Richard Smith Artworks 1956-2016 (Estate of Francis Bacon/Thames & Hudson)

David Smith: The Art and Life of a Transformational Sculptor, Michael Brenson

(Farrar, Strauss & Giroux)

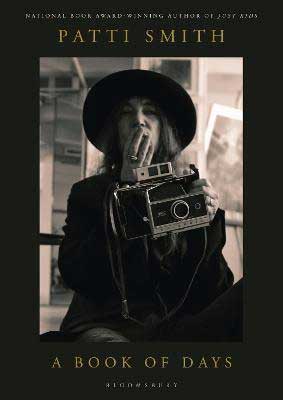

A Book of Days, Patti Smith (Bloomsbury)

The painter Richard Smith has been on my radar, and his catalogues on my bookshelves, for many years now, but I’d always mistakenly assumed that he was a minor artist in the grand scheme of things. I guess the fact one of the catalogues was from the Tate should have flagged up that he was more well known, or had been. The arrival of this beautiful new monograph offers clear correction to my ignorance, and finally offers up a career overview and some critical context and discussion.

Smith is and was best known for shaped canvasses, sometimes associated with Pop Art (more I suspect from his colour palette than the shapes) and what have come to be known as kites, a term the artist was not keen on. Later on he would use more regular canvasses to paint loosely geometric paintings that were often interrupted by intervening colours, shapes and forms, in much the same way that structural bamboos gridded the kite paintings, and that the curves and edges of his shaped canvasses did.

As early as 1968, when discussing ‘The shift in emphasis to where the 3D property of the painting became more the subject’, he noted that ‘The making of paintings has always been a subject in my work’ and that ‘The shape is an aspect of colour, the distortion of the canvas membrane alters the way the colour can be seen’. He wanted to use colour, he said, ‘to make a dense glow, to make a light that cannot be switched off/on’, which informs Chris Stephens’ suggestion that in effect ‘These were now paintings concerned with exploring their own basic components’, that is self-referential and self-sufficient, as much about their making as what is made or seen by a viewer.

Smith’s concern with shape as a device to change colour was somewhat at odds with the then prevalent critical concerns of the likes of Clement Greenberg who demanded that painting be about flatness and surface and paint itself as much as colour. Smith rejected this and started looking outwards to other forms of abstraction happening at the time, especially minimalism and the more gestural abstract work of the St Ives artists. Minimalism is certainly present in the grids present in his work from the 70s, as well as the aesthetic of the kites, which also play with the idea of minimalist perfection by using string or ribbon ties to hold the work together.

Some of the kites were wall pieces but many became intriguing hanging sculptures, sometimes hung in groups of similar variations. Later wall-hung kites, such as 1986’s ‘The Typographer’, assembled smaller kites into a more complex arrangement of planes, forms and colour, busy and dynamic work that keeps the eye moving across and into itself. They are somewhat reminiscent of Frank Stella’s later work, but the kites are in marked contrast to his literally and metaphorically ‘heavier’ constructions, just as some of his shaped and more monochrome canvasses such as ‘Clairol Wall’ (1967) are as dissimilar to as much as reminiscent of Ellsworth Kelly’s work.

What the catalogue perhaps most highlights is the fact that Richard Smith was consistently a painter. Early work such as looser and thinner ‘Product’ (1962), the angled colour forms of a shaped canvas such as ‘Fieldcrest’ from 1969, and many of the kite works, evidence a continuous trajectory towards the later abstract geometric work on canvas and paper. One of the kites is even titled ‘Thin Painting’. It seems that Smith realised that paint itself could do the work he had delegated to sculptural surfaces and hanging structures. Works such as ‘Surface 1’, ‘Tricorne’ and ‘Notes’, all from 2009 are startling in their dynamic use of colour, gesture, pattern and form. The colours sing out loud and clear, just as other 1990s works on paper use a snaking line to interrupt and weave through and between wet stripes and grids, with drips and slurs of colour adding to the visual energy.

As well as pictures of his work, this beautiful volume also contains four essays offering interpretations and contexts of his work, sketches, photographs of Smith at work, and a wonderful set of black and white snapshots from his 1975 Tate Retrospective. I hope this long overdue monograph will help rescue Richard Smith from obscurity and allow a new generation of readers and artists to discover his work.

The sculptor David Smith has remained well known since his death, with David Smith by David Smith remaining a hugely popular, best-selling book. Its oversize square format showcases his late sculptures arranged in the fields where he lived, contains a provocative set of questions still invaluable to art students, and offers a glimpse of his spray-paintings, workshops and working methods. It’s a bright and colourful, engaging collection, full of energy and work-ethic, innovation and experiment. I’ve had my own copy since the early 80s after coming across the book in my art college library.

In his lifetime, Smith revolutionised sculpture. He combined down-to-earth metalwork skills with artistic vision, welding together found and made objects after laying them out on his studio floor, or sketching them out in spray paint silhouettes and gutsy drawings. His early work was a kind of hieroglyphic or imagistic three-dimensional writing in metal, whilst later work centred on oversized assemblages of painted steel forms, or scratched and polished stainless steel which caught the light from every angle.

He never lost his work ethic, and although he partied and drank hard with many of the New York crowd (and also drank hard when by himself) and could throw great parties – dinner or otherwise, he was at heart a loner who spoke his mind and often upset people. His marriages and relationships did not last, and he ended up – by choice – living in the sticks of Bolton Landing, where property was cheap, and if he wanted to he could still drive to NYC. It was at Bolton Landing he laid out grids of concrete bases he could bolt his work to, his own outdoor exhibition space next to his studio, workshop, house and stored piles of materials.

After a residency in Italy, where he astonished the workers and residency organisers by producing a huge number of sculptures in the abandoned works in Voltri he had been offered as a studio, he shipped other gathered material back to the USA and once home himself continued to work hard there. He was famous, critically established, and had sold enough work to feel wealthy. But there were other things in his life beyond art, as Michael Brenson makes clear in his new biography. Ex-wives and girlfriends, cigars, alcohol, friends, rivals, enemies and acquaintances all feature, although thankfully Benson insists upon Smith’s art being the focus of the book. It’s detailed, factual and highly readable, but it also raises the spectre of Smith as an alcohol-fuelled womaniser, not afraid to use his fame to sleep with students who came to help him make work. He clearly never lost his love for his children, and he spent as much time with them as possible, but there is a sense of dysfunction and obsession, that clichéd single-mindedness and egotism that some argue genius requires.

On the evidence Brenson presents, I don’t think I’d have liked Smith very much, but I do love his late sculpture and those fields full of his work documented in photos of the Bolton Landing. I guess it reminds me, once again, that it’s the work that actually matters, not the artist or writer; but that’s my problem, not Brenson’s, who has produced a detailed, informed and highly readable true story about David Smith.

Patti Smith is my favourite Smith of the three under review here. Her version of New York punk, inspired by poetry along with artistic assuredness and feminist attitude as much as music, produced the astonishing Horses album and led to other great albums such as Easter as well as a number of books of poetry/lyrics, memoir and reflection. A Book of Days is somewhat different, as it offers up 366 images – one for each day of a leap year – with a brief caption below. Some photographs are reprinted from Smith’s Instagram account, a few are by others, all offer a personal insight into Smith’s world.

Many of them are of Smith’s heroes and inspirations, from Martin Luther King to Kurt Cobain, others are friends and inspirations such as William Burroughs, Lenny Kaye and Flea. Smith’s family and pets appear too, as well as travel snapshots from her tours and journeys around the world: the red sunlit rock of Uluru, the statue of Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, the Atomic Bomb Dome in Hiroshima. There are art objects too, such as Joseph Beuys’ felt suit and a bust of Apollo in a Moscow museum, but mostly there are photos related to Smith’s life and influences.

It is here however, one feels a sense of constructed self. Sure, the discarded worn-out cowboy boots and disorganized bookshelves; yes, the childhood snapshots, images of guitars and friends like Lou Reed and Tom Verlaine, but the hipster fixations seem more questionable, a bit of an adolescent hangover. Let me offer up a list as evidence: Rimbaud, Artaud, Sylvia Plath, Camus, Virginia Woolf, Gérard de Neval, Joan of Arc, Apollinaire, Tarkovsky, Shelley, Lovecraft, Simone Weil, Jim Morrison… and Joan Didion. Didion wouldn’t, I suspect be impressed by all of the company she keeps here, or by the far too many slightly-out-of-focus shots of graves, cherubs, statues, icons and churches.

I don’t want to diss that list above (though I’ve got little time for Plath’s, Lovecrafts’s or Woolf’s writing), indeed I think Artaud and Joan Didion are exemplary, and Jim Morrison highly entertaining when I’m in the mood for drunken shamanistic posturing (him not me). But I prefer the more recent photos of Notre Dame, post-fire, and 9/11 rubble, along with references to Samuel Beckett, Ginsberg, Hendrix, Frank Zappa and Rutger Hauer as Roy Batty in Bladerunner. These seem more contemporary and relevant, not part of an artistic attitude or pose.

We all know writers, musicians and artists need a public face as well as a private one, we’re all sucked into nonsensical and irrelevant questions about whether things are ‘true’ or not, and Patti Smith is certainly a strong, assertive and honest troubadour and author, but this book doesn’t feel right. It feels mannered and awkward whilst attempting to be precious and open-hearted, sharing secrets and dreams. Maybe it’s simply too much at once, gathered together rather than delivered through the daily drip-feed of Instagram, or maybe I don’t share all the same heroes or Smith’s somewhat mystical ideas about creativity. Whatever it is, it had me reaching for my copy of Babel and pulling my early Patti Smith albums out instead.

Rupert Loydell

At least the positive is that you pulled out your Patti Smith albums, always a worthwile thing to do.

Comment by Tom Wiersma on 28 November, 2022 at 4:21 pmI’ve just picked up my copy of Book of Days, so too early to opine, but I may get back to you about it once ingested 😉

And now I’m back after a pleasant evening of reading A Book of Days, to comment that it is Instagram in print. Without the likes and external noise. A tad self indulgent at times, but never the less a very “lookable” set of images. Glad the book is in my collection.

Comment by Tom Wiersma on 28 November, 2022 at 10:05 pm