looking out onto swathes of barren, rubble-strewn land that would encourage flytipping, so the authorities decided to take the cheaper option and just leave the buildings standing for a while.

Freston Road might have been abandoned, but that didn’t mean it was unused. From 1974, squatters began to break into the empty houses and set up home there; Tony Sleep, aged 24 at that time, was one of them.

He recalls: “Squatting is distinctly equal opportunity. If you can gain possession, it’s yours. This led to an interesting mix of people who had little in common except needing somewhere to live and being poor for one reason or another. While some tried to make their new homes habitable, several houses were quickly wrecked.”

Sleep remembers well his first sight of Freston Road. He’d been living in a “dismal rented basement” in west Kensington, but as he and his girlfriend parted company, he needed somewhere else to live, and heard about a street of empty houses. Some of his friends went to have a look and broke into two of the houses.

“That night I paid them a visit,” writes Sleep. “Eight people, four guys, four girls, in one candlelit room, the only one that had windows. There was no toilet, no water, no electricity.”

But his friends set to work installing plumbing and wiring as best they could, found an old toilet, rescued carpets and furniture from skips, and Sleep asked if he could move in with them.

By 1977 Freston Road had settled into an unorthodox community, of sorts. But the attention of the GLC wandered back to these old, abandoned homes, and the squatters were told that they were to be evicted from these properties.

The council offered to place the squatters in what were considered “hard to let” properties dotted around London, and some took the flats – and, says Sleep, were promptly replaced in Freston Road by other people desperate for somewhere to live.

The GLC announced its intention to bulldoze Freston Road after all, and a meeting was called, attended by 200 people. They decided – inspired by the Ealing comedy Passport to Pimlico – to go it alone. The Free Independent Republic of Frestonia was born. And the battle was on.

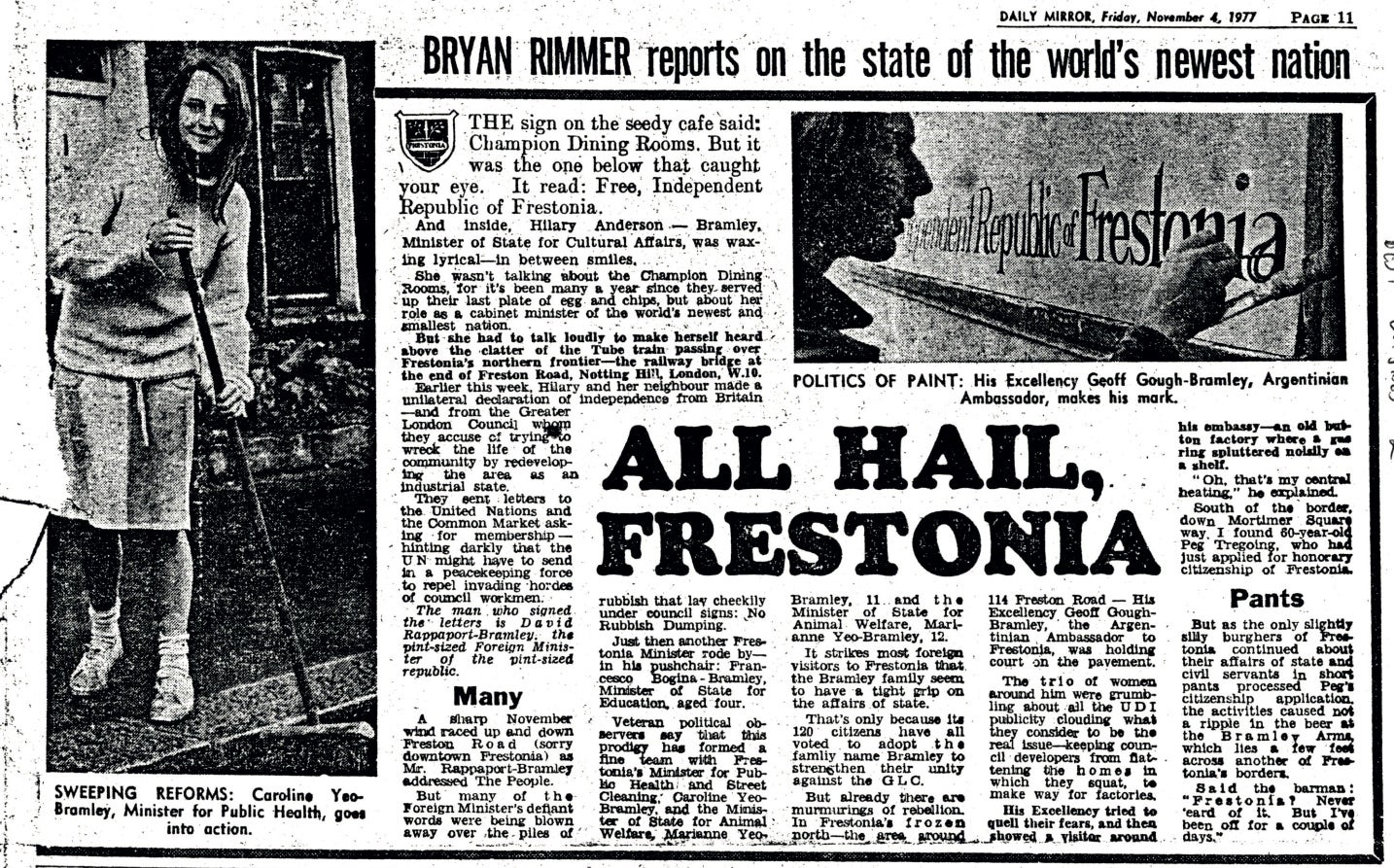

The Frestonian National Anthem was written (“Long live Frestonia! Land of the free – not the GLC”) and a community newspaper, The Tribal Messenger, was distributed. Frestonia made the international press, and the Daily Mirror ran a piece declaring “All Hall, Frestonia”. The actor David Rappaport was made foreign minister, and playwright Heathcote Williams became ambassador to the United Kingdom.

It was all a bit jolly and, of course, more than a pinch of Ealing comedy. But, Sleep points out, Frestonia was also an interesting way of putting British society under the microscope.

“Communities are defined, more or less, by what people have in common,” he writes. “That’s usually class, background or aspiration, sometimes race or religion. What people have in common helps them feel safe and valued. What is different can be threatening or divisive.

“Families, on the other hand, are a matter of being stuck with people you sometimes struggle to tolerate, let alone like. Frestonia was a bit of both.

“Frestonians were, beneath the veneer of pragmatic anarchy, from different cultures. There were the hippies, idealists of a sort. There were the punks, nihilists of a sort. And there were the itinerant street people, whose lack of youth and lost changes gave them a thread of bitterness to chew on together.”

Over the next couple of years, fighting the threat of the GLC bulldozers, the anarchic squat collective organised itself more seriously, forming the Bramley Housing Cooperative with an aim that was less about the fun of independence and more about securing the future of the Freston Road community.

Eventually, the GLC won the war, and demolition of the squats began in 1983. But the Bramley Housing Cooperative, working with the Notting Hill Housing Trust, continued to fight for Freston Road as a residential area. And, ultimately, they won.

Sleep says, “Frestonia didn’t cease when the squats were demolished. How could it? They were only useful ruins. Frestonia was about the people, its improbable family.

“If you walk through Frestonia now, there’s little to suggest it is much different from anywhere else. You’ll find a street of small, but perhaps unusually pretty houses, built in the mid 1980s. They look carefully designed, a bit too individual to be social housing. You may not notice the enclosed communal gardens, or the sheltered housing scheme that the coop insisted on, you won’t know the coop ensured housing for some of the more vulnerable Frestonians.”

It might be that Frestonia would be forgotten all together, but for Tony Sleep’s photographic record of the people, events and houses on Freston Road in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

The name does linger on in the form of the Frestonian Gallery, opened in 2017 by Matt Incledon and Rollo Campbell, who have published Tony Sleep’s photographs and recollections in Welcome To Frestonia. A pair of, in their own words, “itinerant art dealers”, they opened the gallery in The People’s Hall, a Victorian building that was once at the heart of Frestonia.

Becoming appraised of the story of Frestonia, they were introduced to Tony Sleep, and arranged an exhibition of his photographs. They write in their foreword: “It was an exhibition unlike anything either of us had worked on previously. Each day at the gallery provided a steady stream of visitors keen to revisit and share their own personal memories of Frestonia. It would be a nice point at which to say ‘We then decided a book of Tony’s work needs to be published…’ but again, in truth, the decision had been made for us already by the sheer emotional response to this unique exhibition.”

Was it all worth it for the Frestonians? Did it make a difference? Tony Sleep closes his remarkable document of this time by musing, “Forty years on, the UK seems to have travelled in a large circle and arrived little the wiser, but probably angrier, more cynical and more divided than ever. We are all Frestonians, on this small blue dot in the middle of nowhere. We are all one family, whether we like it or not.”

Welcome to Frestonia by Tony Sleep is published by the Frestonian Gallery (frestoniangallery.com), priced £35