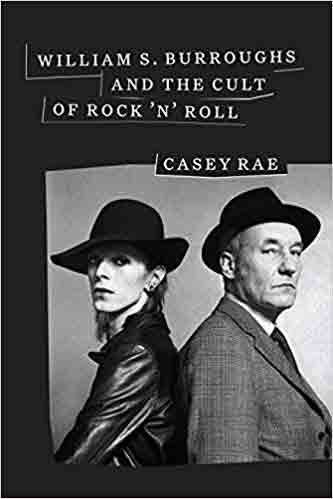

William S. Burroughs & the Cult of Rock’n’Roll, Casey Rae (University of Texas Press)

Casey Rae appears in awe of William Burroughs, and from the very start of this book is prone to making sweeping assertions such as ‘It’s hard to imagine sample- and remix-based music without Burroughs’. It’s easy to get caught up by her enthusiasm and argument, but a little slowing down reveals the flaws in her argument. Burroughs did not invent the cut-up or collage, and in fact it was artist Brion Gysin who suggested to his friend Burroughs that he should try using some visual arts techniques such as collage in his work; the Surrealists and Dadaticians had used random collage, automatic writing and cut-ups decades before. Sample-based music may draw on these ideas, but was dependent on the invention of the sampler following music’s move to the digital. Burroughs may have acted as a populiser of cut-ups, through the mass sales of his early novels in the 60s and 70s, but Rae overstates the case.

As indeed, she does throughout most of her 293 pages. Although in her ‘Introduction’ Rae claims that ‘[i]f this were just a collection of vignettes of Burroughs hanging out with rock stars, it would be plenty entertaining. But there is much more to the story’, I struggled to find this ‘much more’ or be entertained. I’m a big fan of Burroughs’ writing, especially the later novels where he is more in control of his work, and I like much of the music discussed here, but I’m not as uncritical as Rae, nor convinced that Burroughs was the centre of all the activity she describes.

According to Rae, Led Zeppelin, Bowie, Genesis P-Orridge and his various bands, the Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, Laurie Anderson, Lou Reed, Soft Machine, U2, Tom Waits, Coil, Kurt Cobain and Nirvana, Sonic Youth, Patti Smith, and even Bob Dylan and Paul McCartney are part of some huge Burroughs-inspired brand of music. I’m sure they’ve all mentioned him, read him, some even met and worked with him, but Rae’s work is full of hyperbole, exaggeration and conjecture. So we get over-excited sentences like this:

The most intrepid creators and thinkers – people like Burroughs and Dylan – continually seek new vistas, different ways of being that can be expressed to others in the form of possibility. (p63)

or the understatement and banality of ‘[t]he relentless pace of the Information Age has posed challenges for creators. The old gatekeepers are still there, and now there are new ones […]’.

There is little critical engagement with the material here, what we basically get is a(nother) Burroughs biography with a focus on the musicians he bumps into or is around, with lots of recycled material from other sources, filtered through a messianic reverence and adulation. Rae comes on like a weird vicar at the conclusion of the book:

William Burroughs remains in the hearts of those who knew him best […]. Those who know only the icon have the opportunity to become better acquainted by delving into Burroughs’ voluminous body of work. In doing so, we may also discover something of ourselves–our fears, desires, longings, aversions, and hopes for the future. (p267)

As Rae also says on her final page: ‘Burroughs writing, interviews, recordings, performances and paintings will live on’. This is, however, despite and not because of sycophantic books like this.