This article is respectfully dedicated to my friend Paul Clements (1964-2017), another good Doctor sorely missed.

Owl Farm, Colorado, February 20, 2005 – 5:42 p.m. Hunter S. Thompson, hell-raiser and author of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, takes a phone call from his wife Anita at the Aspen Club and apologises for almost accidently shooting her the previous day. He asks her to come home, sets the receiver to one side and puts a .45 calibre pistol to his head…

In the next room, daughter-in-law Jennifer and grandson Willy hear a shot ring out, but this being the home of Hunter, where guns are as commonplace as cutlery, they ignore it.

Moments later, Hunter’s son Juan finds the body, calls the sheriff’s department then goes outside with a shotgun and fires three blasts into the air to mark the passing of his father.

Age sixty-seven, the prolific Gonzo journalist and “wild man of American writing” has filed his last story.

Never hesitate to use force. It settles issues, influences people. Most people are not accustomed to solving situations by immediate and seemingly random applications of force. And the very fact that you are willing to do it – or might be – is a very powerful reasoning tool. Most people are not prepared to do that. You can establish the right reputation in this regard – you might, right in the middle of a conversation, just swat some motherfucker across the room. Make his blood shoot out in big spurts.

(Ancient Gonzo Wisdom)

Hunter S. Thompson was an enigma. A riddle wrapped in a mystery waving a loaded gun in your face. It is almost impossible to say anything about Thompson that hasn’t been said before, mostly by the good Doctor himself. It is equally difficult to know where the reality ends and the mythology begins. But that’s what Thompson was all about – muddying the waters of factual reporting, placing himself at the centre of the story, and sacrificing any notion of journalistic objectivity to the absolute conviction he was a serious writer of fiction, in the same vein as Ernest Hemingway or F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Thompson had many lives. He was the fearless young journalist, beating his way through the countercultural hippy scene in San Francisco, who in 1967 spent a year riding with the Hell’s Angels, took a nasty beating himself and survived to tell the tale in his first book.

He was “Raoul Duke”, who staggered out of the crashing wave of 1960s optimism in 1971, armed with an arsenal of drugs, giving us Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and Gonzo journalism.

Perhaps most importantly of all, he was the leftfield political commentator who got to share a car with President Nixon and talk about football (“The only time I ever saw the bastard tell the truth.”); run for office himself as Sheriff of Aspen, Colorado (“I proved what I set out to prove. That the American Dream really is fucked.”); and was the first to see through would-be-president Clinton’s primary colours (“The morals of a lizard.”)

By turns exhilarated and disgusted by politics, in 2000 Thompson returned to his first love: writing about sports, contributing a weekly column (“Hey Rube”) to the ESPN website. But thanks to a braying crowd of fans, many of whom had only read Fear and Loathing, or watched the 1998 Johnny Depp movie of the same name, he was rarely allowed to escape his past, or the monstrous creations of his often regretted self-mythologizing.

I’m too old to adopt conceits or airs. I have nothing left to prove. It’s kind of fun to look at it – instead of a personal challenge to the enemy out there, just enjoy the evidence. I can finally look at it objectively. Not ‘Who is this freak over here?’ but ‘Who am I?’ I’ve gotten to that point where it’s take it or leave it. Whatever way I’ve developed seems okay to me on the evidence. So what if the score is against me? I’ve been on the battlefield for a long time. I suppose I always will be – just my nature.

(Ancient Gonzo Wisdom)

Thompson’s defiant act of suicide did little to persuade fans and critics alike that he was much more than the drug-fuelled outlaw journalist portrayed in the media. He was a difficult man, most certainly, demanding but fiercely loyal, with a deep-seated abandonment complex that tested the best of his friendships. To love him was to engage in combat with him. And to get to that version of the man, we need to look back into his childhood, past the high-rolling of Hells Angels or Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

Hunter Stockton Thompson was born on July 18, 1937 in Louisville, Kentucky, a city built on its chief exports of tobacco and liquor. Steeped in southern traditions and sporting many athletic clubs and literary societies, for some Louisville represented that most arresting of ideals: the American Dream and conspicuous wealth. On the other side of the street, however, it was a deadbeat town of drinking, gambling and crime.

Little wonder that Louisville would produce a prodigal son like Thompson. It would become his playground, his Alma Mater, his vision of the world in minutiae, but some must have thought it was God’s own work when six months before Thompson was born this city founded on vice met with almost biblical retribution when the banks of the Ohio River burst and plunged 70 percent of Louisville underwater. To those who came to know Hunter during his chequered childhood, it might well have seemed a portent.

In his comprehensive 2008 biography, Outlaw Journalist: the Life & Times of Hunter S. Thompson, William McKeen, professor of journalism at the University of Florida, wrote of his long-time friend and colleague: “Hunter was a difficult child. He was also charming, extraordinarily handsome, and self-assured.” Interviewed in 2004 on the Biography Channel for Biography: Hunter S Thompson, Sandra Conklin, Hunter’s first wife, said of her former husband: “Hunter came out of the womb different and somewhat angry. From talking to his mother, he was always different. He always had that charisma.”

Virginia Thompson, nee Ray, was twenty-eight when Hunter was born. The daughter of a Louisville businessman, she came from a relatively comfortable background (the family manufactured carriages before her father moved into insurance) and enjoyed the usual trappings of Louisville society. She was intelligent, and her father did well enough to send her to university. With the advent of the Great Depression, however, the family could no longer afford to support her through graduation, and by the time she met Jack Thompson in 1934, any dreams of a genteel southern lifestyle had all but evaporated.

Jack Thompson had been chasing the American Dream most of his adult life – never quite making it, never quite not – but he was no Willy Loman. All he wanted for his family was a nice home in a good neighbourhood, something he achieved in 1943 when he was able to put a down payment on a two-storey bungalow in Louisville’s first suburb, the Highlands. He was fifteen years older than Virginia, more worldly, and like her father, worked in insurance – which might account for her attraction to him. He arrived in Louisville after the death of his first wife, having left his first-born with relatives.

Being older, and no stranger to parenthood, Jack often took a back seat where his second son was concerned, but Virginia doted on Hunter. She was more lenient than most mothers, and from an early age it was Hunter not Jack who entertained visitors. “Even as a child, he worked a room,” McKeen observed in Outlaw Journalist. “When Hunter was around, the chemistry changed; you felt his presence before you saw him. In that seen-and-not-heard generation, Hunter struck even grown-ups mute with his powerful personality.”

With the arrival of baby brother Davison in 1939, the Thompson’s might have looked like the perfect all-American pre-nuclear family – if such a thing existed – but the times they were a-changing. The war in Europe was looming ever closer, and Jack Thompson took to drinking whiskey and listening to bad news on the radio; looking on from his chair on the porch as younger, more athletic fathers played sports with their children.

For the most part, the family would give Jack a wide berth when he listened to war bulletins and muttered darkly about the Japanese, but Hunter remembered those evenings with childlike reverence. “I soon became addicted to those moments,” he wrote in his memoir Kingdom of Fear. “There was a certain wildness to it, a queer adrenaline rush of guilt and mystery and vaguely secret joy that I still can’t explain, but even at the curious age of four I knew it was a special taste that I shared only with my father.”

Choosing the right friends is a life-or-death matter. But you really see it only in retrospect. I’ve always considered that possibly my highest talent – recognizing and keeping good friends. And you better pay attention to it, because any failure in that regard can be fatal. You need friends who come through. You should always be looking for good friends because they really dress up your life later on.

(Ancient Gonzo Wisdom)

The same year America entered the war after the bombing of Pearl Harbour, Hunter entered first grade at I. N. Bloom Elementary School, and quickly established his credentials. He was mischievous and funny, which failed to impress his teachers, but made him a focus of fun to his classmates. He had issues with authority, sure, but he was also a natural born leader, and he soon had his own gang of reprobates trailing behind him.

Cherubic wasn’t in it. Even at the age of five, Hunter had the ability to frighten and captivate children and adults alike. He would bark questions at his teachers – voice prematurely deep, sounding angry when he wasn’t – and snarl menacingly at his classmates. When he was elected to head the school safety patrol, no doubt after a vigorous campaign, the principal protested, calling him “Little Hitler.” “I wasn’t sure what that meant,” Thompson recalled in Kingdom of Fear, “but I think it meant I had a natural sway over many students. And that I should probably be lobotomized for the good of society.”

Out of school, Hunter’s gang would emulate real-life events playing war games in the woods in Cherokee Park, often with real-life consequences and injuries, with Hunter as usual taking the lead. When parents saw their children come home with bloodied heads and covered in bruises, they began to see the Thompson kid as a dangerous influence and warned their sons to stay clear of him. “Hunter was a sweat to be around,” friend Neville Blakemore told William McKeen. “I got increasingly uneasy with being around him because I knew he would eventually think of something to do to me.”

Hunter was Coyote, the trickster deity of North American mythology. Coyote was a mischievous, cunning and destructive force at work within creation. Mysterious and monstrous were his antics, as was the pleasure he derived from causing troubles and upsets on a daily basis. When the creator god Wonomi yielded power to Coyote, it was not, he said, because Coyote was stronger, but because man had chosen to follow him and not their creator. Legend has it Coyote killed himself and roamed the world as a spirit.

As much as he sought out mischief and trouble, Hunter was a seeker of knowledge, and the gang’s joyrides across town on their bicycles often led to sojourns in the local library. “There’d be a lot of camaraderie and loud talk until we’d get to the steps of the library, gang member Gerald Tyrell told McKeen. “Then we’d get quiet, go in, and get a book, and sit down and read. We’d leave in about two hours and get noisy again. It wasn’t until much later that I realized it wasn’t the normal stuff for a gang of boys to do.”

My parents were decent people, and I was raised, like my friends, to believe that Police were our friends and protectors – the badge was a symbol of extremely high authority, perhaps the highest of all. Nobody ever asked why. It was one of those unnatural questions that are better left alone. If you had to ask that, you were sure as hell Guilty of something and probably should have been put behind bars a long time ago. It was a no-win situation.

(Kingdom of Fear)

It was on the cards. It was bound to happen. A boy like Hunter was always going to run into the Law sooner or later, but his parents must have been shocked when two FBI agents came to their door and accused their nine-year-old son of destroying a federal mailbox.

His friends, they said, had already confessed, and put Hunter squarely in the frame for a crime that came with a five-year prison term. Hunter was guilty, of course – he and his gang had contrived, using ropes, to pull the heavy metal mailbox into the path of an oncoming bus, with devastating results – but realising his friends would never rat him out, he held his nerve, and with remarkable assurance for a nine-year-old boy guilty-as-sin, he turned the tables on his accusers and asked: “Who? What witnesses?”

Jack Thompson reiterated his son’s question, and the federal agents eventually left without their man, but it was a pivotal moment in Hunter’s development: “I learned a powerful lesson. Never believe the first thing an FBI agent tells you about anything – especially not if he seems to believe you are guilty of a crime. Maybe he has no evidence. Maybe he’s bluffing. Maybe you are innocent. Maybe. The Law can be hazy on these things…. But it is definitely worth a roll.” The mailbox incident was a confidence-builder, he would say later in life, but confidence was never Hunter’s problem.

In the days before Ritalin, sport was the answer. Sport, experts said, was the best medicine for taming the restless energy of wayward children. Louisville was mad for baseball, despite not having their own Major League team; and like his father, Hunter was passionate about the nation’s favourite game. He played in a church-sponsored league, as did many of his friends, and was considered an extremely good batsman.

At Bloom Elementary, Hunter led the campaign to form an extra-curricular athletics club, the Hawks, organised competitions with other neighbourhood teams, and won the interest of Louisville’s prestigious Castlewood Athletics Club. If the wind had blown in a different direction, the name Hunter S. Thompson might be remembered very differently.

But it was not to be. The spirit of Coyote chewed on his own tail. As Hunter grew, a physical disability – one leg shorter than the other – left unbloomed any flowers of romance that he might one day make a professional sportsman. It was painful to watch his friends surpass him on the playing fields, but the anomaly gave him his distinctive loping walk – a walk that would serve him so memorably in a lifetime of noteworthy “here-I-am-make-of-it-what-you-will-couldn’t-give-a-shit” arrivals and departures.

To get by you had to find the one thing you can do better than anybody else… at least this was so in my case. I figured that out early. It was writing. It was the rock in my sock. Easier than algebra. It was always work, but it was worthwhile work. I was fascinated early on by seeing my by-line in print. It was a rush. Still is.

(Kingdom of Fear)

As the gang’s creative mischief continued unabated – taunting other kids with a BB gun down at the creek, pretending to bullwhip each other in public, feigning epileptic seizures as a prelude to shoplifting – so too did their forays into the literary world. When gang member Walter Kaegi acquired a mimeograph they began publishing their own neighbourhood newspaper, the Southern Star. Kaegi was editor, but Hunter wrote much of the copy. It was juvenile stuff (the lead story in the first issue was about a fight Hunter provoked with new neighbours), but their efforts caught the attention of Louisville’s Courier Journal. Hunter earned his first writing credit age eleven.

After his first taste of the publishing world Hunter was hungry for more. He set his sights on joining Louisville’s prestigious Athenaeum Literary Association – but there was a problem. Firstly, he was too young. You had to be thirteen to join the hallowed ranks of the Athenaeum. Secondly, he was at the wrong school. The Athenaeum had started at Male High, a feeder school for the Ivy League, whereas Hunter had started at the less distinguished Atherton High School. He needed a plan. He needed a way out.

And then something truly serendipitous happened. After criticising their performance, Hunter was beaten up by the school football team with such alarming ferocity that it was deemed prudent by his concerned parents and teachers that he should transfer to Male High forthwith. With a salutary lesson on the redeeming effects of violence, Hunter got where he wanted to be. As for the Athenaeum, he would just have to bide his time.

Male High meant new friends – many seeking friendship as an alternative to being the butt of Hunter’s pranks – and wider scope for rebellion. Jack and Virginia fretted over Hunter’s increasing waywardness, but after Virginia gave birth to their third son James in 1949, they had little time or energy to do much about it: Virginia was forty-one, Jack fifty-three, and the burden of another child on Jack’s salary was stressful enough. Besides which, a much darker cloud was looming on the family Thompson horizon.

When I think of him now I think of fast horses and cruel Japs and lying FBI agents. “There is no such thing as Paranoia,” he told me once. “Even your Worst fears will come true if you chase them long enough. Beware, son. There is Trouble lurking out there in the darkness, sure as hell. Wild beasts and cruel people, and some of them will pounce on your neck and try to tear your head off.”

(Kingdom of Fear)

When Jack Thompson was admitted to Louisville Veterans Hospital in 1952, he had been suffering for months. He was exhausted, his muscles ached, his vision was getting worse by the day, and he could barely eat. The doctors diagnosed a chronic condition that attacks the immune system: myasthenia gravis. Three months later he was dead.

“His dad was a nice and quiet man who kept him on the straight and narrow as best he could,” Hunter’s friend Duke Rice told unofficial biographer Paul Perry, author of Fear and Loathing: The Strange and Terrible Saga of Hunter S. Thompson. “When he died, there was no one to do that. His life got turned upside down from that point on.”

Jack’s death sent the entire Thompson family into freefall. Virginia, with three young boys to feed, was forced to take a job at the public library – leaving the day-to-day care of her children to their widowed grandmother Lucille. Although the boys loved their Grandma (Mee-mo), she was no substitute in a time of grief. Hunter, suffering complex emotions of loss and abandonment by his father, deeply resented the daily absence of his mother. To make matters worse, Virginia started drinking heavily after work.

“Your mother’s sick again,” Lucille would tell the boys, as she helped her daughter to bed, but fourteen-year-old Hunter knew better. If he resented Virginia going to work, he positively hated her drinking, and the two would often have screaming slanging-matches. “Hunter had a real short fuse with all this stuff,” his brother Jim, then four, told E. Jean Carroll in her much-loathed pseudo-Gonzo biography Hunter: The Strange and Savage Life of Hunter S. Thompson. “He was intolerant and mean.”

Feeling abandoned by both parents, Hunter’s antics and wild behaviour increased exponentially. At Male High, he found new partners in crime (chiefly Sam Stallings and Ralston Steenrod, both older), started dating girls, and learned how to get hold of alcohol. Underage drinking, partying all night, and stealing, gave the teenagers the idea they were somehow untouchable: emulating Marlon Brando’s gang in The Wild One (one of Hunter’s favourite films), they roamed the neighbourhood looking for trouble.

And they found it – time and again. Whether threatening terrified store owners to sell them liquor, trashing pool halls, or robbing the collection box from a local church, it was clear which of the gang had adopted the Brando role. After they vandalised a gas station, the police came to Male High and arrested Hunter alone, taking him away in handcuffs. “I learned about jails a lot earlier than most people,” Hunter told High Times in 1971. “I was in and out of jails continually… for buying booze under age or for throwing fifty-five gallon oil drums through filling station windows.” And so it went on.

Still, at least he had the Athenaeum Literary Association. The Athenaeum – whose grand history stretched back to 1824…The Athenaeum – whose fifty or so members came from the upper echelons of Louisville society… At least there, Hunter could show off his prodigious writing talent and keep his delinquent behaviour in check. At least there, the spirit of Coyote could rest awhile. At least, that was how it looked to the outside world.

In reality, the Athenaeum (ostensibly a melting pot of cultural interests and social status) was like the Hellfire Club of 18th century Britain, with all its initiation rites and secret ceremonies. Members, drawn from three years of Male High – sophomore, junior and senior – had to be voted in, and were expected to prove their mettle in underage drinking and partying. They would meet every Saturday night, suited and booted, and were required to produce something of literary merit to be critiqued by their peers.

“It was a rather extraordinary thing,” Hunter’s friend Porter Bibb told William McKeen, “for forty-five testosterone-packed teenagers to sit there for three hours or more every Saturday night, reading the poems, the short stories, and the essays that they had written.”

Hunter, of course, was a natural, and much of his writing made the final cut into the Athenaeum’s yearbook, the Spectator. Age seventeen, in an essay titled “Security”, he wrote:

Turn back the pages of history and see the men who have shaped the destiny of the world. Security was never theirs, but they lived rather than existed… It is from the bystanders (who are in the vast majority) that we receive the propaganda that life is not worth living, that life is drudgery, that the ambitions of youth must be laid aside for a life which is but a painful wait for death… These are the insignificant and forgotten men who preach conformity because it is all they know. These are the men who dream at night of what could have been, but who wake at dawn to take their places at the now-familiar rut and to merely exist through another day… So we shall let the reader answer this question for himself: Who is the happier man, he who has braved the storm of life and lived, or he who has stayed securely on shore and merely existed?

(Reprinted in The Proud Highway)

Despite, maybe because of, his association with the Athenaeum, Hunter’s contempt for the middle-class mores of polite society saw Coyote raise his game in evermore defiant acts of gratuity. He staged a mock kidnapping in front of the queue outside a cinema (revelling in the fact it made the papers), spent nights in jail for drink-driving, and infuriated his friends’ parents when he got their sons arrested for trying to buy alcohol.

The career of a juvenile delinquent is finite by definition, and time and the patience of law enforcers, not to mention that of the local populace, were running out for the neighbourhood terror that was Hunter S. Thompson. The final straw came one night in Cherokee Park, June 1955, when he, Steenrod and Stallings, driving around with nowhere to go, decided they needed cigarettes. With teenage logic, no doubt fuelled by alcohol, instead of driving to the nearest store, they pulled up alongside a parked car.

The boys approached the car, where two young couples were enjoying a passionate evening. Stallings asked them for cigarettes, but the startled lovers refused. What happened next has long been a matter of dispute, but according to Hunter, Stallings threatened them. “‘All right, Motherfucker! You give me some cigarettes or I’m going to grab you out of there!’” he recalled. “Then he reached into the car and said, ‘I’m going to jerk you out of here and beat the shit out of you and rape those girls back here.’”

The driver of the car, Joseph Monin, later stated that Stallings threatened him with a gun, giving some credence to Hunter’s version of events, but according to McKeen in Outlaw Journalist, it was Hunter not Stallings who threatened the rape. Whatever the truth, the terrified victims handed over cigarettes and money, totalling eight dollars, and the three robbers stole off into the night – but not before Monin got their licence plate.

Hunter sobbed in the dock, Steenrod and Stallings (both sons of attorneys) got off lightly with probation and a fifty-dollar fine respectively, Virginia Thompson pleaded for her son, Judge Joseph Jull’s gavel went down – and Hunter got sixty days in jail. Even one of the victims protested at this, but Jull was unmoved. “What do you want me to do? Give him a medal?” Because of his lack of connections, the alleged threat of rape and his previous petty offences, Hunter Stockton Thompson met the full force of the Law.

Prison gives an artist credentials; for everyone else it takes them away. Incarcerated in Jefferson County Jail, seventeen-year-old Hunter had time to reflect on where his life was going. He would be in prison when his friends graduated from high school, he would be voted out of the Athenaeum Literary Association, he would never go to college…

On the day he should have graduated from Male High, Hunter gazed out from his prison cell and wrote:

I could see the moon hung high in the sky

and the mocking grin on his face.

I know he was looking straight at me,

perched high in my lonely place.

His voice floated down through the crisp night air

and I thought I heard him say,

“It’s too bad my boy,

It’s an awful shame,

that you have to go this way.”

(“The Night-Watch”/The Proud Highway)

In the event, thanks to his 18th birthday, Hunter made bail and served only half of his sentence – but by the time he came out his world was a changed place. Most of his friends had deserted him, and with the ominous warning “We’ll be watching you” from Judge Jull ringing in his ears, under the steely-eyed gaze of his hated probation officer, Mr. Dotson, he took a driving job delivering parts for a local Chevrolet dealer.

Or, if you prefer William McKeen’s version of events, he took a job driving a truck for a furniture store.

Whichever one it was, it didn’t last. With his love for speed, Hunter behind the wheel was always a risky prospect – something bad was bound to happen. According to McKeen, he backed the truck through a showroom window. According to Hunter, in numerous interviews and in his memoirs, he tried to take the truck down a narrow back alley: “I took it down an alley – a downtown alley at about 60 miles an hour and just – I mean, one inch off, just opened up the side like a can opener,” he told CNBC in 2003.

The prospect of going back to jail was too much, and so, with barely any hesitation, Hunter simply walked across the street to an Air Force recruiting office and promptly enlisted. “I took the pilot training test and scored like 97 percent. I didn’t really mean to go in there, but I told them I wanted to drive jet planes, and they said I could with that test. So I said, ‘When can I … when can I leave?’ And the recruiting officer said, ‘Well. Normally it takes a few days to check out, but you go Monday morning.’” This was Saturday.

“Louisville is a good place to grow up and a good place to get away from,” Hunter said about leaving the womb of his hometown. It had prepared him for the outside world, armed him against oncoming storms, but now there was no reason to stay. He would take with him complex feelings of loss and abandonment, the anger and after-effects that would impact on his future life and friendships. For much of his writing in years to come, he would search for the death of the American Dream, perhaps never quite realizing that it was right in front of him all along, deep in his psyche, back there in his childhood.

“I look back on my youth with great fondness,” Hunter wrote in Kingdom of Fear, “but I would not recommend it as a working model for others. I was lucky to survive it at all.”

For anyone who knew Hunter at that time – his family, his friends, teachers, judges and, yes, Mr. Dotson, his “officious creep” of a probation officer – if they thought the Air Force would be the making of Hunter Stockton Thompson, they were in for a rude awakening.

Words by Leon Horton

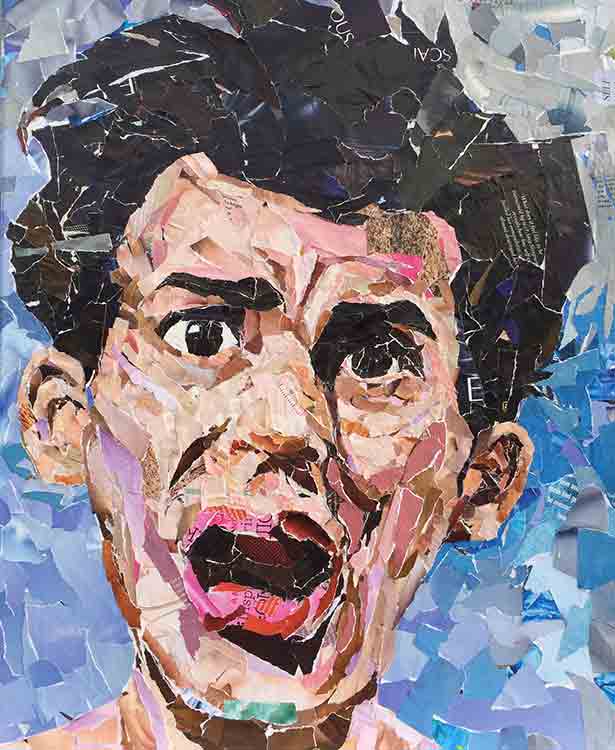

Artwork by Mark Fisher

About the author

Leon Horton is a cultural journalist and humorist. After gaining his masters from the University of Salford, he lost the will to live working as a court reporter (wouldn’t you?), drank himself into a corner writing upbeat “isn’t everything marvellous” crap for local magazines, and enjoyed a failed stint as the editor of Old Trafford News.

His writing has been described as “not quite what we’re looking for” and is published by Beat Scene, International Times, Beatdom, Literary Heist, Empty Mirror and Erotic Review. In January 2019, he became a member of the European Beat Studies Network.

When he’s not barking at the moon or up the wrong trouser leg, Leon can be found blogging Under the Counterculture at www.leonhorton.wordpress.com