By Leon Horton

Since time immemorial man has used other species to fight his battles. From Hannibal and his elephants crossing the Alps to ambush the Romans during the Second Punic War, to the doomed horse-mounted Light Brigade charging entrenched Russian artillery in the Crimean, animals have long been unwitting conscripts in our ever more determined efforts to wipe each other from the planet. In this technological age of remote-piloted drones and wire-guided missiles, we might be forgiven for thinking that animals have finally earned an honourable discharge from the horrors of the battlefield. The truth, sadly, is a horse of a different colour…

We all know of the role horses have played throughout the history of warfare (there must be a statue in almost every city across the globe to commemorate the fact), but who among us knows about the use of bat bombs, nuclear chickens or terrorist-seeking gerbils? And if you think that sounds crazy, what about snake grenades, surveillance squirrels and remote-controlled sharks? If it wasn’t true, you’d have to make it up. But make it up is what the men in white lab coats continue to do, and what sounds like the stuff of fiction – of Hollywood at play – is more often military hardware.

It’s nothing new, of course. Much has been written about Hannibal and his use of elephants, but few people know of his serpentine naval tactics. In 190 BCE, while working as a mercenary for Prusias I of Bithynia (in modern day Turkey), Hannibal was engaged in a battle at sea against Eumenes II, king of Pergamum. Hopelessly outnumbered by the approaching Pergumese fleet, Hannibal had to think outside of the box.

Confident of impending victory, what Eumenes didn’t know was that Hannibal had ordered his men to collect as many poisonous snakes as they could find and load them into thousands of clay jars. When the enemy was close enough, the jars were hurled like grenades – smashing on the ships’ decks and releasing their venomous payload among Eumenes’ terrified sailors. The result: pandemonium. The outcome: glory for the Carthaginian underdog. Hannibal, it seems, had a knack for biological warfare.

The Dogs of War

History is littered with the military use of animals, both as beasts of burden and as weapons of war; but it is to the technological age that we must look to find the most bizarre, not to say ill-conceived, attempts to militarise other species for our own ill-gotten gains. Even man’s best friend, the faithful and ever loyal canine, could not escape the call to arms.

Dogs, like horses, have been drafted into the armed forces since they were first domesticated. History records that the ancient Greeks, Romans and Celts all used them, and their use was manifold: as scouts, couriers and sentry guards they were unsurpassed; as frontline warriors they were indispensible, proving their bravery time and again. But all that is as nothing, when you consider how the Russians ill-treated their four-legged friends.

During World War II, the Soviet Union attempted to use dogs to fight German tanks. Dogs with explosive packs strapped to their backs were trained, Pavlov-fashion, to seek food under tanks; where they were then detonated. In the battlefield, however, many of the dogs – who had been trained using stationary tanks in a fuel-saving measure – quite sensibly refused to engage moving machinery under heavy artillery fire and, terrified, ran back to their masters… with devastating consequences. The Soviets claimed the program had helped destroy over 300 tanks, but whose tanks remains a mystery.

Bombs in the Belfry

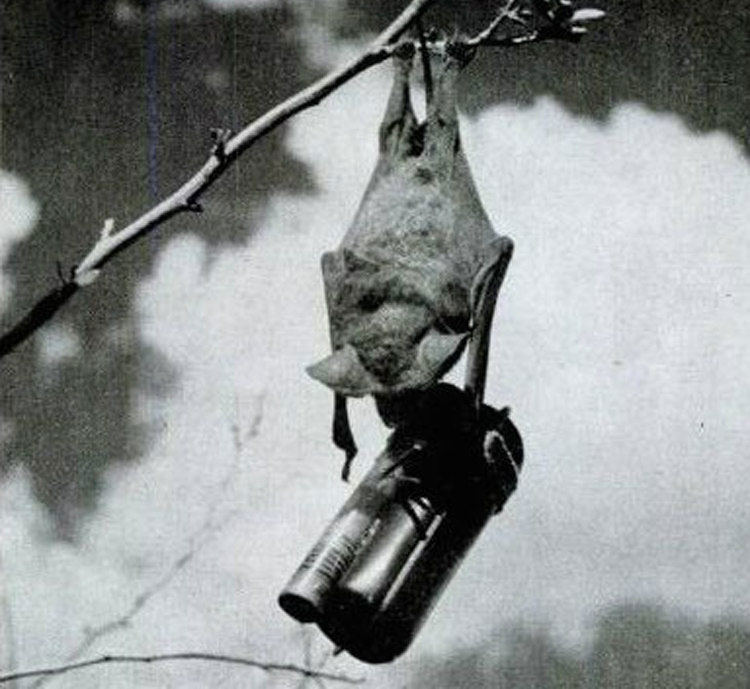

Not to be outdone by their Soviet allies – and with the atomic bomb still on the drawing board – the US government was coming up with its own far-fetched ideas. After their air force had been decimated at Pearl Harbour, the White House was desperate to find an effective way to attack Japanese cities – desperate enough to listen to dental surgeon Doctor Lytle S. Adams, who proposed that Mexican bats could be turned into small incendiary devices and dropped behind enemy lines from planes.

Adams suggested strapping small bombs to Mexican bats, which can carry three times their own body weight, loading them into cage-like shells and dropping them over designated targets. The bats, he theorised, could be released from the shells mid-drop and, following their instincts, would find their way into factories and other buildings where they would rest until the poor things exploded. Since Japanese buildings were built primarily from bamboo and paper, the resulting fires would be devastating.

The government took the idea seriously enough to invest an estimated $2 million, and despite an initial setback (the exploding critters set fire to the Air Force base at Carlsbad, New Mexico) the project looked set to go after they successfully destroyed a mock-up of a Japanese city. Ultimately, however, with the atomic clock ticking, the government turned their hopes and fears towards Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project.

Doctor Adams continued to lament the death of his pet project, insisting that his bat bombs would have caused just as much structural damage as the dropping of two atomic bombs, but with less cost to human life – a bold assertion, but little comfort to the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Rodent Roll Call

Rodents are extremely intelligent creatures, but not so clever as to dodge the draft. Since World War II, when the British Special Operations Executive filled dead rats with plastic explosives, in the hope that the enemy would shovel them into factory furnaces, causing them to explode, many species of rodents have received their call up papers.

Although the exploding rat idea was canned on the grounds that it was impractical, that didn’t stop MI5, the UK’s counter-intelligence service, proposing the use of live rodents when it came to airport security measures. During the 1970s, when the hijacking of planes was fast becoming a serious global concern, the organisation considered employing a team of trained gerbils to sniff out potential terrorists before they could board.

According to Sir Stephen Lander, MI5’s former director, the Israelis had already put the idea into practice at Tel Aviv airport. It must have looked bonkers, but the gerbils, with their keen sense of smell, were installed at security checks – where they could detect high levels of adrenaline in passengers and bring it to the attention of guards by pressing a lever.

The idea was never implemented in UK airports, and the Israelis abandoned the system after it was discovered that gerbils couldn’t discern between a sweaty would-be hijacker and someone who was just scared of flying; or, for that matter, terrified of rodents.

One of the most unlikely rodent tales to hit the headlines came about in 2007, when Sky News – take it or leave it – reported that Iranian police had arrested 14 squirrels on suspicion of spying.

Citing the Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNC), Sky claimed the squirrels were rounded up near the Iranian border and found to be kitted out with surveillance equipment, quoting the Iranian national police chief as saying “I have heard about it, but I do not have precise information.” A UK Foreign Office source dismissed the claim as “nuts”.

Nuclear Fried Chicken

The cold war brought with it a whole raft of further bizarre attempts to use animals for military and espionage purposes. During the 1950s, the British government, fearful that West Germany might one day be overrun by Warsaw Pact forces from the east, initiated the Blue Peacock Project.

The plan was simple: to bury nuclear bombs in the ground, at strategic points along the North German Plain, for possible detonation later should the Soviets ever invade. Just one problem: the primitive electronic devices used in nuclear devices at that time were considered to be unreliable in frozen ground, and so an alternative had to be found.

Some of the brightest minds in Britain were tasked with finding a way of insulating the bombs. Working around the clock, discarding one idea after another, scientists eventually came up with the solution: chickens. Yes, that’s right: chickens. Simply keep a chicken inside the bomb, they said, with enough food and water to last out the German winter, and it will generate enough bio-genetic body heat to keep the bomb functional.

The British never went through with the plan, not because it was plainly ridiculous, but only because they feared the diplomatic implications of nuclear fallout on allied territory. The story was thought to be an April Fool’s joke until it was declassified in 2004. A spokesperson for the UK National Archives was reported as saying: “It does seem like an April Fool, but it most certainly is not. The Civil Service does not do jokes.”

Kittens in the Kremlin

Anyone who has ever owned a cat will tell you they don’t take orders, but the CIA was clearly ignorant of that fact when, in 1961, they instigated Operation Acoustic Kitty. The idea to medically modify moggies, at an estimated cost of $15 million, came about when America’s secret service realized that cats see better in the dark than humans.

If there was a better way to spy on Russian embassies, the CIA were blind to it, and so contracted the services of Animal Behaviour Enterprises (ABE) and their facilities at the IQ Zoo in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Bob Bailey, general manager of ABE, had previously worked on the Navy’s Marine Mammal Program and seemed the logical choice to lead up the research. “We never found an animal we couldn’t train” he told the Smithsonian.

According to Bailey, the unfortunate cat was surgically implanted with a microphone in its cochlea (inner ear), which was connected to a battery and transmitter in its ribcage. “We found that we could condition the cat to listen to voices,” Bailey was quoted as saying. “We have no idea how we did it. But we found that the cat would more and more listen to people’s voices, and listen less to other things.”

The cat’s movements could be directed with ultrasonic sound, but it had a tendency to wander off when hungry – prompting further surgery. Finally, after five years of research and intensive training, the cat was deemed ready for its first field test and was driven to a Soviet compound on Wisconsin Avenue in Washington DC, where it was released from a parked van across the road.

No amount of research or development could have predicted what happened next. According to ex-CIA official Jeffrey T Richelson in his book The Wizards of Langley, the cat dutifully padded off on its first mission… and was run over by a taxi. The project was declared a feline failure and cancelled in 1967, but it only came to light when the relevant documents were declassified in 2001. Cats, they revealed, couldn’t catch a cold war.

Navy Seals

So far: no good. Many modern attempts to train animals as weapons or tools of war have failed miserably, on land and in the air. In the water, however, there have been several success stories; if you can call them that. Dating back to the 1960s, the US Navy’s Marine Mammal Program has been instrumental in training seals, sea lions, whales and dolphins for military service – most successfully with the Californian sea lion and the bottlenose dolphin.

Both species, with their superlative underwater vision and agility, can be trained to perform a variety of tasks: to spot enemy swimmers; to alert nearby crew to the intruders’ presence; and, in the dolphins’ case, to detect and retrieve underwater mines. Sea lions can even attach a clamp to a swimmer’s leg, restraining the enemy from going any further, before deploying a floating buoy. These animals’ ability to dive to great depths also enables them to help with tagging and recovering objects from the seabed.

Arguably, the most disturbing use of dolphins came about during the Vietnam War under the United States’ Swimmer Nullification Program. Initially, dolphins were trained to seek out Vietcong divers, tear off their facemasks and air tubes, and drag them back to the navy for interrogation. They were so successful at this that the order was given to arm the dolphins by attaching knives to their snouts. They could then swim headlong at the enemy and drive the knives into them, killing them at source.

If that wasn’t murderous enough for the Marines, what happened next was truly sadistic. This time hypodermic syringes filled with pressurised carbon dioxide were fastened to the dolphins’ snouts. Any diver injected with this would ‘blow up’ like a balloon and burst. In all, 40 Vietcong were said to have died in this manner, but the Marines’ sympathies lay more with the two US divers who suffered the same fate by mistake.

In 1976 a partially declassified CIA document revealed that the Soviet Union was also conducting research into dolphins: training them to carry explosives towards enemy warships where they could be remote detonated – turning them into suicide bombers. The program was officially abandoned due to lack of funds, but marine mammals continue to be used for military purposes to this day. In 2003, sea lions and dolphins were sent to the Persian Gulf to protect U.S. and British warships during the Iraq War.

Jaws 2, Enemy nil

As if there wasn’t enough death in the water, in March 2006 New Scientist reported on a bizarre project funded by the US Defense Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to create remote-controlled sharks. In a move reminiscent of a Bond villain, scientists at Boston University, led by biologist Jelle Atema, implanted neural electrodes into the brains of dogfish sharks. The implants stimulated the sharks’ sense of smell with an electrical current, fooling the poor animal into believing a source of food was nearby. This, in effect, allowed the scientists to steer the sharks where they wanted.

The experiment – one of a number around the world to receive ethical approval to develop implants that can manipulate animal behaviour – was developed to improve our understanding of how animals interact with their environment, and to help further research into human paralysis. Controversially, however, the Pentagon was already looking further out to sea at the military potential of this scientific breakthrough, with DARPA at the helm. According to New Scientist, DARPA, armed with a $600,000 grant, was “aiming to exploit sharks’ natural ability to glide quietly through the water, sense delicate electrical gradients and follow chemical trails.”

It won’t be all plain sailing, mind you, as the magazine reported: “As wild predators, it is very easy to exhaust them, and this will place strict limits on how long the researchers can control their movements in any one session without harming them. Despite this limitation, though, remote-controlled sharks do have advantages that robotic underwater surveillance vehicles just cannot match: they are silent, and they power themselves”.

It remains debatable what the Pentagon has in mind for remote-controlled sharks, but a bomb with a nasty bite is a safe bet.

Soldiering on…

It has been difficult to write this article without a sense of irreverence, since much of the subject is so outlandish it belongs in a Hollywood movie. But events such as the exposé of weapons testing on animals at Portland Down (see sidebar) are not fiction; are, in fact, a savage indictment against our ability to find new ways of killing each other, and our willingness to use other species in order to do so. In an age where technology affords us the ability to wage war without committing soldiers to the field, it seems doubly perverse that we continue to press-gang animals into doing our dirty work.

About the Author

Leon Horton is a cultural journalist and humorist. After gaining his masters degree from the University of Salford, he cut his teeth on local magazines, enjoyed a caretaker stint as the editor of Old Trafford News then returned to freelance writing. His writing is published by International Times, Nexus New Times, the Animals’ Voice, Empty Mirror and Erotic Review.

Leon lives in Manchester, England, and can be contacted at [email protected]