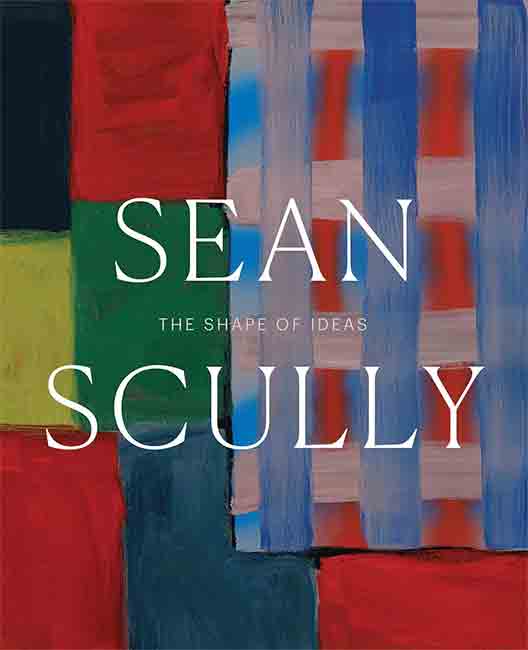

Sean Scully. The Shape of Ideas, Timothy Rub with Amanda Sroka (256pp, Philadelphia Museum of Art / Yale University Press)

Sean Scully. Human (315pp, Skira)

Sean Scully paints and sculpts and draws and prints with colour. His energetic and engaging painting has moved from complex hard-edged grids through vast multi-canvas blocks of stripes to energetic gesture, all the time accompanied by photography, watercolours, sketches, drawings, prints and sculptures.

His stripes were often associated by critics and viewers with cities, particularly New York’s gridded blocks, but his landscape photos – featuring the horizon line and layers of land &/or sea – and interviews often suggested otherwise. Over the years Scully’s persona has changed too, moving from aggressive and outspoken to a more ‘spiritual’ and gentler person, engaged with his audience and the world around him. Being a parent again, later on in life appears to also have re-energised him and his work too; he is now outspoken about emotion and the human content of his at practice.

Sean Scully. The Shape of Ideas is a well overdue overview of his work, the result of a major retrospective in the USA, a surprising 25 years since the last. It’s a beautifully illustrated volume, with a number of astute essays about Scully and his work. Timothy Rub offers a lengthy and informed biography that focusses on the work in relation to Scully’s life, whilst Kelly Grover’s ‘The Soul of Feeling’, which follows, argues that Scully changed 20th Century painting by reintroducing ‘soul’ and feeling back into abstract paintings as it headed off into minimalism and conceptualism. Both are fully illustrated, not only with the Scully work under discussion but also work by those who have influenced and inspired him.

After this there are 120 pages of glorious colour reproductions, which move from a 1972 woven canvas to some of Scully’s current Landline and Untitled (Window) series. En route there are key works along with examples of all his outputs, including many that will be new to many. The book ends with a selection of previous key critical texts which explore Scully’s work from a number of critical standpoints and different focal points. I confess I have most of these, but many will not and it is good to have the relevant writings by the likes of William Feaver, Sam Hunter and Donald Kuspit gathered together.

Scully’s recent ‘soul’-ful paintings have seen him directly engaged with spiritual sites. He has designed and had built a new chapel for an abbey near Montserrat in Spain; this includes many works specifically made for the chapel, including altar furniture and frescos painted directly onto the wall in the Renaissance manner. He has also engaged with religious buildings as exhibition spaces, and Human is a catalogue of his exhibition at the Basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice.

The exhibition not only carefully selected and placed previous paintings against the white walls of the church’s various spaces, but included many works specifically made for the venue. Most striking is ‘Opulent Ascension’, a tower of colour installed in the main church. Constructed of square wooden blocks covered in coloured felt, the simplistic sculpture somehow fills, engages with and changes the sacred architectural space. The catalogue essays reference ideas such as the Bible story of Jacob’s Ladder but I think the piece’s title says all you need to know.

‘Brown Tower’, a smaller steel version of the same idea, and a wooden tower built from railway sleepers, were placed outside in the basilica grounds, whilst drawings and watercolours for and from the sculptures and paintings on show were exhibited in glass cases. In addition a stunning hand-painted book was placed on the lectern in the Choir. Here, amongst drawings and watercolours, Scully documented some of his ideas, his aspirations for and personal associations with the work he had chosen to exhibit here. Obviously, there are clear references to and influences from illuminated manuscripts and books of the past, but Scully’s work is clean and simple, allowing air and light into his work to document his thought processes and artistic desire.

If I am less convinced by the figuration Scully has occasionally chosen to work with recently, that is far out-shadowed by the body of work Scully has produced over his lifetime. His energy and engagement with ideas, colour, paint, light and people is absolutely astonishing. He truly has explored what it is to be human, offering his findings to anyone who will pay attention on the way. His colourful reports are consistently wondrous and inspiring, and these books come close to capturing that.

Rupert Loydell