by

ANDREW DARLINGTON

‘The Music That Thrilled The World… And The Killing That Stunned It!!!’

Altamont was the bloody slash that transformed a decade’s dream into disillusion.

For the Rolling Stones, it was meant to be ‘Woodstock West’. It became an atrocity.

This is the end, beautiful friend. The end of the innocence. Perhaps it’s the time of

season, maybe it’s the time of man, but astrologically-speaking,

voodoo-wise it’s sheer Satan. Andrew Darlington tells the tale…

‘A PUBLIC EXECUTION…’

‘when the blitzkrieg raged, and the bodies stank…’

(Rolling Stones, ‘Sympathy For The Devil’)

Hot-Hot Heat. An abrupt rise in the mercury – 451 Fahrenheit, at least. A thumping in my head like it has to be… a heatwave howling through my veins, a hurricane whirling in my head, my cool disposition hanging by a thread, is it a question of love – huh? Is it a state of mind…? No – hey, far out… looks like I’ve picked the wrong week to give up on acid.

When the Sex Pistols finally bust wide open John Lydon pronounced the end of the ‘Rolling Stones of the Eighties’. Wrong. The Rolling Stones are the Rolling Stones of the eighties. The nineties. And now. A phenomenon – just like an eclipse, an earthquake, or a tidal wave. Something that occurs naturally, has the potential to transfigure lives, but which remains imprecise and defies literal encapsulation. Music comes into it tangentially. Their mythology, longevity, and importance is – in this sense, a phenomenon, but not simply a musical one. The Stones, interviewed prior to this event, are asked ‘are you any more satisfied now than you were before?’ Jagger sneers immaculate contempt, ‘sexually, yes more satisfied now. Financially, dissatisfied. Philosophically, trying.’

The freak-flags fly. Long pennants curl and uncoil. There’s trash-strewn dry straw-grass underfoot. Grit-slopes climb to the horizon. Girls in mauve-tinted shades. Freaks wear tinsel facial-stars. Flabby bare burger-arses wobble and quiver. Blood and abrasions, already. A girl with a bucket solicits contributions for the ‘Panther Defence Funds’. VW Camper vans park in chevron formation, as slow city-traffic crawls along the concrete overpass visible over there. People say ‘hey, I can dig that, man’ or ‘that’d be groovy’. Ike & Tina Turner are on-stage. She does a lascivious cover of Otis Redding’s “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long”. Then a two-way seduction-dialogue with Ike, ‘cos you’ve got what I want’ as she penis-fingers the mic, ‘and I want you to… give it to me’, eye-watering fellatio-coaxing it to a wet-dream orgasm, moaning like the soundtrack to a hard-core DVD. To those who only ever saw Tina at her ‘Simply The Best’ period, this younger slut-sexy incarnation is a total revelation. Then the Flying Burrito’s nimble-picking down-home country-rock, ex-Byrd Chris Hillman, ‘Grievous Angel’ Gram Parsons. In the audience pool-cues flail in squalls and flurries of violence. ‘Please you people, stop hurting each other, you don’t have to’ he begs after they speed-dash through “Six Days On The Road”. There’s an appeal for a doctor ‘under the left-hand scaffold.’ This ain’t Rock ‘n’ Roll, it’s genocide, but I like it…

I wasn’t at Altamont. And it’s difficult to re-occupy that mindset now. Just as it’s difficult now to re-occupy the mind-set of the guy who yelled ‘Judas’ at the electric Bob Dylan at Manchester ‘Free Trade Hall’. But Folk was sacred. The Folk-artists of the time would refer to the Childe number and the Cecil Sharpe derivation to authenticate their source. Yet Dylan achieved his authenticity by assuming other identities, by becoming Woody Guthrie, Dave Van Ronk or Robert Johnson. The Stones too. Authenticity was a big deal. It was a hang-over from Trad Jazz. An inherited puritan pass-down from the likes of 1950s Ken Colyer whose extreme adhesion to replicating the Storyville 1920s became a totalitarian mission for sonic purity. An authenticity artificially constructed through the conduit of hoarded 78-rpm’s. The Stones, via Cyril Davies and Alexis Korner, operated on the same quest for integrity. Across Britain, white boys on the Thames – or the Mersey, or the Tyne, seek out and replicate the Blues, the more obscure the better, but a consensus repertoire runs from the Chess label, the god-like genius of Muddy Waters, Chuck ‘n’ Bo, the awesome Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker, Robert Johnson, Elmore James. In an increasingly synthetic consumer-world it represents truth, roots, the sniff of the real, the grit of ethnic values, of low-cost sweat and blood virtues. Clapton iconically turns his back on the overly-commercial Yardbirds for the more austere John Mayall. Long John Baldry – hitless, but more pristinely pure by being untainted by crass Pop, is vindicated in publicly mocking the Pop-shallowness of the Small Faces’ no.1 “Sha-La-La-La-Lee”. They know it too. “Little Red Rooster” – the Stones last no.1 cover, is a unique event in being both a hit single, and the nearest-close Blues approximation to ever aspire to such commercial heights.

Me, I’ve seen the Stones now in each of their evolutionary phases. I saw them play to two-hundred at Bridlington Spa Theatre circa ’64 with Brian Jones, intense anarchic art-school R&B, elitist, purist, the anger of frustrated energy screwed down tight, raw and violent with a loutish sexuality and an amphetamine burn of painful amplification. While the world – and America, was still in thrall to what Jerry Lee Lewis derisively called ‘The Three Bobby’s’ – Vinton, Rydell and Vee, Mick ‘n’ Keef, and a select few others (on the Tyne, the Mersey) were perceptive enough to seek out the luminous greatness of Chess and attempt to replicate it in Croydon. I also saw them a decade later, back at Leeds University when Mick Taylor had already etched his vibrant block-chords onto their ‘Kings of the Underground’ albums, from ‘Sticky Fingers’ (April 1971) to ‘Exile On Main Street’ (May 1972). Then they seemed cynical, demonic, menacingly depraved, narcissistically narcotic, dangerously decadent. Jagger’s exaggerated choreography, which now seems a comic cliché, was still radiating an aura of unpredictable and salacious menace.

And then I saw them again in 1982. I wasn’t at Altamont. But I was at Leeds’ Roundhay Park. SF writer Harry Harrison once guesstimated that if everyone alive on this planet were to stand heel-to-toe they’d cover an area equal to the island of Zanzibar. That might look rather like Roundhay Park looks now. I spend the entire support sets sat in a miles-long auto-tailback breathing lead-impregnated air caught up in this human avalanche converging on this place, and yet, taking it all in – yes, it’s an impressive gathering – but oddly so. Like that version of some ‘Stand On Zanzibar’-future this is a mass of largely clean, polite, deodorised, civilised, so respectable people. The fashion dummy weirdo count is low. A token sprinkling of Mohican ‘n’ leathers, a small percentage joints, long ratty hair ‘n’ granny-glasses, but the majority are passively non-denominational. Some nubiles and not-so-nubiles in very little clothes prompt sexist reactions very inappropriate to such a Family outing atmosphere. I get inside the Press Cage patrolled by Security gorilla’s, rumour thereabouts is Jagger ain’t arrived, others say he’s backstage playing table-tennis with Jimmy Savile. Five ruthlessly efficient rent-a-thug pass-checks discourage me from questing out either way. This is no Altamont. These are different days. I’m no schoolboy but I know what I like…

‘Far out’ says Jagger, wrapped in long red scarf, topped by a Stars & Stripes ‘Uncle Sam’ top hat.

When the Beatles first get to America they were amazed to discover multiple mop-top copyists. In fact the Knickerbockers’ “Lies” is still the great lost Merseybeat hit, a more accurate clone than Oasis, the Rutles, or even the Bootleg Beatles (and if they ever need a hit single of their own, then here it is!!!). But Stones-alikes are even more legion, from the mighty Chocolate Watch Band on down. With Brian Jones as lead template, fringe, vacant glue-sniffer grin and dysfunctional nod-out brain-deadness. But while archivists hoard rare one-off garage-punk curios by neglected or downright forgotten acid casualties – the more obscure and bratty the better, the Stones splurged out a series of classic singles, any one of which would have guaranteed them junkyard angel status among collectors, if only they hadn’t been by the Stones. Familiarity blinds.

Manager Andrew ‘Loog’ Oldham contrived them into the contra-Beatles. And it worked. An image that had accumulating down-sides. When police, acting on a tip-off from a ‘News Of The World’ snitch, raided Keith’s Sussex mansion, George Harrison was there too, but the Narc squad discretely wait for him to leave before making their move. The public love the Fabs. But unlike the Beatles, the Stones are too rough and ready, too dark and edgy to be truly subsumed into the nation’s collective consciousness. The Narcs are out to get Rock ‘n’ Roll’s bad boys. And sure enough, substances were there to find, plus Marianne Faithful ‘undressed’ beneath her fur rug. Sunday night. Mick and Keith – both twenty-three years old, spend the night in the cells, and pull sentences of – Mick, three months in Brixton and Keith – a year in Wormwood Scrubs. Richard Hamilton’s Pop-Art painting of a hand-cuffed Jagger in the back of a cab after the swingeing sentence for possession – like the song they wrote for Vashti Bunyan, “Some Things Just Stick In Your Mind”. Their convictions soon get quashed, thanks largely to William Rees-Mogg’s (‘The Times’ editor from 1967 to 1981) celebrated editorial about ‘Who breaks a butterfly on a wheel?’ – ‘something I’ll always remember and be grateful for’ admits Jagger many years later. Of course, they got off on a technicality. Drugs were hardly absent from their lifestyle. Rees-Mogg was merely advocating tolerance and equality under the law, even for snotty Rock stars, against those establishment figures determined to ‘teach the louts a lesson’. And lessons were drawn.

Marianne was the daughter of a British military officer and Viennese baroness. She’d begun her career as a coffee-house Folk singer in 1964, before being spotted at a Rolling Stones launch party by Oldham, who co-wrote her first single “As Tears Go By” with Jagger & Richard. A string of hit singles – “This Little Bird”, “Summer Nights”, “Come And Stay With Me”, was followed by society scandal and heroin addiction, but her influence as the Stones’ ‘concubine’ during this most potent period was crucial. She co-wrote “Sister Morphine” and introduced Jagger to Mikhail Bulgakov’s Russian novel ‘The Master And Margarita’ (first published in English in 1967). The book became the primary inspiration for “Sympathy For The Devil”, Jagger’s finest lyric. The Stones 2008 movie ‘Shine A Light’ includes a flashback of the time. Jagger, newly released from jail, is whisked by helicopter to a country house to discuss youth, anarchy and social change with a leading Jesuit, Bishop John Robinson – author of a book called ‘Honest To God’ (1963), and that same William Rees-Mogg. As film-critic Philip French muses, ‘my parents and their friends thought the Stones represented the end of civilisation as they knew it. Maybe they were right.’

6 December 1969. It’s the closing of the Stones sixth US tour. Their first US tour in three years. Three vital years that have changed everything. 1966 was screaming teenybopperisation. Now it’s different. Maturation…? Perhaps. But some kind of culmination anyway. Their ‘Let It Bleed’ (December 1969) is still a top three album both sides of the Atlantic. Altamont is a speedway in northern California, nearest to Livermore. It’s targeted to host an event both intended as the ‘Woodstock West’, and an American version of the London Hyde Park Free Concert in the recent July. Rock made by outsiders, for outsiders. A wild nobility. A ragged aristocracy.

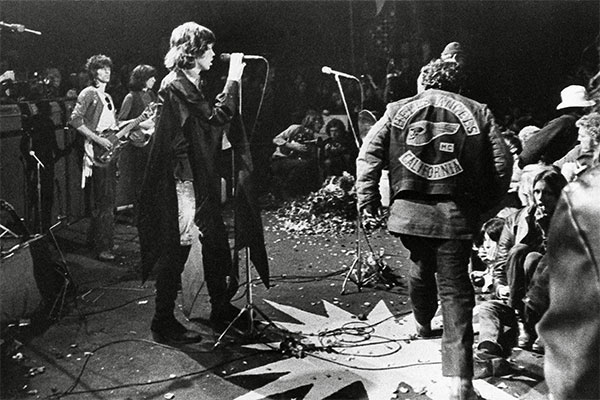

The Stones scruffy hearts aren’t really totally into the ‘Love Generation’ thing. Altamont is free, with The Grateful Dead, Santana, Crosby Stills & Nash, The Flying Burrito Brothers, and Jefferson Airplane, it attracts some 300,000, not all of whom get home safely, or at all. If ‘Woodstock’ was the flowering, ‘Altamont’ is the decay. The Charles Manson death-trip event. The original intended site was the San Fran Golden Gate Park, scene of many previous free concerts, but there were permit-problems. Then the Sears Point Raceway, but again there are hassles, this time over movie-rights, with owners ‘Sears Point Filmways Inc’. Finally, Altamont, only days before the get-go, with a constricted time-frame that messes up stuff like portable toilets and med tents. Both lacking. But – against the odds, shit comes together. Sure, the stage is just four feet above the grit, and is hemmed in by Hells Angels, hired by Stones’ fixer Sam Cutler for $500 and free booze. Hey, they’re counter-culture. Can’t trust the piggies, as George Harrison says, ‘in their lives there’s something lacking, what they need’s a damn-good whacking.’ ‘Woodstock’ had also relied on u/g policing, the Hog Farm hippie commune led by Wavy Gravy. That worked, didn’t it? They know how to deal with bad acid tripology. And the Dead have used Angel’s security corp. It works. Trust the tribe. Perhaps not the event’s wisest decision. Hyde Park had used UK Angels for security, but their San Jose and Frisco Angel counterparts are a… less placid breed. More venal Angels. A column of Harleys divide a Red Sea passage through the dark compressed audience mass…

Fact is, as the times darkened, the Stones were the only Rock band to reach higher through embracing its extremes. There are no hidden meanings in their albums that straddle the period. It’s not necessary to play those records backwards to decipher hidden satanic messages. They’re there in every aspect. The Stones feed on the darkness, the bad drugs, the heavy trips, the threatening vibe. Full-frontal details of Brian Jones’ drug-addled death are tautly recreated for Stephen Woolley’s ‘Stoned’ (2005), with Leo Gregory as Brian, and Peter Considine as builder Frank Thorogood, around who’s sordid 1993 deathbed confession it is supposedly based. And two days after his swimming-pool ‘accident’ – 5 July, filmmaker Leslie Woodhead was shooting ‘The Stones In The Park’ (1969), an electrically-charged free concert in Hyde Park addled with sixties signifiers – 3,000 stunned white butterflies uncaged, Paul McCartney in the audience, African tribesmen on-stage for “Sympathy For The Devil”, a Shelly oration – too frazzled, almost too fin de siécle to be totally on-message. ‘Each person an island within his own nostalgia’ writes ‘Oz’ editor Richard Neville after the Hyde Park free bash.

At Altamont, one year later, the dream is no longer soured, it’s over. Scaffold frameworks are hung with lights. Sound towers under a crescent moon. The sound system is barely sufficient, and crowd-management a disaster. Poor-quality hallucinogenics circulate. The dealer recites ‘hash-shees, LSD, psilocybin’ like a mantra, a poem. Bad trips. Bummer in the summer. There’s idiot-dancing that merges into acid-convulsions. For the Stones have always been about violence. Sneering aggression. Expectorating visceral chord-slashes. In reply to the Fabs “All You Need Is Love”, they retaliate with a sneering mocking cell-door slamming “We Love You” – no longer Blues as any purist would recognise it, but rooted in the incendiary upheavals of 1968, which fits them better… History has unsettled debts to pay. They’re all coming home today. If their role in 1969 is talismanic, here at Altamont is where history and myth autowreck with the now. Threatening my very life today. A disturbing microclimate groove-deep, a micro-nation in extremis. Two punters are killed by a hit-and-run, while sleeping, gut-crushed in their sleeping-bags. Another, unidentified, drowns in a drainage ditch. But the most high-profile death is Meredith Hunter, kicked and beaten to death with pool-cues… writer Pauline Kael – in ‘The New Yorker’, accuses the filmmakers and the Stones of complicity in his murder.

Of course, the sixties didn’t run from 1960 to 1970, decades never conform quite to their signature dates, they leak over into each other messily so that what we think of as the sixties really began with the Beatles – say, 1963, and end – say, with Altamont. It’s only three weeks after the Beatles final UK no.1 – “The Ballad Of John And Yoko”, and the Stones final UK no.1 “Honky Tonk Woman” tops the transatlantic charts for a month through July into August. As a group, the Beatles are into their last twilight. The future up for grabs. But now, at year’s end, tipping into the new decade, in the UK the Archies’ bubble-pop “Sugar Sugar” battles it out with Rolf Harris’ kitsch “Two Little Boys” for no.1…

‘JUST TWENTY-TWO AND I DON’T MIND DYING…’

(Bo Diddley “Who Do You Love”)

Jefferson Airplane. A long loose spacey jam around Fred Neil’s “The Other Side Of Life” dissolves into a frightening melee of movement, figures and screaming chaos. ‘Easy’ soothes a luminous laser-eyed Grace Slick over the mounting confusion, ‘it’s getting kinda weird up here.’ Dreamy-balladeer Marty Balin jumps off-stage to intervene in a fight that’s suddenly taking place in the audience directly beneath them. He gets knocked out by an Angel in a high-visibility scuffle. Space-cadet Paul Kantner vainly tries alerting the audience to what’s going down. ‘Hey man’ he announces from the stage, ‘I’d like to mention that the Hell’s Angels just smashed Marty Balin in the face and knocked him out for a bit. I’d like to thank you for that.’

A huge Hell’s Angel is on stage now, grabbing the mike from him, and starts into threatening him, ‘let ME tell YOU what’s happening!’ ‘I’m not talking to you man’ counters Kantner, outfacing the on-stage Angel, ‘I’m talking to the people who hit my lead singer in the head…’ while in the audience the Angels are fighting each other and the assembled hippies with sharpened broken-off pool cues. ‘That’s really STUPID, STOP IT!’ yells Grace over the mounting anarchy, ‘you’ve got to keep your bodies off each other, unless you intend love.’ Then she tries a slightly more conciliatory ‘people get weird, and you need people like the Angels to keep people in line. But – the Angels also, y’know – you don’t bust people in the head for nothing. So both sides are fucking up temporarily. LET’S NOT KEEP FUCKING UP…!’

Another fight barely avoided. It’s scary scary footage with the fear burning off each frame, as Angels bludgeon the Hippie dream to death with pool cues and chains. ‘There you go’ Grace tells me brightly, some years later. ‘The ‘Monterey Pop’ Festival was the bright beautiful event. And the dark side of that is Altamont. With Jagger fully dressed as the devil (…an explosion of hacking laughter…), he had a devil outfit on that day (not on my DVD he doesn’t!). That was perfect, perfectly apt.’ But it remains chilling watching Grace trying to deal with the violence at that concert. ‘Yeah. But the truth is, I couldn’t see. I didn’t have my contacts on. Maybe I’d lost them. So, it wasn’t a matter of DEALING with it. I had to go over and ask the drummer what the hell was going on! So I didn’t really know what was happening. But I didn’t actually SEE a lot of that day up close – fortunately. It doesn’t sound like it would have been very interesting to watch anyway.’

Meanwhile, Jagger steps out of a copter into nightmare tension and tactile unrest, and immediately he’s punched by some low-life spaced high on something toxic. Omens are bad. Already doomed from first blueprint. No happy ending to this jaunt, that’s for sure. Tumult hangs buzzing, crackling like radioactive fall-out. A thumping in my head like it has to be… a heatwave howling through my veins, a hurricane whirling in my head, my cool disposition hanging by a thread. Eat the heat. Yeh, but it’s some kind of generational baptism to actually get to witness the spectacle that is the Rolling Stones in their natural stage-habitat, and that you’re able to tease out all those awkward inconsistencies. Of course, this entire ‘underground’ phase is riddled with contradictions that only become apparent with hindsight. Not so obvious at the time, although I guess there was always an awareness – and indeed, a celebration, of the essential absurdity of it all even then. Especially in its treatment of women. Although the whole shambling inchoate movement was able to recognise and fine-tune from its mistakes in a kind of crude evolutionary sense, and the counterculture press would subsequently become the first place to give space to Gay and Feminist issues ignored or ridiculed by the mainstream media.

But yes, of course, there are other offenders. It must be strangely unsettling for many survivors of excess when figures like Gary Glitter and Jonathan King are brought down so publicly, when surely they’re only token examples of what was going down at the time…? In innocence, or in altered states of morality, or whatever. How come the Stones were never brought to task for “Stray Cat Blues” – ‘I don’t care if you’re just fifteen-years old, I don’t want your ID’, not to mention old Chuckleberry’s ‘Marie’ who’s ‘only six-years-old’, or Donovan on his ‘In Concert’ (August 1968) album free-improvising ‘I’m just mad about fourteen-year-old girls’…? I was on the cusp of asking him about that one during an interview, but either lacked the courage, or time-restrictions got the better of me. And anyway, I kind of know the answer. They were different times. Different rules applied, or seemed to apply. Opening up sexuality is a good thing… isn’t it? Isn’t that what the ‘Skoolkids Oz’ was all about…? The odd thing about retrospective morality is that it distorts all manner of things out of shape. Reading H Rider Haggard provokes all manner of similar responses over descriptions of black Africans. He’s always respectful and treats them as a proud and courageous people, but even that’s a kind of subtle marginalisation, in that he’s applying separate standards to them than he applies to devious and corrupt Europeans, they assume the ‘noble savage’ attributes. Being smart after the event is a wonderful thing.

At least, back then (with the u/g press), things were attempting to evolve and work out some kind of meaningful behavioural ethic. I remember Roger Hutchinson (of ‘It’) pacing up and down running through the ethical equation of whether to accept questionable ads for imported erotica for the classified columns, does that stuff represent liberation of exploitation? Capitalist acquisition, or fun sexuality? Is there some fine line in there that decides? And – in a hard financial sense, can we afford to turn away advertising revenue that can mean make-or-break for the magazine, enabling it to go on and publish more worthwhile stuff? Does the one vindicate the other? Or do they cancel each other out?

Meanwhile, over their five-decade (and counting) history, every twist, turn and litigation of every Stones’ incarnation has been captured, staked-out and dissected on celluloid. The ‘Out Of Our Heads’ (1965) pissing-up-against-the-wall era-kids had the antics of ‘Charlie Is My Darling’ – Peter Whitehead’s seldom-seen ‘True Life’ proto-Spinal Tap, instantly-withdrawn intimate celluloid-portrait shot in rain-drab 1965 Ireland. A drunk Jagger doing karaoke Elvis. Brian getting ‘surrealism’ seriously mis-defined. And candour from Bill Wyman owning up ‘I’m not a musician, I just play in a band, you know.’

Then the 1968 radicals could ponder Jean-Luc Godard’s cinema vérité ‘Sympathy For The Devil’ (November 1968), enduring the tedium of the song’s painful evolution, spliced together with counter-cultural mutterings referencing the Black Panthers, LeRoi Jones and Eldridge Cleaver. They’d have to wait twenty-eight full years for Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s film ‘The Rolling Stones Rock & Roll Circus’ (1996) to reach the stores, allegedly withheld due to Jagger’s fears that the Who’s support-spot upstages them. And as for Robert Frank’s fantastic – suppressed, bootlegged, and still largely unseen, film ‘Cocksucker Blues’ (1972)…? Those who’ve seen it will know it graphically screens the debauchery of the ‘Exile On Main Street’ tour. A young groupie fixing Keith with a heroin shot. TV’s thrown from hotel windows. And after Keith passes out, Jagger’s flair for micro-management still kicking as he networks to Atlantic Record’s Ahmet Ertegun. But there’s a tellingly intimate moment where Mick & Keith are sitting post-gig in a hotel room, playing records and talking music. Though there are others in the room, they’re oblivious to everything else, telepathically attuned to each other to the exclusion of everyone else. A later scene, in another hotel suite, eavesdropping Mick with new wife Bianca, provides sharp contrast. They barely speak. Mick hand-winds and plays a music-box over and over. It’s glacial how poorly they get on. The secret to the Stones longevity is there, in those two contrasting clips. The trickily fragile yet amazingly strong Jagger-Richards bond.

Rockumentary-maker Albert Maysles had started out as a psychology teacher shooting a docu-film about Russian mental hospitals. By the time he made ‘Gimmie Shelter’, he was already known for his ‘What’s Happening! The Beatles In The USA’ (1964). Then, in cahoots with film-makers David Maysles and Charlotte Zwein, Albert travelled cross-continent embedded with the Stones’ entourage to perfectly capture the exhilarating highs of the Madison Square Gardens performances, to the dysfunctional bedlam that unfolds at Altamont. ‘The Rolling Stones. Uncut. Uncensored. Unsurpassed’, it says on the original video-box, ‘the most disturbing, powerful and insightful moments ever to be recorded on film of the young generation raised on Rock’ (quoting ‘Newsweek’). But these events provide the framework. It’s the films within the film that freeze this into landmark docu-drama. The unguarded backstage bits. The yawning ennui as the group listen to a pristine-sharp “Wild Horses” playback tape. Jagger piss-taking himself, mock-aping his own prissy stage-dance across the hotel floor. This is a film as infamous for the paradoxes it randomly throws up as for whatever trace of musical genius it gleans. This is as close as you get without actually being there.

Later, lost children of the eighties were treated to the gaudy bloated spectacle of Hal Ashby’s ‘Let’s Spend The Night Together’ (1983) documenting the ‘Tattoo You’ tour. And it comes as no surprise that Martin Scorsese was minded to add his own entry to the filmic register with ‘Shine A Light’ (2008), shot at a single New York venue, with the Stones playing the relatively intimate Beacon Theatre. Scorsese’s preoccupation with the Stones in general… and with one defining number in particular, is a matter of (probably vinyl) record, thirty-five years earlier he’d used their music in ‘Mean Streets’ (October 1973). Not that he’s alone. It’s decades since “Gimme Shelter” was recorded for ‘Let It Bleed’. A song that’s attracted more mythological baggage than most. Supposedly Keith – in a jealous jag after watching Anita Pallenberg nude-cavorting with Jagger on the ‘Performance’ set, wrought the toxic opening in his car. Merry Clayton sang it until her voice cracked, so ripped it brought on a miscarriage as she left the studio. The lyrical dread and sense of impending doom (‘…rape, murder, it’s just a shot away’) gets fed into Scorsese’s movie. Using the track as shorthand for personal apocalypse. Now – as Philip French acutely observes, the Stones hire ‘top directors to do their bidding the way renaissance princes and popes engaged the old masters to paint portraits’ (‘Observer’ 13 April 2008).

Don McLean refers to Altamont chillingly in his extended “American Pie” – ‘as I watched him on the stage, my hands were clenched in fists of rage, no angel born in hell, could break that Satan’s spell… I saw Satan laughing with delight, the day the music died…’ And Stanley Booth details it in his book ‘True Adventures Of The Rolling Stones’ (Canongate, 1984, reissued 2012), a candid access-all-areas record of the tour, documenting both its carnivalesque excess and its mundane grind. The book’s publication was delayed due to Booth’s clinical depression and his LSD-habit, but its candour wouldn’t even have been possible now he admits, now Rock has become a corporate enterprise in which ‘everybody has their own representatives and lawyers and dressing rooms.’

Stanley Booth was at Altamont, I wasn’t. Instead, I see the Rolling Stones for a third time when they play Roundhay Park. A chance to take its pulse, and check for life-signs. The sun pours down like buttermilk. It’s already getting claustrophobic in the privileged confines of the royal Press Enclosure, so it’s walkabout time, comparisons storming. Thinking Bob Dylan’s Blackbushe Aerodrome Hippies Graveyard (July 1978) – surely an analogous cultural manifestation? that was all brown rice ‘n’ herb, all street theatre groups, psychedelic buses ‘n’ tepee’s, each stall unfurling its phantasmagoric ware of rare precious and beautiful bootlegs, CND and alternative-art texts, hand-carved jewellery and exotic drugs.

Here, it’s all red-blood materialism – we got kebabs, curries, real meat hamburgers, pancakes, German sausages, Mexican chilli, pizzas, fruit, filled potatoes and soft drinks. And we got strictly licensed merchandising. Stones posters and flags, Stones programmes and sweat-shirts, Stones badges and patches. Altamont it ain’t. Today no-one gets stabbed, the worst thing that happens is you get overcharged for a rather cruddy T-shirt. And over it all that endlessly boring digitally recorded L.A. support-spot soft-rock blands on – is this REALLY the company they choose to keep? Less Street-Fighting Men with Devilish Sympathies, more West Coast Under-Assistant Promo-Man…

But more, Jagger is the grotesque comic jester, his actions so mannered they’re absurd, like he’s deliberately sabotaging himself through a more exaggerated garish caricature than even his most boorish TV parodist would dare, and he’s ridiculing the punters for buying it, and for gullibly taking in the whole outlandishly ludicrous premise on which it operates. Yet he’s also magnetic, mesmerising, trapping all eyes. It’s showbiz, it’s performance, but they don’t come more charismatic. Bill Wyman is stood immobile behind him in blue unzipped tracksuit. It’s easy for him to get eclipsed. And Charlie Watts stays near-invisible behind the gantry of amplification stacks. But it comes apparent that their combined primitive rhythmic strength is by no means slight. The Stones sound is unique, and a large part of it rests on the steady reliable organic interaction twixt bass and drums. If anything of the early Route 66 Chicago Blues (or even Croydon Blues) raunch remains it’s to be found there in their constantly thunderous gangling millstone grit. And it lays down the tight base for the essential looseness all around, making it possible, giving it shape and anchoring it to form. It allows the long improvisations to be spun out around Jagger’s callisthenics…

“IN SLEEPY ROUNDHAY PARK THERE’S JUST NO PLACE FOR

STREET-FIGHTING MEN…”: THE ROLLING STONES LIVE IN LEEDS

‘Peace, he is not dead, he doth not sleep,

he hath awaken’d from the dream of life,

Tis we, who lost in stormy visions, keep

with phantoms an unprofitable strife

and in mad trance, strike with our spirit’s knife

invulnerable nothings…’

– Percy Bysshe Shelley ‘Adonais: An Elegy On The Death Of John Keats’

Rock academics debate the sound-slur at the guitar-centre of “Jumping Jack Flash”, was it deliberately and precisely placed by applying a finger’s-pressure to the revolving spool at that exactly chosen moment? Or was an accidental tape-lag overlooked at the editing stage? – or a combination of both, a fortunate malfunction that sounds good, so stays in? They were always better than you imagined. While “Stupid Girl” and “Under My Thumb” aroused the justified ire of Feminists, the Stones were also perceptively delineating hypocritical class put-downs with the French sway of “Back-Street Girl”, a dialogue in which the narrator lays out the rules his mistress must abide by, or defining the geographical limits of class with ‘she gets her kicks in Stepney not in Knightsbridge any more’ (“Play With Fire”). A distinction I was incapable of appreciating at the time. But they, a clutch of years ahead of me, phrased its intricacies in lyrics that still impress. Sniping wise beyond their years with an analytical precision that Lennon & McCartney couldn’t touch, yet relegated to ‘B’-sides or overlooked album tracks.

Jerry Garcia is washed by sunset sun-glow. Hank Harrison reports a later exchange with him. ‘Hey, Garcia, did ya’ see the Altamont Movie?’ ‘I’ve only seen bits and pieces… The rest of the guys have seen it, and they didn’t dig it. I didn’t want to see it, really. It’s like doin’ a song about violence – amplifying and promoting those vibes. I think that anyone who’s puttin’ anything out into the media, into the mass consciousness, has got a responsibility to try and put out good things, positive trips rather than negative trips’ (‘The Dead Book’ Links, 1973). ‘The movie was a good movie, the photography and the editing… In spite of that, the people who’ll see the movie are not all going to have the ability to view that thing on an aesthetic level, or to absorb the impact. It’s puttin’ down one more paranoid possibility, one of the infinity of paranoid possibilities.’

‘I’ve worked out the essence of the way it was that day, and it was so weird, man’ Garcia expands, ‘I took some STP, and you just don’t know… Phil and I, we got off the helicopter and we came down through the crowds, and it was just like Dante’s Inferno… the River Styx. It was spreading out in concentric waves. It was weird… fuck, it was weird. It wasn’t just the Angels. There were weird kinds of psychic violence happening around the edges that didn’t have anything to do with physical, shit, I don’t know – spiritual panic or something. And then there were all those anonymous, border-line, violent street types, that aren’t necessarily heads – they may take dope, but that doesn’t mean they’re heads – and there was a lot of, you know, the top forty world… pop tarts, and anybody could have been a killer, or anybody, for that matter…’

For the Dead, there were also issues of personal responsibility, ‘Obviously, it was something very heavy for us to see what we had initiated by just, on a good day back in ’65, goin’ to the Panhandle and settin’ up and playin’ for free – we saw it turn into that. I mean, it wasn’t lost on us, man. Altamont was the price that everybody paid for having that little bit of sadism to colour their sexual scene. The Rolling Stones put out that little bit of leather. Obviously, there’s a lot more to it than that, but I prefer this view. It’s because the environment I live in is a high-energy one, and everyone is really conscious of this shift – we’ve all had that experience, of saying the wrong thing (or the right thing, as the case may be) and all of a sudden… bam, it’s a whole different situation…’

This night, everything seems to regress to barbarism. The Stones make them wait. To build expectation. Part of the regular tour-theatre. Even the lights in the med-tents are cut so the only illumination is a single spot picking out Jagger’s entrance. And ‘Oh yeah’, a smiling Jagger begs to introduce himself. They do “Jumpin Jack Flash”, “Carol”, “Under My Thumb”, “Sympathy For The Devil”, “Slow Blues”, “Midnight Rambler”, “Honky Tonk Woman” and “Street Fightin’ Man”. Although it’s edited down for the film, the tour is well-documented. There’s the rough-cut vinyl bootleg ‘Liver Than You’ll Ever Be’. The official album ‘Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out’ (September 1970, extended Anniversary edition, November 2009). And every tour-step written-up by fledgling ‘Rolling Stone’ magazine, when it was less the mainstreamer it is now, more a ragged community flier, a counter-culture print-radio. From the first, the night is doomed. ‘Something very funny happens when we start that number’ gags Jagger as “Sympathy For The Devil” grinds to a messy halt. He’s touching-close to the audience front-line. A dog lopes past between them, unconcerned. The Stones play with fire. Gantry-lights radiate like lost suns caught on scaffolds. A topless girl half-scrambles onto the stage, only to be shoved back. Flabby bare burger-arses wobble and quiver. Blood and abrasions, already.

News Agencies later report a ‘drug induced riot’. How do the Stones react? How does Lucifer react? Hellfire vociferation? No. Rather, he’s helpless facing such brutality, from the first moment it disrupts their set. Jagger twitches, hands on head, ruffles down his front, long draping sleeves. His balletic footwork falters, and Satan stops singing. He stops. He tries to cool things – ‘Why are we fighting? C’mon!’ Then more forcefully, ‘that guy there, if he doesn’t stop it, man… Listen, either those cats cool it man, or we don’t play!’ A coyote-headed Angel joins him at the mike in a solidarity-gesture. ‘Don’t let’s fuck it up man.’ Too late, it’s already fucked. Then BAM, Meredith Hunter, the black eighteen-year-old who draws a long-barrelled revolver, is stabbed and kicked to death by Bikers while the Stones are on stage. Jagger finally calls for an ambulance, and the victim is helicoptered out. Even though they don’t yet realise the full extent of it, it’s now a whole different situation. A black man, brutally offed at the epicentre of a white crowd by white thugs, as white men play their take on black music. Bill Wyman stands impassive. Mick Taylor impales a cigarette-butt on the tuning-pegs of his guitar-neck. They try “Under My Thumb”, a brain-eating solo, then they have to continue – on acceleration, to prevent a riot. They try “Street Fighting Man”, before escaping by their own ‘copter. Searchbeams strobe the survivors like a POW-camp break-out, the lights break into spectral rainbows.

The freak-flags still fly as “Gimmie Shelter” soundtracks the morning rabble in blankets, carrying mandalas, straggling past pylons by the gridlocked freeway, mangled pieces crawling home through an impressionistic haze. Long pennants curl and uncoil. Figures black where grit-slopes climb to the horizon. This is the end, beautiful friend. The end of the innocence. Perhaps it’s the time of season, perhaps it’s the time of man, astrologically-speaking, voodoo-wise. Brian Jones died 3 July. Marianne Faithful attempts suicide five days later. Now this. Smashing the illusion that all of the fragmented parts of the sub-culture could peacefully co-exist.

San Francisco Radio KSAN reports the event, asking ‘we want to know what you saw…?’

For Garcia, ‘Altamont was a valuable experience, for everyone who was able to learn from it.’ That means a lot…

‘AFTERMATH…’

In 1969 to be young and white and male was to be the Crown of Creation. That’s not to be ageist, racist or sexist. It’s just, how it was. By the twentieth-century’s end, that was no longer true. Girls were smarter. Blacks were well-cooler. White kids mostly irrelevant. But back then, in 1969, it’s as good as it gets. Ever. By contrast, it’s easy to pity the generation who now have Susan Boyle’s “Wild Horses”. Or even George Michael who turns his cottaging notoriety into a hit video. Didn’t the “We Love You” slamming cell-doors, jailor’s boot-stomps and reconstruction of the Oscar Wilde trial do that already? The Stones have been in the game since the dawn of time, if not before. Their eyes have seen it all, glittering success, sad failure, critical acclaim, the best critical eulogies in Rock, and some of the worst. But always there, a presence. And inexorably, Meredith Hunter has become as much a part of their story as Mia Farrow is to Charles Manson.

Rock academics debate the exact point it all went wrong for the Stones. Their appearance on the ‘Ed Sullivan Show’ (15 January 1967), when they politely agree to neuter the lyrics of “Let’s Spend The Night Together” to ‘let’s spend some time together’. Is that where it started going wrong? Probably no, it was later. Was it when they settle for Ronnie Wood’s low-ambition equation ‘It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll, But I Like It’. The Devil is in the details, for even then they were already facing the underswell of a newer less sardonically mocking glam generation. Preparing to accept their less ambitious managed-decline role for the seventies. When Mick Taylor quits there’s a press-speculation feeding-frenzy over who’ll succeed him. Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Rory Gallagher…? Each name in the frame considered, and each could have seriously fractured the Stones back into some Blues-edged relevance. As it is they downhill slope into the easy Ronnie Wood option, the good guy, the mate who won’t distort things. Instead, if the future is up for grabs – after the decade’s last hurrah of ‘Exile On Main Street’, it was to be grabbed by Led Zeppelin.

No, the whole head-trip devoured itself at Altamont. There had been advance tremors with Brian Jones’ abrupt death, with the threatened jail-sentencing. But after Altamont fronted it all up, it could no longer be the teasing provocation it had been. In a blurred, shaky, slightly out-of-focus smudged screen-shot from ‘Gimme Shelter’, Jagger watches the playbacks in the editing suite, as they roll back and freeze on the precise moment of the killing. The girl in the crochet dress. The guy with the knife. And the long-barrelled gun. The way Jerry Garcia calls it, the ‘way it was put together was beautiful, even the stop-phase murder was ballet motion, a dance of death.’ And nothing would ever be quite the same again. Altamont took the Stones to the precipice. They could go no further. So they took a step back. Then another…

‘I ain’t not no peace-creep’ says Angel Sonny Barger on a radio phones-in, ‘I didn’t go there to police nothing, man.’ When the Angels hang you up, you know you’ve been hung. And later in the messy aftermath, Alan David Passaro, the Hell’s Angel who was tried and acquitted for the stabbing of Meredith Hunter, files an ‘invasion of privacy’ lawsuit on 16 February 1971 after the ‘Gimme Shelter’ film shows the stabbing…

BY ANDREW DARLINGTON

‘THE ROLLING STONES: GIMMIE SHELTER’

(1970, DVD 14 November 2000, then 11 August 2008 by Warner Home Video – WHV) Director, Albert Maysles, David Maysles & Charlotte Zwerin 2008 re-issue with full digital restoration of visuals and audio, plus 40-page booklet with snapshots and essays. Extras include: audio commentary by Albert Maysles, Charlotte Zwerin, and collaborator Stanley Goldstein: 1969 KSAN Radio Broadcast of Altamont wrap-up with excerpts from then-DJ Stefan Ponek: Backstage out-takes of the Stones at Madison Square Gardens: plus trailers. Factoid: one of the cameramen was a young George Lucas